eBook - ePub

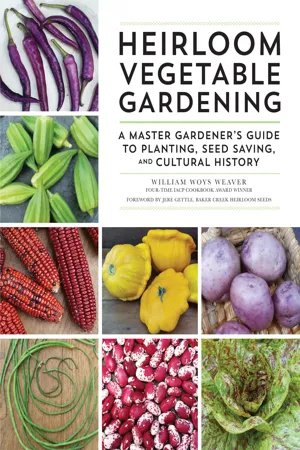

Heirloom Vegetable Gardening

A Master Gardener's Guide to Planting, Seed Saving, and Cultural History

William Woys Weaver

This is a test

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Heirloom Vegetable Gardening

A Master Gardener's Guide to Planting, Seed Saving, and Cultural History

William Woys Weaver

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

"This book is sure to be a modern classic and is one of the most important books on gardening in the current century."

—Jere Gettle, founder, Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds Heirloom Vegetable Gardening has always been a book for gardeners and cooks interested in unique flavors, colors, and history in their produce. This updated edition has been improved throughout with growing zones, advice, and new plant entries. Line art has been replaced with lush, full-color photography. Yet at the core, this book delivers on the same promise it made two decades ago: It's a comprehensive guide based on meticulous first-person research to these 300+ plants, making it a book to come back to season after season.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Heirloom Vegetable Gardening est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Heirloom Vegetable Gardening par William Woys Weaver en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Sciences biologiques et Horticulture. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Sciences biologiquesSous-sujet

HorticultureCHAPTER 1

THE KITCHEN GARDEN IN AMERICA

In the Greek of Homer, the word for leek, práson, was also the root word for a garden bed: prasia. Such a linguistic connectedness between the kitchen vegetable and its place of cultivation does not exist in English. When the Anglo-Saxons invaded Britain, they found an indigenous Celtic culture focused on cattle breeding and husbandry, which they too adopted. Thus, we have inherited a linguistic and cultural perspective of the garden much different from that of the Mediterranean peoples.

This is not to say that we were never a nation of gardeners; but as a country that became heavily industrialized in the nineteenth century, much of America lost its daily contact with the land. Today we must consider the old metaphor of the leek against the international symbols of American cookery: the hamburger and French fries.

Since the coming of industrialization, we have gazed nostalgically toward the Mediterranean for guidance, for a return to the birthplace of “real food,” for a recovery of color, taste, and aroma. This mythology was created more than a hundred years ago by writers like Janet Ross, whose Leaves from Our Tuscan Kitchen; or, How to Cook Vegetables (1899) offered consolation through escape. It is a genre of writing that has sold steadily ever since; the world of the émigré epicure is a world exactly as he wants it. The Mediterranean happens to be one of the last agricultural fringes of Europe. It is false history to imagine that other parts of the Continent in preindustrial times did not also enjoy similar pleasures of peasant simplicity or directness of connection between garden and hearth. Yet the Mediterranean has the advantage, at least in European terms, of preempting the rest by virtue of the civilizations it produced in the past. This obvious historical fact must serve as a constant reminder to the American horticulturist that we did not start at ground zero in the recent past, whether we define that as 1492, 1776, or the date on great-grandfather’s immigration papers. Our gardening and culinary histories began elsewhere and are a continuation of something basic and human with deep roots in classical antiquity. This is the long view of history that characterizes my work as a writer, food historian, and gardener.

Finger Squash, shown here with other heirloom squash and Roughwood Fiesta sweet corn, is a Native American variety documented as early as the 1770s.

I have always held the belief that American cookery will not evolve its underlying character beneath the artificial lights of a professional kitchen. It is a more holistic process that involves sunshine as a major ingredient. It begins in the kitchen garden, where the cook moves among ingredients still attached to the soil. It was like that one time in America, even if only an idea acted out in its most elaborate forms by the well-to-do like Thomas Jefferson or William Hamilton of Philadelphia.

Let us not forget that Amelia Simmons, author of the first American cookbook in 1796, also wrote about the vegetables in her kitchen garden and remains even today highly quotable on this subject. Henrietta Davidis, the most popular German cookbook writer in the nineteenth century and a proponent of middle-class fare, also wrote books about kitchen gardens and vegetables. Her most famous cookbook was published in German at Milwaukee in 1879 and served as a household bible for a large segment of the Midwest in the late nineteenth century.

It is not necessary to smell the sea from beneath the bending limbs of an olive tree to experience the rejuvenating sensuality of a landscape dotted with garden plots and flowers. We have our own Peaceable Kingdoms in America, if only we would go outside to behold them and learn their simple pleasures. Our gardens are full of plants with stories, many of which I will relate in the following pages. They bring into the kitchen pedigrees as perennially fresh as the plants themselves, and knowing them, understanding their past, is not just part of savoring the added dimension these heirlooms lend to our daily experience; it is also a means of acquiring a certain kind of knowledge that made the “particular customer” of yesteryear. The market gardeners at the turn of the last century lamented the decline of this selective and well-informed consumer because with this decline in care for ingredients came a decline in cookery. The rest is history.

THE CLASSICAL ROOTS

We know from botanical treatises and archaeological evidence surviving from the Roman world that there were recognized varieties of many common garden vegetables: carrots, turnips, leeks, cabbages, and cucumbers, to name a few. We also know that gardening techniques were highly developed, certainly in the gardens of the wealthy. Onions, for example, were cultivated in special beds called cepinae, and the gardeners who maintained them were known as ceparii. This type of specialization provides clues about the refinement of cookery and philosophical connectedness between the ancient Roman kitchen garden and hearth, but it tells us little about the vegetables themselves, what they looked like or how they tasted.

American archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski has tried to address some of these issues by actually digging into ancient garden soil. Her Gardens of Pompeii (1979) is widely cited for its treatment of Roman ornamental gardens, landscaping, and even vineyard layouts. In many cases, she was able to connect botanical subjects in fresco paintings with actual plant remains preserved in the ground, or with similar plants extant today. I was delighted to discover that my pale pink oleander matches one in a fresco at the House of the Fruit Orchard in Pompeii. So I will always imagine that it was the goddess Flora who scattered my oleander petals across the lawn, and that lurking behind my lemons is a turtledove cooing softly to Pan. But search as we will for clues in ancient frescos, there is next to nothing about Roman vegetables or the Roman version of the jardin potager, the place where the modern French grow their culinary ingredients. I suppose, to the Roman mind, such subject matter would have been equated with painting views of a kitchen sink.

Yet there are ways to discover ancient vegetables from other perspectives. For example, we can create inventories of the plants that we know were cultivated in classical antiquity and ascertain whether there are surviving examples today—there is even a small circle of heirloom gardeners who specialize in such ancient foodstuffs. Those garden vegetables, with their richly documented histories, are the true undisputed heirlooms of antiquity. Most of the world’s cultures can claim such heirloom plants, whether from the New World or the Old.

From the Roman world we know that the leaves of horsetooth amaranth (shown here), the bliton of the ancient Greeks, were cooked like spinach and used as stuffings or in pesto. The ancient Gauls used the arrow-shaped leaves of Good King Henry (shown here) to fatten chickens for special feasts, as well as rabbits and young geese. A perennial herb related to lambs-quarters and quinoa, it was incorporated into the green sauces served with these meats. Marshmallow was considered a delicacy, its young flower buds cooked as a potherb (very similar in texture to okra) and its boiled roots stir-fried with onions and drawn butter. I grow these ancient vegetables, and I have prepared them according to antique recipes. But the results were never completely satisfactory, because I have no way of knowing what cultural tricks Roman gardeners employed to make the vegetables more palatable. All we have to work with are plant survivors that have reverted more or less to a wild condition.

When plants are preserved by man, generation to generation, seed to seed, the gardener intervenes in nature, for we are maintaining them in an artificial state desirable only to us, as in the huge variety of tomatoes and the many forms of beets. This is not a natural condition; it is natural for plants to undergo constant adaptation and genetic change. That is how they ensure their own survival. Therefore, even as I may admire a Pompeian fresco with a pink oleander like one in my garden, I must hasten to remind myself that the two are similar but not the same. This is a basic rule in understanding the nature of all heirloom vegetables. Genetic change is inevitable.

Shetland Kale is one of the oldest surviving varieties of hardy kale tracing to Celtic Britain.

We know that many common vegetables have undergone gradual genetic alteration, because there is pictorial evidence to prove it. It is evidenced not in stylized fresco paintings but rather in a manuscript medical book surviving from the Roman era. The Codex Vindobonensis Medicus Graecus of Dioskorides, written in A.D. 60, was copied at Constantinople between A.D. 500 and 511 and illustrated with hand-colored pictures. The original manuscript survives in the Austrian National Library at Vienna, and many of the plants depicted in it include such familiar vegetables as radishes, cowpeas, and fava beans. In several cases, these are the oldest known “scientific” pictures of certain vegetables, and for this reason I will refer to the codex of Dioskorides from time to time in the course of this book.

The German botanist Udelgard Körber-Grohne has analyzed the vegetable illustrations in the codex of Dioskorides in her Nutzpflanzen in Deutscbland (1988) and set this material in the context of plant archaeology. Because she also raises heirloom vegetables from the ancient world in her garden at Stuttgart, her firsthand knowledge of plant behavior sets her work apart from others in the field. Körber-Grohne’s research is useful because it creates a continental European framework for the origins of the American kitchen garden and many of the Old World vegetables associated with it.

The fava bean illustrated in the codex of Dioskorides presents an intriguing case study, because it is the fava bean of Roman cookery, not the fava we eat today. The two are distinctly different varieties. The plant shown in the codex has a stout, stumpy stem, unlike modern favas. Archaeology has confirmed that this was a characteristic of the plant in ancient times. Because the plants were gathered after harvesting the beans and used as straw in barns, quite a few archaeological sites have produced intact carbonized specimens. Even more interesting, from the standpoint of cookery, the pods depicted in the codex are not like the pods of the modern broad bean.

The pod of the Roman fava (Vicia faba var. minor) was diminutive, resembling the common horse bean (Vicia faba var. equina) of today, or the medieval fava bean called Martoc (shown here), which has been preserved by seed savers in England. Carbonized favas from Roman sites prove that the seeds were small, like peas; some were even the size of lentils. This may be one reason why Roman cooks chose to puree the beans in many of their recipes, for the large broad beans that were once popular in colonial America did not appear until ...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword By Jere Gettle

- Introduction to This Edition

- Introduction to the First Edition

- Chapter 1 The Kitchen Garden In America

- Chapter 2 The Heirloom Vegetable Today

- Chapter 3 A Grower’s Guide to Selected Heirloom Vegetables

- Acknowledgments

- Commercial Seed and Plant Stock Sources

- Works Cited

- Index

- About The Author

- Dedication

- Copyright

Normes de citation pour Heirloom Vegetable Gardening

APA 6 Citation

Weaver, W. W. (2018). Heirloom Vegetable Gardening ([edition unavailable]). Voyageur Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2064616/heirloom-vegetable-gardening-a-master-gardeners-guide-to-planting-seed-saving-and-cultural-history-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Weaver, William Woys. (2018) 2018. Heirloom Vegetable Gardening. [Edition unavailable]. Voyageur Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/2064616/heirloom-vegetable-gardening-a-master-gardeners-guide-to-planting-seed-saving-and-cultural-history-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Weaver, W. W. (2018) Heirloom Vegetable Gardening. [edition unavailable]. Voyageur Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2064616/heirloom-vegetable-gardening-a-master-gardeners-guide-to-planting-seed-saving-and-cultural-history-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Weaver, William Woys. Heirloom Vegetable Gardening. [edition unavailable]. Voyageur Press, 2018. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.