eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling

Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun, Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling

Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun, Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The 2008 financial crisis was a watershed moment which clearly influenced the public's perception of the role of 'finance' in society. Since 2008, a plethora of books and newspaper articles have been produced accusing the academic community of being unable to produce valid models which can accommodate those extreme events.This unique Handbook brings together leading practitioners and academics in the areas of banking, mathematics, and law to present original research on the key issues affecting financial modelling since the 2008 financial crisis. As well as exploring themes of distributional assumptions and efficiency the Handbook also explores how financial modelling can possibly be re-interpreted in light of the 2008 crisis.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling par Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun, Emmanuel Haven, Philip Molyneux, John Wilson, Sergei Fedotov, Meryem Duygun en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Negocios y empresa et Finanzas. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Negocios y empresaSous-sujet

Finanzas1

Financial Development and Financial Crises: Lessons from the Early United States

Peter L. Rousseau

Introduction

The financial history of the United States is unique in that it includes multiple experiments with currency and banking systems that were accompanied by the rapid emergence of financial markets. This history is also reasonably well documented, and includes relatively frequent disruptions in the form of financial crises. More importantly, the U.S. experience from the colonial period through World War I holds lessons for understanding the interrelated roles of financial development, globalization, and financial crises in economic growth and stability, and these lessons are not entirely remote from the global events of 2007–2009. This chapter highlights some of these lessons through a financial historiography of the period that emphasizes the key role of central banks in economic stability, the dangers of allowing political expediency to drive economic outcomes, and the pitfalls of allowing either to gain excessive influence over financial and monetary policies.

The colonial period, the time surrounding the War of 1812, and the long period from 1836 until the founding of the Federal Reserve in 1914, all saw the United States without a federal bank. Although there were improvements from one episode the next, all three had more than their share of financial crises. In contrast, the two periods prior to the Fed when the United States did have a federal bank (1791–1811 and 1817–1836) saw greater financial stability, though more in the first period than the second. This chapter focuses on links between growth, volatility, the vulnerability to crises across pre-Fed U.S. history, and their implications for gaining a better understanding of the issues surrounding financial modeling in today’s post-crisis world.

1 The colonial period

The colonial period of pre-U.S. history commenced as British settlers migrated to North America in the early 17th century and ended with the fledgling nation’s Declaration of Independence from England on July 4, 1776. Most of the colonies engaged in some of the world’s earliest experiments with paper money. Although paper money had circulated at various times in China during and after the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.), the British North American colonies were the first to use it as a permanent financial instrument. The various colonial legislatures, starting with Massachusetts in 1690, printed this money, called “bills of credit,” with the consent of the colony’s Governor (i.e., the representative of the British crown) and then used the bills to purchase goods and services. These included payments to troops defending the colonies from threats by French, Spanish, and Native American forces, but some colonies also loaned the bills out to settlers to fund land purchases. The bills were officially backed by only the faith and credit of the issuing colony, but provisions accompanying their issue usually promised redemption at full value in lieu of taxes at pre-specified future dates.

When redeemed on schedule, the monetary theories of Sargent and Wallace (1981) and Sargent and Smith (1987) indicate that agents will increase their holdings of otherwise un-backed paper money in anticipation of a decrease in its supply on each redemption date. These promises of redemption (i.e., backing by anticipated taxes) maintain sufficient demand for the paper money so that new issues lead to a general level of prices that is smaller than the proportional increase specified by the quantity theory of money. The quantity theory states that prices should be in line with the money stock when velocity (V) and transactions (Y) are held constant in the “equation of exchange:” that is,

Indeed, issues of paper money in several of the colonies, such as New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania were successful insofar as prices did not advance in the same proportion as the circulation. Since colonial monies are generally believed to have traded at floating exchange rates with each other and with the British pound (McCusker 1978), these arrangements provided the individual colonies with some independent control of their monetary policies.1 But in cases where currency issues expanded excessively or the legislature failed to burn the bills as promised upon receipt as tax payments, doubts would arise among the public about the eventual redemption of outstanding bills at face value. When this occurred in New England after 1740 and in the Carolinas, the first financial crises in what would become the United States ensued.

South Carolina is a case in point, seeing large injections of currency in the 1710s, in 1730, and again from 1755–1760. In the first two instances the emissions were likely responses to threats, actual and perceived, from neighboring Spanish and Native American forces, while the final inflation coincided with the Seven Years War. Although the emissions may well have been put to good use in defending the colony, all came at the expense of a sharp decline in the value of the bills and severe losses to those left holding them during the fall. In New England, currency issues by Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island tended to pass at par for purchases across colonial boundaries, giving the region have the characteristics of an early currency union. Against this backdrop, the colony of Rhode Island, with one-sixth the population of Massachusetts, emitted quantities of currency that made its amount in per capita terms diverge rapidly, reaching more than five times that of its neighbors by 1840 (Rousseau 2006, 104). When New Hampshire increased its issues in response during the mid-1840s, the implicit taxes imposed by these two states on Connecticut and Massachusetts through depreciation of their own bills caused the system to unravel. By 1751, the British Parliament had passed the “Currency Act,” which forbade further issues of bills of credit in New England, in effect placing the region on a specie standard for the remainder of the colonial period.

The worst case of over-issuance of fiat currency, however, came shortly after the United States declared its independence from Britain. On the eve of the Revolutionary War, the national legislature, called the Continental Congress, agreed to issue bills of credit to finance the conflict. These bills, called “continentals,” were backed only by vague promises of specie redemption in the future, and presumably only if independence was achieved. Although the continentals allowed the nation to finance the early stages of the war, they began an unmitigated decline in 1879 to reach virtual worthlessness by 1781, and remained there until ultimately redeemed at a rate of 100 continentals to a single dollar when the new unit of account was introduced.

It is a little appreciated fact that the United States, buoyed by its new constitution, began its federal history with a default on obligations to its domestic note holders. Those in favor of the default argued that it was expected, that redemption at full value would primarily benefit speculators who had purchased the bills as option-like instruments that were deeply “out of the money,” and that as bearer instruments it would be impossible to identify those individuals who actually lost wealth as the continentals plummeted in the late 1770s. It turned out, however, that the default was essential to the nation restoring its credibility and creditworthiness in the international community.

2 The turnaround

Once it seemed clear that the nation would default on the continentals, questions of whether the federal government should have the right to charter corporations and whether individual states should be permitted to issue paper money came to the forefront late in the process of developing the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787. When the final document forbade individual states from issuing currencies and included a right for the federal government to “mint coins and regulate their value” through means “reasonable and proper,” however, it was not fully understood that this would imply a privatization of the money creation process. Of course, the outright ban on state currencies and the phrases quoted above created an impression that the federal government would be responsible for providing money, yet the coinciding ban on the federal chartering of corporations rendered the form through which the government would assume this responsibility unclear.

Indeed, Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury, removed any uncertainty by pressing forward after ratification of the Constitution by the states in 1789 with a proposal to charter a federal corporation – the (First) Bank of the United States. The entity would have an authorized capital of $10 million, with only 20 percent held by the government and the remainder by private investors. The Bank would act as fiscal agent of the federal government, holding its deposits and arranging for disbursements, and would issue its own specie-backed notes to circulate among the public. Some in the early Congress considered the federal charter of any corporation, including a “government” bank, as unconstitutional, and these sentiments persisted through the generation of the founding fathers and into the next. Nevertheless, Hamilton used the “necessary and proper” clause in the Constitution to justify the charter and then steered it through the Federalist Congress. The First BUS started operations in 1791.

Rousseau and Sylla (2005) describe the “Federalist financial revolution” as the set of innovations that brought the Bank into existence and followed on its heels. Hamilton had learned from the Bank of England (founded in 1694) and the Bank of Amsterdam (founded in 1609) how the ability to tender government debt in exchange for shares in a government bank could improve the state of a nation’s finances. And improvement was certainly needed given that the federal government and individual states were awash in debt from the War of Independence, with bonds selling at pennies on the dollar in the mid-1780s. Hamilton describes the plan in his 1790 Report on the Bank, in which he advocates for a privately managed, limited liability corporation divided into 25,000 transferable equity shares with a par value of $400 each. The Report calls for the federal government to purchase its 20 percent of the shares using a loan from the Bank to be repaid in installments over a 10-year period. Private investors would be offered up to 80 percent of the shares, with one fourth payable in specie and three-fourths payable in U.S. bonds paying six percent interest. The “6’s,” as they were called, represented a restructuring of the federal and various state debts. Even though this innovation had been used successfully a century earlier in England, it was still something of a surprise that the market value of the new U.S. 6’s sprung rapidly to par. By proceeding to make interest payments to foreign and domestic bondholders in hard money payable in the major cities, including London, Hamilton restored the credit standing of the United States and enhanced its ability to draw in capital from abroad. By defaulting on the continentals, Hamilton had made a difficult decision in favor of reliably servicing the restructured debt.

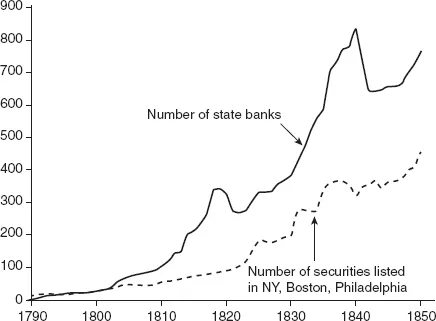

Figure 1.1 The number of state banks nationwide and security listings in three cities, 1790–1850

What happened next is nothing short of extraordinary. The number of private banks chartered by individual states rose rapidly to the point where the United States became the most banked nation in the world (Rousseau and Sylla 2005, 5–6). Starting with only three banks in 1790 – one each in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston – the nation attained 31 banks by 1800. Figure 1.1, which shows number of banks from 1790 to 1850, indicates that by 1811, when the 20-year charter of the First BUS was due for renewal, there were 117 banks, and that this expanded to 330 by 1825. Even in England, which had experienced its financial revolution a century earlier, the number of country banks in 1811 stood at only 230. By 1825, Sylla (1998, 93) shows that the United States had roughly $90 million in banking capital, which was 2.4 times the banking capital of England and Wales combined.

But this is moving ahead too far in the account. The innovation of the restructured 6’s and the transferability and popularity of shares in the Bank led to the emergence of markets for trading these instruments. Indeed, as Figure 1.1 also shows, the growth in the number of securities traded in the three major cities (New York, Boston, and Philadelphia) from 1790 to 1850 was extraordinary. Starting with a handful of government securities in 1790, by 1825 the United States saw 187 different securities trading in these cities compared to a total of 230 securities trading in the English markets (Rousseau and Sylla 2005, 6–9). The conclusion is inescapable: by 1825 the United States had a financial system that was gaining on the world’s leaders in terms of both banking and the spread of securities markets.

Sylla et al. (2009) show how the First BUS acted decisively to rout an incipient financial crisis in 1792 when speculation in government securities and shares of the First BUS in New York led to a substantial crash and scramble for liquidity among early stock brokers. The First BUS, under the direction of Hamilton, provided the necessary liquidity at this critical moment, thereby arresting the panic. Although the crisis itself is sometimes viewed as a minor event involving only a small number of wealthy individuals, the fact remains that the BUS engaged in the type of liquidity provision that would nowadays be associated with the operations of a central bank. This suggests that the United States had at least a quasi-central bank very early in its history.

With the spread of banking came true privatization of the money creation process. The First Bank’s federal charter granted it the right to issue specie-backed notes, and individual states granting bank charters also allowed this. There were no required reserve levels at the time, so these private banks could expand their issues to meet the needs of entrepreneurship, and also to maximize the profits of their owners. Since loans were often granted to bank “insiders,” the probabilities of large losses tended to be small, but resources were not generally allocated through a competitive process where funds went to projects with the highest potential returns. When banks did over-issue currencies, there was always the possibility that the public might choose to redeem their notes en masse and take the individual bank down.

Interestingly, bank failures were not a concern during the time of the First BUS. One reason for this was that the First BUS began to establish branches to facilitate the collection and disbursement of the government’s funds in the course of normal business. The first branches were established in Boston, New York, Baltimore, and Charleston (1792), and then later in Norfolk (1800), Washington and Savannah (1802), and New Orleans (1805) (Wettereau 1937, 278). Even President Jefferson, an original opponent of the Bank on constitutional grounds, came to appreciate the service that the Bank could provide as fiscal agent. More important for the stability of the system, however, the Bank and its branches also provided a check on paper money issues by individual state-chartered banks by collecting their notes through their ordinary operations and then deciding whether to pay them out at their own counters or to pack the notes up and return them to the counters of the issuing banks for redemption in coins. The decision was typically based on whether the First BUS could determine whether an individual bank was issuing more notes than it could redeem, and the amount of notes coming across its own counters provided a reasonable predictor. The possibility of sudden redemption by the BUS served to deter state banks from issuing too many notes. The Bank was so successful in conducting the operations that its shareholders, which included both the government and private individuals including foreigners, were paid healthy annual dividends of 7–8 percent on their stock in addition to the interest on the bonds that they had tendered for the shares.

The Bank’s fortunes changed rapidly in 1811, however, when opponents in Congress stopped the financial revolution in its tracks. At that time, the Republicans, fueled by Jefferson’s legacy and led by President Madison, who was even more ambivalent toward the Bank than his predecessor, caused a deadlock in the Senate on a bill to renew its charter for another twenty years just before it was to expire. The robust annual dividends were viewed by some of the Bank’s opponents as evidence that a wealthy elite was unduly benefiting from use of the government’s temporary balances for profit. Other opponents claimed that the Bank’s federal charter as a corporation was unconstitutional in the first place. In the end, sitting Vice President George Clinton (a former Governor of New York), in his role of presiding over the Senate, cast the deciding vote against the Bank, and it ceased operations as a federal bank in 1811.

3 1812–1828

The end of the Bank could not in retrospect have come at a worse time. As British troops threatened the new republic along its Atlantic seaboard and on the Gulf coast during the War of 1812 – hostilities that included the capture and burning of Washington DC in 1814 – the federal government desperately needed funding to prosecute the campaign. Without a quasi-central bank to organize the funding efforts, the government resorted to issuing $60 million in debt directly to the public, both within the United States and abroad. It also issued $15 million in treasury notes to make up the remaining shortfall. By 1814 it had become impossible to repay these debts on schedule due to their sheer volume, and this sounded a death knell for raising the additional debt required to service existing loans.

Indeed, the United States was bankrupt in late 1814, and many banks formed in the wake of the First Bank’s demise were having difficulty redeeming their own notes. It is amazing that in a time of such financial disarray General Andrew Jackson and his troops turned back the British in New Orleans in January of 1815 in the war’s most decisive victory! Yet never in the history of the United States had the need for a federal bank become more apparent. Realizing the error th...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Financial Development and Financial Crises: Lessons from the Early United States

- 2 Monetary Transmission and Regulatory Impacts: Empirical Evidence from the Post-Crisis Banking Literature

- 3 Market Discipline, Public Disclosure and Financial Stability

- 4 Strategic Monetary and Fiscal Policy Interaction in a Liquidity Trap

- 5 Analyzing Bank Efficiency: Are “Too-Big-to-Fail” Banks Efficient?

- 6 Efficiency, Competition and the Shadow Price of Capital

- 7 Model-Free Methods in Valuation and Hedging of Derivative Securities

- 8 The Private Information Price of Risk

- 9 Evolutionary Behavioral Finance

- 10 Post-Crisis Macrofinancial Modeling: Continuous Time Approaches

- 11 Recent Results on Operator Techniques in the Description of Macroscopic Systems

- Index

Normes de citation pour The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2016). The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3488576/the-handbook-of-post-crisis-financial-modelling-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2016) 2016. The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3488576/the-handbook-of-post-crisis-financial-modelling-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2016) The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3488576/the-handbook-of-post-crisis-financial-modelling-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Handbook of Post Crisis Financial Modelling. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.