eBook - ePub

The Sumerians

Lost Civilizations

Paul Collins

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Sumerians

Lost Civilizations

Paul Collins

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The Sumerians are widely believed to have created the world's earliest civilization on the fertile floodplains of southern Iraq from about 3500 to 2000 BCE. They have been credited with the invention of nothing less than cities, writing, and the wheel, and therefore hold an ancient mirror to our own urban, literate world. But is this picture correct? Paul Collins reveals how the idea of a Sumerian people was assembled from the archaeological and textual evidence uncovered in Iraq and Syria over the last one hundred fifty years. Reconstructed through the biases of those who unearthed them, the Sumerians were never simply lost and found, but reinvented a number of times, both in antiquity and in the more recent past.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Sumerians est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Sumerians par Paul Collins en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans History et World History. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

HistorySous-sujet

World History | ONEORIGINS |

After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu. In Eridu, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28,800 years.1

So read the first lines of the Sumerian King List. Although several versions of the List have survived, the most extensive, as well as the most complete, now resides in the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, many thousands of miles from the place where it was composed. It takes the form of a small block of clay, about the size of a modern house brick, known to specialists as a ‘prism’. Perforated through its length, perhaps so that it could be rotated on a vertical spindle for reading, the prism is inscribed on each of the four sides with two columns of wedge-shaped (cuneiform) script, used here to write the Sumerian language. Based on information in the text, this particular version of the King List can be dated to about 1800 BC. We are less clear, however, about precisely where it was written, since the prism had been sold in Iraq to the English collector Herbert Weld-Blundell shortly before 1923, the year he gave it to the Ashmolean along with many other cuneiform tablets (a story to which we will return later). It may have been plundered from the site of Tell as-Senkereh (ancient Larsa), one of the thousands of abandoned settlement mounds – often described by the Arabic word tell – that lie scattered across the flat plains of southern Iraq.

The document lists a succession of cities, their rulers and the length of their reigns. It is not history as we would understand it, but a combination of myth, legend and historical information.2 This is a work of scholarship, carefully crafted by learned scribes to connect the politics of their own time with the mythological origins of kingship in a deep past. It seems to have been composed to imply that the dominion of Mesopotamia (the region comprising approximately present-day Iraq and eastern Syria) could only be exercised by one city at a given time and for a limited period as determined by the gods – and for these particular intellectuals it all began at Eridu.

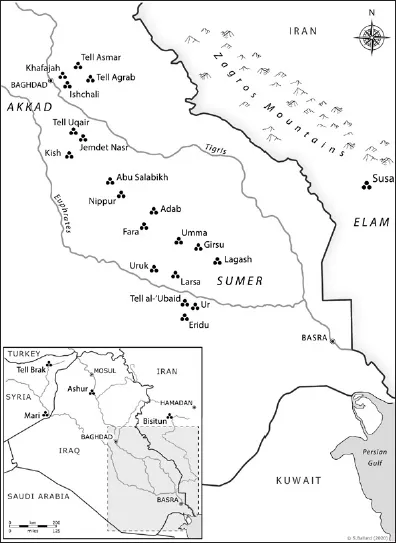

What remains of Eridu lies today in a dusty, featureless desert, some 35 km (22 mi.) west of the River Euphrates in southern Iraq. Six thousand years ago, however, the headwaters of the Persian Gulf lay much further north than they do today, and the small town was surrounded by freshwater reed marshes, fertile alluvial soil and waterways giving access to the open sea. Life was based on fishing and the herding of cattle, sheep and goats, together with the cultivation of wheat, barley, apples, figs and groves of date palms. Eridu was one town in a network of settlements that had developed on the riverbanks across a landscape of flood plains formed by branches of the Tigris and Euphrates in the southern half of Mesopotamia.

As early as 2500 BC, Mesopotamian texts link Eridu with the god Enki, whose temple was located there. He was the god of sweet, fresh water and therefore closely associated with its life-giving properties. Over time, however, Enki also came to be identified as the source of divine knowledge that had, at the very beginning of time, established civilization, which was understood as the rule of kings. To the scholars of Mesopotamia, looking back in time for the start of something significant had become important for understanding their present.

The search for such beginnings is a familiar concept to us. Magazine articles, books, television series and museum exhibitions all recognize people’s fascination with the origins of things, whether that be the first humans, the earliest farmers, the world’s oldest cities, the start of writing, the birth of art and so on. These moments act as markers in time that can in some sense be grasped in the longer history of humanity and also offer ways of explaining familiar features of our own world. Such an approach comes, however, with challenges. When we ask a seemingly straightforward question about the beginning of something, it can very quickly devolve into debates over semantics – what do we mean exactly by terms such as ‘city’, ‘writing’ or ‘art’, or indeed when exactly can anything be said to truly start? For most modern historians, the past is less a series of firsts or even specific events and more a complex process of change over time. Nonetheless, a general fascination with origins persists, and this is often linked to questions about the rise of ‘civilization’. This is another term that is difficult to define very clearly. It is often represented by a list of specific (depending who is selecting them) technical or aesthetic achievements, or understood as representing a particular stage of cultural development. Civilization has been – and very often still is – viewed as a process by which a society or place reaches an ‘advanced’ stage of social and cultural development and organization, often by comparison with Western societies, which are viewed as the most complex (and therefore superior) way of living. The current difficulties in defining these terms were not always so apparent, and, as we will discover, certainties about their meanings have been fundamental in shaping how the Sumerians have been understood and imagined.

Map of southern Mesopotamia showing sites mentioned in the text.

As was the case in Mesopotamia, looking back in time always serves some purpose in the present. We in the West (problematic as this simplified term is) have incorporated a number of past cultures and peoples into our own history and identity, often in relation to their role in shaping our ‘civilization’. Some play large roles, such as ancient Greece and Rome; ‘rediscovered’ by the West, starting with a fourteenth-century Renaissance, they have come to embody notions of perfection and order, especially in politics and aesthetics. Other ‘lost’ civilizations that were ‘discovered’ by Western adventurers and archaeologists include ancient Egypt, which today occupies a seemingly very familiar place in our lives; through the ‘mysteries’ of hieroglyphs, pyramids and mummies, it presents a heady mix of orientalized otherness but with imagined accessibility.3 The societies of Mesopotamia, albeit less overtly, have also played their own distinct role in shaping mainstream Western culture. Like the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians, some of the region’s peoples, such as the Assyrians and Babylonians, were never entirely ‘lost’, since echoes of them persisted in biblical and classical accounts, which were widely read and quoted in the West, as well as in Arabic and Persian texts, which had a much narrower circulation outside the regions where those languages were spoken. In European imagination, the Assyrians of northern Mesopotamia were associated with biblical oppression, but with the uncovering of their royal palaces at Nimrud and Nineveh in the mid-nineteenth century they could be linked with Victorian enterprise and science (so, for example, King Sennacherib, who established Nineveh as the Assyrian capital around 700 BC, is depicted on the Albert Memorial in London’s Hyde Park as the embodiment of engineering). At the same time southern Mesopotamia was understood as the home of the Jewish Patriarch Abraham and the site of the Tower of Babel.4

The Sumerians, however, were completely unknown – and not just in the West – until some 150 years ago, when they began to be untangled and constructed from the archaeological and textual evidence uncovered in Iraq and Syria. The mysteries of who they were, where they came from and what they looked like were so difficult to define, at least initially, that they were never imagined or claimed to the same extent as were places such as Egypt, which had a much longer relationship with Western thought. They had no iconic monuments, such as the Egyptian pyramids, for example, that had withstood the ravages of time and through which a connection might be established.

The Sumerians were first ‘discovered’ in the second half of the nineteenth century, by which time European states, supported by military power, had established conditions in which explorers, diplomats, merchants and scholars could travel to Mesopotamia, record their impressions and bring home objects as souvenirs for their own enjoyment or for display in museums. To European eyes, the modern ‘Oriental’ peoples of the Middle East were largely detached from the region’s ancient populations, whose appearance in biblical and classical texts looked to make them European by default. It seemed evident, therefore, that they ‘belonged’ to the West, as did their monuments and artefacts.5 Backed by military and economic muscle, the European powers harvested the remains of the past, colonizing antiquity as much as they did the living communities of the region. Indeed, a recurring theme of this book is warfare and ownership. Conflict in the Middle East brought Europeans to the region, first as mercenaries and military advisers, and then as invading armies. The colonial soldiers were preceded, joined and followed by scholars of antiquity, interested in answering questions initially constructed around ideas of race. As the evidence for the Sumerians was unearthed and deciphered it became closely woven into narratives about the origins of Western civilization. While empires and ideologies were pitted against each other, often in bloody wars of unimaginable ferocity, through much of the twentieth century, a reassuring picture of the Sumerians emerged as a peaceful people responsible for the invention of nothing less than cities, writing and the wheel; they could even be credited with experiments in democracy. Indeed, in 1963 Samuel Kramer, an eminent scholar of Sumerian language and texts, felt confident in describing an ancient people

remarkable not only for their material progress and technological resourcefulness, but also for their idea, ideals, and values. Clear-sighted, level headed, they took a pragmatic view of life and, within the limits of their intellectual resources, rarely confused fact with fancy, wish with fulfilment, or mystery with mystification.6

Kramer might as well have been describing the best of his own liberal arts students at the University of Pennsylvania. Even when the language used to describe the Sumerians is less extravagant, the role of a peaceful and learned people as the ultimate source of fundamental features of modern life remains attractive and popular. In his search for the origins of Western civilization in 2010, for example, the historian Richard Miles found the answer some 6,000 years ago, ‘when the heads of several different [Sumerian] family groups resolved that their chances of a prosperous and secure future would be enhanced if they worked together as a more or less permanent collective’.7 In this way, ‘while most of the rest of humankind struggled to progress beyond simple agricultural techniques, the Sumerian people, all across the flat plains of southern Mesopotamia, were enjoying many of the benefits and trappings of a civilized urban life.’8

The Sumerians are understood today, therefore, as a distinct people, speaking a common language and sharing a common culture, who occupied the region of southern Iraq in approximately 3500–2000 BC. It was there, in the world’s first cities, that they created the earliest civilization, inventing writing and developing sophisticated systems of governance, architecture, agriculture, astronomy and mathematics. These Sumerian achievements established the foundations of successive Mesopotamian civilizations, influenced the societies of the wider Middle East, and lie at the root of our own urban, literate world.

‘Sumerians’ from the Seventh International Sand Sculpture Festival in Pêra, Portugal, 2009.

This book is an account of how we have come to understand the Sumerians as much as an introduction to their history and culture. The Sumerians were never simply lost and found, but they have been reinvented a number of times, both in antiquity and in the more recent past. To some extent this is a story of ancient and modern myth-making. We now understand that there is no such thing as an accurate representation of the past, but instead only successive approaches, inevitably influenced by our own cultural roots and biases. By exploring how the Sumerians have been constructed by archaeologists, art historians and philologists (among many others) over the past 150 years, it is possible to consider what we think we know, how we know it and also why we should care.

Before starting that journey, a few words about terminology. I hope the reasons why we use the terms ‘Sumerians’ and ‘Sumer’ will become clear in the coming pages, but the name Mesopotamia needs an explanation at the beginning. It is a Greek term meaning ‘between rivers’, first used by geographers in the Hellenistic period, that is from around the third century BC, to describe an area bordered by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. The word and its definition were adopted by Western writers from the Renaissance onwards. In Arabic accounts, however, the term al-’Iraq (the shore of a river and associated grazing land) had been used since at least the eighth century for the vast alluvial plains south of Baghdad.9 This southern region is sometimes referred to as Babylonia by historians and archaeologists. In this book I will follow the conventional use of the name Mesopotamia when describing the region from antiquity until the 1920s, after which it becomes more appropriate to refer to the modern countries of Iraq and Syria.

East meets West

In looking for a beginning to our story, a good place to start is not, as might be expected, on the lowlands of Iraq but instead further east in the highlands of Iran during the time of one of its most famous rulers, the Safavid dynasty emperor Shah ‘Abbas I (r. 1588–1629).

When Shah ‘Abbas inherited the throne of Persia, the country was in a perilous state. The Turkish Ottoman Empire dominated the Caucasus as far south as Tabriz, as well as Mesopotamia to the west. Indeed, much of western Iran was under threat from Turkish forces, and in 1590 the region was actually lost to them. It was little better to the southwest, where the Portuguese Empire...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chronology

- 1 Origins

- 2 The Sumerian Problem

- 3 Invasion, Occupation and Ownership

- 4 The First Cities

- 5 The First Writing

- 6 Back to the Beginning

- References

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Acknowledgements

- Index

Normes de citation pour The Sumerians

APA 6 Citation

Collins, P. (2021). The Sumerians ([edition unavailable]). Reaktion Books. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2372115/the-sumerians-lost-civilizations-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

Collins, Paul. (2021) 2021. The Sumerians. [Edition unavailable]. Reaktion Books. https://www.perlego.com/book/2372115/the-sumerians-lost-civilizations-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Collins, P. (2021) The Sumerians. [edition unavailable]. Reaktion Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2372115/the-sumerians-lost-civilizations-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Collins, Paul. The Sumerians. [edition unavailable]. Reaktion Books, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.