![]()

Chapter

1

The Provenance and Ramifications of the SCS Conflicts: Law, Resources, and Geopolitics

The South China Sea (SCS) may, by common sense, be assumed to be part of the Pacific Ocean. But, in this book, we treat it as a separate body of waters in its own right, due to its distinctive status arising from a combination of four peculiar factors: (a) its vital importance as a hubbub of trade, since one-third of the world’s shipping (valued at $5.3 trillion in 2015) sails through its waters; (b) its abundant resources, including oil and natural gas; (c) the wide attention it commands because of the clashes arising from the neighboring nations’ overlapping sovereign claims; and (d) post-2010 U.S. geopolitical interests in the region as a strategic site of rivalry with the rerising China, although largely dressed as a freedom of navigation dispute.

For amplification of (a) above, let me add that the oil transported through the Malacca Strait through the Indian Ocean en route to East Asia via the SCS is triple the amount that passes through the Suez Canal, and 14 times that through the Panama Canal.1

This body of waters, stretching over 1.4 million square miles, has been the locale for activities of, or interactions between, the surrounding societies going back to prehistorical times, through the Western colonial dominance in the region (dating from the 16 th to the mid-20th century), down to the post–Cold War era. Unlike in the East China Sea disputes, through much of this long stretch of time the SCS, surprisingly, had its share of relative peaceful tranquility. Exceptions were found in the past strife associated with the intrusion of Western colonialism and, more notably, the truculent inroads by the Japanese Imperial Army (1930s to 1945).2 Even the assertion by the parties of their competing claims, in the past, was relatively muted, by comparison. But, in more recent years, this maritime scene has become a tinderbox of explosive international tensions of rising magnitude, largely for two reasons, namely: (a) the salience of the newly identified abundance in oil deposits among other resources in SCS and (b) the spillover of the United States’ Asia Pivot policy. The following discussion will tackle each of these points separately, in greater depth.

Highlight on SCS Resources: Competing Claims

A 1968 U.N. report revealed the discovery of rich oil and natural gas deposits in the SCS, according to one source.3 This was echoed by a tweet on a Chinese blog, calling the SCS the “second Persian Sea” in reference to its vast oil deposits.4 The Council on Foreign Relations in New York gave a more modest, but still staggering, estimate: some 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas deposits under the subsoil of the SCS.5

It may not be coincidental that the conflicts with China by some Southeast Asian contending neighbors, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, began to hike in the years immediately following 1968. For instance, the struggle over the Paracels between Vietnam and China began in 1970; and a war broke out in 1974, in which Vietnam was defeated, and China took back the complete control of the island group. On its part, the Philippines in 1971 announced its claim to islands in the Spratlys adjacent to its territory, which it renamed Kalayaan and incorporated into Palawan Province the following year.6 On March 11, 1976, the first Philippine oil company “discovered” an oilfield off Palawan island. Also in the 1970s, the Philippines, Malaysia, and other countries began referring to the Spratly islands as included in their own territory. President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, for example, issued Presidential decree No. 1596, on June 11, 1978, declaring the Spratlys (referred to as the Kalayaan Island Group) as Philippine territory.7

To bring things up to date, the search for oil even brought India and Japan to the SCS, by means of cooperative deals signed with Vietnam in the early 21st century. On July 22, 2011, an Indian amphibious assault vessel, the INS Airavat, on a friendly visit to Vietnam, was contacted, some 45 nautical miles off the Vietnamese coast, by the Chinese navy that it was entering Chinese waters.8 In reply, the Indian side quipped that seeing no ship or aircraft in view, the INS Airavat just proceeded on her onward journey as scheduled. Citing freedom of navigation, it continued that the Indian vessel meant no harm or confrontation.9 In September 2011, shortly after Vietnam and China had signed an agreement seeking to contain a dispute over the SCS,10 India announced that ONGC Videsh Ltd, an Indian overseas investment company, had signed a three-year agreement with PetroVietnam for developing long-term cooperation in the oil sector. The announcement also said that India had accepted Vietnam’s offer of exploration in certain specified blocks in the SCS.11

Vietnam and Japan, early in 1978, also reached an agreement on the development of oil in the SCS. By 2012, Vietnam had concluded some 60 oil and gas exploration and production contracts with various foreign companies.12 There are reports that show that Vietnam, which used to be an oil-poor country, had an average production of 298 barrels of crude a day (298 BBL/D), during 1994–2016, making it an oil exporting country.13

As if not to be left behind, China’s first independently designed and constructed oil drilling platform in SCS, Ocean Oil 981 (海洋石油 981), also began its first drilling operation in 2012. The platform is located 320 km (c. 200 miles) southeast of Hong Kong.14

China’s Connections: An Inherent Link to a Historic Waters Claim

After waiting out a period of hesitancy in the face of the Vietnamese and Philippine challenges, noted earlier, China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) passed a “Law on Territorial Waters and Adjacent Regions” in 1992. The Law formalized the People’s Republic’s 1958 “Proclamation on the Territorial Sea.” I wish to stress that for a true understanding of their legal and practical significance, these two documents must be read in the light of a map made by the Chinese in 1947, two years after the end of World War II (WWII), from which China under the Chiang Kai-shek government emerged as a victor power, on the side of the Western WWII Allies.

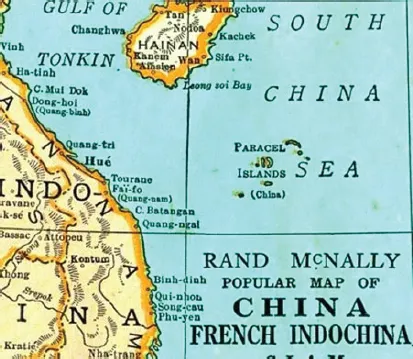

While China’s claim to the SCS goes back to the pre-Christian era (more details in Chapter 2), the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII occupied the major island groups, including Paracels and Spratlys. Under the Cairo Declaration (November 1943) and the Potsdam Declaration (July 1945), however, the WWII Allies agreed on a demand for the soon-to-be-defeated Japan that it must surrender (and return) all territories it had pilfered (“stolen”) from their original owners. Hence, after the war, the Republic of China (ROC), under Chiang Kai-shek, recovered these islands from the Japanese in 1946, with the logistical (naval) support from its U.S. ally.15 After regaining control of the SCS, the ROC government in 1947 drew an 11-dash line map delineating the maritime extent of Chinese control of the waters (including the islands) of the SCS. The map was known as “Map of South China Sea Islands.”16 It followed a much earlier “Map of Chinese Islands in South China Sea” (Zhongguo nanhai daoyu tu), published by the ROC’s Land and Water Maps Inspection Committee in 1935.17 The 1947 map showed the extent of China’s historic title over most of the maritime region in the SCS, and in international law it would come under the concept of “historic waters” (see discussion in Chapters 2 and 3). See the following map:

It should be noted that this map, showing the Chinese U-shaped line, resembling a cow’s tongue, indicates that China does not claim the entire SCS, as alleged by almost every critic and accuser of China’s “assertive” claim. The space in between the U-shaped broken line and the putative coastlines of the surrounding states, such as today’s Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines, clearly manifests an allowance for the territorial seas that they may opt to claim (after they emerged from colonial rule).

Figure 1.1(Internet Photo)

Apparently, this relative self-restraint may have been a reason why the map did not draw any international objection at the time. Another reason was that “historic waters” was a concept accepted by the prevailing international law at the time.

It is noteworthy that the Chinese map was immediately adopted in the 1947 edition of the Rand McNally Map of China, as shown in Figure 1.2, suggesting instant international recognition.

Figure 1.2“China” is Shown Underneath the Paracel Islands in Parenthesis on the Map Made by Rand McNally in 1947. (Internet Photo)

After the Communists took power in China in 1949, the new People’s Republic of China (PRC) government adopted the 11-dash line but reduced it to nine, eliminating the two dashes most adjacent to the Gulf of Tonkin as a gesture of friendship toward Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam. After evacuating to Taiwan after losing the civil war on the mainland, the ROC government (now resettled in Taiwan), nevertheless, continues its claim to the SCS as before, but used the coopted name of the 9-dash line (rather than the original 11-dash line), in support of its claim.18

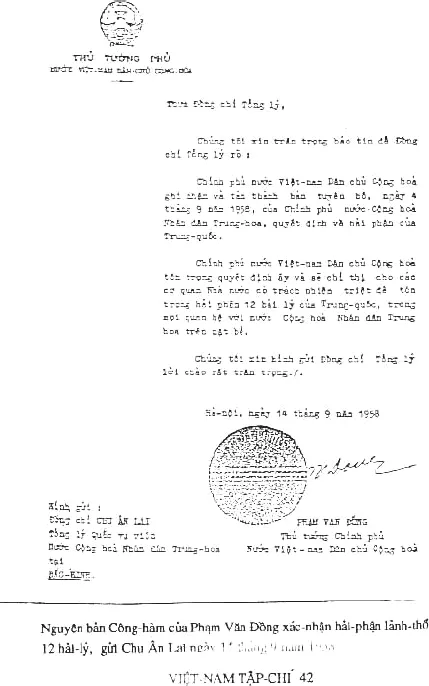

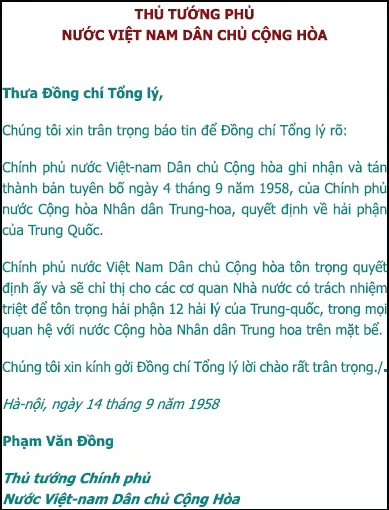

As mentioned earlier, the Government in Beijing, on September 4, 1958, issued the Proclamation regarding the breath of China’s territorial sea, which extended 12 nautical miles seaward from the China coast. It stated that the rule applied to “all Chinese territories, including … the Dongsha islands [Pratas], the Xisha Islands [Paracels], the Zhongsha Islands [Macclesfield Bank], the Nansha Islands [Spratlys] …” (emphasis added). Ten days later, in an official note to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, the Vietnamese Prime Minister, Pham Van Dong, declared “the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam recognizes and supports the declaration of the Government of the People’s Republic of China’s territorial sea made on September 4, 1958.” (Pham Van Dong’s letter written in Vietnamese, reproduced below.19)

Special attention should be paid to this 1958 documentary evidence, attesting to the official Vietnamese government’s explicit recognition that the “Chinese territories” included the Paracels, which is now claimed by Vietnam in competition. The obvious reason is a hidden struggle for the oil resources near the Paracel island group. The conflict surfaced in early 2014 when the Chinese moved its Ocean Oil 981 oil rig to the territorial waters of the Paracel island group, which even by the Vietnamese Premier Pham Van Dong document should be within China’s territory. In its wake, however, Vietnamese anti-Chinese protests boiled over, from mob rioting, ransacking, to torching of Chinese (and other Asian but mistaken to be Chinese) factories and companies in different parts of Vietnam. Among rampant reactions worldwide, the U.S. State Department sided with the Vietnamese and blamed the violence and carnage on Chinese “unilateral action [that] appears to be part of a broader pattern of Chinese behavior to advance its claim over disputed territory in a manner that undermines peace and stability in the region.”20

Figure 1.3

U.S. Support Stiffening the Backbone of China’s Competitors

The other reason why the SCS conflicts spiked after ...