![]()

Part I

FOUNDATIONS OF EMPIRE

![]()

Chapter 1

Enterprise and Expansion, 1848–1885

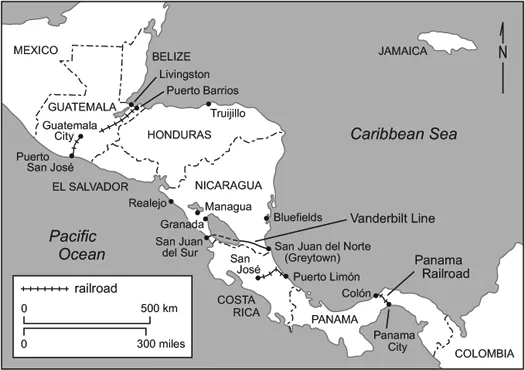

In February 1855, the Panama Railroad Company announced the official opening of the world’s first transcontinental railway. Located within what would become the Panama Canal Zone a half century later, the line connected Aspinwall (present-day Colón) on the Caribbean to Panama City on the Pacific. At the time, it represented the largest American investment outside the borders of the United States. In the weeks following its opening, stockholders of the New York–based company, including William Aspinwall himself, gathered in Panama, then a province of New Granada (Colombia), to celebrate. They drank toasts to the late John L. Stephens, a diplomat, writer, and prominent promoter of the project; they predicted a new age of commerce and progress. Above all, they cheered the railroad’s role in linking the United States to its new territories on the Pacific Coast. Yet they said little about the Colombian and immigrant laborers who had built the railway. Like the “natives” of Panama, the workers were silenced in the firm’s imperial narrative.1 The company itself suffered a similar fate in the United States. Although newspapers across the country celebrated the railroad, news of its completion soon gave way to other headlines. These featured not only the controversy over slavery in the Western territories but also the recent exploits of U.S. filibusters in Central America. Just four months after the Panama Railroad’s completion, a band of adventurers led by William Walker seized control of Nicaragua. When Walker reinstituted slavery in the conquered nation the following year, he thrust Central America into the domestic debate over slavery and territorial expansion.

Both filibustering and the Panama Railroad had their immediate roots in the U.S.-Mexican War. The 1848 victory over Mexico left thousands of young American men enthralled with conquest and convinced of their racial supremacy. It also yielded Pacific territories that lacked transportation links to the rest of the nation, a deficiency that became apparent when the discovery of gold in California brought a stampede of American prospectors. Although most made their way across the plains and deserts of the West, thousands more traveled via Nicaragua and Panama. That migration in turn drew the attention of U.S. adventurers, entrepreneurs, and policy makers to Central America. Whether they welcomed it or not, the region’s residents were about to be drawn into the process of U.S. expansion.

After 1848, that expansion would be shaped, to an extraordinary degree, by private interests. The most spectacular examples were the filibusters, whose campaigns to seize new territories by force received some encouragement from Washington. But the impulse for landed expansion slowed with the coming of the Civil War. Emancipation ended all talk of new slave states, and in the following years the U.S. government focused on domestic issues such as Reconstruction and railroad building. The completion of the transcontinental railroad to San Francisco in 1869 rendered the U.S.-owned railway across Panama virtually obsolete. But the same debates over race and citizenship that stalled further territorial acquisitions made the Panama Railroad Company a useful model for U.S. expansion. Indeed, although Washington’s attempts at formal overseas empire in the 1870s and 1880s proved halting, private American interests continued to entrench themselves throughout Central America and the rest of the Hispanic Caribbean. In the process, other U.S. enterprises experimented with their own versions of the business model and labor system first established by the Panama Railroad.

This connection was especially evident in Costa Rica and Guatemala. By the 1850s and 1860s, the coffee exports of both countries were growing quickly, due in part to new markets in California. In addition to reshaping regional land use and labor systems, this rising coffee sector brought to power ambitious “liberal” leaders who were determined to promote economic development at any cost. In both Costa Rica and Guatemala, their visions of progress hinged upon the construction of Caribbean railroads that could carry coffee to Atlantic markets. To build these lines, they turned to U.S. contractors, the most successful of whom was Minor Keith. Throughout the 1870s, Keith experimented with a number of labor sources in his quest to complete Costa Rica’s railroad. By the early 1880s, however, he had come to rely primarily on British West Indians. And just as the Panama Railroad prefigured aspects of the Canal Zone, Keith’s efforts in Costa Rica established the strategies of racial domination and labor control that would later characterize United Fruit’s enclaves.

Competing Empires and Contested Sovereignty

The Caribbean coast of Central America had become a contact zone between the Hispanic and British Caribbean long before U.S. business interests appeared. Since the seventeenth century, English merchants had dominated trade along the coast by establishing ties to local black and indigenous communities. The most important of these were the Miskito Indians, who lived under a British protectorate that stretched across much of the Honduran and Nicaraguan coasts. In the 1830s, however, such arrangements began to clash with the efforts of the new Central American states to establish their territorial sovereignty. In addition to the Miskito protectorate, British settlers and black Creoles controlled Nicaragua’s Caribbean port of San Juan del Norte, without which Nicaraguan officials could neither collect customs duties nor regulate commerce. Farther to the north, Great Britain ruled Belize, a predominantly black mahogany colony that Guatemala claimed was part of its national territory. From the beginning, then, the Central American states associated dark-skinned populations on the Caribbean coast with foreign threats to their sovereignty.2

A revealing glimpse of this British influence appeared in John L. Stephens’s famous account Incidents of Travel in Central America (1841). Arriving in 1839 to take up his post as U.S. minister to the collapsing Central American Federation, Stephens was struck by the West Indian character of the Caribbean coast. In Belize, he observed, “I might have fancied myself in the capital of a negro republic.” Along with the black majority came relaxed views toward interracial sex: in this British colony, he learned, “the great work of practical amalgamation, the subject of so much angry controversy at home, had been going on quietly for generations,…[and] some of the most respectable inhabitants had black wives and mongrel children whom they educated with as much care…as if their skins were perfectly white.” Equally shocking was the sight of black men in positions of authority. At the Grand Court, for example, he found that one of the judges was “a mulatto” and one of the jurors a “Sambo”—of mixed indigenous and African descent. Stephens admitted that he “hardly knew whether to be shocked or amused at this condition of society.”3

The U.S.-Mexican War transformed this British presence from curiosity to threat in the eyes of Americans. Following Washington’s seizure of California, many Americans came to view Central America, and particularly a future Nicaraguan canal, as integral to their new empire. It was in this context that the British navy formally seized San Juan in early 1848, renaming it “Greytown” in honor of Jamaica’s governor and attaching it to the Miskito protectorate. Americans bitterly denounced the move, with some U.S. newspapers accusing Great Britain of holding territory in the name of “drunken savages.” For its part, the Nicaraguan government promoted its own version of the Monroe Doctrine, declaring that “the extension and propagation of monarchical institutions whether by conquest, colonization, or the sovereignty of wandering tribes…on the American Continent, is contrary to the interests of the Republican States of America, and menaces their peace and independence.”4 By aligning itself with Washington, Nicaragua hoped to play the two powers against each other and reassert control over Greytown.

In April 1850, U.S. and British diplomats ended the impasse by signing the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which provided for mutual control and non-fortification of any Central American canal. In addition to preventing an imperial clash, the agreement likely facilitated the recruitment of British West Indian laborers for the recently begun construction of the Panama Railroad. Nevertheless, the treaty brought howls of protest from U.S. expansionists, in part because it failed to annul Miskito sovereignty. One American in Nicaragua complained that the United States was “playing ‘second fiddle’ to John Bull” by allowing London to retain Greytown in the name of a few hundred “shoeless naked Indians.”5 Such comments were hardly surprising. Americans had long accused Britain of sponsoring Indian resistance to U.S. expansion in the West; it now seemed to be doing the same in Nicaragua. But Secretary of State John Clayton expressed hope that Great Britain would soon “extinguish the Indian title…within what we consider to be the limits of Nicaragua,” adding that “we have never acknowledged, and never can acknowledge the existence of any claim of sovereignty by the Mosquito King or any other Indian in America.”6 In doing so, Clayton implicitly recognized Nicaragua as a “civilized” nation entitled to sovereignty. Soon, however, U.S. expansionists would challenge that status of the Central American states.

Map 2. Central American Transit Routes prior to 1904. By Ole J. Heggen

Isthmian Crossings

As U.S. and British diplomats sparred, California-bound prospectors brought changes to Central America. In Nicaragua, hotels, restaurants, and whole towns sprang up along the route from Greytown to Realejo, and prices soared as demand outstripped goods and services. The migration also began the process of reorienting Central American commerce toward the United States. Previously, regional trade had been limited to intermittent visits by British vessels. With the gold rush, however, U.S. merchant ships began arriving on the Pacific and Caribbean coasts, and the population boom in California provided a new market for regional exports, particularly coffee.7 The gold rush also had a significant social impact on Central America. American migrants carried with them domestic prejudices that often contributed to the abuse of local residents. This sometimes took an anti-Catholic bent. In June 1849, for example, a U.S. traveler refused to doff his hat during a religious procession in Chinandega, Nicaragua, and drew a pistol on a priest who tried to remove it for him. Other Americans viewed Central America as an outlet for their sexual desires, forcing themselves on local women or marrying under false pretenses. In 1853, for example, former U.S. diplomat E. George Squier reported that in Granada, a man named Walcott had “married a very respectable girl of the country, & afterward left her, having a wife or two in the States.”8 Such incidents inevitably stirred anti-American resentment.

Americans in Central America, like U.S. visitors to the British Caribbean, were often flummoxed by the racial complexity of local society. When informed by a Nicaraguan that local rebels “want to kill all the white inhabitants” of the nation, for example, gold prospector William Denniston mocked Hispanic pretensions to whiteness, asking how it would be possible “to draw the line of distinction between white and black in this country.”9 Other travelers fell back upon domestic class and racial assumptions. In June 1850, while traveling through Nicaragua, Michigan native Albert Chapman Wells observed that “the Negro Indian portion of the people resemble in character and disposition the Five Pointers”—referring to the predominantly black and Irish residents of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In Managua, his group convinced their landlord to “call on the Senoritas for our benefit during the evening,” but Wells claimed to recoil from “the half dressed—half brown half black and half white sooty faced damsels.” One girl agreed to dance with one of the Americans “upon condition that he paid her $2.” After much consideration, the man (who may have been Wells himself) declared he “would not pay a ‘nigger’ $2 to dance with him.”10 Sometimes the racial certainties of home could cushion a bruised ego.

These tensions only grew as U.S. capitalists consolidated their control over travel across Nicaragua. In January 1851, Cornelius Vanderbilt opened a transit line that utilized steamships, riverboats, and carriages to convey passengers from New York to San Francisco via Nicaragua. In its first four years of operation, the enterprise carried as many as 2,000 people per month. Although most Americans crossed quickly, a significant number remained in Nicaragua. Inspired by visions of Manifest Destiny, many predicted U.S. settlers would supplant native Nicaraguans or at least establish familiar color lines in place of the racial disorder they perceived. In October 1851, Wells, now living in Granada, asserted that American residents “look forward to the time when black blood will be forced to take the position that nature designed it should occupy.”11

U.S. influence was especially noticeable in Greytown, where British interests were giving way to both the transit company and a growing number of American settlers. Visiting in 1853, Squier declared it “in all respects & wholly a fine American town” destined to be controlled by the United States.12 But this U.S. influence brought tragic results. In May 1854, local residents attacked Vanderbilt’s property after one of the company’s American captains shot a black boatman. Determined to protect a U.S. firm in a strategically vital region, President Franklin Pierce dispatched the U.S. warship Cyane, which bombarded and virtually destroyed Greytown. To justify the destruction, Pierce cited the offenses committed by “a heterogeneous assemblage gathered from various countries, and composed for the most part of blacks and persons of mixed blood” with “mischievous and dangerous propensities.”13 It was not the last time a racialized threat to U.S. capital would spur Washington to imperial violence.

The impact of the gold rush was even more profound in Panama. Between 1848 and 1860, more than 200,000 Americans crossed the narrow Colombian province. Although racial inequality and conflict were hardly new to Panama’s diverse population, U.S. migration generated new tensions. Initially, American travelers crossed by river and trail, relying on Afro-Panamanian guides and boatmen. Such dependence on black labor was familiar to Southern whites, but for many Northerners it was their first significant contact with people of African descent. Even without firsthand experience, however, they drew upon familiar racial assumptions. When he crossed in December 1849, for example, Wells complained bitterly about prices in Chagres and fantasized about murdering one “old ...