Abstract

Problematic use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs is the leading cause of preventable deaths and disability in the United States. As drugs impact every sector of society, no other field of biobehavioral science so closely contacts and contends with political, policy, ethical, moral, legal, public safety, and economic issues, nationally and internationally. Biobehavioral research has outsized potential for shaping public views, policies, and programs, but its impact has been limited by discontinuities between research, education, implementation, and practice. This narrative provides an overview of the history of drug use and regulatory responses, the impact of drugs on individuals and society, risk factors for use and populations at risk, an overview of how drugs affect the brain at micro- and macrolevels, policy implications, and policy recommendations. It serves as a foundation for other chapters in the book that address specific drugs. My perspective is forged by an odyssey through three terrains—scientific research, public education, and government service.

1 Introduction

Humans are explorers of territory, new ideas, social contacts, mates, and sources of food. Successful exploration produced rewards, reinforced behaviors, and enhanced survival. Over millennia, our ancestors explored plants as food sources and serendipitously discovered that certain plants engendered unique rewarding stimuli. Some ingested phytochemicals were mildly arousing (e.g. nicotine, caffeine), others enhanced mood or altered perception, reduced dysphoria and pain, or intoxicated with mild or intense euphoria (alcohol, marijuana, hallucinogens, opiates, cocaine). Over the past two centuries, consumption of these substances expanded exponentially. Isolation from source materials, purification, chemical modification, delivery by chemical mechanisms or devices for maximum effect, and global marketing contributed to this expansion. Modern chemistry, production, and marketing methods produced an array of consumed drugs capable of generating hedonic signals that usurped motivational and volitional control of behaviors essential for survival. Drug use (tobacco, alcohol, other drugs) now accounts for nearly 25% of deaths annually in the United States. Death is not the sole peril. We have witnessed an unprecedented level of adverse biological, behavioral, medical, and social consequences.

1.1 Early Origins

The use of psychoactive drugs for religious, ritualistic, and medical purposes is an ancient practice, documented in texts, evidenced in artifacts (e.g. seeds, pipes), in trace chemical signatures, and artistic and sculptural images. References to excessive alcohol consumption are found in ancient, historical documents and literary prose (e.g. the historian Josephus, and William Shakespeare). Opiates are implicated in this quote from Homer (ninth century B.C.): “presently she cast a drug into the wine of which they drank to lull all pain and anger and bring forgetfulness of every sorrow…” Opiates were used for medicinal or psychoactive purposes, as they migrated from Sumeria to India, China and Western Europe (Brownstein, 1993). By the sixteenth century, manuscripts describing opioid drug abuse and tolerance were published in various countries, a consequence greatly accelerated by the isolation of morphine from the opium poppy in 1803 (Brownstein, 1993). Marijuana is another ancient drug, used by Eastern cultures for medical and psychoactive purposes. Physical evidence of its use was found in ashes beside a skeleton of a 14-year-old girl, apparently in the midst of a failed breech birth (Zias et al., 1993). Cryptic mentions of mystifying drug effects in ancient texts (Dannaway et al., 2006; Dannaway, 2010), or religious prohibitions are scattered in various sources, but there is scant evidence that ancient drug use was as extensive or propagated the same public health, welfare, safety concerns, and consequences or responses, as in modern times.

1.2 Modern Era

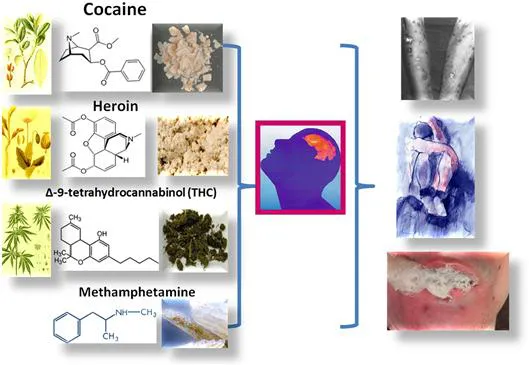

The past two centuries have witnessed an exponential rise in drug use and a corresponding increase in associated consequences. The increase has been fueled by modernization: (1) the discovery and cross-cultural propagation of psychoactive drugs by explorers of new continents; (2) the advent of organic chemistry, which enabled isolation of pure, potent drugs from plants (e.g. cocaine, morphine) and de novo synthesis of new drugs (e.g. oxycodone, methamphetamine, amphetamine, cannabicyclohexanol) guided by structures of isolated phytochemicals (morphine, ephedrine, THC or Δ-9-tetrahydrocannbinol); (3) the development of modern drug delivery systems, the needle/syringe, the cigarette-rolling machine, and synthetic salt forms of drugs that enable efficient drug delivery systems; (4) the advent of sophisticated agricultural and purification methods increased drug concentrations in plants and improved crop yields; (5) modern capitalism increased prosperity and expendable income across classes. Expansion of user markets raised the profitability for manufacturing and sales of drugs; (6) sophisticated global marketing exploited modern, efficient communication and transportation systems; (7) cultural shifts eroded parental/family oversight at earlier stages of development; (8) drug use was normalized by cultural icons, media, and internet sites; (9) drug use was promoted by wealthy individuals for cryptic reasons, by underwriting state ballot and legislative initiatives to promote drug normalization, and by profit-seeking industries using advertising targeted to youth. The net effect was to make highly potent drugs widely available. A new enterprise, distribution of simple chemicals isolated and purified from plants, was born (Figure 1). The nineteenth century came to a close, with a cocaine and morphine epidemic in the United States, and a severe opium epidemic, especially in Asia. The twentieth century closed with global marketing and consumption of an array of phytochemicals and synthetic, “designer” drugs. The trajectory of the twenty-first century will be driven by national and international laws, regulations, shaped by biomedical science and informed public opinion.

Figure 1 The biology of addiction. A simple ingested chemical, isolated from a plant and of molecular weight less than 1000, can profoundly affect the brain and body. On top right is a photo of “skin popping”, a method of injection of cocaine under the skin that leaves lesions. The bottom right is a photo of a person with respiratory depression, resulting from a heroin overdose.

In the late nineteenth century, drugs were advertised, freely available, unregulated in patent medicines, sold freely in drugstores, dissolved in popular drinks (colas and wines), as tonics, elixirs, and remedies. The major drugs at that time, heroin, morphine, cocaine, and marijuana, were marketed without restraint and had vocal or covert supporters, including high-profile physicians, Sigmund Freud and William Halsted, who succumbed to severe addiction (Musto, 1968, 2002; White, 1998; Musto et al., 2002; Gay et al., 1975; Cohen, 1975).

Problems with cocaine were evident from the beginning. By the turn of the twentieth century, 200,000 people are estimated to have been addicted to drugs in the United States alone. Increased availability, rapid rates of brain entry, distribution of multiple drugs, and initiation by younger populations more susceptible to addiction created an unfettered market for drugs.

1.3 Advent of Regulations and Laws

The adverse consequences aroused attention and legislative responses from physicians, national governments, and international organizations. As the medical historian David Musto stated “from repeated observation of the damage to acquaintances and society”, awakened national and international governments to counteract these trends with regulatory, taxation and laws. In 1875 opium dens were outlawed in San Francisco. In 1906, the federal government passed the Pure Food and Drugs Act, a law a quarter-century in the making, that prohibited interstate commerce in adulterated and misbranded food and drugs and required accurate labeling of patent medicines containing opium and other drugs. The modern regulatory functions of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began with the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act, which provided basic elements of protection that consumers had not known before that time. Despite rapid metamorphic changes in our medical, cultural, economic, and political institutions over the past century, the core public health mission of the FDA retains a protective barrier against unsound claims and unsafe, ineffective drugs.

The 1906 legislation was extended by passage of the Harrison Act in 1914 forbidding the sale of narcotics or cocaine, except by licensed physicians. Regulatory mechanisms marched in tandem with newly emerging drugs, restricting harm to individuals by restricting access to drugs. Prior to the 1960s, Americans did not see drug use as an acceptable behavior, or an inevitable fact of life. Tolerance of drug use led to a dramatic rise in crime between 1960s and early 1990s, and the landscape of America was altered forever, (DEA). Consequently, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created in 1973 by Executive Order to establish a single unified command over legal control of drugs and address America’s growing drug problem. Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act to consolidate and replace, by then, more than 50 pieces of drug legislation. It established a single system of control for both narcotic and psychotropic drugs for the first time in the U.S. history (DEA).

Since the creation of the DEA, drug policy has been debated as choices between activists for free access to drugs and advocates for restrictive policies (Dupont et al., 2011). Activists view regulations as a restraint on their right to freely pursue “victimless” drug-induced pleasure, expansion of consciousness and of potential, self-medication, and profit. They are buoyed by narrow views that claim few people become addicted and that some addicts are productive. For example, Nikki Sixx documents in his book “The Heroin Diaries: a Year in the Life of a Shattered Rock Star”, his ability, albeit limited, to perform during a severe addiction. Significantly, drug use is highest among 15–25 year olds, the “age of invulnerability”. Advocates of stringent policies view drug use issues through a prism of human health, welfare, social, and safety concerns. The resistance to drugs and a shift in perceptions takes years to penetrate the public opinion, when drug use becomes viewed as reducing natural potential, and the consequences of drugs in family members, schools, and the workplace begin to take a toll (Musto, 1995). The counterclaims to restrictive legal and social containment of drug commerce and consumption are based on drug-seeking and use as historical, normative, acceptable, inevitable, a rite of passage, an expression of personal liberty, an extension of natural potential, and a victimless social activity. Some advocates acknowledge the evidence that drugs can produce adverse consequences to individual users (overdose and death, HIV-AIDS, dehydration), and focus on reducing “drug-associated harm”. Needle exchange programs (designated syringe exchange program by advocates to substitute the pejorative delivery system “needle” with a container designation “syringe”), provision of water bottles at ecstasy-infused “rave” parties, and advocating for over-the-counter naloxone for opioid overdose crises, are practical solutions to “harm reduction”. Reducing supply or demand for drugs and prevention and intervention program are not emphasized in this movement.

From my perspective, “harm reduction” is incompatible with strong evidence fr...