1

Four snapshots of transgression

Snapshot 1: The dialectics of descent

No account of transgression in post-war art, however cursory, would be complete without a reference to the Viennese Actionists – a label first used by Peter Wiebel to describe the artwork of figures such as Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, Rudolf Schwarzkogler and Hermann Nitsch.1 Within its short lifespan of just six years (1962–8), the group performed acts that shocked the Austrian public and resulted in almost continuous criminal prosecution throughout the decade. Actions regularly incorporated animal carcasses, mock crucifixions, bodily fluids, and bloodletting, and together comprise a back catalogue whose justification frequently hinges on the dialectical play of opposites.

Dialectical oppositions can be found in the structure of individual works as well as in the relationship between the group and the socio-political context in which the works were made. The relevance of post-war Austria as a backdrop to the group’s actions has been well documented in art-historical writing, but this literature often narrowly focuses on the socio-political events that took place before and during the group’s short, intense lifespan.2 At the end of this chapter, some aspects of how this context has changed will be considered, making it possible to assess the lasting significance of their particular brand of transgression. As the only group member still working in Austria, largely in the same artistic idiom as he did in the 1960s, a more narrow focus on the work of Hermann Nitsch will provide a useful vehicle to look at this change.

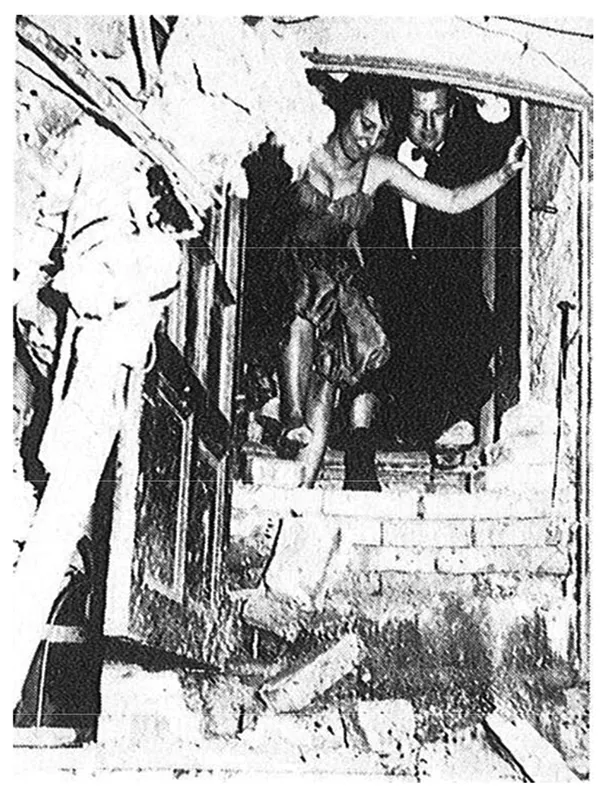

It is in anticipation of one of the group’s first collective actions that Nitsch, in a matter-of-fact tone, announces his plans for a piece that has since become a touchstone for transgressive art: ‘On the 4th June, 1962, I shall disembowel, tear and pull to pieces a dead lamb.’3 The action, collectively titled The Blood Organ, took place in the summer of 1962 in a cellar belonging to Otto Mühl in the Perinetgasse district of Vienna. Nitsch, Mühl and Frohner announced that they would be interning themselves in the cellar for three days and nights without food, with a newly constructed brick wall blocking the entrance and thereby preventing them from leaving (in fact the artists had made sure there was a back door allowing free access for the duration of the performance). Once inside the cellar, Nitsch alternated between working on the dead lamb, using his hands, teeth and tools to tear, chew and slice the animal, and creating a nine-metre long drip-and-pour painting. Mühl and Frohner created a number of sculptural assemblages individually that then merged into one another. At the end of this period, the public and members of the press were assembled to witness the literal and metaphorical ‘opening’ of the show. A woman wearing high heels and a ball gown was instructed to kick down the brick wall separating the performers from their audience (Figure 1.1), and the flashlights of the press photographers revealed the results of three days of activity. In a matter of hours the police had arrived, and the exhibition was promptly closed.4

The first, brutal performance by the group was followed by several more, culminating in Nitsch’s last public performance on 23 April 1967, when a particularly chaotic event in a Viennese restaurant entitled Zock-Fest ended in the arrival of two hundred riot police and their dogs. The following year, the remaining members of the group participated in a notorious event at the University of Vienna entitled Art and Revolution. At the invitation of the Austrian Association of Socialist Students, Brus, Mühl, Peter Weibel and Oswald Wiener staged a series of provocations in a lecture theatre that began with a speech insulting the recently murdered Robert Kennedy, as well as the Austrian minister of finance Stephen Koren (Mühl and Weibel), continued with Brus cutting his chest with razor blades, drinking his own urine, defecating on stage and smearing himself with his own faeces while singing the national anthem, and ended in Mühl whipping a masochist and drinking beer before organizing a pissing contest on stage. All the while Oswald Wiener attempted to deliver a lecture on consciousness and cybernetics, and Weibel set his arm on fire while giving a talk on the Leninist question ‘What is to be done?’5

Such riotous events constitute high water marks in the history of transgressive art. However, their reputation is not predicated solely upon the actions themselves. Extremity alone is no guarantee that an artwork will attain canonical status. Of more significance is the relationship between such extremity and the prevailing socio-political conditions. As Badura-Triska and Kandutsch note, the post-war climate of Austria exhibited many post-fascist traits.6 Public discussions addressing Austria’s role in the war had not yet begun, and after the war many influential positions in civic society were repopulated with former Nazis or Nazi sympathizers. Fascist ideology still saturated political institutions and influenced a cultural climate that Gerald Raunig describes as ‘rigidly conservative’.7 In this context the choice of the cellar as a site for their first action is significant. It both served as an approximation of the kinds of spaces in which the victims of Nazism met their death and represented the physical corollary of a psychological ‘depth’ to explore. When The Blood Organ came to an end, this private space was opened to the glare of the public spotlight, and the repressed libidinal energies were supposedly unleashed for the psychic good of Austrian society. Such therapeutic intentions were openly declared by Nitsch before the performance when he wrote that ‘Through my artistic production … I take upon myself the apparently negative, unsavoury, perverse, obscene, the passion and the hysteria of the act of sacrifice so that YOU are spared the sullying, shaming descent into the extreme.’8 Nitsch’s talk of a ‘descent’ highlights his fidelity to this depth model of the psyche, and his writings freely synthesize the work of Jung, Freud and Reich – the latter two being intellectuals the National Socialists had expelled from Austria.9 Above all else, however, it is a fairly narrow appropriation of the Freudian theory of abreaction that underpins the work, whereby pent-up instincts are released in a supposedly liberating discharge.10 In the now voluminous literature on the group, following up such stated psychoanalytical intentions has, perhaps unsurprisingly, become a dominant means of interpreting their output.11 Rather than follow these arguments here, it will be more instructive to look at the way in which they were mobilized at the time to justify the work’s transgressive content.

The need to justify their work was clearly felt by the Actionists, and the burgeoning discourse of psychoanalysis serves as a means to actively proclaim the social good of their actions, rather than resort to the kinds of formal defences that have been used to defend other transgressive art, from Manet to Mapplethorpe.12 To the rational, repressive law of the state the Actionists opposed a law of the psyche, which functioned as a repository of ‘instinctual’ energies and repressed traumas. The therapeutic benefit of working through traumas and channelling energies was upheld over and above the right of the state to maintain an order that was deemed repressive. Here it is not so much that psychoanalysis is inherently dialectical in itself; rather, it is the way in which it is mobilized that embodies a dialectical logic.

This relationship between two competing rights is mirrored by a second dialectical play that can be discerned in The Blood Organ itself. In this performance the wall separating the cellar from the street is not simply an analogue for the ego’s barricade against the chaotic libidinal energies of the Id – the surface against the depth – it is also a temporary barrier between a group of artists wishing to break with culturally sanctioned norms of behaviour and the state apparatus that wants to keep them in place. In short, it is the physical manifestation of the boundary separating the law from its inverse: transgression occurring when the two come into contact. By staging this moment of contact between two forces – one residing in the private sphere of the cellar, the other in the public sphere of the street – the Actionists sought to expose the strong arm of the state and jump-start the juridico-legal powers it wielded. Phillip Ursprung even argues that ‘the state was the main addressee of Austrian Actionist politics, [and] the police were the “ideal” audience’.13 In other words, there was a dynamic of engagement built into the very structure of the performances themselves. Duab furthers this point with a discussion of the photographs of the actions that were commissioned by the group and often later used as evidence in court. As he argues, these allowed relatively private performances to be ‘preserved by and integrated into the punitive and penal public discourses through which Austrian cultural politics has frequently and traditionally proceeded’.14 For Daub this argument extends to the group’s choice of titles such as Blood Orgy, which when performed in London supplied the press with a ready-made sensationalist headline – the front of the Evening Standard reading ‘Fleet Street “Blood Orgy” – 2 For Trial’.15

The group’s anticipation of scandal reveals a strategic understanding of the points of passage between public and private, repression and expression, and ultimately the law and transgression. But to what extent can we say that these oppositions are truly dialectical in their interrelation?

As Hegel claims in his analysis of tragic theatre, where he finds an exemplary set of dialectical movements, the central dynamic is one of collision between two competing rights, rather than a simplistic opposition between good and evil. There is some good to be found on both sides, and the resulting catastrophes that define the narratives of Aeschylus and Sophocles come about because the opposing sides adhere to one value system alone, blinding them to the other’s competing right. As Hegel writes of Antigone and Creon, each sees