From Clouds to the Brain

The Movement of Electricity in Medical Science

Celine Cherici

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

From Clouds to the Brain

The Movement of Electricity in Medical Science

Celine Cherici

À propos de ce livre

Based on research on the links between deep brain stimulation and its applications in the field of psychiatry, the history of techniques is of great importance in this book in order to understand the scope of the fields of application of electricity in brain sciences. The concepts of brain electricity, stimulation, measurement and therapy are further developed to identify lines of convergence, ruptures and conceptual perspectives for a materialistic understanding of human nature that emerged during the 18th century. In an epistemological posture, at the crossroads of the concepts of epistemes, as stated by Foucault, and phenomenotechnics, as conceived by Bachelard, the analyses focus on the technical content of the theories while inscribing them in the language and specificities of each era.

Foire aux questions

Informations

1

The Birth of an Electrical Culture: From Frankenstein to Hyde

- – “re” creating life: indeed, experiments on the bodies of convicts were adjacent to the theme of electricity as the driving force of life. Aldini and Cumming, by re-animating corpses, dramatized demonstrations, thus spreading the links between galvanism and vital properties;

- – control of behaviors: in the middle of the 19th Century, electrical medicine broke with the dualistic paradigm of the electrified automaton to locate, in the brain, the areas that would allow the control of behaviors through these therapies. This movement followed a more general shift from moral issues to psychiatric disorders.

1.1. “Re”creating life?

‘Then I shot him,’ he says ‘a few sparks from the tip of his nose, which made him stand up on his legs to complete his healing, I gave him a couple of fairly light jerks. All this work didn’t last six minutes when with the third shake the animal ran away, […]’. [BER 80, p. 55, author’s translation]1

The Ecole de Médecine de Paris (Paris Medical School) tried to subject asphyxiated animals to Galvanic action; in its research it set out to determine the action of this stimulant on the muscular organs. It has mainly experimented with rabbits and small guinea pigs. The state of susceptibility of the nervous and muscular organs presented particular phenomena, depending on the difference in the causes of asphyxia. [CAS 03, p. 34, author’s translation]

Can I name one more experiment where electricity brought a dead dog back to life? I say dead; for they have taken away part of his brain: & in this state, they put him on the cake, & they electrify him: he comes back to life, breathing, strong, gets up on his legs as if to run away. One stops electrifying it, it falls back into the inertia & the numbness of death; one starts electrifying again, & the movement starts again. [BIA 77, p. 36 quoted in ROZ 77, vol.9, p. 429, author’s translation]

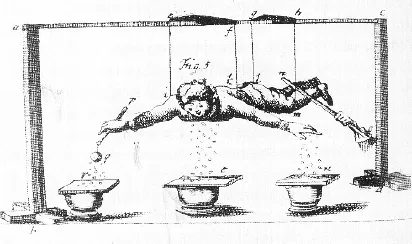

The epistemological status of animal electricity in the 19th Century was a symbol of life. It was made into a spectacle during the electrification of the bodies of those executed, who found themselves animated, without coming back to life, if we think of it in terms of consciousness. Like automatons, they were shaken by disordered movements that imitated those of the living. Medicine, marked by Cartesian dualism and 18th Century materialism, was able to experience the limits and properties of life on a Man who had become a machine. A symbol of atheism, revolution and reductionism, the experiments of the first third of the 19th Century contributed to the construction of a culture of physical, medical and sociological electricity. The bearer of hope, electricity was like the fire stolen by Prometheus to be given to humanity, and symbolized a materialistic progress where humans could gain access to knowledge and control over it. The notion of the electrical body, including its relationship with the soul, was constructed during the 19th Century through the study of the links between physics and the body. As a legacy of the 17th Century, the analogies of mechanics with human and animal physiology developed. Alongside the applications of electricity, the imagining of the mechanized body, obeying the laws of physics, was developing. While the way in which electricity connected the soul and the body remained a subject of speculation and questioning, the body became the site of investigations into the limits of life and the beginnings of death. How do gain control over these limits? Which organs help maintain life? How much room is there for the brain? The fact that the body could react to electrical simulations, that the heart starts beating again, was not enough to bring it back to life. The issues of the brain’s role in understanding human singularity were central to the applications of this exploratory electricity. In this way, organs acquired a very strong symbolic value that can still be found to this day. Aldini, Galvani’s nephew and colleague, spread galvanism beyond Italy’s borders, notably by electrifying the bodies of the tortured. The analogies between the galvanic cell and the organization of nerves and muscles, which seem to form organic circuits designed to conduct electricity, reinforced the idea that the body has a mechanics that can be known and mastered by the medical sciences. As early as 1791, electricity was considered the most important function of animal economics, especially for Joseph Priestley [PRI 67, 71] (1733–1804), for whom it revealed the nature of things. How can we understand the expression “culture of electricity”? If you look at it from a physical point of view, it’s hard to pinpoint. But if we consider from its very beginnings, the dimensions of spectacle and supernatural powers that surround its inscription in society, it becomes enlightening. Society was faced with a new technology, used as early as the first third of the 18th Century, as a trick and form of entertainment. Gray’s 1730 flying boy experiment is emblematic of these beginnings:

All metals, wood, reed or hemp, are conductors […] but also: soap bubbles, water, an umbrella, a slice of beef, or a young boy! [GRA 31–32, p. 35, author’s translation]

He did the first experiment on a child aged 8 to 10, suspended on two silk cords, in a horizontal position. Then putting the tube close to the child’s feet; his head, his hair, his face became electric; the same thing happened to his feet, when the tube was brought close to his head. [MAN 52, p. 10, author’s translation]

Electric shocks had become well known, so it was disguised in a thousand different forms. Everyone was eager, big & small, learned & ignorant, hastened to experience such a singular phenomenon on themselves. Thirty, forty, one hundred people at a time took pleasure in feeling the same blow & in shouting just one cry. [MAN 52, pp. 30–31, author’s translation]

On this principle, Mr. Franklin has imagined an electric wheel that turns with extraordinary force, & which, by means of a small wooden arrow raised perpendicularly, is able to roast a large bird in front of the fire, which is the...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 The Birth of an Electrical Culture: From Frankenstein to Hyde

- 2 From Physics to Electrifying Physicists

- 3 Controversial Electricity Applications

- 4 Animal Electricity: Between Medicine and Physiology

- 5 Between Electrotherapy Rooms and Laboratories: Specializing Electricity

- 6 Disorders and Resurgences of Electrical Neurostimulation Therapies: From Heath to Deep Brain Stimulation

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- References

- Index of Names

- Index of Terms

- End User License Agreement