eBook - ePub

Storyboarding

A Critical History

Steven Price, Chris Pallant

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Storyboarding

A Critical History

Steven Price, Chris Pallant

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This study provides the first book-length critical history of storyboarding, from the birth of cinema to the present day and beyond. It discusses the role of storyboarding in key films including Gone with the Wind, Psycho and The Empire Strikes Back, and is illustrated with a wide range of images.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Storyboarding est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Storyboarding par Steven Price, Chris Pallant en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Médias et arts de la scène et Histoire et critique du cinéma. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sous-sujet

Histoire et critique du cinéma1

The Pre-History of Storyboarding

As noted in our introductory chapter, a number of challenges must be negotiated when attempting to piece together the pre-history of storyboarding: the lack of surviving material, the sometimes unclear original usage of the documents that have survived, and the difficult task of defining what exactly might be considered an early or prototypical storyboard and what should not. Similar problems have confronted historians of early screenwriting, but there are significant, and revealing, differences.

Arguably, the need for screenplays came into being with the introduction of narrative films around 1903. Prior to this point, the unique attraction of film lay in its ability to represent the movement of objects that were not physically present in the space in which the spectator was situated. By the early years of the new century, however, relatively complex narratives were being devised by such film-makers as Edwin S. Porter in the United States and George Méliès in France; and while the surviving evidence is sketchy at best, it seems likely that what Edward Azlant terms ‘the prearrangement of scenes’, to facilitate the preparation and telling of a narrative tale in cinematic form, brought about ‘the birth of screenwriting’.1 More or less simultaneously, film-makers began to create written texts for an entirely different reason: to copyright their work in the face of the film piracy that was particularly rampant in the United States at this time. While the resulting texts look very different from the screenplays of today, the combination of these two commercial imperatives resulted in the creation of documents that can reasonably be held to have many of the functions of screenwriting practice today. Until the copyright amendment of 1912, however, there remained ‘a virtual free-for-all in the film business as making and distributing movies became increasingly profitable, with companies borrowing freely from each other’s films as well as from literary properties and seldom, if ever, giving proper credit’.2 After this date, a film-maker seeking to copyright a film with the Library of Congress would have to deposit evidence of its existence. Commonly, submitted material included ‘press books, scenarios, synopses, credit sheets, or photographs’.3 Sketches, however, would not serve the same function, and are generally absent. In short, while questions of copyright materially advanced the development of early American screenwriting, it did not have the same impact on storyboarding.4

The widely received understanding of what a storyboard looks like also poses potential problems when attempting to trace the form’s early history. In the context of archival work it requires that the researcher be alert to the cataloguing process itself. One example from the British Film Institute’s Halas and Batchelor archive saw nine colour illustrations, mounted, three per page, upon black A4-sized card simply defined as Animal Farm (1954) storyboard material. While the individual images are pre-production artefacts, from the archival description it was unclear whether the images had been produced in a formative storyboarding mode to plan a sequence of animation, or rather as a colour study to plan the visual mood of the sequence. The latter is accurate. As Vivian Halas and Paul Wells detail in Halas & Batchelor Cartoons: An Animated History (2006), first a comprehensive set of board-mounted, black and white pencil storyboards were produced to plot ‘the continuity of the film’, before Philip Stapp ‘joined Joy Batchelor in writing and producing a colour storyboard’.5 Troublingly, in Fionnuala Halligan’s more recent The Art of Movie Storyboards (2013), although two of the colour storyboard pages are reproduced, no reference is made to the formative, black and white pencil storyboard that would have informed these later colour boards.

As this example shows, the task of defining storyboard material in the broadest sense is problematic. Eadweard Muybridge’s serial photographs of animal and human motor function serve as a useful illustration. Arranged on the page as a series of independent yet related panels, both recording and suggesting motion through the movement of the reader’s eye, Muybridge’s photographic studies do indeed share a number of visual similarities with what might now be called a storyboard. However, Muybridge was not concerned with planning for motion, but rather capturing and revealing it. As Philip Brookman writes:

Muybridge created an analogous spatial grid of vertical and horizontal lines against which the time-based movements of his subjects were plotted. This grid of evenly spaced and numbered vertical lines, intersecting with the horizontal rules across the bottom of the frame, was designed specifically to mark the space so as to enable a scientific and visual interpretation of how his subjects moved through a defined fragment of space and time. Muybridge’s strategy of presenting photographic information against the backdrop of a numbered grid was helpful in a variety of ways. The photographer used it to order his myriad images, and to mirror the grid structure of individual pictures in his final presentation of an entire sequence.6

Although it is tempting to point to Muybridge’s latter endeavours to (re)animate his studies, thus bringing his panelled pages more closely in line with the remit of the conventional storyboard, this miscasts the work’s original intention.

Given the lack of a singular starting point in the development of the storyboard as a document and storyboarding as a process, this opening chapter covers what might be considered the form’s early or formative period, including the role that pre-production sketches played in the work of Georges Méliès; the early twentieth-century comic strips of Winsor McCay, and the question of whether these represent the first systematic and visible use of ‘storyboarding’ practices; and how live-action directors such as Cecil B. DeMille, D.W. Griffith, and Sergei Eisenstein made use of storyboarding processes in the 1910s and 1920s.

Georges Méliès

Méliès was perhaps the most prolific early adopter of pre-visualisation strategies. When planning his film projects, he produced numerous detailed drawings to help establish how characters would interact in scenes, and where they would be placed in relation to other points of action or interest. In fact, the large number of drawn pre-production materials produced by Méliès often causes him to be acknowledged as a ‘pioneer’ or ‘precursor’ in many of the practical ‘How to’ manuals, which promise to teach readers how to craft the perfect storyboard and carve out a successful career in the process.7 Méliès was not a storyboard artist, however, nor did he employ someone in such a role; rather, he recognised the value to the efficient planning of his fantastical films from sketched illustration. Consequently, the sketches created and utilised by Méliès directly resemble the rough, pre-production work that is still penned today by production designers when tasked with crafting a new costume or piece of set. His pre-visualisation work is therefore best considered here as something of a first step towards the more formalised storyboarding process that we recognise today.

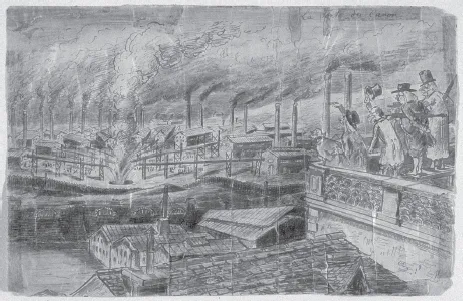

The sketches produced by Méliès around the time he worked on Le Voyage dans la Lune/A Trip to the Moon (1902), which are reproduced in Jacques Malthête and Laurent Mannoni’s L’Œuvre de Georges Méliès (2008), range in origin: some were produced at much later dates to serve as promotional illustrations in exhibition catalogues, while others may genuinely have contributed to the pre-production process.8 The sequence depicting the industrial-scale smelting plant, which is dated 1902, offers a particularly clear example of this latter application (Figure 1.1). It is striking to see how closely the finished film reproduces Méliès’ initial vision. Comparing the planning sketch titled ‘Le Fonte du Canon’ (which roughly translates as ‘the smelting of the gun/barrel’) with a corresponding frame from the recently restored colour edition of Le Voyage dans la Lune, it is clear that colour was being used to convey the ferocious mechanical ambition of the late Industrial Age.

Although hand colouration was not standard practice in the early cinema, Méliès made frequent use of the technique. In this instance, the sketch serves to establish the dominant colours that would be applied by hand to each frame: reds and oranges reflecting the heat of industry; blues and greys suggesting the cool and calculated of advance of science, alongside the increasingly wrought landscape of industrial France.9 The arrangement of the scene is also carefully planned in the sketch. In addition to calculating in advance the positioning of the astronomers and scientists, down to the waving of a top hat and the carrying of an umbrella, the sketch might also have served as a way of planning what proportion of the mise-en-scène could be filled with painted background and what would need to be physically constructed.

Figure 1.1 A colour sketch (reproduced here in black and white) created by Méliès for Le Voyage dans la Lune/A Trip to the Moon, c. 1902. Permission courtesy of Bibliothèque du Film, La Cinémathèque Française.

Similarity between Méliès’ pre-production sketch work and his staging of the pro-filmic event is evident in many of the director’s projects. In particular, Les Aventures de Robinson Crusoé/The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1902), La Légende de Rip Van Winkle/The Legend of Rip Van Winkle (1905), and Les Quat’Cents Farces du diable/The 400 Tricks of the Devil (1906) all reveal striking levels of visual continuity between pre-production sketches and their corresponding film scenes.10 Furthermore, those sketches that were produced by Méliès with promotion in mind, after the completed production of film, may yet serve as instrumental documents in the restoration of a long-lost strip of film. As Harvey Deneroff notes in relation to Le Voyage dans la Lune, ‘All known hand-colored prints of the film were considered lost until 1993, when a copy, in very poor shape, was turned up by Filmoteca de Catalunya in Barcelona’.11 Naturally, the team behind the restoration of the film, which was completed in 2010, turned not just to the surviving black and white film reels for reference, but also to Méliès’ sketch material, both pre- and post-production. This return to – and repurposing of – the Méliès sketches gives added weight to the assertion that Méliès ‘story-boarded moving images for the first time’,12 an argument proposed by Lobster Films’ Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange, the duo responsible for leading the film’s restoration.

Although it might be tempting – especially here – to consider Méliès’ pre-production sketches as constituting an origin story in the history of storyboarding, a reading of this nature distorts their original form and function. Such sketches, while related to the storyboard, are not quite storyboards. Prosaic as it may seem, a crucial ingredient of the classical storyboard form is the serial combination of multiple, discrete images within a larger containing frame, be that a sheet of paper, cork boards lining the walls of a film’s production office, or the screen of a computer or tablet.

Reframing the comic strip

Although there is a temptation to cast the net as broadly as possible when attempting to reclaim and establish an early history of storyboarding, it is essential to keep in mind the common conventions that inform our received understanding of the form. Despite such warranted circumspection, however, one storytelling medium, already well established by the end of the nineteenth century, looms large as a credible antecedent to the modern-day storyboard: the comic strip.

Comic strips, and comic strip anthologies, can be thought of as texts ‘in which all aspects of the narrative are represented by pictorial and linguistic images encapsulated in a sequence of juxtaposed panels and pages’.13 With this description in mind, the association with the storyboard becomes clear, especially when considering how the average storyboard also arranges information visually on the page, employing discrete panels to delimit each suggested shot. Furthermore, as Pascal Lefèvre notes, ‘There is a closer link between cinema and comics than between other visual arts. Films and comics are both media which tell stories by series of images: the spectator sees people act – while in a novel the actions must be verbally told. Showing is already narrating in cinema and comics’.14 It is hardly surprising, then, that static comic strip images, which reveal narrative when read, were quickly viewed as ready-made blueprints for moving image production.

Scott McCloud’s influential Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1994) contains ideas that, whilst not intended to address the subject of storyboarding, nonetheless c...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-history of Storyboarding

- 2 Storyboarding at Disney

- 3 William Cameron Menzies, Alice in Wonderland, and Gone with the Wind

- 4 Storyboarding, Spectacle and Sequence in Narrative Cinema

- 5 Hitchcock and Storyboarding

- 6 Constructing the Spielberg-Lucas-Coppola Cinema of Effects

- 7 Storyboarding in the Digital Age

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Index

Normes de citation pour Storyboarding

APA 6 Citation

Price, S., & Pallant, C. (2015). Storyboarding ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3484822/storyboarding-a-critical-history-pdf (Original work published 2015)

Chicago Citation

Price, Steven, and Chris Pallant. (2015) 2015. Storyboarding. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3484822/storyboarding-a-critical-history-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Price, S. and Pallant, C. (2015) Storyboarding. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3484822/storyboarding-a-critical-history-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Price, Steven, and Chris Pallant. Storyboarding. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.