eBook - ePub

Crisis in the Eurozone

Causes, Dilemmas and Solutions

M. Baimbridge,P. Whyman

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Crisis in the Eurozone

Causes, Dilemmas and Solutions

M. Baimbridge,P. Whyman

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This book explores the background of the eurozone crisis, outlining a number of potential solutions. It attempts to discover if the problems could have been anticipated, and examines how well have the fiscal EMU rules been adhered to and how appropriate they are.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Crisis in the Eurozone est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Crisis in the Eurozone par M. Baimbridge,P. Whyman en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Volkswirtschaftslehre et Ökonometrie. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sous-sujet

Ökonometrie1

The Eurozone as a Flawed Currency Area

Introduction

Advocates of membership in the eurozone argued that a European single currency could unleash economic potential that would increase economic growth and investment, achieve low and stable inflation and build a strong European economy through: encouraging greater trade; reducing transaction costs; and increasing price transparency. In terms of new institutions, the European Central Bank (ECB), through ensuring price stability, would result in lower inflation and interest rates, thereby again boosting investment and economic growth. Additionally, the euro would establish itself as a major world currency, conferring economic advantages and political prestige based upon the European Union’s combined economic strength. Finally, arguments that eurozone membership reduces national sovereignty were rejected on the grounds that, due to the globalisation of financial markets and to voluntary limitations imposed by international treaties, sovereignty is not absolute any more (Baimbridge et al., 2000).However, many critics have argued that the costs of entry into the eurozone were, in fact, potentially far greater where the loss of monetary and exchange-rate policies weakens national economic management, which is further constrained by the restraints upon fiscal policy. Further, the lack of prior cyclical and structural convergence created strains such that unsynchronised business cycles and/or structural differences magnify the effects of asymmetric external shocks. This is potentially further exacerbated by the absence of any substantial fiscal redistribution mechanism to offset less competitive areas suffering declining incomes and persistent unemployment. Additionally, a unified monetary policy would be unable to meet the needs of all economies through concentrating upon the ‘average’ member state. In terms of rules and institutions, the ‘generous’ interpretation of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) convergence criteria implied that the majority of participants must continue to deflate their economies in order to meet the rigid financial criteria established by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). Finally, the ECB is fundamentally undemocratic because it is deliberately insulated from all political influence (Baimbridge et al., 2000).

There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the combination of tight fiscal policy, mandated by the SGP and the conservatism of the ECB has already resulted in the eurozone economy suffering a decade or more of slow growth. Since the inception of the euro many commentators have argued that, despite its resilience against immediate collapse due to the volume of political, and from 2010 financial, capital invested in it by the EU establishment, the euro remains a fundamentally flawed creation (Minford, 2002; Baimbridge and Whyman, 2008). Therefore, the eurozone constitutes a ‘leap in the dark’ with potentially destructive implications if its participants are insufficiently convergent, cyclically and structurally (Eichengreen, 1990, 1992, 1993).The reasons are varied: The eurozone fails to fulfil, or even approach, the optimum convergence criteria agreed by economists to be the minimum requirement for the efficient operation of a monetary union; crucially, the Eurozone lacks an adjustment mechanism to meet inevitably changing economic circumstances, both internal and external, other than price and income deflation; its governing institutions, the ECB and the European Commission, are not subject to democratic accountability, let alone democratic control; the eurozone was adopted for essentially non-economic motives as the next stage of an integrationist European project, but without the necessary political coordination underpinning it.

In addition to these longstanding potential problems inherent with the creation of the eurozone, its design – in terms of risks emanating from spill-over and free-rider effects that result from a lack of fiscal discipline – has been relentlessly exposed following the 2008 credit-crunch-induced recession. Whilst fiscal policy should theoretically be used as a countercyclical tool, governments can also use fiscal policy for purely political reasons; however, if this is the case, fiscal policy may become challenging within a monetary union such as the eurozone through the occurrence of spill-over or free-rider effects (von Hagen and Wyplosz, 2008). The former effect may occur if eurozone members run large budget deficits over a prolonged period of time, which leads to their fiscal stance being on an unsustainable path and which, given its financing through the financial markets, results in ever-higher interest rates on sovereign debt. Additionally, with such a growing recourse to the financial market, the availability of financing may decrease and, therefore, drive interest rates up further. Thus, one member’s debt issue spills over to others as financing sovereign debt becomes more expensive for all countries (Arezki et al., 2011).The potential hazard of free-rider effects materialises when a country cannot meet the repayment of its outstanding debt and, with default on the horizon, undertakes either a surprise devaluation or inflation to reduce its debt’s real value. However, for eurozone members without sovereign monetary policy, these methods are no longer available, thereby increasing the possibility of outright default (McKinnon, 1996). Moreover, with the integration of financial markets, one country’s bonds may be widely held by other members. Thus, outright debt default harms not only domestic bond holders, but other government and private investors holding such bonds. Consequently, the pressure to bailout troubled fellow members may increase and, without restrictions on fiscal behaviour, a member country may allow its debt to increase continuously if its government believes that other governments will bail it out. Under a currency union, member countries lose not only their monetary independence but also a central bank to back their sovereign debts; thus, when it comes to possible default, eurozone governments become uniquely vulnerable to self-fulfilling panic. Additionally, the connection between the operation of the euro and the recent worldwide economic recession provides an illustration that national self-governance offers the potential for superior economic performance.

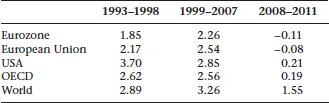

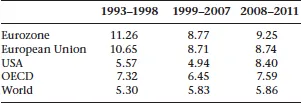

To review the economic performance across the economies of the EU with particular reference to recent events, Tables 1.1 and 1.2 present an overview of mean GDP growth and unemployment rates for several key time periods: from the completion of the Single Internal Market to the fixing of exchange rates for eurozone countries (1993–1998), to the operation of the eurozone prior to the ‘Great Recession’ (1999–2007) and to the recession itself (2008–2011). For comparative purposes the information is shown for a number of economic regions in addition to the eurozone itself. It is noticeable how relatively poorly the eurozone has performed, with the slowest GDP growth and the highest unemployment rate across all periods. Such stylised facts lend support to the hypotheses that the eurozone is far from optimal, through having failed to provide the ‘safety in numbers’ that can contribute to weathering shocks.

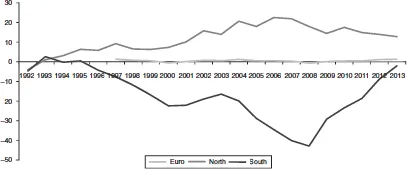

Further problematic symptoms that the financial crisis has highlighted within the eurozone are the balance of payments (BoP) difficulties that some members have experienced, together with the divergence of external balances between members (see Figure 1.1). In relation to the rest of the world (RoW), the countries in the North (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands and Austria) have persistently experienced current account surpluses, whilst those in the South/Periphery (e.g., Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) have experienced persistent current account deficits, despite an approximately balanced overall position (Holinski et al., 2012). Although originally perceived to be irrelevant, with the focus being on the global balance of the eurozone, these divergences are now partially identified as sources of the eurozone crisis (Sawyer, 2012). It is therefore pertinent to review the policy options for individual eurozone members to correct such BoP disequilibria and evaluate their desirability.

Table 1.1 Mean GDP growth rates (%)

Initially, following the advent of Keynesian demand management, policy prescriptions were advocated to resolve external imbalances and aid adjustment mechanisms (Crockett, 1982); however, several policies are unavailable to individual eurozone members. For example, notwithstanding their criticisms, the short-term, expenditure switching policies/elasticities approach that advocates changes in relative price levels between countries, through either appreciations/revaluations or depreciations/devaluations (Södersten and Reed, 1994; Pilbeam, 2006). However, despite the unavailability of such policies, Jaumotte and Sodsriwiboon (2010) argue that eurozone countries could mimic this approach in the short term through ‘internal devaluation’ to restore competitiveness by decreasing labour costs and, hence, relative price levels. Policy options include decreased social security payments, reducing indexation of wage increases, or through minimising minimum wage growth. For example, if Greece and Portugal moderated minimum wage increases to those experienced by northern eurozone members, this would improve current account balances by 2–2.5% points (Jaumotte and Sodsriwiboon, 2010). Indeed, such measures are essentially those imposed upon bailout economies that have proved politically and socially problematic; however, it should be noted that if all southern eurozone members adopted such policies there would be little gained in relative competitiveness (Duwicquet et al., 2012).

Furthermore, the use of direct controls (e.g., tariffs, quotas and embargoes) are also excluded policy options, whereby trade policies are negotiated on behalf of all EU members, thus individual nations are unable to apply direct controls against the RoW (Lea, 2010). Additionally, longer-term policy options that emphasise BoP imbalances as entirely monetary phenomena are also unfeasible (Williamson and Milner, 1991); since eurozone members cannot control their narrow money supply, together with the prohibition of capital controls, then they possess no control over credit creation (Arestis and Sawyer, 2012). Therefore, eurozone members must either control their growth rates to prevent inflation, or face losing international competitiveness (McCombie and Thirlwall, 1994). Consequently, only a limited number of policy options are available to individual eurozone members. In the short term, the traditional approach emphasises the use of changes in the level of domestic spending, or absorption (Pilbeam, 2006). For example, in current account surplus countries such as Germany the policy prescription would be expansionary fiscal policy to stimulate the economy and increase imports to resolve the imbalance (Jirankova and Hnat, 2012). However, such policies may conflict with internal balance; for example, Germany has typically operated at full employment output, such that any expansionary fiscal policy to increase absorption would create inflation (Arestis and Sawyer, 2012). Furthermore, since fiscal policy is limited due to the Stability and Growth Pact, the burden of adjustment is asymmetrically imposed on deficit countries (Ahearne et al., 2007). Similarly, in BoP deficit countries, contractionary fiscal policy is required; however, domestically these countries are experiencing low growth and high levels of unemployment (Chen et al., 2012); thus, such policies create a trade-off between internal and external balances, whereby there is a sacrifice of domestic goals (Thirlwall and Gibson, 1992). Hence, obtaining simultaneous internal and external equilibrium using only one policy is problematic; Tinbergen (1952) seminally proposed that the number of targets requires at least an equal number of instruments, whilst Mundell (1968) advocated that policies should be assigned based on their relative effectiveness. Arguably, fiscal policy has a greater effect on the domestic economy, whilst monetary policy (through interest rate differentials) attracts capital flows and is therefore more effectively assigned to the BoP (Pilbeam, 2006). However, for eurozone countries monetary policy is controlled at the ECB supranational level, such that national governments are (residually) left with fiscal policy to attain simultaneous equilibrium (Holinski et al., 2012); therefore, the adjustment mechanism is more difficult and uncertain (Duwicquet et al., 2012).

Table 1.2 Mean unemployment rate (%)

Figure 1.1 Current account balance (%of GDP) for eurozone members 1992–2013

Source: IMF (2012).

The eurozone’s fundamental structural weakness

These aforementioned weaknesses in the design of the eurozone are permanent, but they become more damaging in times of crisis. In the wake of the worldwide financial recession, the eurozone suffered a series of debt crises in individual member states. To date, the eurozone’s response has been piecemeal: ad hoc loans have been provided, whilst minor revisions to the Lisbon Treaty were agreed to enable the creation of a bail-out fund, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) to become the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) from 2013. Such ‘solutions’, however, deal with the symptoms rather than the fundamental causes of the euro’s structural weaknesses. This weakness ensures that recurrent problems will emerge that vitiate proposed remedies once they affect a large member country. Although the immediate origin of present discontents is usually located in the September 2008 collapse of the American investment bank, Lehman Brothers, its European antecedents lie in the bubble of speculative finance that occurred in the initial decade of the 21st century. This was intensified by the requirement to impose uniform interest rates in order to create an artificial monetary union amongst nations that did not always meet even their own restricted (financial not ‘real’) convergence criteria. Specifically, when the euro was introduced, the prevailing interest rate on 2 January 1999 stood at 3.25% for the three month Euribar (Euro Interbank Offered Rate), and, to achieve this target, nominal rates in France, Italy, Spain and Germany had fallen significantly in the previous nine years (O’Connor, 2009). Unsurprisingly, massive foreign investment ensued and stock markets boomed, whilst house prices and household debt levels soared. Inevitably, in such a low interest rate environment, investment banks and pension funds sought greater rates of return from alternative asset classes. Consequently ‘structured products’ developed, becoming the norm for investment in higher-yielding loan assets.

The strength of the euro until 2010 was determined by the German economy’s competitive power, which brought about deflation in several other eurozone members, since having the same interest rate for all countries created a ‘boom–bust’ cycle in a number of them. Hence, the growth rate across the zone languished, whilst unemployment as well as government budget and trade deficits multiplied. Additionally, in 2007 the German coalition increased value-added tax by 3%, which financed concessions to industry so that Germany could compete at a higher exchange rate, but in the process intensified the problems of its eurozone ‘partners’. Furthermore, the actions of the ECB – as the institution responsible for the one-size-fits-all monetary policy in the eurozone – also contributed to the series of events contributing to the crisis. Initially, in 2002–2003 the ECB adopted a low interest rate policy, which stimulated financial speculation. However, after 2005 the ECB changed its strategy so that rates climbed until the autumn 2008 crash. Indeed, it bowed to German pressure in June 2007 and as late as July 2008, raising interest rates to curb ‘external inflation’, despite an already-tight monetary environment. By definition, the ECB operates monetary policy for the eurozone as a whole, typically focusing upon the ‘average’ member state, so that the policy is often too tight for some nations, whilst too loose for others. Moreover, it is more difficult for the ECB to utilise monetary policy to regulate asset prices, whether stocks or housing, in individual nation states, where bubbles may occur. Thus, whilst few would claim ECB action to be the sole cause, it would be naïve to dismiss it as irrelevant rather than as a contributory influence. Although it might be argued that it is unfair to criticise the eurozone for struggling to deal with the negative consequences of the financial crisis, since it is by no means alone in this respect. Indeed, the Anglo-Saxon model was complicit in the loose regulation and speculative financial innovation that helped to precipitate the crisis in the first place. Nevertheless, although the ‘old’ European model could have avoided the worst of these failings through stronger financial-sector regulation and a more managed economy, it did not, and the current eurozone framework was at least a contributory factor.

Although this series of events exacerbated the inherent problems regarding the functioning of the eurozone, such difficulties could have been tempered if it had incorporated a coherent adjustment mechanism to meet inevitably changing economic circumstances. In a dynamic market economy characterised by technological and organisational progress, change is continuous: what Schumpeter (1942) famously termed the ‘gale of creative destruction’. Furthermore, since the Industrial Revolution all capitalist economies have experienced a cycle of periodic booms followed by periodic depressions. Consequently, it is crucial to the health of every economy that it possess a robust adjustment mechanism to enable it to accommodate efficiently to the inevitable transformations that will occur in its internal and external environment. However, the eurozone lacks this crucial element in its structure whilst simultaneously harbouring potentially damaging spill-over and free-rider problems. Thus, in the recent recession the eurozone’s members no longer possess independent monetary policies, so they cannot set interest rates or exchange rates to stabilise their economies. The current sovereign-debt problems faced by several participating nations demonstrate the simultaneous dangers of losing control of their borrowing costs and of the value of their currency to an external agency. Consequently, deflation – with all its economic, political and social costs – has become the eurozone’s sole adjustment mechanism, to the detriment of its citizens.

Conventional wisdom is that these contemporary crises are the product of deficient policymaking in the suffering countries, often expressed in moral terms as ‘indiscipline’ (Mills, 2011). In particular, budgetary policy has been too expansive and economies too competitively inflexible. The consequences of such errors are public expenditure cuts, increases in taxation and/or declining real wages. Additionally, conventional wisdom declares that once fiscal consolidation has occurred and labour market flexibility introduced, the countries concerned can return to non-inflationary growth, as Germany did after 2003. However, such conventional wisdom is misplaced, subjecting the eurozone to inefficient and ultimately unsustainable tensions. So long as the ECB tolerates weak demand in the eurozone as a whole and so long as the EU’s founder members (especially Germany) run trade surpluses, it will prove impossible for less-competitive nations to avoid insolvency. Their problems cannot be resolved by fiscal austerity alone, but only by a large rise in the external demand for their output. However, in a eurozone without monetary or exchange-rate offsets, any reduction in public expenditure generates at least an equivalent reduction in output. For example, an attempt to cut a fiscal deficit by 10% of GDP through reductions in spending would involve an actual reduction of 15% in GDP once declining tax revenues have been taken into account (Holland, 1995). A diminution in purchasing power of this magnitude would create a spiral of debt deflation in which the cost of meeting unpaid debts leads to low growth, falling prices, loss of jobs and declining living standards (Minsky, 2008). This ‘perfect storm’ increases the risk of default and, therefore, is likely to cause long-term interest rates to rise, the very thing that the adjustment policy was designed to avoid. Such a scenario carries dire consequences for future productive potential, leading to political dislocation and social distress (Baimbridge et al., 1994).

Almunia et al. (2010) compared the operation of the interwar gold standard with that of the euro, arguing that both systems are undermined as much by persistent surplus countries as by persistent deficit countries. Indeed, the more so because those in surplus are under no compulsion to change and are un...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Eurozone as a Flawed Currency Area

- Part I The Economics of Monetary Integration

- Part II Contemporary Economic Policymaking

- Part III Solutions to the Eurozone Crisis

- Bibliography

- Index

Normes de citation pour Crisis in the Eurozone

APA 6 Citation

Baimbridge, M., & Whyman, P. (2014). Crisis in the Eurozone ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3486336 (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

Baimbridge, M, and P Whyman. (2014) 2014. Crisis in the Eurozone. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.perlego.com/book/3486336.

Harvard Citation

Baimbridge, M. and Whyman, P. (2014) Crisis in the Eurozone. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3486336 (Accessed: 1 July 2024).

MLA 7 Citation

Baimbridge, M, and P Whyman. Crisis in the Eurozone. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Web. 1 July 2024.