Suppose you view a ripe tomato on a table. Your experience has a distinctive phenomenological character. An experience of a lemon on the table would have a very different character. The central question in the philosophy of perception is the character question. What is it to have an experience with a certain character? What do differences in the character of experience consist in?

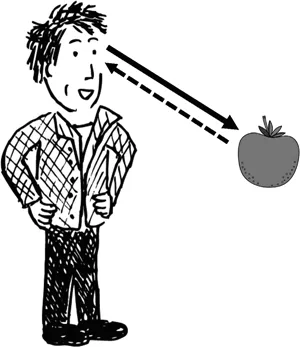

Naïve realists answer that for you to have the tomato-experience on this occasion is simply for you to experience the objective color and shape of the physical tomato itself. Experience involves a special mental relationship that “leaps the spatial gap” between you and the tomato. The character of your experience is simply constituted by your experiencing the bright redness of the tomato, its bulgy shape, and so on (see Figure 1.1).

Naïve realism. At least in normal cases, differences in the character of your experiences are constituted by your experiencing different states (colors, shapes, spatial layouts, sounds, smells, etc.) of mind-independent objects.

Here I am using “objects” very broadly to include ordinary things like tomatoes, pure visibilia like the sky and rainbows, events like the movement of a bird in your peripheral vision, and whatever else you might experience.

Naïve realism is in the first instance an account of the character experience. But it also makes a big assumption about the character of the world. In particular, it presupposes realism about sensible properties, such as colors, audible properties, taste qualities, and smell qualities. It requires that, even before we evolved, the physical world was replete with all these sensible properties. Tomatoes were red, the sky was blue, the whistling wind made a high-pitched sound, sulfur had a bad smell, and so on. The so-called “qualia” were already in the world. In some versions, these sensible properties just are objective physical properties, even if they seem very different from physical properties: redness-as-we-see-it just is a way reflecting light, smells are just chemical properties, audible qualities are complex physical properties involving frequency and intensity, and so on.

You might wonder how naïve realism coheres with scientific thinking about experience. Many ancient thinkers, including Plato, Euclid, and Ptolemy, accepted the extromission theory of the physical process underlying seeing. They speculated that we experience the world by way of rays emanating from the eye (perhaps with infinite velocity). As Euclid said, “Rays [proceed] from the eye [and] those things are seen upon which the visual rays fall and those things are not seen upon which the visual rays do not fall” (Gross 1999). If the character of experience is constituted by what objects and states of affairs we see, via the rays emanating from the eye, then this is a form of naïve realism.

In the early part of the 17th-century scientific revolution, the work of Da Vinci and Kepler established the opposing “intromission model” that we now all accept. In fact, well before them, Alhazen (c. 965–c. 1040) had already mounted an empirical case for the intromission theory. It is now part of educated commonsense that objects reflect light into the eyes. (However, it is interesting to note in passing that, according to a recent study (Winer et al. 2002), 60% of college students still accept the extromission theory!)

Now you might think that the intromission model of the causal process underlying experience immediately refutes the naïve realists' account of the character of experience. As Bertrand Russell said, “The observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if science is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself [and so] naïve realism is false” (1940: 15).

But naïve realists can resist this argument by accepting the window shade model of the role of the brain. For instance, go back to the example of viewing a tomato. Naïve realists can say that the long causal process from the object to the brain (the “inward-pointing arrow” in Figure 1.1) is what “opens the window shade” and enables you to experience the character of the object (the “outward-pointing arrow”). On this view, you do not experience the end result of the causal process that starts when light is reflected from the tomato and stimulates the receptors in your eyes, as Russell assumed. Rather, it is just a fact about the way perception works that you only experience the tomato that starts off the causal process. The brain processes play an enabling role: they enable you to experience the pre-existing color and shape of the tomato. They select what elements of the mind-independent world you get to experience.

You might wonder what naïve realists say about illusions and hallucinations. We will discuss that later. First we must understand the sense datum view.