![]()

1

Introduction: Securitization as Villain and Savior

Before 2007, I wager that very few academics, policy makers or indeed few outside a small coterie of specialists had any idea how important securitization was to the growth in the financial economy during this millennium.1 By now, however, it has been well established that the practice of transferring some or all of the risks of some financial products from the originator (a mortgage lender, for example) to end investors played a significant destabilizing role during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), and may have even been a primary cause of the worst economic turmoil since the Great Depression.2

As has been well, though not always accurately, documented in the press and – more recently – the academic literature, legislative and industry reaction to the GFC has generated many new regulations, regulatory agencies and governmental powers. There can be no doubt that some progress has been made in making the financial system more robust in the face of any GFC-like recurrence. For example, liquidity lines to the most highly levered vehicles during the GFC are now much more capital intensive and, therefore, discourage such leverage. Chapter 3 covers the broader changes, the elements of the new regime that indirectly affect the markets for securitization, as well as those specifically dealing with securitization. More changes to this larger regulatory regime for financial markets are still to come. On the other hand, there are still significant controversies to be addressed, with a notable example being the debate between the effectiveness of ‘simple’ versus ‘complex’ regulatory regimes and rules.3

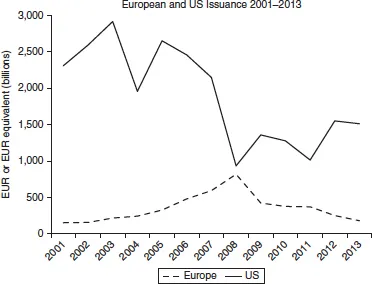

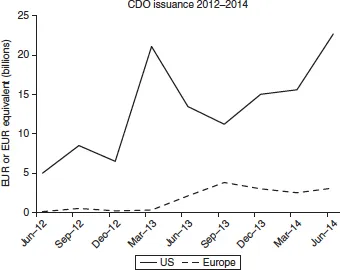

Though there have been wholesale changes to much of the financial regulation landscape in many countries, securitization regulation has remained, in the eyes of investors, banks, bureaucrats and politicians, one of the remaining unsolved puzzles of the post-GFC financial landscape.4 While securitization (and its regulation) continues to shoulder some blame for its role in the GFC, many securitization markets have returned as strong as ever (CDOs in the US, for example, as per Figure 1.2).5 Some regulators, especially those charged with designing the technical aspects of the regimes, and politicians in the most important financial centers, are not only cautious about encouraging but often downright refuse to allow bank activity similar to that which has been accused of causing some or all of the financial distress that has lasted from 2008 to the present. There are many who cannot be dismissed as cranks or luddites who claim that too much of the ‘wrong kind’ of lending is being done6 and that securitization has the potential to exacerbate this. Many of these commentators appeal directly to the public. On the other hand, a strange coalition of bankers, bureaucrats and politicians is calling for a softening of the current regulatory regime for securitized products on the basis that a lack of fully functioning bank lending markets is being blamed for the slow growth in both Europe (especially) and North America. Nothing gets legislative attention like trumpeting risks to real economic growth, especially in Europe. Lobbyists understand this, and keep pushing this notion that more securitization would benefit the real economy, without mentioning any possible risks.

Figure 1.1 Total securitization volumes 2004–2014: US and Europe

Figure 1.2 CDO issuance 2013–2014: US and Europe

Meanwhile, securitization has been little used by banks for risk and/or capital management purposes since 2008. Granted, securitization volumes appear to be mounting quite a comeback, but in Europe much of the new issuance goes straight to the European Central Bank in order to access low-cost funding. That is, the risk of the assets remains with the banks. If anything, there has been a shrinking of the market precisely because banks are often incentivized to repurchase their old securitizations. Such tenders and calls of legacy transactions may actually increase risks to the regulated system.

When regulating securitization we should determine to what extent we can have a ‘vibrant’ securitization market without returning underlying asset or financial markets to the excesses of pre-2007. While some securitization may not be harmful, it is likely that any ‘appropriate’ regime for its regulation will not resemble the pre-crisis structure, for reasons I discuss in Chapter 4. Securitization experts Viral Acharya and Matthew Richardson sum up the issue:

There is tremendous pressure on many sides to reopen the securitization markets as fast as possible, without the final formal rules having been put in place. According to two key central bank bodies, a restart to securitization is crucial to the continued recovery post-GFC as:

The ECB/BoE joint paper bemoans the lack of investor enthusiasm thusly:

Are they implying then that it would be better if investors threw caution to the wind as they did with subprime RMBS and CDOs in 2005 through 2007 (again, so soon?)?

Just as investors should be cautious when diving into opaque markets without the appropriate understanding of the risks, we as taxpayers as well as stakeholders in the global economy should not blindly in accept whatever the regulators and politicians decide, often in closed conversations with regulatees through industry lobby groups, is the ‘best’ system for regulating anything, let alone what has proven to be a fragile financial system. This is because, first, the use of rhetoric and discourse as well as highly technical arguments can be used to close off what are known as policy and regulatory ‘conversations’. For example, it is not at all evident that more securitization would stimulate bank lending, and therefore it’s not obvious that there is an explicit trade-off between allowing leverage in the system and economic growth. Yet this discourse is shared in many stakeholder communities.

The International Monetary Fund in its 2009 Global Financial Stability Report might have been the first to call, prematurely perhaps, for the restarting of securitization markets in spite of the possible negative effects of the past, due to its presumed positive effects on economic growth.10 Since then, many other international organizations (a group of the largest securities regulators, IOSCO,11 for example), politicians (in Italy, for example), industry groups (AMFE, for example) and regulators (the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, to name two) have united in their call for a reopening of the securitization market for bank assets such as business loans and mortgages that has been greatly reduced since the GFC.

In addition to the problem with hidden and possibly dubious assumptions, it is not at all clear from listening to the interested parties what the goals of regulation are and if whatever goals are proffered can be achieved through the relaxing or adjustment of the current regime. This problem is further compounded by the fact that securitization has two distinct but not mutually exclusive goals: it can be used for funding and/or risk transfer. Additionally, risks to the financial system depend on who is investing and in what products.

We’ve recently seen a meeting of the minds between the industry lobby and many senior politicians and bureaucrats that suggests that the current and proposed regulations governing securitization are ‘too onerous’, and that allowing lighter-touch regulation and capital requirements will allow the banking sector to lend again to the real economy, thus stimulating growth. Based on a panel at the dominant securitization industry conference in 2014, one panelist claimed that, while a Bank of England representative suggested that securitization was a ‘financing vehicle for all seasons’, ‘one thing I can say with certainty, securitization is not going to be the financing vehicle for any season if we continue down the current track’.12 That groups that have been at odds with each other for much of the crisis should come together is not only slightly ironic, but also potentially worrying. However, it is probably fair to say that securitization as a risk transfer or funding mechanism is not in itself good or evil.

The second reason to be wary of the new regulations is that there is an entire theory of regulation that posits that regulatees – that is, the financial industry – tend to influence regulations and their enforcement in their favor, especially when public and legislative attention wanes. One way to interpret the iterations away from safety in the Basel III capital requirements for European insurers is that lobby groups are demanding – and receiving – concessions through private negotiation. It behooves us as interested parties to take control of these regulatory decisions to ensure they are made in the ‘public interest’, however defined. Certainly there is significant evidence of such regulatory capture in the UK, Euro zone and US regulatory regimes, and this will be discussed in detail in Chapter 4. As such, this issue should never be taken lightly.

When designing regulation and policy as well as addressing issues to do with supervision and enforcement, it becomes important to understand the details of securitization, and in Chapter 2 I introduce and explain the nuances of the technology of repackaging assets and selling them in tranches of risk. In Chapter 3 I describe the GFC in terms of this securitization framework. Securitization was certainly a tool for adding leverage, but I will argue that it was not much more than that, and the GFC would have occurred without subprime securitization. Chapter 3 ends with a summary description of the current regulatory regime. In Chapter 4 I introduce and explain the scholarly literature on regulation in general and financial regulation in particular. There I also begin to relate the practical aspects of securitization with this knowledge base. In Chapter 5 the regulation literature and a full understanding of the nuances of securitization are combined to produce some important principles for regulating these markets. I end with some key recommendations and a few important considerations in Chapter 6.

1.1 Industry as organized lobby

Recognizing the importance of addressing the latest push to reform financial markets, the industry produces well-funded public relations campaigns, bolstered by intense behind-the-scenes lobbying. The theory predicts that this usually results in rules being softened over time. The public has in the past, and currently, been subject to constant pro-securitization propaganda from lobbyists, politicians and other interested parties. The most popular attack on regulation is labeling it disparagingly as ‘red tape’ and stressing its expense to industry and, consequently, a risk to jobs.

One of the most polarized and indeed polarizing commentators, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, was reported as documenting the supposed demise of the securitization of credit cards:

That is, his view is that regulation red tape causes the technology to be expensive, so bankers reject it. This is thought to be somehow bad for the economy. But in fact, banks have shown that they can lobby to avoid tighter regulation, as long as ‘you’ve got the right lobbyist and the right representative connected to Washington or the right ties to Washington’.14

Most stakeholders in the securitization markets with any power to influence policy already agree that ‘subprime was different’ from other, ‘better’, securitizations,15 and that securitization is useful.16 As such, there are in fact few credible or connected individuals or lobby groups who propose to aggressively control securitization.

1.2 The false dichotomy of ‘reform or repression’

The solutions that industry provides for more securitization unsurprisingly involve less regulation and looser capital requirements for holding securitized investments. There is often explicit assumption that more lending is needed in order for the economy to grow and that securitization is needed to fund the requisite lending.17 When paired with the argument that red tape and overly harsh capital requirem...