![]()

PART I

HISTORY AND CONTEXT

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Larger Calling

The Field of Integral Studies

At any moment, half of the globe, animals and humans included, is engaged in sleeping and dreaming. As the Earth's rotation in space brings about the night, sleep and dreaming slowly pass from one time zone to the next. Given that dreams are such an important part of our life, a simple question lies at the heart of this book: How do dreams participate in our process of becoming the whole of who we are? To try to answer this question we turn to the concept of integralism.

The integral paradigm is still emerging, stimulated by a growing need to make sense of the interconnectedness of the various dimensions of our life, from the cellular to the individual, and all the way to global living systems. In this chapter we explore briefly the context and history of integral philosophy (see also McIntosh, 2007) and some of its applications within psychology.

THE INTEGRAL MEME: THREE MAIN STREAMS

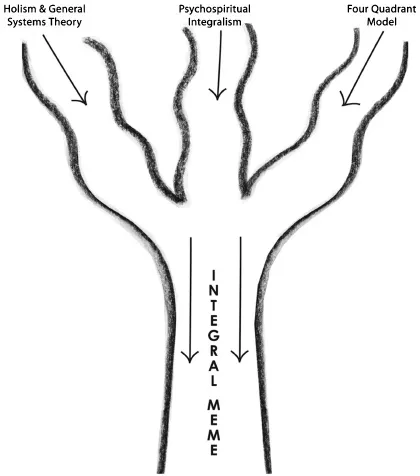

We have identified three main streams of thought woven into the meaning of the term integral (see figure 1). The first stream is holism and general systems theory. Holism derives from the insight that both the forms in nature and organization within human cultures became progressively more complex with time and evolution. This insight has fueled an interdisciplinary focus in life and social sciences that has stimulated development of a general systems theory and the science of complexity. The influences and applications of these lines of thought have reached many other fields, including psychology.

FIGURE 1. THE THREE STREAMS OF INTEGRAL.

The second stream is integralism, a term used in the psychospiritual context. Founded within philosophy and psychology, integralism focuses on the development of the whole person with a view toward unfolding its fullest potential, at both an individual and collective level.

The third stream speaks of integralism within an epistemological context. This view takes into account the fact that different types of human expertise are connected to different ways of acquiring knowledge. These diverse areas of knowledge often compete in claiming the best forms of truth. When viewed from an integral perspective, however, their inherent complementarity becomes more apparent.

This book arises at the confluence of these three streams as we attempt to integrate them into an expanded understanding. Although these streams of ideas have their origins in the premodern era, their current configuration started to take shape in the early twentieth century and matured into the work of several authors at the end the century. By now, the integral meme (understood as a self-reproducing idea that informs the behaviors and beliefs of individuals and groups) is playing out in the global cultural sphere. An integral movement is emerging whose cultural importance is still cresting. What follows is an introduction to each of these three streams that anchor the foundation of our inquiry.

THE FIRST STREAM: HOLISM AND GENERAL SYSTEMS THEORY

The idea of integral conveys comprehensiveness, or the search for an all-inclusive model that helps us find and understand the diverse contributions and recognizable patterns in the workings of the universe and human consciousness. In particular, it relates to the general idea of holism, or nondual thinking, resists any kind of oppositional thinking, and avoids reducing a complex system to the sum of its parts by valuing the creative synergy that is present in any whole.

Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza introduced the idea of holism (1963/1677) in the seventeenth century in opposition to reductionism and in reaction to Descartes' mind-body dualism (Bennett, 1984; Della Rocca, 1996; Koistinen & Biro, 2002). Cognizant of Spinoza and his dialectics, the eighteenth-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) used the idea of unity also as a form of anti-reductionism.1 “The ‘reality’ to Hegel is only in the ‘whole,’ and nothing less than whole is real” (Razali, 2003). Hegel's dialectic idealism has had a broad influence in social philosophy across many systems including existentialism and socialism.

However, the actual word holism was proposed by South African philosopher Jan Smuts in his book Holism and Evolution (1926). He defines holism as follows:

[Holism is] the ultimate synthetic, ordering, organizing, regulative activity in the universe which accounts for all the structural groupings and syntheses in it, from the atom and physico-chemical structures, through the cell and organisms, through Mind in animals, to Personality in man. The all-pervading and ever increasing character of synthetic unity or wholeness in these structures leads to the concept of Holism as the fundamental activity underlying and co-ordinating [sic] all others, and to the view of the universe as a Holistic Universe. (317)

An alternative formulation of the same idea is that of a system, defined as a set of interacting or interdependent entities forming an integrated whole. From the 1930s through the 1950s, in particular with the work of Austrian biologist Karl Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1951), a creative explosion led to the development of a general systems theory with applications in many fields, including ecology, cybernetics, psychology, medicine, anthropology, and organizational theory.

From a general systems perspective, phenomena can be viewed as a web of relationships. All systems—whether informational, biological, or social—share common patterns, behaviors, and properties. Understanding these patterns brings insight into complex phenomena. As physicist Fritjof Capra explains, “There is something else to life, something nonmaterial and irreducible—a pattern of organization” (Capra, 1996: 81). Capra continues, the “pattern of life, we might say, is a network pattern capable of self-organization” (83). Systems theory has enabled a dialogue toward a unity of science. One of the most prevalent examples today is seen in the field of health care with the movement toward holistic medicine. Such an approach fosters practices that deal with health problems in their many dimensions—physical, psychological, social, cultural, and existential (spiritual)—and in which different preventive and healing modalities are used in an integrative manner.

Applied to human life and evolution, the core idea of systems theory is that humans are open systems. We participate in and are influenced by many other systems simultaneously. Human life is coextensive with nature (our biology), nurture (our unique developmental journey), and culture (our cultural matrix). For example, our brain reflects our biological and hereditary origins and autonomous programs (one of which is the sleep-wake cycle), but it is also connected to our cognitive-emotional functions that accumulate experience and developmentally make sense of it. In addition, through language and other creative forms (in particular the arts and technology), an extended social consciousness connects our personal awareness to larger social and cultural processes.

Holistic models consider the mind not as a simple property that emerged from the evolution of a more complex brain but as the site of a dynamic interplay among many levels and scales of a complex system. These are characterized by the presence of multiple interacting components whose connections, far from being fixed, vary dynamically. For example, within the human personality, we could speak of conscious awareness flowing through not only our bodily self, but also our emotional self, our relational/intersubjective self, our intellectual self (cognition), and our spiritual self (morality, faith). Each of these elements dynamically coalesces with the others to give rise to experience at the fluid border between inner and outer life. Within this holistic view, we bring dream studies as an essential phenomenon of the mind.

Holism and general systems theory arose within the context of the secular humanism of the Enlightenment, where spiritual concerns are confined to personal beliefs and choice. Because of this historical limitation, the theory tends to fall short in one serious way, as Ken Wilber (1995) has pointed out: holism seems overly reliant on “horizontal” (material) explanations and leaves out the aspects that would give it “vertical” (existential or spiritual) depth. The second stream addresses this lack from a profoundly radical perspective.

THE SECOND STREAM: INTEGRALISM IN THE PSYCHOSPIRITUAL CONTEXT

The second stream informing the meaning of integralism connects the insights of complexity, dynamism, and evolution to a deeper, larger, and more encompassing ground. This stream is rooted in the integral philosophy and lifework of Indian philosopher Aurobindo Ghose (known as Sri Aurobindo) early in the twentieth century (Aurobindo, 1970). It was further developed by Haridas Chaudhuri (1965, 1974, 1977) and later on by Ken Wilber (2000). Their views assert that the material universe (the preoccupation of science) unfolds as an expression of a boundless spirit, and evolution is seen as an intelligent process that relies on our conscious human participation—a view that is absent in the purely material rendition of holism.

Integralism originated in the philosophy of purna (full, complete, integral) yoga (meaning to unite or bind), translated as “integral yoga,” a practice that points toward an integration among the material, psychological, and spiritual spheres of knowledge and being. “For integral yoga the ultimate goal of life is complete self-integration” (Chaudhuri, 1965: 77). This philosophy also considers the evolution of consciousness, both individual and collective, as one of its central concerns.

Sri Aurobindo, a philosopher and yoga practitioner, was born in India in 1872, educated in England, and developed his philosophical ideas out of several Western and Eastern philosophical thought systems. When he returned to India at the turn of the twentieth century, he became embroiled in the fight for India's independence. While a political prisoner, he underwent a profound spiritual opening. Being familiar with both Eastern and Western traditions at a time when the colonial era was coming to an end, his thinking expressed a form of cultural integration that was unprecedented and contained keen foresight of the global awareness that would emerge decades later.

Aurobindo was familiar with the philosophy of Kant and Hegel and the evolutionary theory of Darwin and Spencer. Philosopher Steve Odin (1981) states that Hegel appropriates Kant's “impersonal unity of self-consciousness” and develops his metaphysical system of “universal consciousness” or “Absolute Spirit.” Within the Eastern system of Indian philosophy, Aurobindo relied on Vedanta (a set of philosophical traditions, based on the Hindu Vedas and concerned with the self-realization by which one understands the ultimate nature of reality or Brahman) and the complex spiritual system known as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Aurobindo attempts to create a synthesis among these different East-West philosophical systems.

In The Meeting of the East and the West in Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy, Indian scholar S. K. Maitra (1968) shows the commonality and differences between Hegel and Aurobindo in their views of spiritual evolution. Aurobindo disagreed with Hegel in identifying Spirit with Reason. Maitra views Aurobindo's evolutionary philosophy as a “new idea, which is not found in any system, either ancient or modern.” Maitra goes on:

This is the idea of integration. Evolution is not merely an ascent from a lower to a higher state. It is also an integration of the higher with the lower ones. This means when a higher principle emerges, it descends into the lower ones causing a transformation of them. Thus when Mind emerges, not only does a new principle appear on the scene, but the lower principles of matter and life also undergo a transformation, so that they become different from what they were before the emergence of this new principle. (38–39)

Aurobindo's evolutionary model considers spiritual nature as an important aspect of an integral view. Chaudhuri and Spiegelberg (1960) state that Aurobindo's philosophy is “integral nondualism.” Aurobindo acknowledges that Eastern philosophy in general promotes the idea of nondualism, which is “an intuitive approach to life and existence—an approach which seeks to understand reality in its undivided wholeness and fundamental oneness” (19).

Originally, non-Western approaches to an integral philosophy meant almost exclusively “Eastern” approaches.2 Since then, the integral approach has grown to encompass other wisdom traditions, including mystical and indigenous or Earth-based spirituality as well as insights from new spiritual movements, such as that sparked by Aurobindo himself. Chaudhuri and Spiegelberg offer an interpretation of the concept of integral nondualism within Aurobindo's philosophy: “Integral nondualism integrates the significant distinctions of ethics, religion, logic and metaphysics in its nondualistic philosophical outlook, without deprecating their value and importance. It reconciles the dualities of thought and existence in the unity of integral experience, integral living, and the integral sweep of cosmic evolution” (19).

The integral concept has also been applied within the field of psychology. For some, it relates principally to the psychology derived from the integral philosophy of Aurobindo (e.g., Sen, 1986; Cor...