![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Disturbing Appetites: Fat, Fitness, and Fine Dining

Perhaps it is not surprising that 1980s horror features extreme bodies and appetites as sources of terror. While American culture encouraged the public to view spending more, owning more, and eating more as markers of personal success, it also valorized self-restraint and denial. In the same year McDonald’s launched supersized meals in 1972, for instance, Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution made publishing history with hardcover sales topping $1.1 million (Seid 4). Such conflicting messages only intensified in the following decade. Weight Watchers, aerobics, televised exercise shows, and low-calorie soft drinks competed with fast food, 7-Eleven, and all-you-can-eat buffets. Amid these contradictions, the fat body emerged as an image for what not to be. It defied cultural norms that valorized the thin body. It justified discrimination. And it was treated with disgust and disparagement.

Fat ridicule in horror comedies offers one example of this trend. In Fred Dekker’s The Monster Squad (1987), Fat Kid (Brent Chalem) blames his weight and junk-food addiction on “a glandular problem.” He even considers taking a bite of garlic pizza before using it as a weapon against Dracula. A similar character, Chubby (Mark Holton), appears in both Teen Wolf (1985) and Teen Wolf Too (1987). Like his name suggests, he gets defined entirely by his weight. Chubby’s eating habits, such as hiding food in his locker and swallowing an entire bowl of Jell-O, provide an ongoing opportunity for mockery.1 Similarly, Richard Donner’s The Goonies (1985), based on a story by Steven Spielberg that fuses action, fantasy, gangster, and horror conventions, includes Chunk (Jeff Cohen), a boy who devours Miracle Whip, Baby Ruth candy bars, pizza, Twinkies, milk shakes, and ice cream. His body serves as a source of humor among his friends who often force him to do the “Truffle Shuffle” (lifting up his shirt and jiggling his stomach). While these types of films typically attribute fatness to poor dietary choices, they downplay weight-based derision by presenting these characters as heroic members of a tightknit group. Fat Kid and Chunk, for instance, act valiantly to fight danger, and Chubby can score a basket or win a boxing match when his team needs it most. Nevertheless, fatness defines and limits these boys. It shapes the way others perceive them, and it guarantees ridicule long after the final credits roll.

Chunk (Jeff Cohen) does the “Truffle Shuffle” in Richard Donner’s The Goonies (1985). © Warner Brothers.

Despite such problematic depictions of the fat body, Fat Studies has been reluctant to examine horror. Casey McKittrick, in Hitchcock’s Appetites: The Corpulent Plots of Desire and Dread, attributes this hesitancy to the field’s traditional focus on social sciences (as opposed to the humanities), on women, and on discrimination. For scholar Niall Richardson, the problem stems from the way horror can often excuse fat-phobia, and he specifically critiques Brett Leonard’s Feed (2006) for making excessive fat “the most terrifying visual element of the text” (45). Yet as McKittrick and Richardson demonstrate, Fat Studies offers an invaluable framework for interpreting bodily extremes in horror—whether appreciating the genre’s efforts to combat fat bias or pointing out its shortcomings. In the case of the 1980s, some of the most provocative works of horror fiction, including Stephen King’s Thinner (1984), Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love (1989), Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs (1988), and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991), engage in fat activism by exploring the tension between consumption and deprivation, fat and thin.

Beginning with an overview of the exercise craze, diet foods, and weightloss programs, this chapter considers the way horror responded to these practices. Philosopher Noël Carroll acknowledges that horror “may typically only command a limited following, [ … but it can garner] mass attention when its iconography and structures are deployed in such a way that they articulate the widespread anxiety of times of stress” (214). Contemporary horror spoke to profound fears about fatness throughout the decade. From Buffalo Bill’s obsession with heavyset women in The Silence of the Lambs to Billy’s emaciated body in Thinner, these works suggest that the pursuit of thinness can be just as dangerous as the unhealthy habits responsible for significant weight gain. They situate horror in a marketplace that capitalizes on being both the problem and the solution, encouraging one to supersize meals and buy diet books. In this way, 1980s horror uses bodily extremes to interrogate the dangers of consumer culture and to challenge readers to rethink their relationship with food, dieting, and body size.

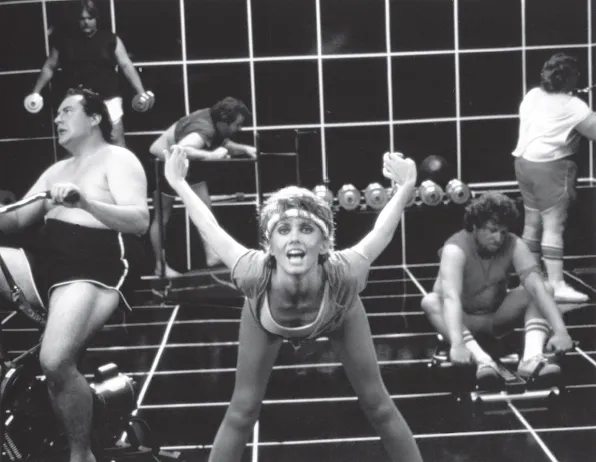

Weighing In: Fitness, Diet Culture, and Food

In 1963 British-born Olivia Newton-John made her singing debut on Australian television at the age of fifteen, and the release of her first single three years later launched an award-winning musical career that would span decades and sell over 100 million records. While she had earned three Grammys by 1974, it was her onscreen romance with John Travolta in Grease (1978) that catapulted Newton-John to stardom in the United States. Two years later she found herself alongside legendary Gene Kelly, but no amount of ballroom dancing (or roller skating!) could rescue Xanadu from critical and box-office failure. Its soundtrack, however, sold over 2 million copies with two chart-topping songs by Newton-John. When she released the title song from Physical in 1981, it reached number-one on the Billboard charts for ten weeks and remained a hit song throughout most of 1982.2 The music video, which helped secure the song’s success, features Newton-John as a beleaguered fitness instructor of fat white men. With the empathy of a drill sergeant, she marches around the gym, ratcheting up the speed of treadmills and exercise bikes much to the chagrin of her sweaty, clumsy clients. She grabs, shoves, chokes, and even straddles these men while urging them to work harder. Their milk-white bodies nearly burst out of the tiny shirts and gym shorts designed to accentuate their fatness. Large bellies—often shown in close-up—jiggle and roll. A grimace accompanies each aerobic step, and long before the end of the routine, each man falls to the floor from exhaustion. Newton-John rolls her eyes with exasperation and resigns herself to a shower. Yet when she returns in a perky tennis outfit, most of her clients have transformed into lean, well-oiled, well-shaved specimens of masculinity, flexing their muscles and wearing thongs. She inspects their biceps and flat stomachs—as if to choose her next lover—but the men begin to pair off together, holding hands and wrapping their arms around each other. It would seem that fit men prefer other fit men.3

Olivia Newton-John and her fat clients in “Physical” (1981). MCA Records/Photofest. © MCA Records

This sadistic workout and its portrayal of heavyset men are in keeping with derisive attitudes about fatness that intensified throughout the decade. Donning the type of outfit that both Jane Fonda would cultivate for her 1980s workout videos and Alex Owens (Jennifer Beals) would wear for her audition in Flashdance (1983), Newton-John implores a would-be lover to stop talking and to revert to animalistic, physical impulses. Part of the song’s refrain—about hearing the body talk—is simply a call to action. Nevertheless, the video’s setting clearly suggests that being sexually desired means the cultivation of a lean, muscular body. Its tongue-and-cheek humor reinforces this message. Most of the “jokes” come at the expense of large bodies, particularly because of the men’s vaudeville-like antics as they flounder through aerobics routines and use Nautilus equipment like rodeo cowboys on an angry bull. In the context of “Physical,” fatness needs to be controlled. It needs to be transformed into something desirable through intense effort, self-discipline, and masochistic levels of exercise. Otherwise, one will be reduced to some of the commonplace stereotypes about fat people at the time: as lazy, sloppy, greedy, stupid, and lacking self-restraint. Only by shedding pounds will these men escape this fate. Only by reclaiming the thin bodies hidden beneath the excess weight will they be able to “get physical.”

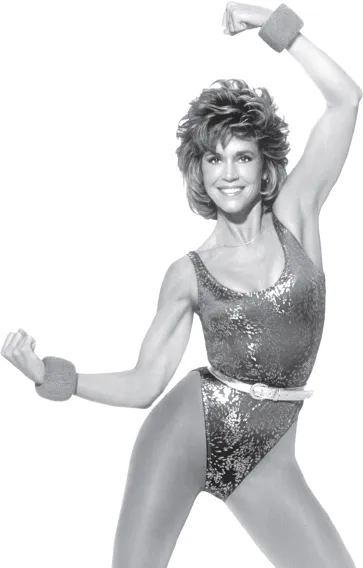

As a thirty-three-year-old pop singer with a youthful appearance, Olivia Newton-John could still write music that resonated with American teens in 1981. She may have been ten years older than Madonna, who released her first single in 1982 and her first album a year later, but Newton-John’s aerobics outfit in “Physical” played into a burgeoning trend, while downplaying the sexually explicit lyrics of the song. At the time she had no desire to release a workout video, publish a predominantly vegetarian cookbook (as she would in 2012), or produce her own wine (as she would in 2015).4 Jane Fonda, however, saw an opportunity to channel her activism through physical fitness. Her outrage over the impact of Playboy culture on women throughout the world inspired her to view fitness as a means for liberation. As she explains in Jane Fonda’s Workout Book (1981), “your goal is not to get pencil thin or to look like someone else. Your goal should be to take your body and make it as healthy, strong, flexible, and well-proportioned as you can—[ … to be] comfortable and confident about your physical self” (64). The forty-four-year-old Fonda may have been the perfect celebrity to launch a fitness movement. In addition to her own struggles with dieting, eating disorders, and drug addiction,5 her image as a wife, mother, and progressive, countercultural activist made her a trustworthy voice for women who wanted to take control of their own bodies.

For Fonda, however, aerobics was also a means for rejecting the cultural devaluation of aging. She cautioned against fats, sugars, meats, and processed foods, in part, because such foods—along with a lack of exercise—exacerbated the aging process. Next to fatness, nothing could be worse in America than getting old. In many ways, her view of aerobics as a fountain of youth inadvertently promoted some of the same attitudes she had been railing against. As Eric Oliver explains in Fat Politics: The Real Story behind America’s Obesity Epidemic, “Although women cannot reverse their age, they can affect something that is highly correlated with youth: body weight. This means that women will begin to assess themselves relative to their own thinness” (92). The more thin bodies get equated with youth, in other words, the more pressure women feel to control their weight. Scholars Joseph Maguire and Louise Mansfiend come to a similar conclusion in their analysis of 1980s aerobics: “Aerobics class reflects and reinforces the dominant desire to be thin and is an exercise practice that harnesses a great degree of oppression for the women who participate” (111). Ultimately, the sculpted female body—whether promoted through Fonda’s videotapes or the images produced by Madison Avenue—tended to fuel an unhealthy desire among women to remain thin, beautiful, and young.

Of course, Fonda did not invent aerobics nor did she produce its first video. Based on the work of exercise physiologist Dr. Kenneth Cooper in his book Aerobics (1968), both Judi Sheppard Misset and Jacki Sorensen invented the type of aerobics Fonda would catapult into a national obsession. Most experts considered exercise a valuable supplement to dieting at the time, but it was not viewed as essential for weight loss and bodily transformation until the late 1970s. According to Roberta Pollack Seid, “only 21 percent of American adults exercised regularly” in 1961, yet twenty years later, “the percentage had leapt to 60” (8). Furthermore, “between 1981 and 1985 an estimated 25 million Americans had joined the latest activity, aerobic dance classes, which proved to be primarily a female form of burning fat and building muscles” (236). These remarkable numbers were fueled, in part, by Jane Fonda’s Workout Book and her subsequent videos, including Jane Fonda’s Workout (1982), Pregnancy, Birth and Recovery (1983), Workout Challenge (1984), Prime Time Workout (1984), New Workout (1985), Low-Impact Aerobic Workout (1986), Sportsaid (1987), and Workout with Weights (1987). Elizabeth Kagan and Margaret Morse reported at the time that “Twenty-nine percent of aerobics participants in 1986 used aerobics videos, and, overall, 15 million tapes [had] been sold since the first one went on the market, 3.5 million of them by Jane Fonda” (164–65). A wide range of celebrities such as Raquel Welch, Richard Simmons, Marie Osmond, Bruce Jenner, Martina Navratilova, Lou Ferrigno, and Arnold Schwarzenegger joined Fonda in flooding the market with fitness programs. Exercising soon became a national ethos. The demand for home workout equipment grew 150 percent between 1978 and 1983. The clothing industry saw a 60 percent increase in sales of exercise outfits between 1981 and 1982, and women purchased 30.2 million leotards in 1983 (Seid 8).

Unlike any prior period in American history, the 1980s viewed the toned, fat-free body as its goal. Only through the pain of strenuous exercise could one achieve it: “You must be committed to working hard, sweating hard, and getting sore,” Fonda writes. “No sweatless quickies” (55). Failure to do so guaranteed some degree of social marginalization and ridicule. It meant the possibility of being viewed as one of the fat, uncoordinated clients in “Physical.” Aerobics and bodybuilding—alongside images in popular culture such as Newton-John’s video—sent a clear message about appearance as the measure for personal worth. The taut body, as well as the exercise regimen to achieve it, reflected admirable personal characteristics such as determination, dedication, and self-control. As Susan Bordo argues in Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, “the firm, developed body [became] a symbol of correct attitude; it [meant] that one ‘cares’ about oneself and how one appears to others, suggesting willpower, energy, control over infantile impulse, the ability to ‘shape your life’” (199). These symbolic meanings fueled a growing hostility toward fatness and buttressed a national weightloss imperative that viewed fat as a problem to be overcome. Unlike shifting attitudes toward alcohol and drug addiction, which became more widely accepted as problems of physiological dependency, fatness was a failure of will and a sign of moral weakness.

Cover for Jane Fonda’s Low-Impact Workout (1986). Karl Lorimar Video/Photofest. © Karl Lorimar Video.

At the same time, 1980s workout culture thrived alongside diet products that reinforced similar messages about the body. Twenty-one years after Weight Watchers opened for business in 1963, it had 13 million participants with nearly 500,000 people attending weekly classes, and another 825,000 people subscribing to its magazine (Seid 6; Schwartz 241). Diet soft drinks had been growing in sales since the 1960s, and after the FDA approved the artificial sweetener aspartame in 1981, they cornered 20 percent of the overall soda market by 1984. In the same year, the company that developed NutraSweet earned $585 million in revenue. Over-the-counter drugs for weight control boomed as well. Laxatives, diuretics, and vitamin and mineral supplements climbed in sales throughout the decade. “Starch blockers” earned $150 million in 1982, and the products Appedrine, Prolamine, Control, and Dexatrim became a billion-dollar industry in 1985 (Schwartz 245).

As many scholars have noted, one remarkable feature about this diet culture has been its utter failure to achieve results. Americans got heavier in the second half of the century, not thinner. In 1958 Doctor Alan Stunkard determined that most people seeking “obesity treatment” would either not lose weight or simply regain any losses, and a 1992 NIT Technology Assessment Conference on Voluntary Methods of Weight Loss and Control “affirmed Stunkard’s earlier findings that 90–95% of participants in all weight loss programs failed to attain and sustain weight loss beyond two to five years” (Lyons 77). By 1985 approximately 90 percent of Americans considered themselves overweight—a statistic that coincided with the fact that 313 diet books were in print and that 4 million people watched the Richard Simmons Show every week (Seid 3–4). Ironically, the designation of “overweight” in the early part of the decade required a BMI of 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women. Not until 1988 did the National Institutes of Health (NIH) change this standard, advising the medical community to label a BMI of 25 as “overweight” and a BMI of 30 as “obese.” With this shift, 37 million Americans suddenly became overweight.6

This recommendation, however, was not based on any scientific evidence, and the NIH’s claims that a BMI higher than 25 led to “significantly higher mortality” were not supported by the data in its own report (Oliver 22). Economic interests—particularly those of pharmaceutical corporations and scientific professionals—shaped these findings, not legitimate concerns for public health.7 Nevertheless, as this 1985 survey indicates, the NIH was merely catching up with public sentiment. Most Americans already viewed themselves as too fat, making these new BMI standards a mere confirmation of their worst fears, not a revelation. The diet industry quickly capitalized on these findings by promising a solution to the obesity problem, but it failed to do so on every possible level. It did not help most people lose or keep off weight. Instead, it encouraged a climate of perpetual dieting. It fostered intolerance and hostility by vilifying bodily differences. And it led to public health policies that cast fatness as a profound social problem responsible for skyrocketing health-care costs, a lack of patriotism, and even global warming.8

New Yorkers try to escape both the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man and their addiction to sugar in Ivan Reitman’s Ghostbusters (1984). Columbia Pictures/Photofest. © Columbia Pictures.

As suggested by this brief overview of exercise and diet practices, a profound fear of fat remained at the center of American life in the 1980s. It demanded an obsessive pursuit of the thin body and captured a fundamental contradiction in American culture: the simultaneous desire for excess and self-control. Ivan Reitman’s Ghostbusters (1984) offers a playful example of this dichotomy. The specter of fatness haunt...