![]()

PART I

After Peace

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Theatrum Pacis

Mediating the Treaty of Karlowitz

When and where does one find peace? Peace, if it is ever established, has a fleeting existence, and thus writing its history invariably becomes a historiography of conflict and war. In spite of the challenges posed by representing peace, it plays a vital role in this book’s consideration of European descriptions of the Ottoman world in the eighteenth century. As we will see, the intermittent cessation of hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and its neighbors throughout the century had a deep impact on what I am going to loosely call an art of engagement. Engagement is a valuable word here because it has both geopolitical and aesthetic connotations, and this book will repeatedly make the transit from one to the other of these meanings. This chapter is about the mediation of the single most important interaction between Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the history of both domains. The Treaty of Karlowitz of 26 January 1699 fundamentally altered the rules of engagement for diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and its European neighbors. In the words of Mehmet Sinan Birdal, “the signing of a peace treaty with a Christian state and the adoption of an international rule represented a radical break with imperial unilateralism. The ensuing treaties, which were negotiated for the first time by Ottoman diplomats of scribal rather than military origin, set clearly demarcated political boundaries and imposed respect for territorial integrity.”1 As this chapter unfolds we will be attending to the role played by Lord William Paget, the English ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and Jacobus Colyer, his Dutch counterpart, in mediating this epochal agreement between the Holy Roman League and the Ottoman sultan. But my analysis of their actions cannot be separated from how the treaty negotiations were mediated for European audiences. Thus I will be considering “mediation” in two senses of the word. In order to comprehend diplomatic mediation we will be looking at its representation in scribal networks, official and unofficial correspondence, newspapers, pamphlets, maps, engravings, and illustrated books. My primary objective is to use this informational archive, especially the interaction of text and image, to understand a repertoire of particularly auspicious intercultural performances—performances that quite literally changed the world.

The year 1699 is frequently invoked as the beginning of the decline of the Ottoman Empire in that the treaty marked the end of its westward expansion. The fact of the matter is that the borderlands in eastern Europe remained very much in contention for the first half of the eighteenth century, and the Ottoman Empire itself remained a significant territorial power for a further two hundred years.2 But 1699 marked a moment of transition, both historical and representational, in relations between the Ottoman world and Europe.3 The Treaty of Karlowitz was the first diplomatic engagement in which the Ottomans were not negotiating from a position of strength. In prior treaty negotiations, the Ottomans were victorious in the field and merely sent representatives from the military to dictate terms.4 This peace was also the first negotiated by civil servants: the Ottoman delegation was composed of the reis efendi, referred to in European publications as the secretary of state, and the chief dragoman, or interpreter, to the grand vizier.5 The activities of these two men inaugurated a new era in Ottoman diplomacy and governance in which the Ottomans seemingly accepted the basic structural principles of international law promulgated in the post-Westphalian era.6

This was a conflict and a negotiation between empires with radically different legal histories and styles of legitimation that were slowly transforming into absolutist states.7 Birdal emphasizes that the Habsburg and the Ottoman Empires transformed from self-declared global imperial powers to absolutist states according to very different chronologies.8 At the time of the Treaty of Karlowitz, the Habsburgs were effectively an absolutist monarchy with residual links to the other states in the Holy Roman League. The Ottomans retained the posture of universal empire throughout the eighteenth century and only began the full transformation to an absolutist state form in the nineteenth century.9 This makes the legal procedures adopted during the Treaty of Karlowitz quite complex. The Ottomans came to the table accepting the principle of uti possidetis—that is, that the various parties to the treaty would retain territories captured during the war—but the very notion, derived from Roman law, was translated to suit an Ottoman view of world affairs. Provisional acceptance of this principle did not imply that the Ottomans thought they were negotiating with equally sovereign powers—there was no recognition of foreign sovereignty. And it is clear from Abou-El-Haj’s analysis of Rami Mehmed Efendi’s “relation” of the negotiations that the Ottoman negotiator was working from a fundamentally different understanding of the preliminary agreements: one that understood the agreed-to procedures, principles, and evacuation clauses in ways that were in keeping with past modes of Ottoman negotiation and state legitimation.10 What we have then is an act of political and legal mistranslation that enabled the Ottomans to retain their own self-image in a seemingly post-Westphalian situation. One could argue that the entire negotiation operated much like a Lyotardian “differend,” where mutually exclusive phrase regimes were brought together in a way that enabled a kind of improvisatory interface between these state forms.11

The protracted war with the Holy Roman League that included Austria, Poland, Venice, and Russia dated back to the final months of 1682 and was, on the whole, a period of substantial loss for the Ottomans. The war started with the failed siege of Vienna in 1683, and its end was precipitated by the catastrophic Battle of Zenta in 1697. On 27 September 1697 readers of the newspapers in London would have encountered the following supplement dated Vienna, 14 September:

The Emperor has received advice by several Expresses of a signal Victory obtained by his Army over the Turks, on the 11th instant, near Zentha, with the following particulars: Prince Eugene of Savoy being reinforced with 7000 men from Transylvania, under the command of General Rabutin, resolved to fight the Ottomans; and accordingly marched the 9th instant with the Cavalry 18 hours together: the 10th he lay within 2 German leagues of the Turks, and the Foot came up. The 11th day early in the morning he advanced with Prince Vaudemont to view the disposition of the Enemy, and found 24000 Janizaries and 6000 Horse encamped on a very advantageous Post, for the security of which they had cast up three Intrenchments; the main body of their Army being encamped on the other side of the River Theysse; whereupon a Council of War was held, wherein it was resolved to attack the Enemy while they were divided, and immediately the Artillery was posted on a rising ground, with orders to fire upon the Bridge of the Turks, and hinder their passage; and the whole Imperial Army attack’d them with so much vigour, that tho the Intrenchments were defended with 72 pieces of Cannon, they took the first in an hour, and the others [sic] two in 3 hours more. The Slaughter was so great, that 10000 Turks were killed on the spot, with the Grand Visier and the Aga of the Janissaries. The rest endeavoured to get over the Theysse, but they were in such a confusion, that the greatest part were drowned. They left all their Cannon, Baggage and Ammunition. We had about 1000 men killed and wounded. Expresses have been dispatched to the King of England, the States, and the Elector of Bavaria, to acquaint them with this welcom News.12

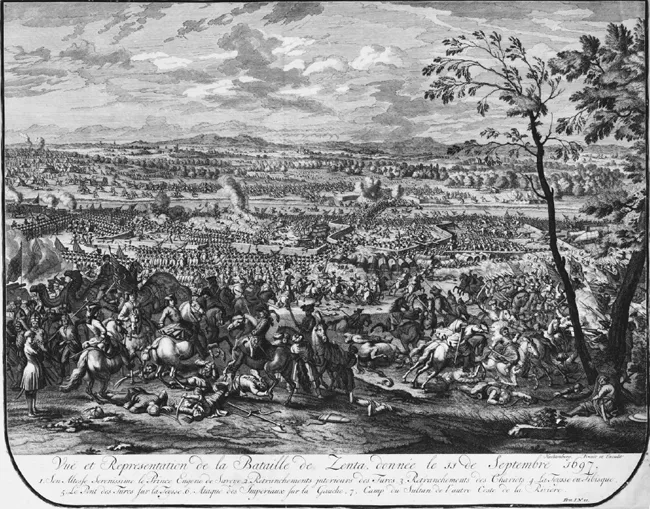

Prince Eugene of Savoy essentially destroyed the sultan’s infantry: between 25,000 and 30,000 Ottoman soldiers, including most of the officer class, lost their lives in a single day of action. Of these dead, up to 20,000 drowned trying to flee across the river Tisa in present day Serbia.13 With the river fully clogged with rotting corpses, the Austrians were forced to relocate their camps to avoid the stench.14 As one might expect, engravings celebrating the near-total victory were immediately put into print that emphasize the sheer number of Ottoman soldiers and cavalry killed by the forces of the heroic prince on horseback. Versions of these images were still being produced in the 1720s (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Jan van Huchtenburg, Vue et representation de la bataille de Zenta . . . 11 Septembre 1697, etching, 1725. Trustees of the British Museum.

The Battle of Zenta prompted “an extraordinary procession” in Vienna and something close to panic in Constantinople: according to letters from Vienna published in the London press, the grand signor “is inconsolable for his defeat which he frequently bewailes with Tears in his Eyes, and ’tis confirmed, that of all his Infantry only 2500 escaped.”15 A subsequent issue of the same paper describes elaborate scenes of self-castigation initiated by the Ottoman sultan, the extremity of which likely points to their fictionality. Declaring that the sultan attributed the loss of 30,000 men to a failure “to attone the anger of God, and appease his great Prophet,” the paper reports that an edict had been issued demanding a multiday fast and specifying that the “Mufty and his Domesticks shall . . . appear first in the open Streets, and afterwards in the Churches in Sackcloth, girt about their Wastes with Ropes, and shall with mournful Countenances, Gestures and lamentable Outcries repeat JA AAGIB JA ALLAH ALLAH (O Wonderful God! O God.)”16 This is merely the prelude to the following directions for a procession—ostensibly from the sultan—that confirms preexisting European views of Ottoman fanaticism and ferocity, this time turned inward:

A great Chest full of dead Bones, broken Sabres and Muskets shall be carried, by 6000 Persons in Sackcloath, barefooted, without Turbants, and girt about their waste with ropes.

3000 Mussulmen shall sprinkle Blood and Ashes upon the Ground, Crying, Howling, Shreiking, and renting their Garments.

6000 Persons half naked shall scourge their Breasts and Shoulders with Thorns, till their Blood stream out upon the Ground, and it shall not be dried up.

3000 Spahys [spahis] without Turbants shall carry the Chest of the Prophet in the middle of this procession, and 300 Bassa’s [pashas] with naked Sabres, shall go up and down, and if any man presume to stare upon the said Chest, he shall be immediately cut in pieces, and his Body thrown to the Dogs.

At every Miles end a Christian Slave and a Jew shall be cut in pieces, and left to dye wallowing in their Blood.17

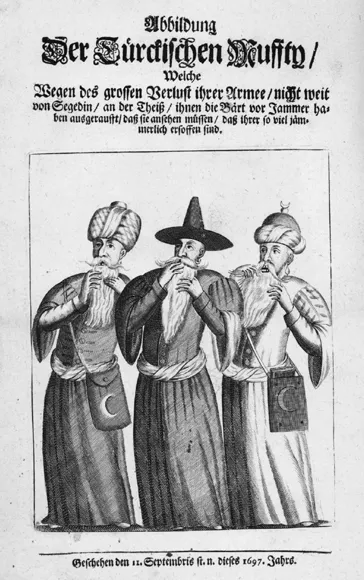

The spectacle of humiliation and staged exculpation fills multiple columns in the paper, and, in spite of the fact that processions were part of the Ottoman political repertoire, it is hard not to read texts like this as a form of wishful thinking on the part of Europeans used to fearing Ottoman aggression in eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Broadsides featuring Ottoman religious officials tearing their beards out in consternation crystallized this scene of abjection (Figure 5).

But this gloating over Ottoman suffering is quickly replaced by reports on the progress of peace:

Vienna, Aug. 23. We hear that the Principal points of the Peace with the Turks viz. That the Principality of Transylvania, and all other Conquests made during this War, shall remain in the Emperors Full Possession, and the Turks keeping of Belgrade, are adjusted by the English Ambassador, the Lord Paget; we will also try to divert the Turks from pretending the demolition of Peterwaradin; but the question is, whether they’ll agree to the dismantling of Temiswar, which the Emperor insists upon; yet it seems that this Peace is look’d on by both parties as good as Concluded.18

Figure 5. Anon., Abbildung der Türckischen Muffty, Welche Wegend es grossen Verlust ihrer Armee, engraving, 1697. Trustees of the British Museum.

The principle of uti possidetis, alahaleh in Ottoman usage, had been proposed on numerous occasions by Paget but was only accepted by the Ottomans in an imperial rescript of July 1697.19 For the Ottomans this would mean giving up Transylvania and other parts of Hungary—vast losses that could only be mitigated by retaining the Banat of Temeswar and certain strategic sites on the newly established territorial limits.20 Working out these limits in a way that saved face for the sultan was the primary task of the Ottoman negotiators.

Coverage of the treaty negotiations in the London press worked by printing letters sent from more proximate sites to the news. In this case, initial reports from Vienna gave way to reports from Belgrade and finally readers in November and December of 1698 started reading accounts marked and dated from Karlowitz.21 These reports are remarkably detailed. For example, the press was especially attentive to the wretched weather. Reporting on the first day of negotiation, the Post Boy for 1–3 December states: “Both Parties have sent away most part of their Guards, retaining only as many as are actually necessary, by reason of the excessive Cold, which occasion’d divers of the Turks to desert, and an Arabian belonging to the Lord Paget died with Cold.” This report ties in with others about Paget’s ill health, but it either arises from a correspondent in the encampment or is meant to give that impression. As the same report indicates, “the Tents were surrounded with a Guard of Imperialists and Turks, with divers Officers of both Nations, who see all, tho’ not hear it.” More substantive remarks pertaining to the actual negotiation itself would seem to arise from the gossip collected by those adjacent to, but not immediately part of, the talks. And some of these remarks are more specific than any of the post-treaty publications: “the chief Debates are about settling the Limits, on which the Turkish Ambassadors desired, That since the Sultan, their Master, renounc’d his Right to a whole Kingdom, and so many Provinces, some insignificant things might be granted them in the Limiting of Frontiers.”22 This is not represented speech, but this summary’s mimicking of the reis efendi’s idiom almost operates as free indirect discourse and thereby feigns a kind of immediacy. Staging moments of immediate witnessing was as much a part of the representational economy of the “news” as it is today. None of the retrospective accounts published after the ratification of the treaty offer this kind of detail...