eBook - ePub

From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2

Stress Management and Enhancing Wellbeing

C. Cooper

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2

Stress Management and Enhancing Wellbeing

C. Cooper

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

A comprehensive collection by Professor Cary Cooper and his colleagues in the field of workplace stress and wellbeing, which draws on research in a number of areas including stress-strain relationships, sources of workplace stress and stressful occupations. Volume 2 of 2.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2 est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2 par C. Cooper en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Business et Gestione. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part VI

Stress Management

23

Worksite Stress Management Interventions: Their Effectiveness and Conceptualisation

Richard S. DeFrank and Cary L. Cooper

Introduction

There has been an explosion of interest in the last few years in health promotion or “wellness” programmes. Such activities as exercise, weight control, smoking cessation, stress management and others are being encouraged by virtually every medium available – radio, television, magazines, books and billboards – and are taking place in as wide a variety of settings as well, including homes, parks, churches, schools, facilities for the aged and worksites. Worksites, the focus of this article, have probably shown the most growth regarding their value as locations for delivering health promotion interventions. Among other reasons, this may be due to the consistently available nature of the population in this setting, facilitating regular involvement in health activities. Working people may also be motivated both to maintain and improve their health and have the money to purchase these services, the latter point being especially significant for vendors of health promotion programmes. Additionally, in many cases companies become the consumers of these offerings by purchasing them from outside contractors or by developing in-house programmes for their employees.

These programmes vary considerably on the basis of type of format, facilities required, training of instructors and so on, and in one important area stress management may differ from all other health promotion offerings. The Institute of Medicine’s report on stress and health (Elliott and Eisdorfer, 1982) suggested that organisations provide a major portion of the total stress experienced by a person, due to the amount of time spent on the job, and to the demands for performance and interaction with others made by the organisation. It might then be argued with some success that the workplace has a more direct effect on stress than on such variables as exercise and nutrition (though clearly it will influence these as well), and that stress might have a more negative impact on productivity and satisfaction than that produced by other established risk factors. Of more significance to employers, however, is that they may be held liable for the physical and mental problems of their employees resulting from exposure to job stress. Ivancevich et al. (1985) recently pointed out the growing number of Workmen’s Compensation laws and rulings throughout the USA in favour of the association between stress and injury, disability and the need for medical care. They suggested that managers need to address this issue prior to a suit being brought against their companies. Specifically, managers should evaluate the levels of stress in their organisations, offer programmes to deal with the observed stress and assess programme effectiveness, and document thoroughly what has been done. Thus stress management may become increasingly recognised as a necessary part of corporate personnel policy.

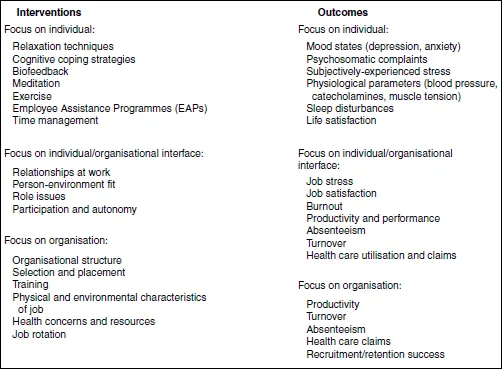

A model of stress management interventions

Given that stress management at the worksite may be a valuable component of a health promotion programme and important in the avoidance of litigation, it follows that the availability of these programmes will continue to increase in the future. It is also apparent that employers, providers and researchers need to broaden their conceptualisation of the focus of stress management interventions and the potential range of outcomes for these programmes. This is necessary because activities aimed solely at individuals’ reactions to stressful circumstances, and not also targetted at modifying the circumstances themselves, will not be sufficient to avoid the negative legal ramifications just discussed. Expanding the focus of enquiry also provides a clearer picture of the phenomena under study, offers more avenues for intervention and evaluation, and improves the chances for behaviour change. An example of this expansion of perspective can be seen in Figure 23.1, which suggests a scheme for viewing the various levels of stress management interventions and outcomes. Three levels are postulated, focusing on the individual, the individual/organisational interface, and the organisation. With regard to interventions, the listing contains those factors which could serve as the target for a stress management intervention programme. These include a set of techniques aimed at the individual, such as relaxation, biofeedback and meditation which target physical concomitants of stress such as muscle tension or blood pressure. Other coping strategies such as cognitive restructuring and time management reflect attempts to alter the ways in which people structure and organise their worlds. Exercise has been noted to improve both physical endurance and mood states, and employee assistance programmes typically provide counselling and referral for employee problems. The individual outcomes that could be used to assess the impacts of these procedures range from the biochemical and physical (e.g. catecholamines, blood pressure, muscle tension) to the psychological (e.g. moods, life satisfaction), with some outcomes in the middle of this range (e.g. psychosomatic complaints such as headaches, nausea, sweating palms, dizziness). This category, in sum, places attention specifically on the person and the ways in which he/she responds to and copes with stress, regardless of the source of stress.

Figure 23.1 Levels of stress management interventions and outcomes

The next level encompasses the interface between the individual and the organisation, emphasising here targets of interventions rather than the techniques themselves, as the latter are not well developed for this kind of interaction. These factors are often cited as major producers of stress in the workplace. For example, conflict among varied roles and ambiguity over the content and responsibilities of these roles may lead to increased job stress and decreased job satisfaction (Fisher and Gitelson, 1983; Van Sell et al., 1981). Similarly, a lack of fit between the objective and subjective characteristics of an environment and the corresponding aspects of an individual may produce significant stress and strain (Caplan, 1983; Harrison, 1985). The outcome variables for this category, as at the individual-focus level, include a range of alternatives. Some are measured by self-report indices such as job stress and satisfaction, and burnout. Other variables are considerably more objective in nature, including absenteeism, turnover and health care claims. Productivity may or may not be included in this latter category, as it may be easy to determine for some workers (e.g. assembly-line workers) and more difficult to estimate for others (e.g. managers).

The third level of interventions and outcomes focuses on the organisation as the target for stress management programming. This list suggests some of the areas in which organisational environment, structure and policies may produce stress for employees. For example, such physical characteristics of the job as excessive heat and noise may produce strain among workers and increase the probability of accidents (Bell and Greene, 1982; Cohen and Weinstein, 1982). Shift schedule, a structural aspect of work, can engender significant levels of physical and mental discomfort if not ordered correctly (Tasto et al., 1978; Zedeck et al., 1983). In addition, policies relating to job training and availability of health care are likely to have an impact on the work performance and satisfaction of employees. A number of the relevant outcomes have been mentioned above, but in this context they are viewed at the organisational rather than the individual level. Also, many of these organisational issues will influence the quality of employees that can be recruited and the ability to retain employees once they are hired.

It should be noted that there is a degree of unavoidable overlap in this ordering, as the levels are not independent of each other. For example, the impact of the physical characteristics of the job will be modified to some extent by the individual’s perception of them. On the other hand, the availability of time to meditate may be a function of environmental demands. Despite these inter-relationships, these three categories of interventions provide a useful classification method that can be applied to outcomes as well. This approach extends our attention to variables that we might not have considered previously as relevant to determining the effect of a stress management programme. However, a broadened range of interventions requires a similarly expanded outcome list, and the impact of a particular intervention should be assessed at a variety of levels to determine its true importance. Note also that overlap occurs quite explicitly among these outcome measures, as productivity, turnover, absenteeism and health care claims all appear twice. These are factors that reflect the interaction between person and environment and also have significant implications for organisational functioning.

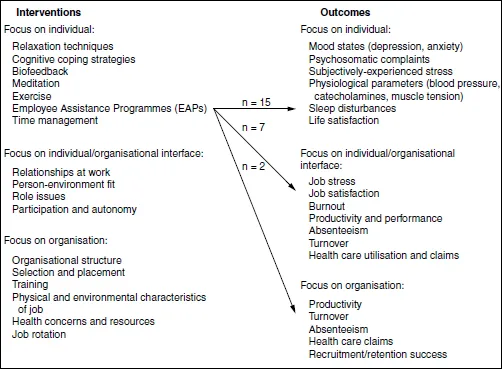

Interventions and outcomes

At this point we might ask how much research has been done linking these interventions and outcomes. The term “research” is used here to denote serious, controlled attempts to evaluate the efficacy of programmes aimed at stress management and reduction and not merely suggestions that such interventions are helpful or anecdotal reports of positive or negative outcomes. Figure 23.2 demonstrates that not many such attempts were found (in actuality, only 18 studies were located, some of which had multiple outcomes), and that all of them examined individual-focus interventions. Further, we see that most of these evaluated individual-level outcomes, with another group focusing on the individual/organisational interface, and a mere two assessing organisational concerns. The lack of research on individual/organisational and organisational programmes should not be surprising, in view of our expanded definition of stress management. While these extra-individual factors have been noted by many authors to be related to work stress, few have developed explicit, testable approaches to dealing with these concerns.

Figure 23.2 Numbers of studies evaluating impact of interventions on outcomes

Newman and Beehr (1979) reviewed both personal and organisational stress management strategies and found that virtually none of the latter had been systematically evaluated. This may be due to the difficulty of gaining sufficient access to an organisation to develop these programmes, as well as to the research as opposed to programmatic orientation of the investigators in this field. In view of the earlier discussion of Workmen’s Compensation cases, and the increased demand for broad-based programmes and their evaluation that is likely to be generated, both of these factors are subject to change. Note also that attention here is placed on the use of organisational issues as the focus of stress management efforts, which is a role that many of these issues have not filled up to now.

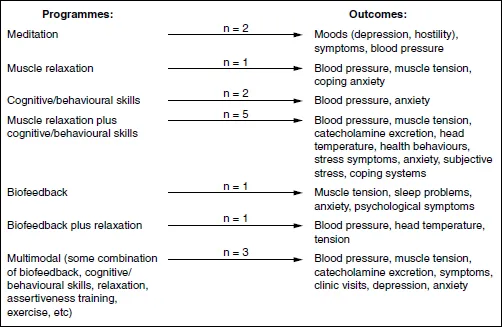

Stress management for the individual

We can break down these general relationships between interventions and outcomes into the more specific pairings seen in Figure 23.3. On the programme side, we see that approaches range from single modalities to two or more treatments in combination. With respect to outcomes, blood pressure and anxiety appear to be the most common measures used, with other psychophysiological, biochemical and psychological variables employed by some of the investigators. Muscle tension appears as an outcome measure most often when muscle relaxation or biofeedback techniques are employed, as might be expected, but no other obvious pairing is evident.

Figure 23.3 Numbers of studies relating specific individual-focus interventions to individual-focus outcomes

Stress management for the organisation

Figure 23.4 focuses on individual/organisational interface outcomes and notes that job satisfaction and job stress measures are most commonly used, but as in Figure 23.3 few discernible patterns of outcomes matched with programmes exist. The two studies in Figure 23.5 note the sole individual programme-organisational outcome linkages.

So far we have looked at what kinds of programmes have been evaluated on what kinds of outcomes, but have not addressed the crucial question as to whether stress management has a positive impact on any of the targetted variables. While time...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title Page

- Part VI Stress Management

- Part VII Stress and Wellbeing issues

- Part VIII Work–Life Balance

- Part IX Wellbeing

- Index

Normes de citation pour From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2013). From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2 ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3483605/from-stress-to-wellbeing-volume-2-stress-management-and-enhancing-wellbeing-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2013) 2013. From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3483605/from-stress-to-wellbeing-volume-2-stress-management-and-enhancing-wellbeing-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2013) From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3483605/from-stress-to-wellbeing-volume-2-stress-management-and-enhancing-wellbeing-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 2. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.