“If you’re going to eat chips, eat Old Dutch. Think globally, eat chips locally.”

—ACE BURPEE, WINNIPEG FREE PRESS, 2009—

Old Dutch Foods is a manufacturer of potato chips with production and distribution across Canada. Many western Canadians believe the company to be a Winnipeg business, though they are owned by a family in Minnesota. An American company, Old Dutch Foods Incorporated, was founded first. The company’s homepage stated, “Since 1934 we’ve delivered the finest snacks, fresh from the heart of the Upper Midwest. We make them close by so they’re guaranteed fresh.”1 The Canadian company, Old Dutch Foods Limited, was founded later as a separate company in Winnipeg, albeit under the same ownership. Their website claims, “It all started in Winnipeg in 1954—most Winnipeggers didn’t even realize that the Old Dutch brand was their own.”2 Does it matter to Canadians if snack foods are manufactured in Canada by Canadian companies owned by Canadians? What, exactly, does it mean for a snack food to be “Canadian”?

Scholars, journalists, and politicians alike have long debated the perceived importance of Canadian ownership of businesses—in other words, the significance of economic nationalism. Thomas Naylor’s 1975 classic, The History of Canadian Business, provides a careful analysis and critique of the changing percentage of foreign ownership in various sectors of the Canadian economy.3 In his excellent introduction to the Carleton Library edition of Naylor’s work, political economist Mel Watkins notes that, more recently, the focus of Canadians has shifted from foreign ownership to corporate globalization, though, ten years ago, it was primarily non-academics who were discussing these issues.4

Symbolic forms of economic nationalism—that is, the use of nationalist myths and symbols to brand a company and sell products—also have a long history in Canada. Paula Hastings demonstrates that, as early as the late nineteenth century, manufacturers were more potent purveyors of English Canadian nationalism than were politicians, intellectuals, or cultural events.5 A century later, the connection between marketing and nationalism was strengthened in the wake of the 1988 Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Canada.6 Given Canadians’ increasing access to American consumer goods, Catherine Carstairs explains, consumer nationalism in Canada tends to emphasize Canada-branded rather than made-in-Canada goods.7 Taking a social (rather than economic) history approach, Patrick Cormack and James Cosgrave argue that companies like Tim Hortons have promoted themselves as “the cultural site for the articulation of Canadian values.”8 Old Dutch potato chips, then, must be seen in the context of these larger debates about what constitutes Canadian identity in the business realm.

The consideration of Old Dutch raises questions as well about whether there is value in distinguishing between large businesses (defined by Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada as those with more than 500 employees)9 and multinationals. Multinationals and large corporations have come under increasing criticism.10 Once a company like Old Dutch reaches a certain size, do they conduct business any differently from large global conglomerates? Are their practices any more generous, any more informed by local conditions?

Origins

Old Dutch potato chips trace their origin back to 1934, when Carl J. Marx founded the Old Dutch Products Company in St. Paul, Minnesota. According to Peter Carlyle-Gordge, in a Winnipeg Free Press article, he chose the name “Old Dutch” because “he associated the Dutch with long-standing cleanliness and quality.”11 Marx prepared chips in his own home: he fried them himself, enlisted the aid of a woman to package the chips, and distributed them to area businesses in his passenger car. By 1937, the business had expanded, and Marx was able to relocate to 412 South Third Street, Minneapolis, where he employed twenty-five workers.12 The company was negatively affected by rationing in the Second World War. Shortly after the war, Marx changed the business name to Old Dutch Foods, since “Old Dutch Products” was too often confused with the popular Old Dutch Cleanser. In 1951, Marx’s health was in decline, so he sold the company to Vernon Aanenson, a certified public accountant, and Arthur C. Eggert, Aanenson’s business partner, for approximately $200,000.13 Aanenson later described how he came to acquire the forty-employee business: “I was having lunch at the Covered Wagon restaurant with an acquaintance, when a fellow by the name of Charlie Skinner came up to me and said he heard that I was looking to acquire a business. I said, ‘maybe.’ That’s when he told me that the owner of a potato chip company, Karl [Carl] Marx was his name, was looking to sell his company. On August 1, 1951, I got into the potato chip business.”14

Old Dutch Foods expanded under the new ownership. A year after purchasing the business from Marx, Aanenson and Eggert bought the potato chip division of the Potato Products Company of East Grand Forks, Minnesota, which sold chips under the Scotts brand.15 In 1954 or 1955, Old Dutch was approached by L&M Distributing, a candy and tobacco company in Winnipeg operated by Joe Lamonica and Vern Miranda, who asked to distribute chips in that city. For a time, L&M used Miranda’s mother-in-law’s basement as their warehouse.16 Four years later, the popularity of Old Dutch chips in Winnipeg was such that it made more sense to open a factory there rather than deliver chips from Minnesota. The Winnipeg plant opened in 1959, and in 196517 Vernon Aanenson became sole owner of the company, which he incorporated in the United States as Old Dutch Foods Incorporated and in Canada as Old Dutch Foods Limited.18 That same year, the American factory moved from downtown Minneapolis to the suburb of Roseville. A second Canadian factory opened in Calgary in 1970.19

With the death of Vernon Aanenson in 1998, management and ownership of the company was left in the hands of his sons, Steven (Steve) as president and chief executive officer, and Eric as vice-president and chief operations officer. Both sons had earned physics degrees from the University of Minnesota; Eric had worked on lasers at Lockheed, and Steve had worked in the aerospace industry at Ball Corporation. Eric, in particular, was pleased to shift to a management position at Old Dutch. As reported by Bernard Pacyniak in an article in Snack Food, Eric had experienced “growing dissatisfaction with the rampant bureaucracy prevalent at Lockheed.”20 At the turn of the millennium, Old Dutch had approximately 1,300 employees and a quarter of a billion dollars in sales; 500 of these employees were in Canada (180 of them in Manitoba) and most of the sales (more than $140 million) were made in Canada.21 The company was named one of Manitoba Business magazine’s Top 100 businesses in 2005.22

Figure 1. Old Dutch delivery van, Roseville, Minnesota, 2013.

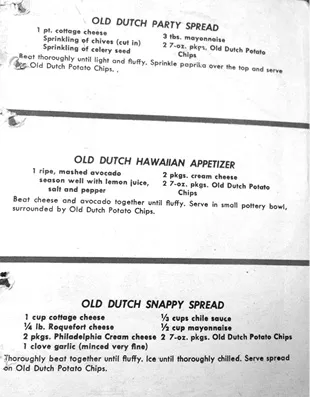

Figures 2–3. Old Dutch Foods recipe book, c.1951.

The company’s Canadian and U.S. websites both emphasize the national and regional identity of Old Dutch: the U.S. website promotes the company as Midwestern; the Canadian website pushes the Winnipeg connection.23 The U.S. corporate head office is in Saint Paul, and American manufacturing plants are located in Roseville and Minneapolis. The Canadian head office (which is also the accounting office) is in Winnipeg; the Canadian sales and marketing office is in Calgary. The business expanded into eastern Canada in 2007 through the acquisition of Humpty Dumpty Snack Foods. As a consequence, the company’s Canadian manufacturing plants now extend across the country: in Airdrie and Calgary, Alberta; Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Hartland, New Brunswick.24 This nationwide distribution is the culmination of a long-held dream: Vernon Aanenson stated in 1959 that he expected “to distribute Old Dutch products across all of Canada eventually.”25 The company attributes their success to a distribution system of branch offices that also contain warehouse facilities, thus ensuring rapid delivery to retailers well before expiry of the products’ ninety-day shelf life.26

The size and scale of Old Dutch undoubtedly require a degree of professional management. The company is nonetheless distinguishable in this respect from global corporations like Frito-Lay, reported by Andrew Smith in The Business of Food to be the “largest snack food conglomerate in the world.”27 The company has a very flat management structure with few layers, both in Canada and in the United States. Management discussions tend to be informal, involving whomever is necessary, rather than conducted as formal board of director meetings.28

Taste

Potato chips, when first commercially produced in the early twentieth century, were unflavoured—just thin slices of potato, fried and salted. By the 1950s, flavoured potato chips had been introduced. In 1959, half the potato chips produced in the Old Dutch plant in Winnipeg were flavoured.29 Old Dutch made only six types of potato chips back then: barbecue, hickory-smoked, pizza, onion and garlic, ripple, and plain (unflavoured). Seasoning was sprinkled on “in powder form after the chip has been fried”—a labour-intensive practice, according to a Minneapolis Star article.30 The company claims to be the first to introduce the popular sour cream an...