eBook - ePub

Sir Arthur Lewis

A Biography

P. Mosley,B. Ingham

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Sir Arthur Lewis

A Biography

P. Mosley,B. Ingham

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Sir Arthur Lewis was the first development economist, the first Afro-Caribbean to hold a professorial chair at a British university and the first black man to win the Nobel prize for economics. However, he believed his contributions to the well-being of the poor through social and political activism were as important as his economics.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Sir Arthur Lewis est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Sir Arthur Lewis par P. Mosley,B. Ingham en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Economics et Econometrics. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

EconomicsSous-sujet

Econometrics1

The Caribbean in Turmoil: Prologue to a Biography

1.1 Lewis’s trajectory

Sir Arthur Lewis is known to many as the first black (Afro-Caribbean) person to hold a professorial chair in a UK university, and as a winner of the first Nobel Prize to be awarded in Development Economics. His achievement, in fact, was very broad, and he made important contributions not only to economics, but also to political science, history and education. He aimed not only to understand the world but also to change it (as he was later to put it, ‘half my interest was in policy questions’1) and his attempts, from the 1940s to the early 1960s, to achieve a better and fairer world through social and economic reform rank equally with, even if they were much less influential than, the writings that made him famous.

All Lewis’s great work in economic analysis was produced (as we relate in Chapter 4) during a brief period between 1952 and 1955, while Lewis was working at Manchester University. His inspirational work in policy advocacy began earlier, in the mid-1940s during his time at the Colonial Office, and ended later, in 1962, after his failed attempt to hold together the East Caribbean Federation. But after the pointed summit of his pioneering development economics research and the flatter hills of his work in economic and social reform, his output became, with one or two exceptions, mundane. During his fifties and sixties, a period of peak earnings and reputation, when he won the Nobel Prize and became world famous, the creative excitement drained out of his work.

Our aim in this biography is to focus on those periods during which Lewis was producing work that was astonishing and out of the ordinary – the type of work that persuaded us that development economics was a career worth pursuing. However, the period of Lewis’s exceptional research creativity between 1952 and 1955 turns out to have had a rather lengthy and fascinating gestation period, and without six chance events things might never have fallen into place to make it possible. First, there was the invitation to Lewis from the Colonial Office to do a number of consultancies on colonial development from 1941 onwards. Second, there was the moral and intellectual support that Lewis received from the Fabian Society and the Fabian Colonial Bureau. Third, there was the invitation from Friedrich von Hayek in 1943 to write a set of lectures for LSE students which evolved into Lewis’s lifelong commitment to a global economic history project. Fourth, there was Lewis’s own fascination with economic history and with classical models of economic growth, which provided the germ-cell of his 1954 essay, Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Fifth, there was the invitation from the United Nations in 1950 to generalize the lessons from his Colonial Office experiences to the rest of the developing world. And finally there was Lewis’s own decision in late 1952 to explore Asia and thereby complement his knowledge of the African and Caribbean colonies with data on a region of the developing world he knew much less well. Without these six elements it is doubtful whether those great insights that came to fruition between 1952 and 1955 would have emerged. Additionally, though most of the time Lewis worked alone rather than as one of a team, his achievements were very much part of a social process, the roots of which lay in 1940s London, as we relate in Chapter 2, and in his birthplace in the Caribbean.

1.2 Early life in the Caribbean, 1915–33

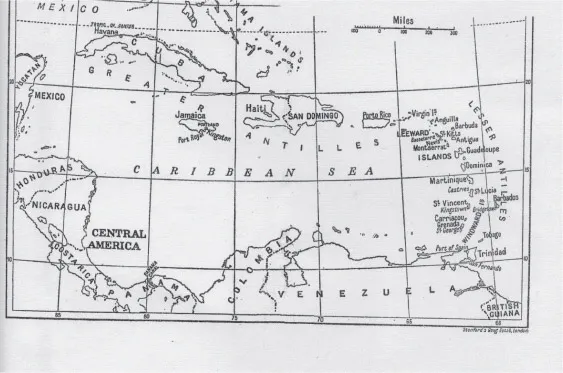

William Arthur Lewis was born on the island of St Lucia on 23 January 1915, the fourth of five sons of George and Ida Lewis, both of them school teachers, who had migrated from Antigua in the early years of the twentieth century. St Lucia is one of the smallest of the West Indian islands (see Map 1.1), which until emancipation in 1838 were based on sugar plantations worked by slaves. Even after the slaves had been freed, a huge inequality remained between the large landowners, nearly all of them white, and the workers and cultivators of smallholdings, mainly black. In the 1920s, when the young Arthur Lewis was growing up, this inequality pervaded the structure of power, and ambitious black people were subjected to an informal colour bar. As Lewis was later to put it:

This tiny white element dominates every element of West Indian life. Economically and politically the white man is supreme: he owns the biggest plantations, stores and banks. It is he whom the Governor most often nominates to his councils and for his sons that the best Government jobs are reserved.2

Map 1.1 The Caribbean in the 1930s

Source: W. M. Macmillan, Warning from the West Indies: A Tract for Africa and the Empire, Faber & Faber, 1936.

Within the black population there were gradations, some related to education and some related to skin colour, since the children of those black people who had interbred with white people enjoyed a status advantage. Lewis was later to describe how this operated:

Many West Indians react by trying to identify themselves with the ruling classes. They try to marry white, or to marry some fair person, and thus great importance is attached to lightness of complexion, the ‘high yaller’ despising the brown, and the brown despising the black. Such persons do their best to cut themselves off from all contact with the masses; become more reactionary than the whites; and in positions of authority often act with a harshness which makes many West Indians prefer a white master to a black.3

In the uneducated group, definitely the worst off were to be found among the half of the black population who worked in agriculture, most of whom (as well as a high proportion of those doing other jobs) experienced great deprivation, especially if they were casually employed. ‘Any teacher,’ to quote Lewis again,

can give cases of children coming into school on a breakfast of sugar and water, with no prospect of lunch. But far greater numbers eat enough and are yet malnourished because their diet is unbalanced … There is an abundance of starchy foods, but meat, milk and other fats are so expensive as to be beyond the reach of the working classes, except as Sunday luxuries. Consequently West Indians are prey to a number of diseases which weaken but do not kill, especially malaria, yaws, hookworm and venereal diseases.4

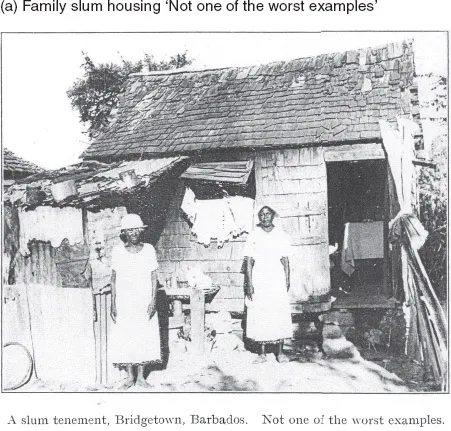

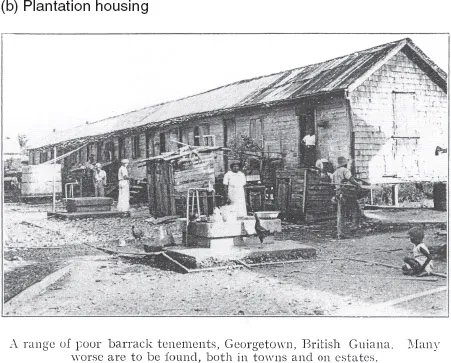

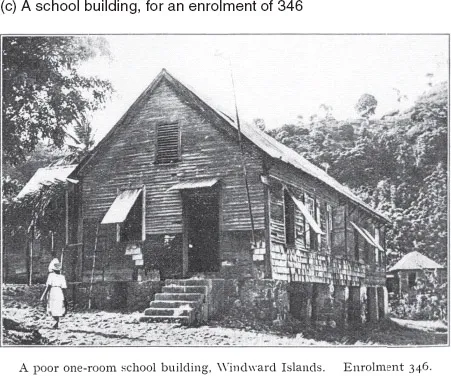

Vulnerability to disease was also caused by poor housing conditions, which on plantations consisted for the most part ‘of a long wooden building roofed with galvanized iron, divided from end to end by a partition, and subdivided on both sides into a series of single rooms – each of which would be occupied by a labourer and his family’5 (see Figure 1.1(b)).

Figure 1.1 Living and working conditions in the West Indies in the 1930s

Source: West Indies Royal Commission (see Moyne 1945); photos taken for and on behalf of Lord Moyne’s Commission to investigate social and economic conditions in the West Indies. Reproduced by kind permission of The Stationery Office.

The island of St Lucia is small and mountainous, with a population in 1914 of almost exactly 50,000, growing to 54,000 by 1930. The only sources of livelihood at that time were the white-owned sugar estates, smallholdings producing cocoa, citrus and bananas, and the civil service and professions. The years before the First World War had been prosperous for St Lucia’s trading economy, as the growing steamship trade had taken advantage of the safe harbour of Castries as an entrepôt port for coal, but the bottom fell out of this market in 1920 with the opening of the Panama Canal, and with the phasing out of coal as a fuel for steamships.6 The inter-war economy of St Lucia never recovered from these shocks.

Within the social structure of St Lucia, black professionals were placed immediately after the few hundred white planters and government officials, and within this group, George and Ida Lewis, as primary school teachers, enjoyed an exceptional status, putting them definitely within the top 5 per cent of income earners on the island at the time.7 There was only one secondary school, St Mary’s College in the capital, Castries. In Lewis’s day, primary and secondary education in St Lucia was dominated by the Roman Catholic French mission, the Fratres Mariae Immaculatae. The island’s prevailing language was an Anglo-French patois, which in the view of an English inspector of the time held back the island’s entire educational system.8 Derek Walcott, born 15 years after Lewis, in 1930, and the other St Lucian apart from Lewis to win a Nobel Prize, vividly represents the social stratification of the island, with, at the top, ‘bright row after row of orange stamps repeat[ing] the villas of promoted Civil Servants’, and at the bottom, the majority living in ‘two hundred shacks, on wooden stilts/one bushy path to the night-soil pits’ (Walcott, 1973, pp. 9, 37–39).

In this environment, the only way forward for ambitious young black people, including the Lewis family, was education, leading to a civil service job, and/or to get off the island.

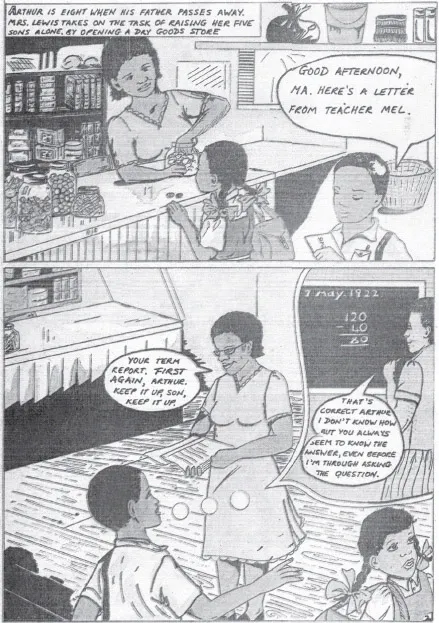

In January 1922, the young Arthur Lewis suffered an illness that forced him to miss school. His father, not wanting him to fall behind with his schoolwork, and realizing that the St Lucia primary school system was already holding him back, decided to tutor him at home, whereupon his progress, for a brief time, was extraordinary. As Lewis was later to relate: ‘He taught me in three months as much as the school taught in three years, so that on returning to school I was shifted from grade four to grade six. So the rest of my school life and early working life, up to the age of eighteen, was spent with fellow students or workers two or three years older than I’.9 (See the comic strip reproduced in Figure 1.2, published in the late 1980s by the St Lucia Schools Service in a programme to raise educational aspirations at the primary school level.)

Figure 1.2 Lewis’s early years as depicted in a 1987 comic strip

Source: Ellis and Bhajan (1987). Reproduced by kind permission of Lewis Archive, Mudd Library, Princeton University, NJ.

Not only did Lewis’s father educate him academically but also politically: he ‘took him to a meeting of the local Marcus Garvey association’ (formally the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League)10 ‘when I was seven years old’ (Breit and Spencer, 1987, p. 13). As Lewis was later to insist, ‘My interest in development was a product of my anti-imperialism’; and his anti-imperialism was born at an early age.

Only six months into this crash course, however, George Lewis died, in May 1922, when Arthur was only seven years old. Ida Lewis then single-handedly undertook the education of her five children, and to pay for it took on the lease of a grocer’s shop (depicted in Figure 1.2), hiring a manager to run the shop during the day while she continued to teach. In his later writings, Lewis took particular trouble, especially in his Report on the Industrialisation of the Gold Coast and in Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour, to highlight women’s role in development, well before the publication of Ester Boserup’s famous book of 1965, Woman’s Role in Economic Development, and indeed, in his autobiographical account, paying tribute to his mother, he wrote, ‘As a youngster in school I would hear other boys talking about the superiority of men over women; I used to think they must be crazy.’11

Apart from her extraordinary resilience, Ida Lewis had other exceptional gifts, notably musicality. Lalljie relates that ‘as she did with all his brothers, his mother made sure that he was also tutored in music. She herself played the harp, and would often play for all her sons.’12 A love of music, and specifically Western classical music, was thus inculcated in Lewis from an early age. He became an enthusiastic amateur pianist and concert-goer, and subsequently, any opportunity to express an opinion on music – from the programming of the BBC’s new Third Programme in 195213 to the curriculum of the Jamaica School of Music in 1961 – was eagerly grasped.

Lewis’s progress through primary and secondary school was rapid: he won a government scholarship to the Jesuit foundation of St Mary’s College at the age of ten, completed his Cambridge School Certificate at thirteen and his advanced certificate of secondary education (the equivalent of today’s A-level) at fourteen. Anecdotal evidence from this period records Lewis as being determined, unsociable and untrusting, keeping his thoughts and his possessions to himself, behaviour that was certainly encouraged by the fact that his schoolmates were older, bigger and stronger than he was.14 Among his fellow-students at school he became notorious for keeping his sweets to himself and not sharing them out.15 He was capable of great spontaneous generosity and gentleness towards others, but the evidence is that this side of his nature developed in later years. His graduate students with serious financial problems are known to have received advice and immediate practical assistance, in confidence, out of Lewis’s own pocket.

During all this time, the agricultural estates, the former mainstay of the economy, were crumbling, and all rural livelihoods were under pressure as a consequence of the global depression.16 The only hope was to capture one of the rare civil service jobs. At this point, at the bottom of the inter-war depression, the young Lewis had to mark time because he was too young to compete for a scholarship to study overseas, and so he took a minor job in the St Lucia Department of Agriculture.

So, outside work, Lewis prepared for what another West Indian boy brought up by a very poor but ambitious widowed mother was to call

this overseas examination, the most important event in our lives. It could determine whether we were going to b...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Caribbean in Turmoil: Prologue to a Biography

- 2 ‘Marvellous intellectual feasts’: The LSE Years, 1933–48

- 3 The Colonial Office and the Genesis of Development Economics

- 4 ‘It takes hard work to be accepted in the academic world’: Manchester University, 1948–57

- 5 The Manchester Years: Lewis as Social and Political Activist

- 6 Why Visiting Economists Fail: The Turning Point in Ghana, 1957–8

- 7 Disenchantment in the Caribbean, 1958–63

- 8 Princeton and Retirement, 1963–91

- 9 ‘The fundamental cure for poverty is not money but knowledge’: Lewis’s Legacy

- Notes

- References

- Index

Normes de citation pour Sir Arthur Lewis

APA 6 Citation

Mosley, P., & Ingham, B. (2013). Sir Arthur Lewis ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3488316/sir-arthur-lewis-a-biography-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Mosley, P, and B Ingham. (2013) 2013. Sir Arthur Lewis. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3488316/sir-arthur-lewis-a-biography-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Mosley, P. and Ingham, B. (2013) Sir Arthur Lewis. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3488316/sir-arthur-lewis-a-biography-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Mosley, P, and B Ingham. Sir Arthur Lewis. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.