![]()

1

How Counterculture Helped Put the “Vernacular” in Vernacular Webs

Robert Glenn Howard

IN 1964 STUDENTS CONVERGED ON THE UNIVERSITY OF California’s Sproul Hall. Protesting new policies that radically limited political speech on campus, some of these students wore punch cards, used to input data into the era’s computers, around their necks. One protestor had a sign suggesting computers were a mechanism of oppressive institutional power: “I am a UC Berkeley student. Please do not fold, bend, spindle, or mutilate me” (Turner 2006, 2). In 1964 the computer could be invoked as a symbol of oppression. Some twenty years later, however, it had been transformed into a symbol of freedom. In January of 1984, Apple Computer announced its new Macintosh computer system. In a now iconic commercial, the Macintosh was presented as the liberating force that would keep George Orwell’s dystopian vision of an autocratic future in his book 1984 from becoming a reality.

The commercial depicts what seem to be automatons watching a huge projection of a man orating, “We have created, for the first time in all history, a garden of pure ideology—where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests purveying contradictory truths … Our enemies shall talk themselves to death, and we will bury them with their own confusion!” As the man speaks, a woman with short, blond hair bursts into the auditorium, with helmeted guards in close pursuit. She wears bright red running shorts and a tank top bearing the new Macintosh logo. With a powerful swing, she hurls a sledgehammer through the screen and shatters it. A blinding flash of white light washes over the startled automatons. The commercial concludes, “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you will see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984’” (“Apple’s 1984 Commercial” 2011).

What happened? How had computer technologies been transformed from the oppressive mechanism of institutional control to a liberating force of empowered individualism? The simple answer to that question has far-reaching implications.

Only institutions with significant financial resources (like governments, large corporations, and major research universities and institutes) could afford to operate the expensive, large, and operationally complex computers of the 1960s. A decade later, individuals influenced by the counterculture movement of the 1960s developed personal computer (PC) and Internet technologies, infusing them with a sense of anti-institutionalism. Because the development of these two key technologies shifted the computer industry’s focus away from institutions toward everyday people, the forms of online communication we see today bear traces of an ideology that values the “folk,” or vernacular, over the institutional. The iconic Apple Computer commercial explicitly conveyed this ethos some ten years after the creation of the first personal computers. Today’s computer users have been empowered by this ethos to create and consume their own complex media content alongside, but apart from, the content created by powerful institutions. The dynamic and interlocking networks of everyday personal connection that we create online now constitute powerful new webs of vernacular communication.

This chapter traces how a valuation of the vernacular came to be embedded in network communication. I first locate a rhetoric of vernacular authority that emerges in an amateur publication highly influential among hobbyist computer users of the 1970s: the underground introduction to computer programming and manifesto Computer Lib (Nelson 1974). This publication first popularized the idea of hypertext as a technology that could wrest the power of computers from institutions and bring it to the people. Ultimately, hypertext would become the basic technology that made vernacular webs possible. I next examine the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter. Here, another group of computer enthusiasts expressed the same valuation of the vernacular as they sought to create a personal computer that anyone could own and use. Prominent newsletter readers included Microsoft founder Bill Gates as well as the founders of Apple, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. From the Homebrew newsletter, the second key technology of vernacular webs took shape: the personal computer itself.

Next, I describe how these communities’ vernacular ethos emerged in the institutionally funded development of the basic computer code behind all Internet communication. But it was not until institutionally funded websites emerged that vernacular webs became observable online. Only afterward did it become possible to see the difference between everyday Internet use and more formal institutional Internet use. Finally, I demonstrate how the hybridization between institutional and vernacular influence is now inextricably woven into the vernacular webs of today. Although commercialism and institutional authorities certainly have a role in shaping the expressive behaviors that comprise vernacular webs, that fact should not keep researchers of everyday expressive behavior from looking online. The very technologies that make online vernacular communication possible also render that communication hybrid, and folklore scholars’ expertise with everyday expression places them in a unique position to document and analyze the complexity arising in network environments.

Vernacular webs are, in many ways, nothing new. We humans have always devised clever ways to express ourselves to each other, and we have always done so by drawing from both institutional and vernacular sources of influence. However, as these new technologies press older analog media into the background, vernacular webs are creating a renaissance of everyday expressive communication rife with dynamic new forms of digital folk culture; this vibrant new arena presents powerful new research opportunities for scholars of everyday expression.

COMPUTER LIB

Theodor “Ted” Nelson self-published Computer Lib: You Can and Must Understand Computers Now/Dream Machines: New Freedoms Through Computer Screens—A Minority Report (or Computer Lib for short) in 1974. Half computer textbook and half fanzine, it was widely read by the small community of computer hobbyists of the mid-1970s (Abbate 1999, 214). Nelson’s book gave voice to anti-establishment hippie-hackers who saw themselves standing in opposition to the powerful institutions of corporations and governments. Nelson argued that everyday individuals must learn to use computers because only computers could liberate them from institutional oppression.

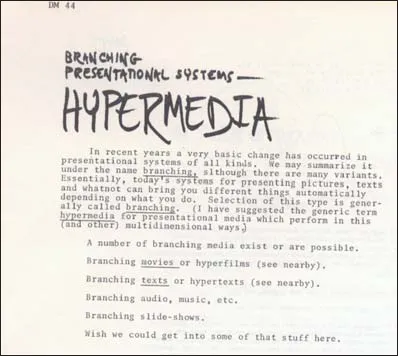

In trying to make computers easier to use, Nelson imagined new kinds of computer interfaces he called “presentational systems” based on “branching” instead of hierarchical organization. In such systems, individuals could more easily access the information collected onto institutional computers. A branching system would shift the authority for the organization (the order and number of ideas accessed) to each individual user, privileging vernacular authority over institutional authority in the accessing of information. If authority is the power to determine what content is consumed and in what order, Nelson’s systems would seek to frustrate the author-function of a traditional book or other media object where the order and parts of the content consumed are more subject to determination by the author or other content producers. The author of a book, after all, usually indicates which page is the first page a reader should read by numbering that page “1.”

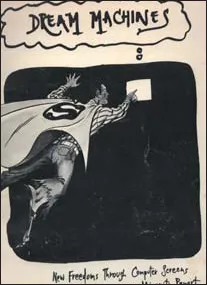

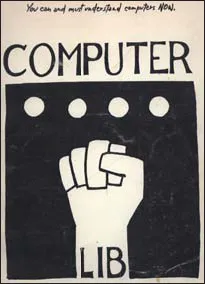

Exemplifying how such systems could work, Nelson’s book, in contrast, seeks to frustrate this convention by having two first pages. Combined with other presentational system qualities, the book is an exercise in patience to read. After spending many hours with it, the reader is still not sure if she or he has read the entire thing because its structure has quite effectively made it impossible to read in any linear sequence. Figures 1 and 2 show the most obvious way Nelson tried to create a branching informational system: he gave it two front covers. From one side, Dream Machines: New Freedoms through Computer Screens—A Minority Report is, literally, a computer programming tutorial containing introductions to APL, BASIC, and other computer languages of the day.

Read from this cover, the book begins by offering Nelson’s “credentials”: a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and a master’s in sociology from Harvard University. If read from the other side (the Computer Lib side), Nelson’s “counterculture credentials” include “a year at Dr. Lilly’s dolphin lab” and “attendee of the great Woodstock Festival”(CL 127 [DM 1]).1

Throughout, the book offers manifestos, cartoons, mathematical equations, programming diagrams, quotes from computer textbooks, and descriptions of new technologies, both real and imagined. Nelson presents all this in a mix of often tiny typewritten and handwritten text blocks, graphics, and cartoons that seem to compete with each other for space on the pages as well as the reader’s attention.

On one page, Nelson overtly references his choice of this confusing layout as an attempt to encourage readers to “jump around” and “try different pathways.” He describes his choice in layout writing this way: “The astute reader, and anybody who’s [sic] gotten to this point must be, will have noticed that this book is in ‘magazine’ layout, organized visually by ideas and meanings … I will be interested to hear whether that has worked” (CL 85 [DM 44]).

Figure 1.1. Dream Machines front cover, 1974.

Figure 1.2. Computer Lib’s other front cover, 1974.

For many readers, this format is more a challenge to overcome than an effective informational system. However, for the computer hobbyists of the mid-to late 1970s, the book was a printed representation of what they imagined a future medium would be able to do: overcome the limitations of print. For them, this vision of a branching presentational system could empower individuals to “build-from-the-bottom” by giving them more control over their access to information. By forcing the reader to choose from which cover to start reading, the two front covers at least symbolically shift some of the authority from the author to each individual reader. In this sense, reading the book forces the reader to enact her or his own vernacular authority to determine the specific ideas and order of the information one accesses from the book. In 1974, however, the actual technologies of the Internet would not make these kinds of systems more practical for a long time:

Deep and widespread computer systems would be tempting to two dangerous parties, “organized crime” and the Executive Branch of the Federal Government (assuming there is still a difference between the two). If we are to have the freedoms of information we deserve as a free people, the safeguards have to be built at the bottom, now. (Nelson 1974, CL 70 [DM 59]; his underlining)

In the early 1970s, before the wide availability of personal computers like the Apple II, computers were so large and expensive, they were almost exclusively owned by large institutions (Ceruzzi 2003, 109–141; Freiberger and Swaine, 1984, 204–205). As a result, people generally seem to have imagined them as distant institutional mechanisms. On the rare occasions when the general public could access computer terminals, most people found them too difficult to use. Before the graphical user interfaces, or “GUIs,” and the emphasis on ease-of-use common today, individuals were required to have significant technical skills to actually use computers of any kind. At the time of Computer Lib, the technical challenges presented to users compelled Nelson to argue that everyone should have some knowledge of computer languages. This was the motive behind his book’s instructional component.

For Nelson, computer skills needed to be more widely distributed so that vernacular voices could be better heard. He described a “computer priesthood” that withheld knowledge by refusing to construct computer systems in the vernacular of everyday people. He asserted, “Knowledge is power and so it tends to be hoarded.” For everyday individuals to stand a chance against technologically empowered institutional forces, he argued, “It is imperative … that the appalling gap between public and computer insider be closed … Guardianship of the computer can no longer be left to the priesthood” (CL 52 [DM 76]). Nelson figured himself as a computer nerd Robin Hood. A noninstitutional agent, he and his computer-hobbyist colleagues hoped to bring computers from the mountaintop to the masses by distributing computer skills more widely among the population. At the same time, they imagined developing branching informational systems that would be much easier for these newly computer-empowered folk to use. The difficult layout of Computer Lib invoked the folk-friendly systems he and his colleagues imagined for the future.

While the difficulty of Computer Lib seems to have kept it from directly reaching a popular audience, the central idea it attempted to exemplify would eventually come to affect us all. While advocating ways to build at the bottom with branching informational systems, Nelson described and advocated for what he termed “hypermedia.”

Figure 1.3. “Hypermedia” in Computer Lib, 1974.

For Nelson, using hypermedia instead of hierarchical organization would link information in more intuitive ways and thus encourage egalitarian access that gives the power of what and how knowledge is constructed to everyday people instead of institutions. Making this argument, Nelson became a countercultural hero championing the folk through his advocacy of hypertext as a form of branching or nonsequential writing. These technologies would counteract the power of institutions as held by the computer priesthood (CL 85 [DM 44]). Of course, the desire for a real-world application of Nelson’s hypertext idea would later drive another hippie-hacker to develop the basic technology of the early World Wide Web in the form of the HTML computer language.

But even before individuals could use any sort of hypermedia, they needed a networked computer that could link the branching media. At the time, everyday people didn’t have access to so-called minicomputers that were large and expensive and available only to institutions. The public needed something smaller and cheaper to plug into these imagined networks of branching media. In the next section, I look at the newsletter produced by the Homebrew Computer Club. Founded only months after Nelson released Computer Lib, active members of this club included some of the most important figures in the development of personal computer technologies. Much like Nelson had imagined vernacular empowerment through computer programming, many Homebrew club members were imagining new avenues for empowerment made possible by the creation of small, cheap, and widely available personal computers.

THE HOMEBREW COMPUTER CLUB NEWSLETTER

By 1974, a number of San Francisco Bay Area individuals had formed informal mechanisms for exchanging information about computers, computer programming, and electronics. At the time, a local activist named Fred Moore had started something he called the Whole Earth Truck Store in Menlo Park, California, as a way to create connections between people who wanted to share information outside of what he felt were oppressive institutions. Thinking that maybe a computer could help him, but not knowing much about them, Moore contacted a computer club called the People’s Computer Company. Soon he was learning about, and loudly advocating for, computers as a source of noninstitutional empowerment (Freiberger and Swaine 1984, 104).

Meanwhile, the January 1975 cover of the hobbyist magazine Popular Mechanics featured the Altair 8800 Computer. An Arizona company sold the Altair as a minicomputer by mail order for only $400. The computer itself was little more than a metal box with LED lights on the front. However, the chip inside the box was an Intel 8080 (Ceruzzi 2003, 228). Intel had designed this chip at a time when that level of computing power was only available in the far more expensive and larger computers purchased by businesses, government agencies, and universities. As a result of new production technologies that dramatically reduced costs, however, the $400 Altair could house a chip with similar processing power to that of the 1974 IBM System/370 Model 115, which had a base price of $265,165. The LED-equipped Altair, however, did not come with screens, keyboards, or even software (IBM 1974).

Learning of the availability of the bare chip, H. Edward Roberts, of a small company called MITS, cut a deal to buy them in quantity from Intel for only $75 apiece. This was made possible because the cost of producing a chip was in the design and setup of its manufacturing. Once a single chip was built, it was very cheap to make many more chips. Because the Altair was not competing for the IBM System/370 Model 115 market (having no out-of-the-box functionality other than blinking lights), Intel could sell bare chips very cheaply (Ceruzzi 2003, 395n). But who would want a computer chip in a box? It had no keyboard, monitor, disk drive, or game controller. Roberts’s genius was to realize that he could sell basically just the chip to computer hobbyists as a “kit” for $400 and turn a decent profit. Hobbyists wanted the chip because it was a “computer”—something usually only institutions could afford. While most people would find the Altair useless, hobbyists immediately recognized that they could build components to add whatever functionality they could imagine to the computer.

When Fred Moore heard of the Altair, he contacted everybody he knew who was associated with the People’s Computer Company and interested in “building their own computer” to join him in a friend’s garage on March 5, 1975. This informal gathering constituted the inaugural meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club. Thirty-two computer-hobbyist hippies came from all over the Bay Area (Freiberger and Swaine 1984, 104). While several of the new club’s members began producing the now-famous newsletter, other members went right to building basic components to expand the Altair’s functions. Not long after, Bill Gates famously rewrote the BASIC computer language so that it could be saved on a cassette tape and loaded into the expanded memory banks that users added to their Altairs. Later, Gates would print his “Open Letter to Hobbyists” in the Homebrew news-letter—a document often thought to mark the emergence of the software industry itself because it was the first in a popular publi...