![]()

Part 1

The Tomb Chapel

of Menna (TT 69)

![]()

Chapter 1

The Tomb of Menna and Its Owner

Melinda Hartwig

Previous work, construction,

and placement of the tomb

Cut into the cliffs or desert valley floor, Eighteenth Dynasty Theban tombs were composed of three levels: the upper level, or the chapel superstructure, which included the façade wall; a middle level composed of a walled forecourt leading to a rock-cut chapel; and a lower level made up of the subterranean burial complex. Each level served a purpose for the eternal life of the deceased: the upper façade related to his or her place within the celestial cycle, the middle-level chapel served as the site for the celebration of the tomb owner’s cult, and the lower-level tomb protected the owner’s body within the Osirian realm. Often the forecourt was sunk into the ground in order to gain the necessary height for the façade, and it was accessed by a ramp or stairway. Ideally, the forecourt was rectangular and opened to the east with the chapel façade to its west, creating a symbolic passage from the land of the living to the land of the dead in the ‘beautiful west.’ The façade was often crowned by a torus molding with a cavetto cornice and several rows of frieze cones set into the superstructure, each stamped with the name and titles of the deceased and his wife, as well as prayers and other dedications. Often, a niche was cut above the entrance to the chapel and housed a stelophorous statue of a kneeling man holding a stela inscribed with a hymn to the sun. The chapel was entered from the forecourt, through an entrance that was sometimes closed by a wooden door, which was easily opened for chapel ceremonies, celebrations, and other visits.

The lower-level burial complex was composed of one or more vertical shafts and/or sloping passages that were cut into the floor of the chapel or forecourt, each leading to single or multiple burial chambers below.1 The burial chamber held the coffin with the mummy and other funerary objects. Once the body and funerary goods were deposited in the burial chamber, the doorway was blocked by a wall of mud brick or stone slabs, and, if accessed by a vertical shaft, the shaft was filled in with stone or sand. The burial chamber could be used or reused for new burials over a period of several generations before it was abandoned.2 Often, the burial chamber was not decorated, although there are exceptions.3

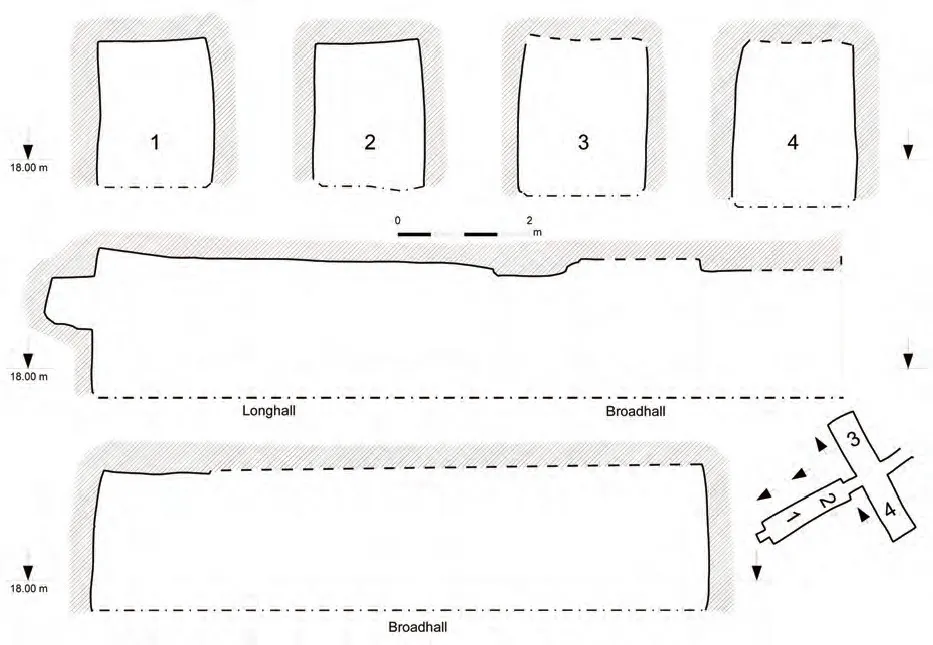

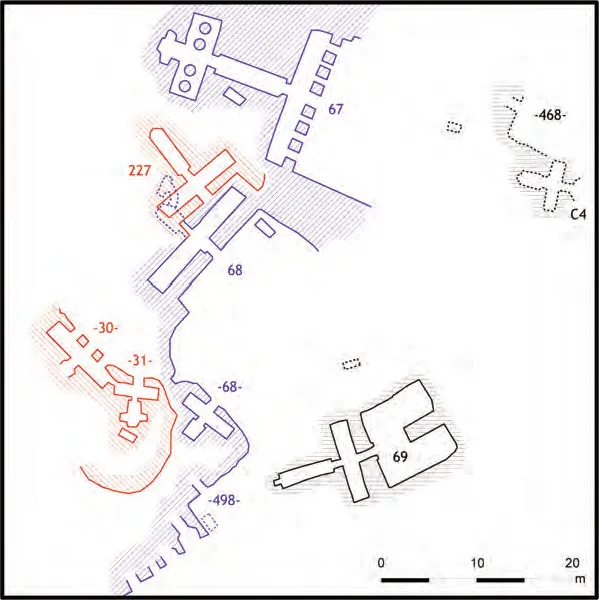

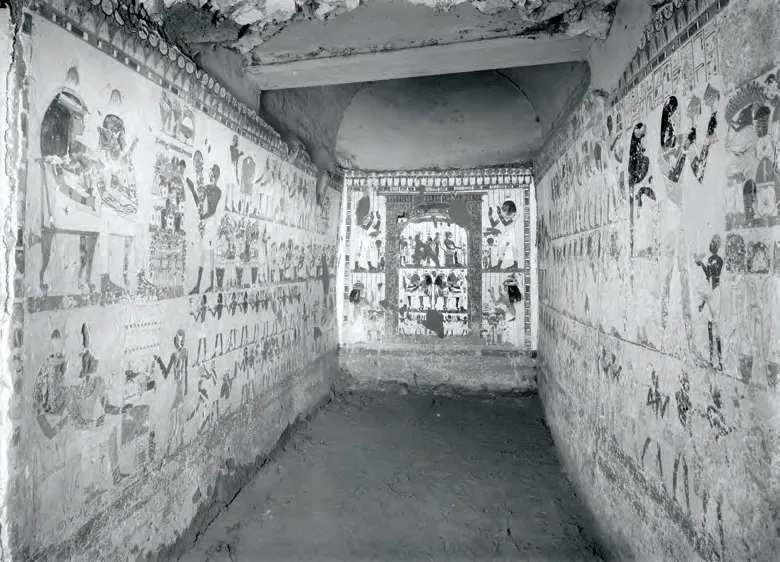

The tomb of Menna (TT 69) is, in many ways, an ideal Theban tomb structure. It is situated in a slightly sunken, enclosed forecourt. The plan of the tomb chapel is in the form of an inverted ‘T’ composed of a broad transverse hall and a long inner hall with a shrine at the end (Figs. 1.1, 1.2). Cut into the rock of the upper enclosure of Sheikh Abd al-Qurna, TT 69 lies adjacent to the tomb of the ‘high priest of Amun,’ Mery-Ptah (TT 68), which lies above TT 69 to the northwest; tomb C4 belonging to Mery-Ma’at, a ‘Wab-priest of Ma’at,’ is situated slightly to the northeast; and the tomb of Nakht (TT 52), an ‘hour-watcher of Amun,’ below the hill to the southeast (Fig. 1.3).4

The tomb of Menna has never been scientifically published. It was originally discovered by Gaston Maspero in 1886 and cleared by Robert Mond in 1903–1904 for the Antiquities Service.5 At the time Mond began the clearance, the tomb was already known by the local population, and to visiting Europeans through guidebooks. Since, the majority of the decorative program in the chapel has been documented, beginning with Colin Campbell, who did facsimile paintings of the decoration in 1910,6 and most recently, Mahmoud Maher-Taha in 2002.7 On the other hand, the textual program has never been fully examined.8

Figure 1.1: Ground plan of the tomb chapel of Menna (TT 69).

Figure 1.2: Tomb chapel of Menna sections.

Figure 1.3: TT 69 and surrounding tombs, Sheikh Abd al-Qurna.

Most of what is known of the original structure comes from Robert Mond’s clearance of the tomb for the Antiquities Service in 1903–1904. Mond noted that the courtyard of TT 69 was accessed by mud-brick steps and surrounded by a wall. Today, the courtyard sinks roughly 80 cm below the floor of the necropolis, and is accessed by a modern stone ramp (Fig. 0.1). Originally, the entrance to the chapel was framed by two inscribed doorjambs with an unpainted limeplaster lintel, all of which no longer remain.9 The modern entrance today is constructed of concrete.

Figure 1.4: Right exterior entrance-wall of the tomb chapel, covered with three layers of brown mud plaster with limestone chips and a layer of gypsum plaster. Remains of the pharaonic mud-brick wall can be seen to the far right. The Theban limestone dips appreciably to the far-right corner of the forecourt where the inner ceiling collapsed.

The walls adjacent to the entrance are composed of a mixture of ancient and modern mud brick. The wall to the immediate right is covered with three layers of light-brown marl plaster with chips of limestone and the remains of a layer of beige gypsum plaster (Fig 1.4). Above, the very brittle native Theban limestone dips appreciably to the far-right corner of the forecourt. Behind this wall, inside the chapel, Ernest Mackay noted that the ceiling above the right wing and part of the left wing of the Broad Hall had collapsed, leaving only 127 cm of decorated ceiling above the left broad-hall wing.10 Three wooden beams, and later four light iron girders, were set up to support the ceiling.11 A series of photographs taken by Harry Burton for the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition clearly depicts an arched ceiling composed of mud plaster at the far right of the Broad Hall, and a beam running between the lateral walls as a support for the roof (Fig. 1.5). As discussed in chapter 4, the Long Hall was secured by a similar arrangement of wooden beams.

Figure 1.5: The old wooden bracing system in place around 1920–21 on the right wing of the Broad Hall Ceiling (BHC). Photography by the Egyptian Expedition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Inside the Broad Hall on the right-hand side, nearest the entrance (BHNR), remains of a color band can be seen that bordered the initial entrance door of the tomb, approximately 150 cm from the edge of the modern entrance. (Compare Figure 2.8a and Figure 2.8b.) At some point, the Broad Hall of the tomb was extended to the southeast and a new entrance door was cut that roughly conforms to the modern door today. The original door was filled in with a combination of limestone chips and muna (a mixture of mud and chopped straw). Based on the similar pigment recipes from the first and second phases of decoration ascertained by X-ray fluorescence, the movement of the entrance was contemporary with the original decoration of the tomb. The artists did not change the original scenes and texts (rendered in blue line), but simply moved them to the right to coincide with the new door.12

A two-by-two-meter square was cleared in the forecourt floor directly before the outer wall, positioned to correspond with the earlier color band inside the chapel on BHNR, to see if the remains of the original door could be ascertained (Fig. 1.6). This earlier door is also noted by a dotted line on Figure 1.1. The inset shows the remains of the original entrance plaster that was part of the raised doorstep that led into the tomb.13

Figure 1.6: Remains of entrance step to TT 69, composed of plaster underneath the muna–limestone fill. The exposed doorstep is 57 cm long x 4.5 cm high. It occurs approximately 143 cm from the right edge of the modern door jamb.

The question remains: why was it necessary to move the door? One reason could be the bad quality of the rock. When constructing a Theban tomb, a passage was hewn into the rock that conformed to the height (and perhaps length) of the structure. Red lines indicated the central axis of the tomb (and at right angles, the transverse hall, if cutting a T-shape tomb).14 Once the basic tomb was cut, the plasterers and painters would go to work. If one looks carefully at the right wing of the Broad Hall in the chapel, the bottom corners of the shrine wall were not straightened, due to the quality of the rock. The stability of the ceiling over the right wing may also have been a concern to the workmen.

Another reason may be the existence of another tomb to the right of TT 69 that was discovered or known when Menna’s tomb chapel was under construction, but its exact coordinates are lost today. The debris mounds and hillocks between TT 69 and the forecourt of TT 68 remain unexcavated and could yield a previously discovered or unknown burial. The dotted square conforms to an existing shaft and may point the way to where the tomb is to be found (see Fig.1.3). Whatever the reason, the artists quickly discovered the error and extended the tomb to the left, moving the decoration and texts with it.

Moving back outside to the forecourt and to the walls of the west and east elevation, the layer of Theban limestone is capped with a modern stone wall that levels off roughly two feet above the modern doorway (indicated gray on Fig.1.1). At the top of the stone wall, a modern roof covered with a layer of scree (small loose stones) stretches about 6 m back from the tomb’s entrance doorway to the beginning of the Long Hall (see Fig. 0.1). A higher modern stone wall rises above the roof and forms a semicircle that steps down on both sides, ending at the level of the necropolis floor to the southeast, and turning slightly toward the north on the northwest. Two stone wings extend out from this semicircular wall, leaving an opening of roughly 40 cm to access the stone ramp that leads into the forecourt.

The south elevation of the forecourt is largely reconstructed out of horizontal layers of modern stone (Figs. 1.7a, 1.7b). Horizontal layers (up to one meter) of the pharaonic gray mud brick are preserved at the far-left edge, and a few bricks remain in the center and to the far right. These original bricks can be distinguished from the modern mud bricks by their gray color and dimensions (31–32 x 13.5–14.5 x 9.5 cm).15 In the middle of the western elevation there are remains of the original pharaonic stone wall, covered in areas with a beige marl plaster with limestone chips to even out the surface.

The east elevation of the court is composed of 3.1 m of modern mud brick from the right edge to the center of the wall at a height of 2 m. The original entry jambs to tomb –312-16 can be seen made of mud brick covered with beige marl mortar with chips of limestone. The remaining 3.3 m of wall is the rock face. In the northern elevation, the two small wings to either side of the ramp to the forecourt were originally composed of two courses of mud brick in 1903–1904, according to Mond. A few bricks remain on the northwestern side. Today, they are constructed of the same type of modern stone used for the retaining walls around Menna. Below the wings, areas of the rock face are coated with a layer of marl plaster, with and without limestone chips.

Although the various modern additions to the forecourt and enclosure wall of TT 69 make it hard to reconstruct its original arrangement, a few suggestions are offered here. The façade and wing walls were worked out vertically from the rock and the forecourt was cut about 0.8–1 m into the limestone floor. The brittle limestone rock face of these walls was covered with a beige marl plaster, reinforced with straw and limestone chips of varying sizes, and painted with a light brown-beige wash to create an even surface. Above the limestone, mud-brick walls were constructed to even out the irregular height of the rock face. The height of the original ...