eBook - ePub

C. S. Lewis: A Life

Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet

Alister E McGrath

This is a test

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

C. S. Lewis: A Life

Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet

Alister E McGrath

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The recent Narnia films have inspired a resurgence of interest in C. S. Lewis, the Oxford academic, popular theologian and, most famously, creator of the magical world of Narnia - and this authoritative new biography, published to mark the 50th anniversary of Lewis's death, sets out to introduce him to a new generation. Completely up to date with scholarly studies of Lewis, it also focuses on how Lewis came to write the Narnia books, and why they have proved so consistently engaging. Accessible and engaging, this new biography will appeal to fans of the films, readers of Lewis and of theologian and apologist Alister McGrath himself.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que C. S. Lewis: A Life est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à C. S. Lewis: A Life par Alister E McGrath en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Theology & Religion et Religious Biographies. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Theology & ReligionSous-sujet

Religious BiographiesPart 1

Prelude

Chapter 1 | 1898–1908

The Soft Hills of Down: An Irish Childhood

“I was born in the winter of 1898 at Belfast, the son of a solicitor and of a clergyman’s daughter.”1 On 29 November 1898, Clive Staples Lewis was plunged into a world that was simmering with political and social resentment and clamouring for change. The partition of Ireland into Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was still two decades away. Yet the tensions that would lead to this artificial political division of the island were obvious to all. Lewis was born into the heart of the Protestant establishment of Ireland (the “Ascendancy”) at a time when every one of its aspects—political, social, religious, and cultural—was under threat.

Ireland was colonised by English and Scottish settlers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, leading to deep political and social resentment on the part of the dispossessed native Irish towards the incomers. The Protestant colonists were linguistically and religiously distinct from the native Catholic Irish. Under Oliver Cromwell, “Protestant plantations” developed during the seventeenth century—English Protestant islands in an Irish Catholic sea. The native Irish ruling classes were quickly displaced by a new Protestant establishment. The 1800 Act of Union saw Ireland become part of the United Kingdom, ruled directly from London. Despite being a numerical minority, located primarily in the northern counties of Down and Antrim, including the industrial city of Belfast, Protestants dominated the cultural, economic, and political life of Ireland.

Yet all this was about to change. In the 1880s, Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891) and others began to agitate for “Home Rule” for Ireland. In the 1890s, Irish nationalism began to gain momentum, creating a sense of Irish cultural identity that gave new energy to the Home Rule movement. This was strongly shaped by Catholicism, and was vigorously opposed to all forms of English influence in Ireland, including games such as rugby and cricket. More significantly, it came to consider the English language as an agent of cultural oppression. In 1893 the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was founded to promote the study and use of the Irish language. Once more, this was seen as an assertion of Irish identity over and against what were increasingly regarded as alien English cultural norms.

As demands for Home Rule for Ireland became increasingly forceful and credible, many Protestants felt threatened, fearing the erosion of privilege and the possibility of civil strife. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Protestant community in Belfast in the early 1900s was strongly insular, avoiding social and professional contact with their Catholic neighbours wherever possible. (C. S. Lewis’s older brother, Warren [“Warnie”], later recalled that he never spoke to a Catholic from his own social background until he entered the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1914.)2 Catholicism was “the Other”—something that was strange, incomprehensible, and above all threatening. Lewis absorbed such hostility towards—and isolation from—Catholicism with his mother’s milk. When the young Lewis was being toilet trained, his Protestant nanny used to call his stools “wee popes.” Many regarded, and still regard, Lewis as lying outside the pale of true Irish cultural identity on account of his Ulster Protestant roots.

The Lewis Family

The 1901 Census of Ireland recorded the names of everyone who “slept or abode” at the Lewis household in East Belfast on the night of Sunday, 31 March 1901. The record included a mass of personal details—relationship to one another, religion, level of education, age, sex, rank or occupation, and place of birth. Although most biographies refer to the Lewis household as then residing at “47 Dundela Avenue,” the Census records them as living at “House 21 in Dundella [sic] Avenue (Victoria, Down).” The entry for the Lewis household provides an accurate snapshot of the family at the opening of the twentieth century:

Albert James Lewis, Head of Family, Church of Ireland, Read & Write, 37, M, Solicitor, Married, City of Cork

Florence Augusta Lewis, Wife, Church of Ireland, Read & Write, 38, F, Married, County Cork

Warren Hamilton Lewis, Son, Church of Ireland, Read, 5, M, Scholar, City of Belfast

Clive Staples Lewis, Son, Church of Ireland, Cannot Read, 2, M, City of Belfast

Martha Barber, Servant, Presbyterian, Read & Write, 28, F, Nurse—Domestic Servant, Not Married, County Monaghan

Sarah Ann Conlon, Servant, Roman Catholic, Read & Write, 22, F, Cook—Domestic Servant, Not Married, County Down3

As the Census entry indicates, Lewis’s father, Albert James Lewis (1863–1929), was born in the city and county of Cork, in the south of Ireland. Lewis’s paternal grandfather, Richard Lewis, was a Welsh boilermaker who had immigrated to Cork with his Liverpudlian wife in the early 1850s. Soon after Albert’s birth, the Lewis family moved to the northern industrial city of Belfast, so that Richard could go into partnership with John H. MacIlwaine to form the successful firm MacIlwaine, Lewis & Co., Engineers and Iron Ship Builders. Perhaps the most interesting ship to be built by this small company was the original Titanic—a small steel freight steamer built in 1888, weighing a mere 1,608 tons.4

Yet the Belfast shipbuilding industry was undergoing change in the 1880s, with the larger yards of Harland and Wolff and Workman Clark achieving commercial dominance. It became increasingly difficult for the “wee yards” to survive economically. In 1894, Workman Clark took over MacIlwaine, Lewis & Co. The rather more famous version of the Titanic—also built in Belfast—was launched in 1911 from the shipyard of Harland and Wolff, weighing 26,000 tons. Yet while Harland and Wolff’s liner famously sank on its maiden voyage in 1912, MacIlwaine and Lewis’s much smaller ship continued to ply its trade in South American waters under other names until 1928.

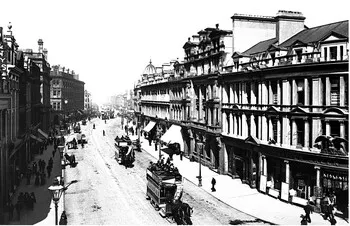

1.1 Royal Avenue, one of the commercial hubs of the city of Belfast, in 1897. Albert Lewis established his solicitor’s practice at 83 Royal Avenue in 1884, and continued working from these offices until his final illness in 1929.

Albert showed little interest in the shipbuilding business, and made it clear to his parents that he wanted to pursue a legal career. Richard Lewis, knowing of the excellent reputation of Lurgan College under its headmaster, William Thompson Kirkpatrick (1848–1921), decided to enrol Albert there as a boarding pupil.5 Albert formed a lasting impression of Kirkpatrick’s teaching skills during his year there. After Albert graduated in 1880, he moved to Dublin, the capital city of Ireland, where he worked for five years for the firm of Maclean, Boyle, and Maclean. Having gained the necessary experience and professional accreditation as a solicitor, he moved back to Belfast in 1884 to establish his own practice with offices on Belfast’s prestigious Royal Avenue.

The Supreme Court of Judicature (Ireland) Act of 1877 followed the English practice of making a clear distinction between the legal role of “solicitors” and “barristers,” so that aspiring Irish lawyers were required to decide which professional position they wished to pursue. Albert Lewis chose to become a solicitor, acting directly on behalf of clients, including representing them in the lower courts. A barrister specialised in courtroom advocacy, and would be hired by a solicitor to represent a client in the higher courts.6

Lewis’s mother, Florence (“Flora”) Augusta Lewis (1862–1908), was born in Queenstown (now Cobh), County Cork. Lewis’s maternal grandfather, Thomas Hamilton (1826–1905), was a Church of Ireland clergyman—a classic representative of the Protestant Ascendancy that came under threat as Irish nationalism became an increasingly significant and cultural force in the early twentieth century. The Church of Ireland had been the established church throughout Ireland, despite being a minority faith in at least twenty-two of the twenty-six Irish counties. When Flora was eight, her father accepted the post of chaplain to Holy Trinity Church in Rome, where the family lived from 1870 to 1874.

In 1874, Thomas Hamilton returned to Ireland to take up the position of curate-in-charge of Dundela Church in the Ballyhackamore area of East Belfast. The same temporary building served as a church on Sundays and a school during weekdays. It soon became clear that a more permanent arrangement was required. Work soon began on a new, purpose-built church, designed by the famous English ecclesiastical architect William Butterfield. Hamilton was installed as rector of the newly built parish church of St. Mark’s, Dundela, in May 1879.

Irish historians now regularly point to Flora Hamilton as illustrating the increasingly significant role of women in Irish academic and cultural life in the final quarter of the nineteenth century.7 She was enrolled as a day pupil at the Methodist College, Belfast—an all-boys school, founded in 1865, at which “Ladies’ Classes” had been established in response to popular demand in 1869.8 She attended for one term in 1881, and went on to study at the Royal University of Ireland in Belfast (now Queen’s University, Belfast), gaining First Class Honours in Logic and Second Class Honours in Mathematics in 1886.9 (As will become clear, Lewis failed to inherit anything of his mother’s gift for mathematics.)

When Albert Lewis began to attend St. Mark’s, Dundela, his eye was caught by the rector’s daughter. Slowly but surely, Flora appears to have been drawn to Albert, partly on account of his obvious literary interests. Albert had joined the Belmont Literary Society in 1881, and was soon considered one of its best speakers. His reputation as a man of literary inclinations would remain with him for the rest of his life. In 1921, at the height of Albert Lewis’s career as a solicitor, Ireland’s Saturday Night newspaper featured him in a cartoon. Dressed in the garb of a court solicitor of the period, he is depicted as holding a mortarboard under one arm and a volume of English literature under the other. Years later, Albert Lewis’s obituary in the Belfast Telegraph described him as a “well read and erudite man,” noted for literary allusions in his presentations in court, and who “found his chief recreation away from the courts of law in reading.”10

After a suitably decorous and extended courtship, Albert and Flora were married on 29 A...