![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: AMERICAN POWER AT THE GLOBAL FRONTIER

It is by the combined efforts of the weak, to resist the reign of force and constant wrong, that in the rapid change but slow progress of four hundred years, liberty has been preserved and finally understood.

—Lord Acton

What is the value of allies at the outer frontier of American power? Since the end of the Second World War, the United States has maintained a network of alliances with vulnerable states situated near the strategic crossroads, choke points, and arteries of the world’s major regions. In East Asia, Washington has built formal and informal security relationships with island and coastal states dotting the Asian mainland: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, as well as midsized offshore powers Japan and Australia. In the Middle East, it has maintained a special relationship with democratic ally Israel and security links with moderate Arab states Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates (UAE). And in East-Central Europe, in the period since the Cold War, the United States has formed alliances with the group of mostly small, post-communist states—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria—that line the Baltic-to-Black-Sea corridor between Germany and Russia.

Figure 1.1. U.S. frontier allies worldwide.

Despite their obvious geographic and political dissimilarities, these three regional clusters of U.S. allies share a number of important strategic characteristics (see figure 1.1). All are composed of small and midsized powers (most have between five and fifty million inhabitants and small landmass). Most are democracies and free market economies deeply invested in the Bretton Woods global economic and institutional framework. All, to a greater extent than other U.S. allies, occupy strategically important global real estate along three of the world’s most contested geopolitical fault lines. Most sit near a maritime choke point or critical land corridor: the Asian littoral routes (South China Sea, North China Sea, Sea of Japan, Straits of Taiwan, Straits of Malacca); the Persian Gulf and eastern Mediterranean; and the Baltic and Black Seas and space connecting them that underpins the stability of the western Eurasian littoral.

Perhaps most important from a twenty-first-century U.S. strategic perspective, all these allies are located in close proximity to larger, historically predatory powers—China, Iran, and Russia, respectively—that are international competitors to the United States and within whose respective spheres of influence they would likely fall, should they lose some or all of their strategic independence. None of these states is militarily powerful; with the important exceptions of Japan and Israel, they lack a realistic prospect for military self-sufficiency in any protracted crisis. As a result, all look to the United States, either explicitly or implicitly, to act as the ultimate guarantor of their national independence and security provider of last resort.

The view has begun to take root in the United States that these sprawling alliances are a liability—either because of the costs that they impose through the necessity of maintaining a large military and overseas bases or because of the perils of entrapment in conflicts involving faraway disputes. Maintaining extensive, expensive, and binding relationships with exposed and militarily weak states located near large rivals, we are told, will cause more problems than they are worth in the geopolitics of the twenty-first century. Citing nineteenth-century Britain’s alleged aloofness to foreign states, domestic critics of alliances counsel Washington to spurn continental commitments to small and needy allies. Echoing Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck, these critics warn that the United States must avoid intervening in conflicts that aren’t “worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier,” whether that conflict be in Estonia or in the South China Sea.

But these views are wrong—and dangerous. For the past sixty years U.S. foreign policy has pursued exactly the opposite course, and for good reason. The United States has deliberately cultivated bilateral security linkages with small, otherwise defenseless states strewn across the world’s most hotly contested regions, militarily building them up and even providing overt guarantees to them. In fact, it has often seemed to value these states precisely because of their dangerous locations. During the Cold War America’s overriding imperative of containing the Soviet Union lent geopolitical value to relationships with even the weakest allies, which in turn utilized U.S. support to strengthen regional bulwarks against the spread of communist influence. In the unipolar landscape that followed, the United States surprised many foreign policy analysts by not only not dismantling this globe-circling alliance network (as would be expected of a great power after winning a major war) but actually expanding it through the recruitment of new allies from among the former communist zone of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). In both structural environments, allies have been the “glue” of the U.S.-led global order: in the Cold War by containing the Soviet Union and in the post–Cold War period by sustaining the benefits of stability and prosperity that the Cold War victory helped to create.

These alliances have not been cheap for America to maintain, in either financial or strategic terms. To a greater extent than in relationships with large, wealthy, insulated states like Britain, Germany, or Australia, American patronage of frontier states like Poland, Israel, and Taiwan entails potential strategic costs, insofar as such states lie at the outer reaches of American power and require recurrent demonstrations of physical support vis-à-vis would-be aggressors. To underwrite the independence and security of these states, the United States has for decades made available a wide array of support that includes both “normal” alliance mechanisms—formal or informal security guarantees, military basing, coverage under the U.S. nuclear umbrella—as well as other special forms of support targeted to the needs of these states, such as military funding, troop exercises, forward naval deployments, technology transfers, access to special U.S. weapons, and various forms of economic, political, and military aid. In the diplomatic realm, Washington has paid a kind of “sponsorship premium” for these states, providing backing and support in the regional disputes in which many inevitably find themselves embroiled. The more exposed the ally, the higher this sponsorship premium is.

Not surprisingly, critics of an active U.S. foreign policy have often complained about the expense and risk required for maintaining these alliances.1 But despite this criticism, America’s commitment to these states has remained steady for the better part of seventy years, making it one of the most consistent tenets of modern U.S. foreign policy. And in both strategic and economic terms, it would be hard to argue that the United States has not gotten a good return on this investment. By exerting a strong, benign presence in formerly unstable regions, U.S. patronage of alliances in East Asia, the Middle East, and East-Central Europe has helped to contain and deter the ambitions of large rivals, suppress regional conflicts, keep crucial trade routes open, and promote democracy and rule of law in historic conflict zones. In East Asia, the U.S. presence facilitated pathways of financial investment that contributed to the creation of some of the world’s most dynamic economies and major engines of global growth while guarding the sea-lanes through which the majority of U.S.-bound energy supplies and consumer goods pass. In East-Central Europe, U.S. efforts to propel NATO and European Union (EU) expansion effectively eliminated the geopolitical vacuum that had helped to generate the conditions for three global wars in the twentieth century—two hot and one cold. And in the Middle East, U.S. engagement has helped to contain regional cycles of instability and prevent their spillover into global energy markets and the American homeland. In both the bipolar and unipolar international settings, allies have been indispensable to maintaining the global order that has allowed for the peace and prosperity of the “American” century.

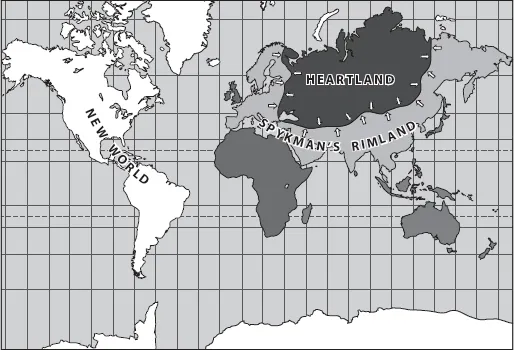

Part of the reason U.S. patronage of states in these regions has been so successful is that U.S. allies and potential challengers have understood that it is unlikely to change suddenly, in large part because of how deeply encoded in contemporary American strategic thinking has been the support of small allies. Since the turn of the twentieth century the United States has invested its strategic resources in a combination of naval power and, after two world wars, “defense in depth” through a presence in the Eurasian littorals—what the mid-twentieth-century American strategist Nicholas Spykman called the global “rimland” (see figure 1.2). This pattern of forward engagement is not only the basis for American investment in allies located in the three hinge-point regions, it is a central tenet of U.S. foreign policy. Building on this foundation, America, though primarily a maritime power like Britain, has avoided the island dilemma of being perceived as fickle, retiring, and unreliable—in short, of becoming a second “perfidious Albion.”

Figure 1.2. Spykman’s rimlands.

Source: Mark R. Polelle, Raising Cartographic Consciousness: The Social and Foreign Policy Vision of Geopolitics in the Twentieth Century (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 1999), 118.

But there are signs that America may be beginning to rethink its approach to alliances. In recent years U.S. policy makers’ view of the relative costs and benefits of maintaining far-flung small-ally networks has begun to shift. The change is partly fueled by adjustments in global geopolitics and the “rise” or resurgence of revisionist states, many of which claim to have historic spheres of influence that overlap with the regions where America’s alliance obligations are highest and its strategic reach most constrained. Another driver has been the changing U.S. economic landscape and constraints on the U.S. defense budget, which call into question whether the United States will continue to maintain the force structures that have made its geographically widespread alliances possible to begin with. Finally, and perhaps most important, Washington appears to be deprioritizing many of its longest-standing relationships with traditional allies in pursuit of grand bargains with large-power rivals, if necessary over the heads of its allies.

The net effect of these changes in the geopolitical, economic, and political realms has been to challenge the central paradigm on which the United States has based its strategy for managing global alliances since the Second World War. What value do alliances hold for America in the twenty-first century? Do the benefits of alliances that led the United States to accumulate them during bipolarity and unipolarity still apply under conditions of contested primacy? How does a great power that has accumulated extensive small-power security commitments maintain them when the geopolitical landscape becomes more competitive? What do geopolitically vulnerable allies like Israel, Poland, or Taiwan have to offer America amid the rise of large powers? Is it still worth paying the economic and strategic costs to provide for their security? If so, how should the United States rank the importance of the weapons, bases, and funding that sustain these alliances alongside other national security priorities in an era of constricted budgets? Would the United States be better off reducing its commitments to these states and maintaining a freer hand in global politics, as critics claim?

These are the kinds of questions that are likely to confront American diplomats and strategists with growing frequency—and urgency—in the years ahead, as the shift from the post–Cold War global order accelerates. Such questions are not new in the history of international politics, but they are relatively unfamiliar to the U.S. policy establishment, which has arguably not had to reexamine the fundamentals of American grand strategy in many decades. In recent years Washington has been slow to study the geopolitical changes that are under way in the world and respond to them in a strategic way. Increasingly the U.S. foreign policy agenda seems to be driven by a combination of crisis management—Iran, Syria, North Korea—and a political agenda that takes the basic contours of the U.S.-led international system for granted and focuses on achieving laudable but unrealistic and outright silly goals, such as global nuclear disarmament. Both approaches tend to magnify the apparent advantages of partnering with large powers on ad hoc issues as the preferred template for U.S. foreign policy over the near term while deferring for a later day bigger questions about how to sustain U.S. leadership in the international order.

But American grand strategy cannot remain on autopilot forever—geopolitics is forcing its way onto the agenda. Rivals and allies of the United States alike perceive that changes are afoot in America’s capabilities and comportment as a great power and are responding purposefully to the opportunities and threats that these changes present. This is partly driven by the hypothesis of American “decline.” In many of the world’s capitals, it is taken as an article of faith that the United States is slipping from its decades-long position of global preeminence and that the long-standing U.S.-led international system will eventually give way to a multipolar global power configuration. It is also driven by the perception that, declining or not, the United States is simply not interested in maintaining the stability of frontier regions—that the alliances it inherited from previous eras will be a net liability in an age of more fluid geopolitical competition.

U.S. retrenchment from these regions creates a permissive environment for rising or reassertive powers. All three of America’s primary regional rivals—China, Iran, and Russia—possess prospective spheres of influence that overlap with America’s exposed strategic appendages in their respective regions. Should China manage to co-opt or coerce the foreign policies of the small littoral states surrounding it, Beijing would be able to alleviate pressures on its lengthy maritime energy routes, shift strategic attention to the second island chain, and focus more on landward expansion. Similarly, should Russia, for all its economic backwardness, manage to reinsert its influence into the belt of small states along its western frontier, Moscow could consolidate its commanding position in European energy security, regain access to warm-water ports, and stymie NATO and EU influence east of Germany. Should Iran manage to gain greater influence among its small Arab neighbors, particularly those along the Persian Gulf coastline, it would be able to enhance its ability to disrupt international oil supplies.

In all three cases, America’s rivals stand to gain in potentially significant ways from U.S. retrenchment. But these powers face a dilemma. While they may sense that changes are under way in the international system and even imagine enlarged opportunities to revise the status quo, they don’t want to incur the potentially high costs of a direct confrontation with the United States. Sensing an opportunity, they want to revise the regional order, but they are uncertain about the amount of geopolitical leeway they have and therefore the degree of license they can take in safely challenging the status quo. From the standpoint of these revisionist powers, the United States may be in retreat, by choice or necessity, but it is unclear by how much. And this makes it risky to pick a direct fight. Even in the era of sequestration, America retains many hegemonic capabilities and characteristics—including the forward-deployed system of alliances and security commitments that America continues to maintain in their own neighborhoods—that present real obstacles to aspirant powers.

Rising powers therefore have an incentive to look for low-cost revision—marginal gains that offer the highest possible geopolitical payoff at the lowest possible strategic price. That means not moving more aggressively or earlier than power realities will allow. And that, in turn, requires getting an accurate read of global power relationships. How deep is the top state’s power reservoir? How spendable are its power assets? How determined is it to use them to stay on top? And how committed is it to defending stated interests on issues and areas that conflict with the riser? Would-be powers need to understand the likely answers to these questions before they act.

Historically, rising powers faced with this dilemma have found creative ways to gauge how far they can go in a fluid international system before encountering determined resistance of the leading power. One way would-be revisionists have done so historically is to employ a strategy of what might be called “probing”—that is, using low-intensity tests of the leading power on the outer limits of its strategic position. The purpose is both to assess the hegemon’s willingness and ability to defend the status quo and to accomplish gradual territorial or reputational gains at the expense of the leading power if possible. These probes are conducted not where the hegemon is strong but at the outer limits of its power position, where its commitments are established (and potentially extensive) but require the greatest exertion to maintain. Here, at the periphery, the costs of probing are more manageable than those of confronting the hegemon directly, which could generate a strong response by the leader.

Probing, though not widely studied, is the natural strategy for many revisionist powers. This was the technique a rising imperial Germany used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as it concocted low-intensity diplomatic crises to test British resolve and alliances in various regions. There is growing evidence to suggest that the rising and resurgent powers of the twenty-first century are using this same strategy. The Russo-Georgia War (2008), the Hormuz Straits crisis (2012), the Senkaku Islands dispute (2013), the Ukrainian War (2014–present), the Baltic Sea air and naval tensions (2015), and the Spratly Islands confrontations (2015) are all examples of an increasingly frequent category of strategic behavior by revisionist powers to assess U.S. strength and level of commitment to defending the global security order. Although the exact nature of the tools involved in these crises may differ, the basic principle is the same: to a...