eBook - ePub

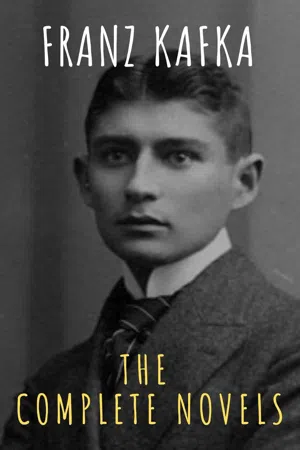

Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels

Franz Kafka, The griffin classics

This is a test

- 539 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels

Franz Kafka, The griffin classics

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Content: UnhappinessThe JudgmentBefore the LawThe MetamorphosisA Report to an AcademyJackals and ArabsA Country DoctorIn the Penal ColonyA Hunger ArtistThe TrialThe CastleAmerikaA Little FableThe Great Wall of ChinaThe Hunter GracchusThe Burrow

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels par Franz Kafka, The griffin classics en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Literature et German Literary Criticism. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

LiteratureSous-sujet

German Literary CriticismThe Castle

First published: 1926

a novel

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16 — Amalia’s Secret

Chapter 17 — Amalia’s Punishment

Chapter 18 — Petitions

Chapter 19 — Olga’s Plans

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 1

It was late in the evening when K. arrived. The village was deep in snow. The Castle hill was hidden, veiled in mist and darkness, nor was there even a glimmer of light to show that a castle was there. On the wooden bridge leading from the main road to the village K. stood for a long time gazing into the illusory emptiness above him. Then he went on to find quarters for the night. The inn was still awake, and although the landlord could not provide a room and was upset by such a late and unexpected arrival, he was willing to let K. sleep on a bag of straw in the parlour. K. accepted the offer. Some peasants were still sitting over their beer, but he did not want to talk, and after himself fetching the bag of straw from the attic, lay down beside the stove. It was a warm corner, the peasants were quiet, and letting his weary eyes stray over them he soon fell asleep. But very shortly he was awakened. A young man dressed like a townsman, with the face of an actor, his eyes narrow and his eyebrows strongly marked, was standing beside him along with the landlord. The peasants were still in the room, and a few had turned their chairs round so as to see and hear better. The young man apologized very courteously for having awakened K., introducing himself as the son of the Castellan, and then said:

“This village belongs to the Castle, and whoever lives here or passes the night here does so in a manner of speaking in the Castle itself. Nobody may do that without the Count’s permission. But you have no such permit, or at least you have produced none.”

K. had half raised himself and now, smoothing down his hair and looking up at the two men, he said:

“What village is this I have wandered into? Is there a castle here?”

“Most certainly,” replied the young man slowly, while here and there a head was shaken over K.’s remark, “the castle of my lord the Count West-west.”

“And must one have a permit to sleep here?” asked K., as if he wished to assure himself that what he had heard was not a dream.

“One must have a permit,” was the reply, and there was an ironical contempt for K. in the young man’s gesture as he stretched out his arm and appealed to the others, “Or must one not have a permit?”

“Well, then, I’ll have to go and get one,” said K. yawning and pushing his blanket away as if to rise up.

“And from whom, pray?” asked the young man.

“From the Count,” said K., “that’s the only thing to be done.”

“A permit from the Count in the middle of the night!” cried the young man, stepping back a pace.

“Is that impossible?” inquired K. coolly. “Then why did you waken me?”

At this the young man flew into a passion.

“None of your guttersnipe manners!” he cried, “I insist on respect for the Count’s authority I I woke you up to inform you that you must quit the Count’s territory at once.”

“Enough of this fooling,” said K. in a markedly quiet voice, laying himself down again and pulling up the blanket.

“You’re going a little too far, my good fellow, and I’ll have something to say tomorrow about your conduct. The landlord here and those other gentlemen will bear me out if necessary. Let me tell you that I am the Land Surveyor whom the Count is expecting. My assistants are coming on tomorrow in a carriage with the apparatus. I did not want to miss the chance of a walk through the snow, but unfortunately lost my way several times and so arrived very late. That it was too late to present myself at the Castle I knew very well before you saw fit to inform me. That is why I have made shift with this bed for the night, where, to put it mildly, you have had the discourtesy to disturb me. That is all I have to say. Good night, gentlemen.”

And K. turned over on his side towards the stove.

“Land Surveyor?” he heard the hesitating question behind his back, and then there was a general silence. But the young man soon recovered his assurance, and lowering his voice, sufficiently to appear considerate of K.’s sleep while yet speaking loud enough to be clearly heard, said to the landlord:

“I’ll ring up and inquire.”

So there was a telephone in this village inn? They had everything up to the mark. The particular instance surprised K., but on the whole he had really expected it. It appeared that the telephone was placed almost over his head and in his drowsy condition he had overlooked it. If the young man must needs telephone he could not, even with the best intentions, avoid disturbing K., the only question was whether K. would let him do so; he decided to allow it. In that case, however, there was no sense in pretending to sleep, and so he turned on his back again. He could see the peasants putting their heads together, the arrival of a Land Surveyor was no small event.

The door into the kitchen had been opened, and blocking the whole doorway stood the imposing figure of the landlady, to whom the landlord was advancing on tiptoe in order to tell her what was happening. And now the conversation began on the telephone. The Castellan was asleep, but an under-castellan, one of the under-castellans, a certain Herr Fritz, was available. The young man, announcing himself as Schwarzer, reported that he had found K., a disreputable-looking man in the thirties, sleeping calmly on a bag of straw with a minute rucksack for pillow and a knotty stick within reach. He had naturally suspected the fellow, and as the landlord had obviously neglected his duty he, Schwarzer, had felt bound to investigate the matter. He had roused the man, questioned him, and duly warned him off the Count’s territory, all of which K. had taken with an ill grace, perhaps with some justification, as it eventually turned out, for he claimed to be a Land Surveyor engaged by the Count. Of course, to say the least of it, that was a statement which required official confirmation, and so Schwarzer begged Herr Fritz to inquire in the Central Bureau if a Land Surveyor were really expected, and to telephone the answer at once. Then there was silence while Fritz was making inquiries up there and the young man was waiting for the answer.

K. did not change his position, did not even once turn round, seemed quite indifferent and stared into space. Schwarzer’s report, in its combination of malice and prudence, gave him an idea of the measure of diplomacy in which even underlings in the Castle like Schwarzer were versed. Nor were they remiss in industry, the Central Office had a night service. And apparently answered questions quickly, too, for Fritz was already ringing. His reply seemed brief enough, for Schwarzer hung up the receiver immediately, crying angrily:

“Just what I said! Not a trace of a Land Surveyor. A common, lying tramp, and probably worse.”

For a moment K. thought that all of them, Schwarzer, the peasants, the landlord and the landlady, were going to fall upon him in a body, and to escape at least the first shock of their assault he crawled right underneath the blanket. But the telephone rang again, and with a special insistence, it seemed to K. Slowly he put out his head.

Although it was improbable that this message also concerned K., they all stopped short and Schwarzer took up the receiver once more. He listened to a fairly long statement, and then said in a low voice: “A mistake, is it? I’m sorry to hear that. The head of the department himself said so?

Very queer, very queer. How am I to explain it all to the Land Surveyor?”

K. pricked up his ears. So the Castle had recognized him as the Land Surveyor. That was unpropitious for him, on the one hand, for it meant that the Castle was well informed about him, had estimated all the probable chances, and was taking up the challenge with a smile. On the other hand, however, it was quite propitious, for if his interpretation were right they had underestimated his strength, and he would have more freedom of action than he had dared to hope. And if they expected to cow him by their lofty superiority in recognizing him as Land Surveyor, they were mistaken; it made his skin prickle a little, that was all. He waved off Schwarzer who was timidly approaching him, and refused an urgent invitation to transfer himself into the landlord’s own room; he only accepted a warm drink from the landlord and from the landlady a basin to wash in, a piece of soap, and a towel. He did not even have to ask that the room should be cleared, for all the men flocked out with averted faces lest he should recognize them again next day. The lamp was blown out, and he was left in peace at last.

He slept deeply until morning, scarcely disturbed by rats scuttling past once or twice. After breakfast, which, according to his host, was to be paid for by the Castle, together with all the other expenses of his board and lodging, he prepared to go out immediately into the village. But since the landlord, to whom he had been very curt because of his behaviour the preceding night, kept circling around him in dumb entreaty, he took pity on the man and asked him to sit down for a while.

“I haven’t met the Count yet,” said K., “but he pays well for good work, doesn’t he? When a man like me travels so far from home he wants to go back with something in his pockets.”

“There’s no need for the gentleman to worry about that kind of thing; nobody complains of being badly paid.”

“Well,” said K.,” I’m not one of your timid people, and can give a piece of my mind even to a Count, but of course it’s much better to have everything settled up without any trouble.”

The landlord sat opposite K. on the rim of the window-ledge, not daring to take a more comfortable seat, and kept on gazing at K. with an anxious look in his large brown eyes. He had thrust his company on K. at Erst, but now it seemed that he was eager to escape. Was he afraid of being cross-questioned about the Count? Was he afraid of some indiscretion on the part of the “gentleman” whom he took K. to be? K. must divert his attention. He looked at the clock, and said:

“My assistants should be arriving soon. Will you be able to put them up here?”

“Certainly, sir,” he said, “but won’t they be staying with you up at the Castle?”

Was the landlord so willing, then, to give up prospective customers, and K. in particular, whom he so unconditionally transferred to the Castle?

“That’s not at all certain yet,” said K. “I must first find out what work I am expected to do. If I have to work down here, for instance, it would be more sensible to lodge down here. I’m afraid, too, that the life at the Castle wouldn’t suit me. I like to be my own master.”

“You don’t know the Castle,” said the landlord quietly.

“Of course,” replied K., “one shouldn’t judge prematurely. All that I know at present about the Castle is that the people there know how to choose a good Land Surveyor. Perhaps it has other attractions as well.”

And he stood up in order to rid the landlord of his presence, since the man was biting his lip uneasily. His confidence was not to be lightly won. As K. was going out he noticed a dark portrait in a dim frame on the wall. He had already observed it from his couch by the stove, but from that distance he had not been able to distinguish any details and had thought that it was only a plain back to the frame. But it was a picture after all, as now appeared, the bust portrait of a man about fifty. His head was sunk so low upon his breast that his eyes were scarcely visible, and the weight of the high, heavy forehead and the strong hooked nose seemed to have borne the head down. Because of this pose the man’s full beard was pressed in at the chin and spread out farther down.

His left hand was buried in his luxuriant hair, but seemed incapable of supporting the head.

“Who is that?” asked K., “the Count?”

He was standing before the portrait and did not look round at the landlord.

“No,” said the latter, “the Castellan.”

“A handsome castellan, indeed,” said K., “a pity that he had such an ill-bred son.”

“No, no,” said the landlord, drawing K. a little towards him and whispering in his ear, “Schwarzer exaggerated yesterday, his father is only an under-castellan, and one of the lowest, too.”

At that moment the landlord struck K. as a very child.

“The villain!” said K. with a laugh, but the landlord instead of laughing said, “Even his father is powerful.”

“Get along with you,” said K., “you think everyone powerful. Me too, perhaps?”

“No,” he replied, timidly yet seriously, “I don’t think you powerful.”

“You’re a keen observer,” said K., “for between you and me I’m not really powerful. And consequently I suppose I have no less respect for the powerful than you have, only I’m not so honest as you and am not always willing to acknowledge it.”

And K. gave the landlord a tap on the cheek to hearten him and awaken his friendliness. It made him smile a little. He was actually young, with that soft and almost beardless face of his; how had he come to have that massive, elderly wife, who could be seen through a small window bustling about the kitchen with her elbows sticking out? K. did not want to force his confidence any further, however, nor to scare away the smile he had at last evoked. So he only signed to him to open the door, and went out into the brilliant winter morning.

Now, he could see the Castle above him clearly defined in the glittering air, its outline made still more definite by the moulding of snow covering it in a thin layer. There seemed to be much less snow up there on the hill than down in the village, where K. found progress as laborious as on the main road the previous day. Here the heavy snowdrifts reached right up to the cottage windows and began again on the low roofs, but up on the hill everything soared light and free into the air, or at least so it appeared from down below. On the whole this distant prospect of the Castle satisfied K.’s expectations. It was neither an old stronghold nor a new mansion, but a rambling pile consisting of innumerable small buildings closely packed together and of one or two storeys; if K. had not known that it was a castle he might have taken it for a little town. There was only one tower as far as he could see, whether it belonged to a dwelling-house or a church he could not determine. Swarms of crows were circling round it. With his eyes fixed on the Castle K. went on farther, thinking of nothing else at all. But on approaching it he was disappointed in the Castle; it was after all only a wretched-looking town, a huddle of village houses, whose sole merit, if any, lay in being built of stone, but the plaster had long since flaked off and the stone seemed to be crumbling away. K. had a fleeting recollection of his native town. It was hardly inferior to this so-called Castle, and if it were merely a question of enjoying the view it was a pity to have come so far. K. would have done better to visit his native town again, which he had not seen for such a long time. And in his mind he compared the church tower at home with the tower above him. The church tower, firm in line, soaring unfalteringly to its tapering point, topped with red tiles and broad in the roof, an earthly building — what else can men build? — but with a loftier goal than the humble dwellinghouses, and a clearer meaning than the muddle of everyday life. The tower above him here-the only one visible-the tower of a house, as was now apparent, perhaps of the main building, was uniformly round, part of it graciously mantled with ivy, pierced by small windows that glittered in the sun, a somewhat maniacal glitter, and topped by what looked like an attic, with battlements that were irregular, broken, fumbling, as if designed by the trembling or careless hand of a child, clearly outlined against the blue. It was as if a melancholy-mad tenant who ought to have been kept locked in the topmost chamber of his house had burst through the roof and lifted himself up to the gaze of the world.

Again K. came to a stop, as if in standing still he had more power of judgement. But he was disturbed. Behind the village church where he had stopped-it was really only a chapel widened with barn-like additions so as to accommodate the parishioners — was the school.

A long, low building, combining remarkably a look of great age with a provincial appearance, it lay behind a fenced-in garden which was now a field of snow. The children were just coming out with their teacher. They thronged round him, all gazing up at him and chattering without a break so rapidly that K. could not follow what they said. The teacher, a small young man with narrow shoulders and a very upright carriage which yet did not make him ridiculous, had already fixed K. with his eyes from the distance, naturally enough, for apart from the school-children there was not another human being in sight. Being the stranger, K. made the first advance, especially as the other was an authoritative-looking little man, and said:

“Good morning, sir.”

As if by one accord the children fell silent, perhaps the master liked to have a sudden stillness as a preparation for his words.

“You are looking at the Castle?” he asked more gently than K. had expected, but with the inflexion that denoted disapproval of K.’s occupation.

“Yes,” said K. “I am a stranger here, I came to the village only last night.”

“You don’t like the Castle?” returned the teacher quickly.

“What?” countered K., a little taken aback, and repeated the question in a modified form. “Do I like the Castle? Why do you assume that I don’t like it?”

“Strangers never do,” said the teacher.

To avoid saying the wrong thing K. changed the subject and asked: “I suppose you know the Count?”

“No,” said the teacher turning away.

But K. would not be put off and asked again: “What, you don’t know the Count?”

“Why should I?” replied the teacher in a low tone, and added aloud in French: “Please remember that there are innocent children...

Table des matières

- Title Page

- Unhappiness

- The Judgment

- Before the Law

- The Metamorphosis

- A Report to an Academy

- Jackals and Arabs

- A Country Doctor

- In the Penal Colony

- A Hunger Artist

- The Trial

- The Castle

- Amerika

- A Little Fable

- The Great Wall of China

- The Hunter Gracchus

- The Burrow

Normes de citation pour Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels

APA 6 Citation

Kafka, F., & Classics, T. griffin. (2020). Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels ([edition unavailable]). The griffin classics. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1946471/franz-kafka-the-complete-novels-pdf (Original work published 2020)

Chicago Citation

Kafka, Franz, and The griffin Classics. (2020) 2020. Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels. [Edition unavailable]. The griffin classics. https://www.perlego.com/book/1946471/franz-kafka-the-complete-novels-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Kafka, F. and Classics, T. griffin (2020) Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels. [edition unavailable]. The griffin classics. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1946471/franz-kafka-the-complete-novels-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Kafka, Franz, and The griffin Classics. Franz Kafka: The Complete Novels. [edition unavailable]. The griffin classics, 2020. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.