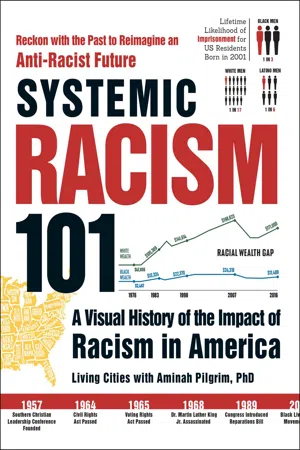

Systemic Racism 101

A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in America

Living Cities, Aminah Pilgrim

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

Systemic Racism 101

A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in America

Living Cities, Aminah Pilgrim

À propos de ce livre

Discover how—and why—Black, Indigenous, and people of color in America experience societal, economic, and infrastructural inequality throughout history covering everything from Columbus's arrival in 1492 to the War on Drugs to the Black Lives Matter movement. From reparations to the prison industrial complex and redlining, there are a lot of high-level concepts to systemic racism that are hard to digest. At a time where everyone is inundated with information on structural racism, it can be hard to know where to start or how to visualize the disenfranchisement of BIPOC Americans.In Systemic Racism 101, you will find infographic spreads alongside explanatory text to help you visualize and truly understand societal, economic, and structural racism—along with what we can do to change it. Starting from the discovery of America in 1492, through the Civil Rights movement, all the way to the criminal justice reform today, this book has everything you need to know about the continued fight for equality.

Foire aux questions

Informations

CHAPTER ONE 1492 TO THE CIVIL WAR

- 1400s: African civilizations thrive; age of European exploration

- 1492: Arrival of Columbus in the Americas begins settler colonialism; ongoing violence against Indigenous populations; early encounters give way to racial ideology

- 1500s: Religious doctrines and laws shape attitudes and practices between “races”; the word race first appears in the English language

- 1600s: Free people of African descent in the colonies, predating Jamestown

- 1619: First twenty enslaved people forcibly brought to Jamestown, Virginia

- 1662: Virginia enacts a law that makes enslavement a life sentence tied to Black women’s bodies by making slavery hereditary

- 1675–1676: Bacon’s Rebellion, a cross-class and mixed-race rebellion

- 1775–1783: American Revolution and United States Declaration of Independence from the British (1776)

- 1791–1804: Haitian Revolution

- 1780s: “Queen” sugar (sugar cultivated by the enslaved) is the global “white gold”

- 1794: Eli Whitney patents the cotton gin, making cotton “king” of cash crops

- 1800–1865: Height of the Underground Railroad; Harriet Tubman is one of its most well-known conductors

- 1807: British government abolishes the transatlantic slave trade throughout its territories; US slavery continues to grow

- 1831: Hanging of Nat Turner, leader of one of the most powerful US slave revolts

- 1850s: Resistance to slavery and calls for abolition intensify

- 1852: Harriet Beecher Stowe publishes Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- 1859: Harpers Ferry raid; midcentury tensions over slavery between Northern and Southern states

- 1861–1865: American Civil War

EUROPEANS EXPLOIT WESTERN AFRICA

WHAT AFRICA WAS LIKE IN THE 1400S AND 1500S

- • Family was the central building block of these collectivist societies.

- • Land ownership and governance were passed through kinship lines (both patrilineal and matrilineal).

- • Slavery existed there before European contact. The slavery that existed among them was a result of war and was no life sentence; it was a source of wealth building for the slaveholding clans as enslaved people often worked to earn release from punishments. Female “slaves” may have been used as concubines. In most cases, this kind of slavery did not involve hard physical labor.

THE ORIGINS OF COLONIZERS’ PERCEIVED SUPERIORITY

THE FALLACY OF THE “NEW” WORLD

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title Page

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter One: 1492 to the Civil War

- Chapter Two: Reconstruction and Jim Crow

- Chapter Three: The Civil Rights Movement

- Chapter Four: 1970s–2008

- Chapter Five: 2008–Present

- Resources and Further Reading

- Data Sources for Infographics

- Image Sources for Infographics

- About the Author Team

- Index

- Copyright