![]()

IV

Sector-Specific Issues

![]()

16

Urban Policy Effects on Carbon Mitigation

Matthew E. Kahn*

16.1 Introduction

Suppose that a household was choosing between living in Houston or San Francisco. In each city, what would this household’s annual carbon footprint be? Glaeser and Kahn (2010) estimate that a standardized household would create 12.5 extra tons of carbon dioxide per year if it moved to Houston rather than moving to San Francisco. In Houston, the same household drives more, lives in a bigger home, uses more residential electricity—electricity that is generated by power plants with a higher carbon emissions factor. Using data from the year 2000 across sixty-four major metropolitan areas, Glaeser and Kahn (2010) document that Pittsburgh is the city with the median residential household footprint of 28.3 tons of carbon dioxide per year, while San Francisco is the third “greenest” metropolitan area, and Houston is the third “brownest” metro area. This cross-sectional descriptive work creates a benchmark for comparing cities’ household carbon emissions from transportation, electricity consumption, and home heating, at a point in time and tracking city trends over time.

Given that greenhouse gas emissions are a global externality, households are unlikely to internalize the carbon consequences of moving to a city such as Houston rather than San Francisco. Why is San Francisco “greener” than Houston? San Francisco is blessed with a temperate climate. Northern California’s electric utilities emit less greenhouse gas emissions than their Texas counterparts. Due to its amenities, land prices are higher in San Francisco, and its residents live in smaller homes than their Houston counterparts. Land prices are highest downtown, and this encourages economy activity to be highly compact. Such population density in San Francisco encourages households to live a walking, “new urbanist” life. This low-carbon lifestyle would be rare in sprawling Houston.

Over the last 100 years, people and jobs have been moving away from center cities. The average person who lived in a metropolitan area lived 9.8 miles from the city center in 1970, and this distance grew to 13.2 miles by the year 2000. While privately beneficial, this trend has helped to exacerbate the challenge of mitigating greenhouse gas production. Suburbanites drive more and live in larger homes that require more heating and cooling than their urban counterparts.

This chapter uses three different data sets to document that households who live in center cities drive less, use public transit more, and consume less electricity than observationally similar households who live in the suburbs. This center city/suburban differential is largest in the Northeast’s monocentric cities such as New York City. Given that households choose where to live, this differential could be caused by both residential self-selection and a true causal “treatment effect” of urban living. If these correlations are due to a treatment effect, then any pro-center city policy, such as policies directed toward reducing inner-city crime, is likely to reduce a metropolitan area’s carbon footprint.

16.2 Urban Transportation

16.2.1 Miles Driven as a Function of Urban Form

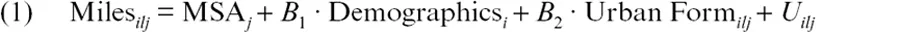

The Department of Transportation has recently released the 2009 National Household Transportation Survey (NHTS) micro data.1 This micro data set is distinctive because it reports household vehicle mileage for a large representative sample of households. Using a special version of the data set that has census tract identifiers, I restrict the sample to households living within thirty-five miles of a major city center. For each household, I observe which metropolitan area it lives in, its distance to the city center, and its distance to the closest rail transit station using data from Baum-Snow and Kahn (2005). I estimate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for household i living in census tract 1 in metropolitan area j using observations on over 92,000 households based on equation (1):

In this regression, the dependent variable is the household’s total miles driven in the last year. I trim the dependent variable and set the dependent variable equal to the 99th percentile of the empirical distribution for observations in the top percentile. In table 16.1 columns (1) and (2) are identical except that the results in column (2) include metropolitan area fixed effects. In these regressions, I control for household income, the number of people in the household, and the age of the head of the household. Controlling for these demographic factors, my primary interest is to measure the association between a household’s total miles driving and its location within the metropolitan area, the population density where it lives, and where it lives within one mile of a rail transit line. The results are roughly similar wi...