![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Dan Herbert

Vocational Education and Training in Context

In most countries, post-secondary education is, at least in part, split between what may be termed ‘academic’ and ‘vocational’ pathways. Academic pathways are most often aimed at preparing students for higher, degree level, education whilst vocational pathways are aimed primarily at preparing students for employment. The status and quality of the vocational pathways vary, with some countries, for example, Germany (Deissinger, 2015), being seen as an example where the vocational and academic pathways have equal status. In others, including the UK, the vocational pathway in post-secondary education has often been viewed as an inferior choice for those not able to pursue further academic study (Unwin, 2004). In the UK, vocational pathways are disproportionately followed by students from low socio-economic backgrounds.

Whatever its perceived status, Vocational Education and Training (VET) is economically valuable and supports the skills needed in society. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identifies short- and long-term benefits from VET for individuals, employers and society. Individuals benefit in the short term from improved employment chances, enhanced earning levels and increased work satisfaction. Employers’ short-term benefits include higher productivity from a well-trained workforce and saved costs from recruiting external skilled workers. Society benefits from reduced welfare costs due to higher employment arising from improved transition from education to employment. In the longer term, those undertaking VET tend to access further training later in their careers, employers experience lower staff turnover and society gains from productivity increases and the increased tax revenues this leads to (Hoeckel, 2008).

The provision of VET and the nature of qualifications vary considerably in different countries and contexts. In some countries, such as the Netherlands (MBO, n.d.), the focus is primarily on preparing students for a particular occupation, often linked to an apprenticeship or periods of work experience. VET is delivered in specialist colleges often with a focus on, and strong links with, a particular industrial sector. In others, such as France (MNE, 2010) and the UK, VET also contains a significant proportion of academic general education, and the academic and vocational pathway curricula overlap. Where this is the case, VET may be focussed on career preparation but may also act as a route to higher education. This range of provision means that it is difficult to arrive at a single definition of VET that captures the full range. Moodie (2002, p. 260) suggests that ‘one may consider vocational education and training to be the development and application of knowledge and skills for middle-level occupations needed by society from time to time’. Whilst this definition is too general to be applied to specific instances of VET provision, it does capture the key elements. VET is a distinct set of education provision separate to general academic education and provided in ways that support the development of skills, knowledge and behaviours for the labour market.

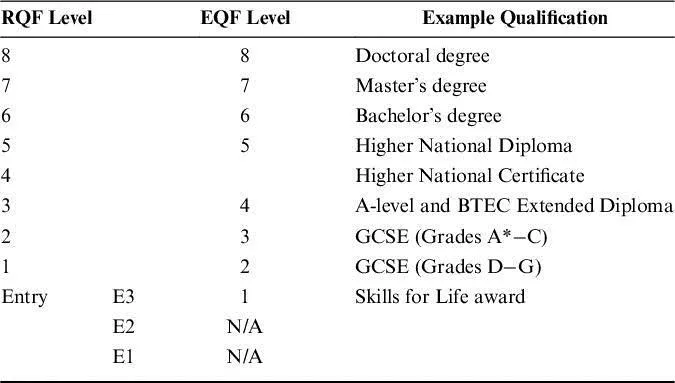

In almost all countries, a qualifications framework is used to rank VET by level and, in Europe, the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) allows for international comparisons. The EQF allows national qualifications to be compared against set criteria and for VET qualifications to be benchmarked for level against general academic qualifications. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the current framework is called the Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF). The RQF ranks programmes by ‘difficulty’ and the time taken to study for them. The UK BTEC Extended Diploma qualifications that are the focus of this work are level 3 on the UK national RQF, which equates to level 4 of the EQF. This represents the highest level of qualification below the Bachelor’s degree level and the academic A-level qualification is also ranked at level 3 of the RQF.

The Development of Vocational Education in England

The roots of the current English system of VET lie in the late nineteenth century when, in 1867, the Schools’ Enquiry Commission identified that a relative lack of technical education compared to other European countries was putting the country at a disadvantage. This related in particular to the technical skills needed for developing manufacturing businesses. In 1875, the City and Guilds of the London Institute for the Advancement of Technical Education was founded, offering a wide variety of courses and examinations in a range of crafts. The development of VET progressed in a haphazard manner with responsibility for VET being seen to lie with employers rather than the state taking responsibility as happened in countries such as Germany (Foreman-Peck, 2004). This situation and the lack of formal structure continued through to the early 1970s.

The origins of the BTEC qualification stem from the formation in 1973 and 1974 of the Technical and Business Education Councils (TEC and BEC). These bodies were formed to provide an improved structure for, and regulation of, VET. The TEC and BEC were merged in 1983 to form BTEC. However, the position of the Council was not secure and in 1994 the development of National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) as a new VET qualification seemed to threaten other VET qualification frameworks. The NVQ framework was withdrawn in 2015 and since that time BTEC has become a core qualification for 16–19 education.

The BTEC National Extended Diploma is the most significant core level 3 RQF qualification that provides students with a vocational pathway that may lead to employment or university study. It is this qualification which has been the focus of the research underpinning this book. The BTEC Extended Diploma is now recognised as a popular entry route to university, and as can be seen in Table 1, it has equivalence with A-level. In the UK, qualifications acceptable for university entry are awarded tariff points by UCAS. Under this scheme, students achieving the highest D*D*D* grading in a BTEC Extended Diploma achieve the same tariff point score (168) as those achieving 3 A-levels at A*, the highest grade for an A-level (UCAS, 2018). From 2016 onwards, revised BTEC Nationals in 28 subject areas have been introduced, updating and improving the existing qualification. The revised qualification has an increased emphasis on preparing students for further study with improvements to the content and structure of the award as well as revised assessment processes.

Table 1. The Development of VET in the UK.

Since the 1990s, there has been common political agreement that the status and quality of VET need to be improved if it is to provide the desired outcomes for individuals, businesses and society. A series of reviews and reports have addressed this issue but the VET provision in the UK is still confused and lacking in structure. In 2016/2017 students were enrolled on around 4,700 level 2 and level 3 VET qualifications. The recent political focus on VET has led to a number of reports that investigated the provision of VET. Of these, the Wolf Report (2011) was the most influential and identified significant areas of weakness in VET provision. This report was the most wide-ranging review of VET in England and made recommendations across a range of policy, regulatory and quality issues. Of relevance to the BTEC qualification is the recommendation concerning the nature of qualifications.

16–19 year old students pursuing full time courses of study should not follow a programme which is entirely ‘occupational’, or based solely on courses which directly reflect, and do not go beyond, the content of National Occupational Standards. Their programmes should also include at least one qualification of substantial size (in terms of teaching time) which offers clear potential for progression either in education or into skilled employment.

(Wolf, 2011, p. 14)

The clear recommendation is that VET qualifications should not be purely focussed on preparation for a specific occupational role but should also contain substantial subject content that allows for progression in education, presumably to degree level study, if a student does not move directly into employment.

Perhaps the most significant development in English VET flowing from the recommendations of the Wolf Report is the development of T levels. The first of these new qualifications will launch in 2020 in three subject areas with a further seven areas launching in 2021. T levels will offer an alternative VET pathway for students not wishing to pursue the A-level-based general education pathway in post-secondary education. The objective of T levels is to improve the quality of VET by providing a qualification with general academic content ensuring minimum standards in Mathematics and English, core skills and theory related to an industry sector, specialist skills and knowledge for a specific career and a period of work experience.

In May 2019, a review of Post-18 Education and Funding (the Augar Review) was published. It formed the most comprehensive review of all post-18 education, both vocational and academic, since 2011. The review placed a strong emphasis on the need for improved technical and vocational education. In particular it identified the need for flexibility in entry points, for example, by allowing students with a RQF level 4 qualification to join a degree programme to up-skill or re-skill themselves perhaps after a period away from formal education. The report envisages a regime whereby individuals can access funding based on modules studied rather than whole programmes. Whilst the review focussed on the changes to funding regimes that would be needed to facilitate this flexibility, the proposal poses a pedagogic challenge. How will universities offering more flexible entry routes ensure that students, perhaps predominantly with vocational qualifications, are able to transition effectively back into formal education? The evidence presented in this book regarding the challenges faced by students and the necessary responses by education providers may help inform the design of educational programmes that enable effective transition into education at different stages.

The Augar Review also comments on the structural issues relating to the increasing numbers of students entering degree level education with BTEC qualifications. In particular, it notes the marked increase in students achieving the highest grades in their BTEC studies and the apparent generous treatment of BTEC when allocating UCAS tariff points on which universities make offers to students. The review also comments on the difficulties faced by Further Education Colleges (FEC) which are the main providers of BTEC and other vocational education. The report notes that FECs are subject to a complex regulatory regime, low levels of per-student funding and that staff are paid at levels below equivalent staff in schools and universities. The report’s recommendations for FECs relating to funding, investment and regulation present an opportunity for improvements in VET that allow students to be better prepared for further study if they choose to take this route.

The Transforming Transitions Project

The project that forms the basis of this book arose from the need to address the issues that arise when students with BTEC qualifications progress to higher education. The BTEC is a specialist work-related qualification (Pearson, 2018) and whilst it may also provide a route to further study, this is not the sole or primary aim. However, the popularity of the qualification has resulted in increasing numbers of students studying them and also progressing to further study. In 2018, approximately 10% of all university entrants in the UK had studied only for a BTEC qualification. However, this headline figure hides the imbalanced nature of the progression from BTEC to degree level study. BTEC entrants tend to study for a narrow range of degree subjects (Business, Sport and Exercise Science, Health-related professions) at lower entry tariff universities.

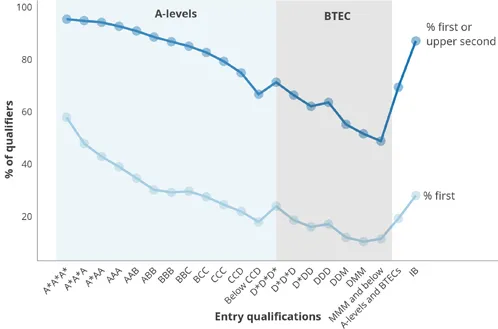

The particular issue which provided the impetus for the project was the concern that students with vocational qualifications, such as the BTEC, were not accessing the most selective universities and were not progressing through university in the same way that students with A-levels do. Indeed, the data suggest that the outcomes for students entering University with BTEC qualifications are worrying. BTEC qualified students are less likely to achieve a ‘good degree’, that is, one awarded at first or upper second class honours using the UK classification system, when compared with A-level students. Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) data (HEFCE, 2018) show that even those with the best BTEC results on university entry tend to achieve degree outcomes which are in line with those with mid to low A-level results. Figure 1 shows these relationships and that those with the highest ranked BTEC results (D*D*D*) achieve first and upper second class honours awards at a level that compares with those achieving relatively low grade (CCC) A-level equivalents. The pattern is similar for the award of first class honours.

Figure 1. Degree Classification by Entry Qualification for 2016–2017 Graduates.

Moreover, aside from eventual degree outcomes, BTEC qualified students are also less likely to complete their studies. Figures for withdrawal from university after one year of study show that BTEC qualified students have higher dropout rates. The evidence shows that BTEC students are more likely to drop out of university when compared with those on a traditional academic pathway, even when accounting for prior attainment (Hayward & Hoelscher, 2011). This emerging pattern of differential outcomes comes in the face of evidence which suggests that young people with more access to the types of programmes and activities (e.g. work experience, career talks, workplace visits and so on) are equipped with better networks and knowledge of labour market and make more informed decisions leading to a more successful transition to adult employment (OECD, 2010; Symonds, Schwartz, & Ferguson, 2011).

The transition to university is an important educational step for students yet the impact of transition experience on final outcomes is poorly understood. There is evidence that personal and academic issues and student expectations that are not addressed during the transition can lead to feelings of estrangement that may contribute to the marked differential outcomes on graduation (Jones, 2018). The Transforming Transitions project was inspired by the desire to better understand the transition journey of BTEC students and to discover whether improving this journey could lead to a closing of the outcome gaps. The project was funded by the HEFCE (now Office for Students) Catalyst programme, Addressing Barriers to Student Success (HEFCE, 2017). This programme was a suite of projects across the country designed to improve the outcomes of students from all backgrounds, and was a response to the earlier work, commissioned by HEFCE, which had highlighted the problem of differential outcomes for students from different groups (Mountford-Zimdars et al., 2015). This had focused on the poorer outcomes for black and minority ethnic (BME) students, students from low socio-economic backgrounds, disabled students and mature students. Our particular interest in vocational education, particularly the BTEC, stemmed from the research which indicated that these students are more likely to be from one or more of these groups, and that the relationship between vocational education, social disadvantage and degree outcomes had not been fully explored.

A key feature...