Symmetrizing Syntax

Merge, Minimality, and Equilibria

Hiroki Narita, Naoki Fukui

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

Symmetrizing Syntax

Merge, Minimality, and Equilibria

Hiroki Narita, Naoki Fukui

À propos de ce livre

Symmetrizing Syntax seeks to establish a minimal and natural characterization of the structure of human language (syntax), simplifying many facets of it that have been redundantly or asymmetrically formulated.

Virtually all past theories of natural language syntax, from the traditional X-bar theory to the contemporary system of Merge and labeling, stipulate that every phrase structure is "asymmetrically" organized, so that one of its elements is always marked as primary/dominant over the others, or each and every phrase is labeled by a designated lexical element. The two authors call this traditional stipulation into question and hypothesize, instead, that linguistic derivations are essentially driven by the need to reduce asymmetry and generate symmetric structures. Various linguistic notions such as Merge, cyclic derivation by phase, feature-checking, morphological agreement, labeling, movement, and criterial freezing, as well as parametric differences among languages like English and Japanese, and so on, are all shown to follow from a particular notion of structural symmetry. These results constitute novel support for the contemporary thesis that human language is essentially an instance of a physical/biological object, and its design is governed by the laws of nature, at the core of which lies the fundamental principle of symmetry.

Providing insights into new technical concepts in syntax, the volume is written for academics in linguistics but will also be accessible to linguistics students seeking an introduction to syntax.

Foire aux questions

Informations

1

Symmetry of Merge

Why only Merge?

1.1 Introduction

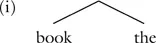

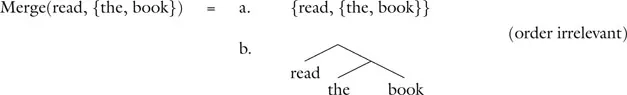

- (1) Merge(Σ1, …, Σn) = {Σ1, …, Σn}

| Question 1: | Why only Merge?—Why do linguists, Berwick and Chomsky, among others, want to claim that it is Merge that instantiates the only distinctive property of human language? What is supposed to be the empirical gain from this proposal? |

| Question 2: | Why only Merge?—Why do they want to claim that Merge is the only species-specific property, disregarding other cognitive capacities of human beings, which may or may not be as innate, innovative, and/or specific? |

| Question 3: | Why only Merge?—Why is it only Merge, and not any other devices, that has the properties it does and that was allowed to emerge by virtue of the evolution-development of human beings? That is, why is Merge as it is rather than any other way? |

1.2 Only Merge, because it is minimally necessary to capture the Basic Property of human language

- (2)

- the boy (often) (eagerly) read the book (carefully) (quickly) (at the station) (at 2pm) (last week) …

- the (smart) (young) (handsome) … boy (who was twelve years old) (who Mary liked) (whose mother was sick) … read the book.

- (3)

- the boy read the book (and/or/but) the girl drank coffee (and/or/but) …

- [the boy (and/or/but not) the girl (and/or) …] read the book.

- (4)

- I know that [the girl believes that [it is certain that … [the boy read the book] …]]

- The boy [(that/who) the girl [(that/who) the cat […] bit] liked] read the book.

- (5)

- (6)

- (i) For any SO K, (a) K is a term of K, and (b) if L is a term of K, then the members of the members of L are terms of K.

Table des matières

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- Preface Page

- 1 Symmetry of Merge: why only Merge?

- 2 Symmetry of phases: Cyclic Transfer and feature-equilibrium

- 3 Symmetry of agreement: Reducing Multiple Agree(ment) mechanisms into feature-equilibrium

- 4 Symmetry of labeling: beyond Chomsky’s Labeling Algorithm and universal/unique labeling condition

- 5 Symmetry of movement: criteria, freezing, and cyclicity

- 6 Conclusions

- References

- Appendix C List of propositions

- Index