![]()

Chapter 1

Acceleration: Jump-Starting Students Who Are Behind

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I recently came into a freshman remedial class to find students busily logging in to the school's basic-skills software. Those who were deemed the furthest behind, according to a diagnostic pre-test, practiced skills that were the furthest removed from the current curriculum. Students who weren't as far behind worked on skills from the previous year or two. Any connection between the skills the students practiced and the standards being introduced in their "regular" classes that same day was entirely coincidental. A young woman rolled her eyes at me as she entered her password on the keyboard: "We've been doing this program since 4th grade."

Hours away in a middle school classroom, bored students identified as requiring remedial interventions sat passively with their workbooks, practicing missing skills, while the higher-achieving students next door engaged collaboratively in hands-on, rigorous exploration aimed at a specific learning goal.

The traditional remedial approaches used in these and countless other classrooms focus on drilling isolated skills that bear little resemblance to current curriculum. Year after year, the same students are enrolled in remedial classes, and year after year, the academic gaps don't narrow. And no wonder: instead of addressing gaps in the context of new learning and helping students succeed in class today, remedial programs largely engage students in activities that connect to standards from years ago. Rather than build students' academic futures, remediation pounds away at the past. We spend significant amounts of time teaching in reverse, and then ask why students are not catching up to their peers.

This chapter provides thoughtful answers to a pressing question: how can we help students with gaps from the past succeed today? You will learn to provide a different, more effective type of support for struggling students that will yield immediate improvement in their academic progress, self-confidence, perseverance, and grades and test scores. In addition, you will see higher levels of participation and engagement and fewer incidences of off-task behavior.

Behind on the First Day of School

We know more about underperforming students today than ever before. Expansive color-coded spreadsheets detail every possible gap. Mountains of standardized test data reveal missed items from every subject area. Fractions, multiplication tables, parts of speech, order of operations, decimals, author's purpose, long division, branches of government, reading to infer … the list of things students should know (but don't) is daunting.

On the first day of school, many students are already behind. Marzano (2004) shares a gut-wrenching reality: what students already know when they enter the classroom—before we have even met them—is the strongest predictor of how well they will learn the new curriculum. Concepts, skills, and vocabulary from last semester, last year, and three grades ago can haunt students' efforts to acquire new information.

It works like this. As information is being taught, students' brains try to make sense of new concepts by linking and integrating the incoming barrage of information with prior knowledge. This schema, or individual storage unit of information, plays a critical role in new learning. Vacca and Vacca (2002) explain that when students' brains link background knowledge with new text, students are better at making inferences and retain information more effectively. Hirsch (2003) contends that prior knowledge about a topic speeds up learning by freeing up students' working memory so that they can connect to new information more readily. In short, students with background knowledge on a given topic are likely to grasp new information on that topic quickly and well (Marzano, 2004). Conversely, a lack of adequate prior knowledge can create a misfire in the learning process.

For example, read the following short passage:

Betsy had never tackled the Cement Mixer before. Although many fears cycled through her mind, her two main concerns were handling the backdoor and the lip. Her confidence rose, however, as she reminded herself that if she could just get into the barrel she had a good chance of winning, especially if conditions were cooking. She stared out at the horizon, shook her fist triumphantly in the air, and shouted, "I'm ready for you, Meat Grinder! I can handle the biggest Macker you can deliver!"

Now, in your own words, explain what Betsy is doing. Stumped? Every word is familiar and the reading level is basic, so what's the problem?

As it turns out, Betsy is a surfer. Terms like backdoor, lip, and even Cement Mixer have their own special meanings in the surfing lexicon. Without prior knowledge of Betsy's particular sport, true comprehension of this text is quite difficult. If you lack a schema for surfing, reading this passage would fail to spark a connection between prior knowledge and new information, and the text would be meaningless—and you'd fall behind in class.

The Trouble with Remediation

Just as a lack of background knowledge about surfing would lead to a lack of comprehension of the passage about Betsy, students who have insufficient academic background knowledge tend to have a multitude of missing academic pieces. Remediation, the correction of deficiencies, attempts to fix everything that has gone wrong in students' schooling—to fill in all those missing pieces. Unfortunately, many of those pieces may have nothing to do with what is happening today.

Remediation is based on the misconception that for students to learn new information, they must go back and master everything they missed. So, for example, all of the students who are weak in math—probably determined through a pre-test—are herded together and assigned a teacher who will reteach them basic math skills. The students who have the largest gaps and are thus the most academically vulnerable are sent the furthest distance back.

In the end, this remedial model may produce a student who can finally subtract two fractions; unfortunately, that student may now be a junior in high school. While the rest of her classmates moved forward, she moved backward. Reverse movement at a tedious pace with little relevance to today's standard will not catch students up to their peers. In fact, this model may contribute to widening gaps, as stronger students get even stronger while the weaker ones continue to sink further.

This failure to move forward can lead to decreased student motivation. Aside from the fact that students who have already grown to dislike math now have additional classes in the subject they despise, it's difficult to feel motivated when there's no apparent progress. In addition, remedial courses typically provide a surfeit of passive, basic-skills work and little real-world relevance. Boredom and futility creep in, and students often give up and shut down.

Why Acceleration Works

The primary focus of remediation is mastering concepts of the past. Acceleration, on the other hand, strategically prepares students for success in the present—this week, on this content. Rather than concentrating on a litany of items that students have failed to master, acceleration readies students for new learning. Past concepts and skills are addressed, but always in the purposeful context of future learning.

Acceleration jump-starts underperforming students into learning new concepts before their classmates even begin. Rather than being stuck in the remedial slow lane, students move ahead of everyone into the fast lane of learning. Acceleration provides a fresh academic start for students every week and creates opportunities for struggling students to learn alongside their more successful peers.

As we know, students learn faster and comprehend at a higher level when they have prior knowledge of a given concept. The correlation between academic background knowledge and achievement is staggering: prior knowledge can determine whether a 50th-percentile student sinks to the 25th percentile or rises to the 75th (Marzano, 2004). Accordingly, a crucial aspect of the acceleration model is putting key prior knowledge into place so that students have something to connect new information to. Rather than focus on everything students don't know about the concept, however, the core and acceleration teachers collaboratively and thoughtfully select the specific prior knowledge that will best help students grasp the upcoming standard.

Although the acceleration model does revisit basic skills, these skills are laser-selected, applied right away with the new content, and never taught in isolation. To prepare for a new concept or lesson, students in an acceleration program receive both instruction in prior knowledge and remediation of prerequisite skills that, if missing, may create barriers to the learning process. This strategic approach of preparing for the future while plugging a few critical holes from the past yields strong results.

Closely related to the prior knowledge piece of the acceleration model is vocabulary development. Gaps in prior knowledge are largely related to vocabulary (Marzano, 2004). For example, if you ask a student who has a rich understanding of fractions to write down everything she knows about the topic, she would likely list terms and concepts like improper fraction, denominator, numerator, reciprocal, mixed number, and parts of a whole. Likewise, a student asked to write down everything he knows about government would include terms like bicameral, popular sovereignty, checks and balances, legislature, and federalism. A sizable chunk of these students' prior knowledge consists of academic vocabulary. Therefore, a key step in the acceleration approach is to introduce new vocabulary (and review previously covered critical vocabulary that students may be missing) before the lesson begins in the core class.

Moving forward with students in an acceleration model requires teachers to carefully lay out the pieces of exactly what students need to know to learn the content at the desired pace. Before other students have even begun the unit, the accelerated group has gained an understanding of

- The real-world relevance and purpose of the concept.

- Critical vocabulary, including what the words look and sound like.

- The basic skills needed to master the concept.

- The new skills needed to master the concept.

- The big picture of where instruction is going.

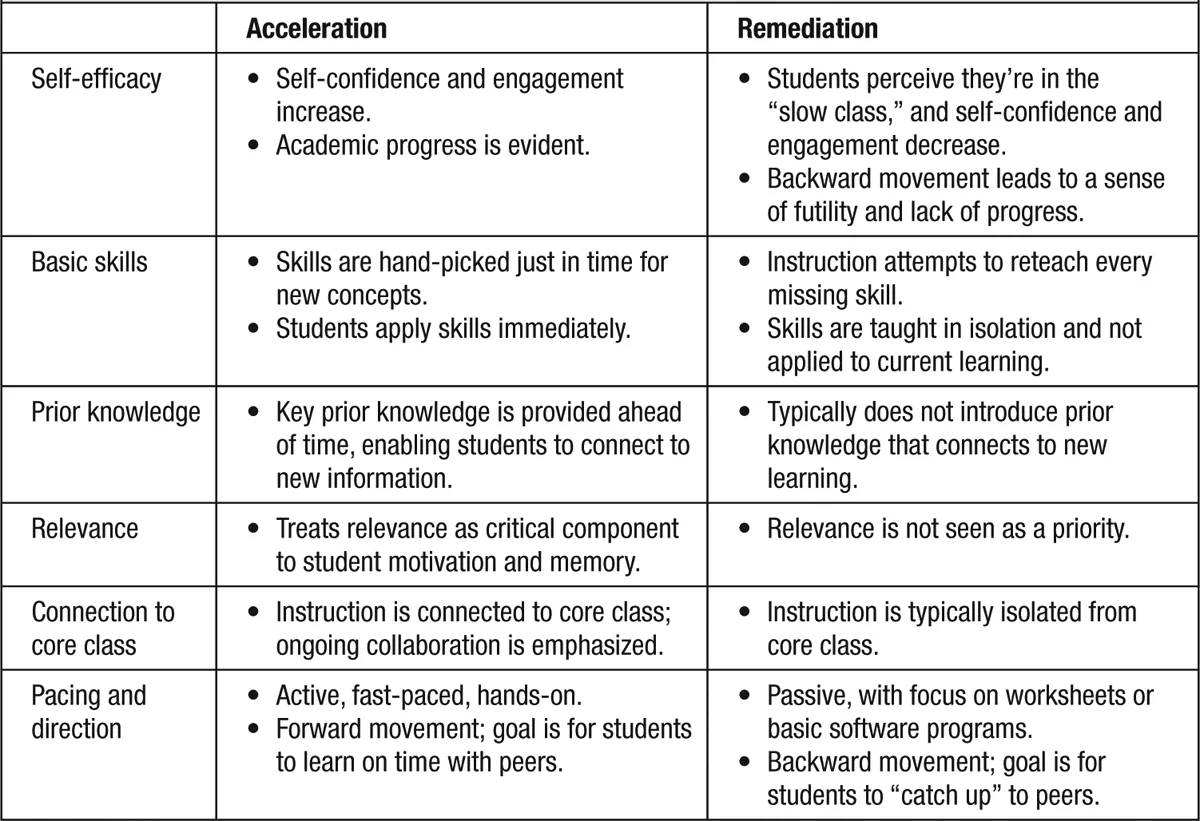

Figure 1.1, which emerged from my work developing acceleration classes with teachers and leaders, presents a comparison of remediation and acceleration.

FIGURE 1.1. Acceleration and Remediation: A Comparison

In my experience helping schools develop acceleration classes, the most common feedback I get from teachers is how quickly student confidence and participation increase. This marked improvement in students' self-efficacy makes perfect sense: concepts are placed directly in students' paths just in time for new learning in their core classrooms. Students' newfound knowledge increases the odds that they will know the correct responses to questions, and suddenly, raising their hands seems safer, and their fear of embarrassment diminishes.

As Sousa and Tomlinson (2011) explain, fear of peer reaction to an incorrect answer is a driving force in students' level of class participation. Conversely, positive feedback from teachers and peers ignites students' desire to keep succeeding. Spikes in self-efficacy, Pajares (2006) found, can lead students to engage more, work harder, stick it out longer, and achieve at higher levels. Students are able to perceive genuine progress, so this increase in self-efficacy is not superficial; it is the brain's response to real success. Acceleration can fuel new hope and motivation in students who once perceived their academic situation as hopeless.

Implementing Acceleration

There are a few logistics to address when implementing an acceleration program. The first step is identifying students who would be good candidates for acceleration, typically by reviewing standardized test data. Some schools focus just on "bubble" students—those who are right on the verge of passing their standardized tests. However, some schools in which I have consulted, after realizing acceleration's potential to yield significant results, expand their acceleration classes to include students with more significant gaps.

Another issue to address is deciding who teaches the acceleration classes. The teachers of acceleration classes may be either students' regular content-area teachers or separate teachers. There are pragmatic reasons to schedule students with their core teachers as much as possible. For example, when students attend acceleration classes with their core teachers, teachers can make just the right instructional moves during acceleration to facilitate student success in the later core class. When a different teacher is used for acceleration, daily communication and coordination of curriculum pacing become essential to maximize the program's effectiveness. The acceleration teacher must know where the core teacher's instruction is to be able to prepare students for success.

Carving out time is another important issue to address when beginning an acceleration program. Some schools schedule a short time (usually around 45 minutes) at the beginning of each day in which all students receive acceleration or enrichment. I've known schools to refer to this time as anything from ELT (Extended Learning Time) to Ram Time (schools can replace Ram with their own mascot) to Fast Lane Class (my favorite).

A second option is to incorporate acceleration into electives, specials, or pullouts. This model often provides more time than the ELT model and is typically used for the "double dose" approach, in which students receive extra instruction in problem subjects. Elementary and middle schools often use an additional teacher for this time, which enables core teachers to use this period for planning. The person in this acceleration role varies by school but is often a special educator or remedial teacher. In high schools, the core teachers often teach their own acceleration classes.

Before- and after-school tutoring or Saturday school is a third option. My first experience with acceleration was through tutoring at the middle school level. I phoned parents and explained to them that this was not going to be traditional tutoring—that our mission was to get their children ahead of the game. Parents were more than willing to make a commitment to ensure their children's attendance. Every day, for 30 minutes before school and 30 minutes after school, I accelerated the group in their trouble courses of math and science. Within a week, core teachers reported significant gains in student participation (one of the key components of success) and achievement. A thrilled science teacher said of one student, "He hasn't made over a 50 on a test all year, and he passed this one with flying colors!"

Students in an acceleration class should always be a session or two ahead of their peers in the core class. On a block schedule, one class period (typically around 90 minutes long) is generally sufficient. If the school is implementing acceleration through shorter tutoring sessions, two sessions are workable for jump-starting the content. These times are just general guidelines; however much time schools are able to set aside can b...