![]()

1

Sweet on the Inside: Trauma, Memory, and Israeli Cinema

Boaz Hagin and Raz Yosef

The complexities and paradoxes of trauma and memory are no longer a secret in Israeli cinema. Israeli screens are thronged by fiction and documentary films and videos dealing with personal and group traumas and memories and questioning national histories and commemorations. The traumas of victims and victimizers and the darker sides of official history and nostalgic memories are repeatedly exposed. They are tied to war and terrorism; to the horrors of the Holocaust and its aftermath; to the sins of colonialism and racism; to the experience of being uprooted immigrants; to a militarist, homophobic, sexist society; and to attempts to realize conformist utopias in kibbutzim, Ultraorthodox communities, the supposedly meritocratic people’s army, settlements in the Palestinian Occupied Territories, or the hip neighborhoods of Tel Aviv.1

In a certain sense, there is considerable enjoyment in feeling as if one has just unmasked a deep, repressed secret, and many films and film scholars are happy to guide us on such hermeneutic outings into the past.2 Yet, today, too many traumas and memories are far from being repressed in the inaccessible recesses of the unconscious. Israeli popular culture and academic writing are all too familiar with them. Delving into silenced realms of the past can help us to address suffering and wrongs that have remained unacknowledged. However, the trappings of such revelations can also serve political posturing. They can signal attempts by moving-image makers to conform to the formats of local and international television industries and to cater to the demands of distributors of “world cinema.” And they can be used by scholars to apply onto local cinematic texts the latest global fads in the humanities. In Israeli politics, the trauma of the Holocaust is a wildcard that can be used to trump any rival argument and groups can ground their identities in oppressed memories of victimhood while ignoring their responsibility for shaping the present and the future and their own roles as victimizers.3 Traumas and complex structures of memory now risk being over-familiar and being coopted into the bland mainstream where they no longer disturb and can serve politics as usual. Perhaps the trope of depth, with its repressed secrets and dramatic unveilings, has lost some of its sting, but these memories and traumas and the issues they deal with are very real and it is exactly because they can be manipulated so easily and risk inundating us that they merit our vigilance and continued attention. It behooves us as scholars to discover and create new ways of approaching trauma and memory, the beyond or otherwise of facile manipulations of “depth” as revealing the unknown truth.4

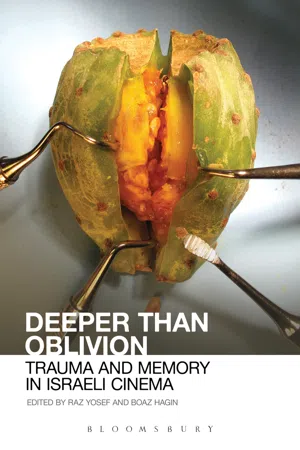

We might start by judging this book by its cover. The image, created by one of Israel’s leading graphic designers and visual artists, Yossi Lemel, is based on a poster of his exhibition titled “Anatomy of a Conflict.” The object being operated upon is the fruit of the prickly pear cactus, known in Israel as sabres or tsabar, and from which the term Sabra, the new Israeli-born Jew, is derived. The sabra fruit is rough and prickly on the outside but sweet on the inside, as, allegedly, are the human Sabras—we can be a tad uncouth and do cut in line sometimes but we are nice once you get to know us. Lemel’s image struck us arousing conflicting interpretations, emotions, and associations that also motivated this collection which seeks to question trauma and memory in Israeli cinema. The sabra in the image is clearly not well—the helpless sabra seems to be bleeding and perhaps undergoing some kind of surgery. It seems to be injured, recalling the Greek term for wound—“trauma.” The metal tools violating its body might be medical devices in the service of healing, but might also be instruments that are being used by a sadistic mad dentist, or scientists dissecting the sabra, prodding its sweet flesh, and putting it on display for our viewing pleasure. The image is also sexually suggestive with the incision creating a vaginal orifice in the violated sabra and bringing to mind the sexual nature attributed to some traumas and repressed memories since the late nineteenth century and the porous borders between prurient voyeurism and scientific inquiry’s will to knowledge. Assuming that the photography studio’s lights did not damage it, the sabra is probably still edible. The sabra’s thorns have been removed and it can be handled without any risk. Digging into the depths of the wounded sabra can be delicious and safe as well as sexual. Yet, the object being operated upon is not human or animal and the entire image is very carefully composed. This is a stylized façade of injury and pain, a performance of trauma, and the fruit feels nothing. Perhaps the image is warning us that when dealing with trauma and memory, especially of symbols like the sabra, we are always in danger of anthropomorphizing and misreading clichéd posing as evidence of a deeper truth that has more to do with our own projections than whatever it is the object in the image might actually feel or might have undergone.

We might also wonder to what era the poster alludes. There is an aura of the outmoded and perhaps nostalgic in the choice of putting a prickly pear at the center of an Israeli poster. It harks back to a bygone era in which Israel and the pre-State Yishuv tried to define its image through Jaffa oranges, healthy workers on the Kibbutz, and new Israeli-born Jews tied to the land and living in harmony with its non-Jewish population. Following this image, we could ask when Israeli cinema started addressing the issue of trauma and memory. No doubt, dealing with these topics in a sophisticated and aesthetically innovative way is a characteristic of contemporary Israeli cinema beginning in the 1990s.5 But it is not entirely new. Even before the modernist experimentations of the Israeli New Sensibility cinema of the second half of the 1960s and 1970s and the more politically engaged films since the late 1970s that were willing to give more room to outsiders and outcasts, including Holocaust survivors and shell-shocked soldiers,6 trauma and complex webs of memory were not absent from Israeli screens. In fact many films did not seem to be able, or interested in, creating simple, linear, causal narratives. Already in the 1940s, some Zionist and early Israeli propaganda films featured traumatized Holocaust survivors. Their plots never quite managed to insert these survivors and the Holocaust into the official Zionist narrative, which attempted to chart a linear course from the destruction wrought by the Holocaust in Europe to redemption in the land of Israel.7

Some of the earliest feature films in Israel that deal with the recent past have convoluted temporal structures suggesting that they are not quite certain how these events should be conveyed and perhaps implying that they are still haunted by the past. Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer (Thorold Dickinson, 1955) begins at the end, with its protagonists—four heroes in the War of Independence—already dead. It cuts back and forth between a close up of each corpse and a roll call in which their names were read when they were still alive several hours earlier. The film then proceeds to multiple flashbacks of three of the four protagonists, which they recount as they prepare for their mission and travel to Hill 24 which they are ordered to take and hold. The story then returns to the results of their mission and the finding of their bodies, and concludes with aerial shots of Israel and the title “THE BEGINNING” (instead of more common “The End”). Although less complex, other Israeli historical films also begin at the end before going back in time, such as What a Gang (Zeev Havatzelet, 1963) and Clouds over Israel (Sinayah, Ivan Longyel [Ilan Eldad], 1966), suggesting that a simple linear chain of events was somehow not adequate to the stories Israeli cinema was trying to convey and that something about the past had not yet been put to rest.

The commercially successful compilation of old Israeli and pre-State newsreels accompanied by flippant narration, The True Story of Palestine (Ets ‘o Palestain, Nathan Axelrod, Joel Silberg, Uri Zohar, 1962), although mostly telling the standard official narrative of the creation of the State of Israel, does not in fact convey it as a simple linear plot. Rather, it opens with an old film featuring a musical act, which, according to the narrator shows that “already thirty years ago the Mat’at’e Theater was singing about the good old days that even then were already over.” The film goes on to briefly enumerate the many achievements of the State of Israel and show dancing in the streets during the Independence Day celebrations, when the narrator tells the dancers to stop. The film freezes and the narrator insists on starting “at the beginning.” He asks who took the People of Israel out of Egypt, as the film appears to be rewinding and reaches an image of the biblical Moses holding the Ten Commandments. “Hardly 3,000 years passed,” the narrator continues as the film appears to whiz forward, “and who told the Jews to leave their exile? That’s right! Herzl,” as the film stops on a picture of the founder of modern political Zionism. It continues with the first Zionists who arrived in Israel and with filmmaker Nathan Axelrod coming with his “Kinoapparat” and making his moving pictures. It is only now that the narrator, addressing the audience, announces that “our historical film begins.” Most of the film is a roughly linear account of the major events leading from the first Zionist settlers in Palestine, through the struggles and fight for independence against the British and Arab armies, to the successful founding of the State and the opening of its borders to the Jews who had not been allowed to enter during the Holocaust and now had a homeland. It then returns to the frozen frame of the Independence Day celebrations, the narrator says they can now resume dancing, and the movement recommences as the film concludes. Even this good-natured humorous take on official Zionist history as the Israeli film industry was experimenting with its first feature films seems to warn us not to assume that there ever were “good old days.” Already in the early 1960s it was no secret that collective memories (such as the Independence Day dancing) were in tension with history (which the narrator insists on conveying); that official narratives leave glaring gaps (the bizarre attempt to connect modern nationalism with biblical times while ignoring millennia of Diasporic Jewish identity and traumatic catastrophes); and that the films that become part of public memory were not transparent records but part of a deliberate political struggle (the historical arrival of Nathan Axelrod and his film camera are compared with Herzl and the first Zionists to come to the Land of Israel).

The role of memory and trauma in Israeli cinema in all periods is far from obvious. It is a theme that floods our screens today but has also never been absent in other ways and modes in previous decades. It traffics in secrets and repressions but does so in a public, international, and highly accessible medium. It purports to reveal unacknowledged truths but its authenticity can easily be questioned. The contents can be harsh, perhaps unbearable and shameful to those remembering, yet there also seems to be some pleasure in making the films, watching them, and scrutinizing them within academic scholarship. We asked the contributors of this book to offer new and critical views on this topic. Happily, they accepted our request and produced innovative essays that challenge prevailing tendencies in trauma and memory studies; combine them with other theoretical approaches; deal with Israeli cinema together with other, non-Israeli texts; inventively regroup and interpret Israeli films; shed light on films and videos that have received little scholarly attention; and attend to the novel aesthetic choices made in these films.

Trauma and memory studies

While each of the following chapters has pursued a different theoretical course, most of them address, and sometimes challenge, the current discourse on trauma and memory in the humanities and in film studies.8 Recent interest in trauma is related to the category of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), introduced in 1980 by the American Psychiatric Association into its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This category was created following shifts in American psychiatry and also because of social, economic, and political pressures, including opposition to the Vietnam War and the image of the war and its combatants, and feminist struggles during the 1970s.9 As Cathy Caruth notes, “this classification and its attendant official acknowledgment of a pathology has provided a category of diagnosis so powerful that it has seemed to engulf everything around it: suddenly responses not only to combat and to natural catastrophes but also to rape, child abuse, and a number of other violent occurrences have been understood in terms of PTSD.”10 Interest in trauma is also related to the renewed critical discussion of the Holocaust in the humanities including the experiences and works of second-generation survivors.11 Trauma has also become a component in some of the critical concern with the representation of oppressed groups and minorities in society ...