Geography

Hydrosphere

The hydrosphere refers to the total amount of water on Earth, including water in the oceans, rivers, lakes, groundwater, and in the atmosphere. It plays a crucial role in shaping the Earth's surface and influencing weather patterns. The hydrosphere is an essential component of the Earth's interconnected systems, impacting both the environment and human societies.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Hydrosphere"

- eBook - PDF

- Amrita Pandey(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

In recent times, there are several human activities that are impacting the Hydrosphere and hampering the processes that support the life systems on the Planet Earth. 4.1. INTRODUCTION Hydrosphere is that part of the ecosystem of Earth which consists of the parts of the earth ecosystem that are composed of water in its liquid, gaseous or vapor and solid or ice forms. The Hydrosphere comprises of the major water bodies like the oceans and seas; solid mass of water such as ice sheets, sea ice and glaciers; sources of freshwater such as lakes, rivers and streams; its atmospheric humid content and ice crystals; and its zones of permafrost. The Hydrosphere consists of both the saltwater and freshwater systems, and it also comprises of the moisture that is usually found in the soil, in the form of soil water and inside rocks, which is usually known as groundwater. Water is very crucial for the production and survival of any kind of life form on the planet earth. According to some systems and experts, the Hydrosphere is usually classified into the fluid water systems and the cryosphere, which is commonly called as the ice systems. The Hydrosphere is formed by all the parts and zones of water on the planet Earth. It comprises of water that is present on the surface, under the surface or on the sub-surface and as the water vapors in the atmosphere. Many experts have denoted the spheres of Hydrosphere and the atmosphere as the fluid spheres. Both of these spheres contain the entire content of the liquid and the gas constituents of the earth. To understand the Hydrosphere, one must have an idea of the entire water in the oceans and seas, along with the frozen water and ice, which is known as cryosphere. Also, an individual must have an idea of all the freshwater bodies such as lagoons, bays, rivers and ponds, along with the water in the water table that is present underneath the surface of the earth. - eBook - ePub

Environmental Change

The Evolving Ecosphere

- Richard Huggett(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

5Hydrosphere

DIRTY LIQUID: WATER

Planet ocean

The Hydrosphere is all the Earth’s waters. It includes liquid water, water vapour, ice and snow. Water in the oceans, in rivers, in lakes and ponds, in ice sheets, glaciers, and snow fields, in the saturated and unsaturated zones below ground, and in the air above ground is all part of the Hydrosphere. Some people set the ambits of the Hydrosphere to exclude the waters of the atmosphere.The Hydrosphere presently holds about 1,384,120,000 km3 of water in various states (Table 5.1 ). By far the greatest portion of this volume is stored in the oceans. A mere 2.6 per cent (36,020,000 km3) of the Hydrosphere is fresh water. Of this, 77.23 per cent is frozen in ice caps, icebergs, and glaciers. Groundwater down to 4 km accounts for 22.21 per cent, leaving a tiny fraction stored in the soil, lakes, rivers, the biosphere, and the atmosphere.Water is the chief component of the Hydrosphere. Concentrations of constituents dissolved in water vary in different parts of the Hydrosphere (Table 5.2 ). Sodium and chlorine are the main constituents of sea water. The acidity of waters in the Hydrosphere is highly variable. The most acid natural waters on Earth occur in volcanic crater lakes. These may have a pH less than 0 (e.g. Brantley et al. 1993). Water free of carbon dioxide in contact with ultramafic rocks may have a pH of 12. Soils in desert basins and rich in sodium carbonate and sodium borate may be equally alkaline. In most environments, 9 is the upper limit of pH.Circulating water

Water, even in its solid state, seldom stays still for long. Meteoric water circulates through the Hydrosphere, atmosphere, biosphere, pedosphere, and upper parts of the crust. This, the water cycle, involves evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and runoff. It is not a closed system. Deep-seated, juvenile water associated with magma production may issue into the meteoric zone; while meteoric water held in hydrous minerals and pore spaces in sediments (connate water) may be removed from the meteoric cycle at subduction sites. - eBook - ePub

Understanding Global Climate Change

Modelling the Climatic System and Human Impacts

- Arthur P Cracknell, Costas A Varotsos(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

However, more recently, Gavin Menzies, a retired submarine lieutenant-commander from the (British) Royal Navy, has argued that Zheng He’s fleets travelled much more widely, crossing the Atlantic Ocean reaching America decades before Columbus, as well as reaching Australia and New Zealand (Menzies 2004, Menzies and Hudson 2013). Although Menzies’ work has been challenged, we find it convincing and we conclude that to achieve all that the Admiral and his fleet must have had a good knowledge of the oceans, winds, and currents and they were able to navigate and to establish their latitude from observations of the stars. Hence, our choice of him to introduce this chapter. As an aside we mention that if Menzies’ two books that we have just cited are controversial, his other book (Menzies 2008) is even more so. In that, he argues that the Renaissance was not sparked as a result of the rediscovery of Greek philosophy but by the visit of Zheng He’s fleet to Italy in 1434. In that year, the story goes, the Chinese delegation met the influential pope Eugenius IV and presented him “with a diverse wealth of Chinese learning: art, geography (including world maps which were passed on to Columbus and Magellan), astronomy, mathematics, printing, architecture, civil engineering, military weapons and more…”. The tragedy of the story is that when the ships that survived finally returned to China there had been a regime change and the ships were destroyed and the story of their voyages was largely suppressed.Today by the term Hydrosphere of the planet, we mean the total mass of water found on, under, and above its surface. A planet’s Hydrosphere can be liquid, vapour, or ice. In the case of the Earth, the liquid water exists on the surface in the form of oceans, lakes, and rivers. It also exists below ground – as groundwater, in wells and aquifers. Water vapour is most visible as clouds and fog (Figure 3.2 ). The frozen part of Earth’s Hydrosphere, i.e. cryosphere (see Chapter 4 ), is made of ice: glaciers, ice caps, and icebergs. Thus, the Earth’s Hydrosphere consists of water in liquid and frozen forms, in groundwater (the water present beneath Earth’s surface in soil pore spaces – contains the liquid and gas phases of soil and in the fractures of rock formations – the separation of soil into two or more pieces under the action of stress), oceans, lakes, and streams (a body of water with surface water flowing within the bed and banks of a channel).Figure 3.2 The components of the Earth’s Hydrosphere. (Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/Hydrosphere - eBook - ePub

- Barron's Educational Series, Edward J. Denecke(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Barrons Educational Services(Publisher)

Chapter 4 The Hydrosphere Earth is often called “The Water Planet” because water covers about 70 percent of its surface. All of the water blanketing Earth’s surface is called the Hydrosphere. The Hydrosphere includes all of Earth’s oceans, lakes, streams, underground water, and ice. A tiny fraction exists in the atmosphere as water vapor. Although the Hydrosphere is made up of water, it is not all plain liquid water. About 97 percent of the Hydrosphere is seawater and 3 percent is freshwater. Of the 3 percent freshwater, 2 percent is frozen or unavailable in some other way. That doesn’t leave much water for the almost 8 billion people on the planet to use. How the Hydrosphere Formed The gases released from Earth and carried in by comets that formed our current atmosphere were rich in water. (A typical comet contains about 10 15 kilograms of water—enough water to entirely fill the Great Lakes!) Because Earth was very hot, the water in Earth’s newly developed atmosphere was water vapor. Then, as Earth cooled, the water vapor in the atmosphere condensed and fell as torrential rains. At first, Earth’s surface was still so hot that the water quickly vaporized and returned to the atmosphere. But as Earth cooled further, the water remained on its surface longer and longer as a liquid. Eventually, Earth’s oceans and lakes filled with water that only returned to the atmosphere by evaporation due to the Sun, as it does today. When the atmosphere had cooled enough for some of the water vapor in the atmosphere to condense as snow or ice crystals and fall to Earth’s surface, glaciers and ice caps formed - eBook - PDF

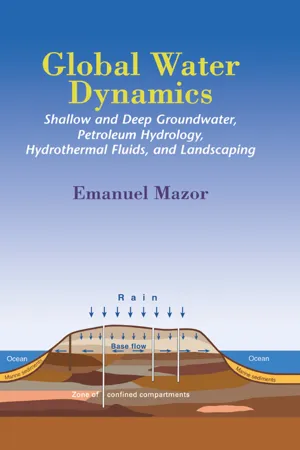

Global Water Dynamics

Shallow and Deep Groundwater, Petroleum Hydrology, Hydrothermal Fluids, and Landscaping

- Emanuel Mazor(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

PART I THE GEOHYDRODERM AND ITS MAJOR GROUNDWATER- CONTAINING GEOSYSTEMS The geohydroderm is the water-containing skin of Planet Earth 1 WATER PROPELLED GEOLOGICAL PROCESSES AND SHAPED THE LANDSCAPES OF OUR PLANET The study of the domain of water touches its distribution in the three dimensions of space and along the time dimension that provides insight into its dynamic processes. Water, in one form or another, is found all over our planet and is encountered at depths of thousands of meters within the rocky crust. Water has been around since the early days of Earth, it has a history of around 4 billion years. As liquid water in large amounts is absolutely unique to Earth, so are the outcomes and products of the water-involved geological processes. If Earth is to us a friendly home, it is thanks to all that water has created. 1.1 Water—Earth’s Sculptor The surfaces of two of our neighbors in the solar system, Mercury and Mars, are well exposed, and so is the face of our moon. On these planetary bodies we see the little- changed primordial landscape of meteoritic impact craters of all sizes, disclosing the last stages of accretion (Figs. 1.1, 1.3, and 1.4). In strong contrast, Earth has lost that primordial landscape due to continuous dynamic processes that go on to this day. Venus is covered by an atmosphere a hundred times denser than ours (Fig. 1.2) and is rich in CO 2 . The surface temperature is around 400°C, so it is no place for water. Water had a dominant role in the transformation of Earth’s landscape, playing the part of the terrestrial sculptor, propelled by two giant sources of energy: (1) the internal energy active in pushing the crustal plates and building of mountains and (2) the sun that pumps the water from the oceans Fig. 1.1 A typical landscape of Mercury, disclosing uncountable impact craters. The length of the picture is around 1000 km. (Courtesy of NASA.) The geohydroderm 3 - eBook - PDF

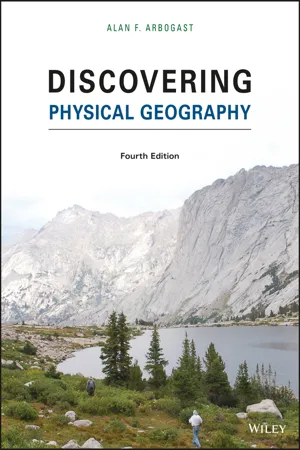

- Alan F. Arbogast(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

2. Lithosphere—The lithosphere is the solid part of Earth, including soil and minerals. A good example of a natural system in this sphere is the way in which water, minerals, and organic matter flow in the outermost layer of the Earth to form soil. This sphere provides the habitat and nutrients for many life-forms. 3. Hydrosphere—The Hydrosphere is the part of Earth where water, in all its forms (solid ice, liquid water, and gaseous water vapor), flows and is stored. This sphere is absolutely critical to life and is one with which humans regularly interact—for example, through irrigation and navigation. 4. Biosphere—The biosphere is the living portion of Earth and includes all the plants and animals (including humans) on the planet. Various components of this sphere regularly flow from one place to another, both on a seasonal basis and through human intervention. Humans interact with this sphere in a wide variety of ways, with agriculture being an obvious example. These four spheres overlap to form the natural environment that makes Earth a unique place within our solar system. Physical geography examines the spatial variation within these spheres, how natural systems work within them, the observ- able outcomes in each, and the manner in which components flow from one sphere to another. Physical geography can be a descriptive discipline that simply characterizes the nature of the Earth’s spheres in specific regions. A simple example of such a descriptive focus would be to acknowledge that the western part of the United States is mountainous, whereas the central part of the country consists mostly of relatively level plains. Physical geography is also a science because research is conducted within the framework of the scientific method, which is the systematic pursuit of knowledge through the recognition of a problem, Atmosphere The gaseous shell that surrounds Earth. Lithosphere A layer of solid, brittle rock that comprises the outer 70 km (44 mi) of Earth. - eBook - PDF

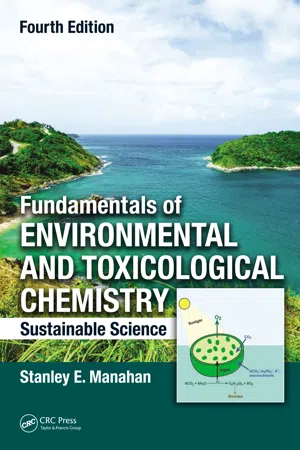

Fundamentals of Environmental and Toxicological Chemistry

Sustainable Science, Fourth Edition

- Stanley E. Manahan(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

44 Fundamentals of Environmental and Toxicological Chemistry 3.2 Hydrosphere The Hydrosphere is composed of water, chemical formula H 2 O. Water participates in one of the great natural cycles of matter, the hydrologic cycle , which is illustrated in Figure 3.2. 2 Basically, the hydrologic cycle is powered by solar energy that evaporates water as atmospheric water vapor from the oceans and bodies of freshwater from where it may be carried by wind currents through the atmosphere to fall as rain, snow, or some other forms of precipitation in areas far from the source. In addition to carrying water, the hydrologic cycle conveys the energy absorbed as latent heat when water is evaporated by solar energy and the energy released as heat when the water condenses to form precipitation. There is a strong connection between the Hydrosphere, where water is found, and the geosphere , or land: human activities affect both. For example, the disturbance of land by the conversion of grasslands or forests to agricultural land or the intensification of agricultural production may reduce vegetation cover, decreasing transpiration (loss of water vapor by plants) and affecting the micro-climate. The result is increased rain runoff, erosion, and accumulation of silt in bodies of water. - eBook - PDF

Environmental Science and Technology

A Sustainable Approach to Green Science and Technology, Second Edition

- Stanley E. Manahan(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

About 97.5% of the water in the Hydrosphere is contained in the oceans leaving only 2.5% as freshwater. Furthermore, about 1.7% is contained in the oceans leaving only 2.5% as freshwater. Furthermore, about 1.7% of Earth’s total water is held immobilized in ice caps in polar regions and in Green-of Earth’s total water is held immobilized in ice caps in polar regions and in Green-land. This leaves only 0.77% of Earth’s water — commonly designated as freshwa-land. This leaves only 0.77% of Earth’s water — commonly designated as freshwa-ter — which is regarded as potentially accessible for human use. ter — which is regarded as potentially accessible for human use. As shown in Figure 2.2, freshwater occurs in several places. Surface water is As shown in Figure 2.2, freshwater occurs in several places. Surface water is found on land in natural lakes, rivers, impoundments or reservoirs produced by found on land in natural lakes, rivers, impoundments or reservoirs produced by damming rivers, and underground as groundwater. Water occurs on and beneath damming rivers, and underground as groundwater. Water occurs on and beneath the surface of the geosphere. Groundwater is an especially important resource and the surface of the geosphere. Groundwater is an especially important resource and one susceptible to contamination by human activities. Through erosion processes, one susceptible to contamination by human activities. Through erosion processes, moving water shapes the geosphere and produces sediments that eventually become moving water shapes the geosphere and produces sediments that eventually become sedimentary deposits, such as vast deposits of limestone. Water is essential to all sedimentary deposits, such as vast deposits of limestone. Water is essential to all Atmosphere Hydrosphere Biosphere E x c h a n g e M a t e r i a l s Geosphere Anthrosphere Figure 2.1. There are five major spheres of the environment. Strong interactions, especially Figure 2.1. - eBook - PDF

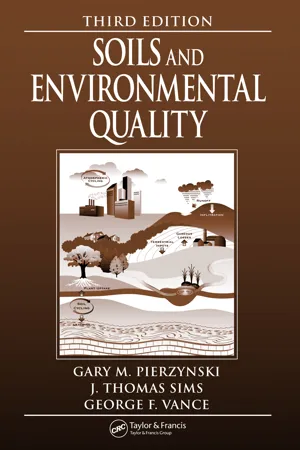

- Gary M. Pierzynski, George F. Vance, Thomas J. Sims(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Environmental quality is also important in order for humans to manage natural resources sustainably, including those essential for human, animal, and other organism survival (Chiras, 2001). The part of the planet that supports living organisms is described as the biosphere. Thus, the biosphere comprises all life-forms and their general surroundings, which include most Hydrosphere and soil ecosystems (see Chapter 3 for more details of the soil environment). Our atmosphere is primarily composed of nonliving substances and is therefore not considered part of the biosphere. However, the atmosphere, as well as most surficial environments, influences the ecology of nearly all terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Biosphere impacts, both positive and negative, are often the result of lifestyles that rely on natural resource utilization that, in turn, can affect the quality of our atmosphere and Hydrosphere. This chapter reviews the basic characteristics of both the atmo-sphere and the Hydrosphere, and examines how these two spheres are important for human subsis-tence as well as their relationship with environmental quality. 2.2 ATMOSPHERE We live in a time when concern for air quality is growing due to increasing amounts of pollutants that are added to the atmosphere daily. Our current atmosphere provides us with protection against harmful solar and cosmic radiation, moderates surface temperatures, and is a major component of the hydrologic cycle. The atmosphere also plays an important role in nutrient and contaminant transport processes. The study of the atmosphere and its phenomena is called meteorology and involves interactions between the atmosphere and the Earth’s land and ocean surfaces, as well as various influences on living systems (Aguado and Burt, 2004; Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2004). - eBook - PDF

Hydrology and Hydroclimatology

Principles and Applications

- M. Karamouz, S. Nazif, M. Falahi(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The cell has therefore come to be regarded as the simplest independent structure that pos-sesses all of the necessary properties of life. In attempting to answer these questions, therefore, it is appropriate to model the biosphere in terms of the structural and functional organization of the liv-ing cell. Therefore, the molecular basis is considered for cellular activity investigation. Fortunately, cells contain relatively few types of molecules and, although these include the most complex molec-ular structures known, many are universal in their occurrence in the biosphere. 2.8 THE Hydrosphere “Water sphere” is another name for the Hydrosphere. It includes all the Earth’s water found in the lakes, soil, groundwater, streams, and air. Hydrosphere water is distributed among several different 31 Hydroclimatic Systems stores found in the other spheres. Water is held in lakes, oceans, and streams at the Earth’s surface. Water is found in vapor, solid, and liquid states in the atmosphere. By plant transpiration, the bio-sphere serves as an interface between the spheres, enabling water to move between the lithosphere, Hydrosphere, and atmosphere as is accomplished. The hydrologic cycle traces the movement of energy and water between these spheres and stores. The Hydrosphere is always in motion like the atmosphere. The motion of streams and rivers can be seen, while the water motion within ponds and lakes is less obvious. These motions are in the current form that moves the warm waters in the tropics toward the poles and colder water from the Polar Regions toward the tropics. At great depths in the ocean (up to about 4 km), these currents exist on the ocean surface. The ocean characteristics that affect its motion are its salinity and temperature. Warm water is lighter and therefore tends to move up toward the surface, while colder water is heavier or dense and therefore tends to sink toward the bottom. - eBook - PDF

Physical Geography

Great Systems and Global Environments

- William M. Marsh, Martin M. Kaufman(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Our task in colleges and universities, then, is learning about the larger world through the windows provided by science and there is no better vehicle for approaching this challenge than physical geography. 1.2 The Great Systems of Physical Geography Before you lies Earth, the Eden planet of the Solar System (Figure 1.2). Wonderfully diverse and constantly changing, it is a geographer’s paradise. As the photograph in Figure 1.2 suggests, it is a superb place to study the patterns, processes, and prod- ucts of nature. Here we have all that the other planets possess plus a lot more, most notably vast and mobile systems of life and water, which we call the biosphere and Hydrosphere, wrapped in an envelope of gases, called the atmosphere, and set upon a stage of rock and soil, called the lithosphere. Yet, as impressive as the Hydrosphere, biosphere, atmosphere, and lithosphere are individually, Earth’s true geographic character is found by discovering their interplay, for all are intricately intertwined in great flowing systems. Giant freeway complexes are glaring illustrations of our disconnect with the land. Thoreau’s Walden Pond where he spent time contemplating and writing about nature and life. Connecting with the land in a modern world, part of being a responsible citizen of Earth. 3 The Nature of Geographic Systems In their simplest form, Earth’s systems are defined by cycles of matter and energy. Predictably, they operate at different scales and rates. Some, such as prevailing wind systems, operate almost con- tinuously over the whole planet; others, such as weather systems, begin, expand, and contract with the seasons. Still others, such as ocean currents, flow with graceful uniformity, whereas beneath the sea molten rock in volcanoes moves with unpredictable irregularity. But they are all capable of rendering change in the Earth’s surface, some slowly and gradually, some suddenly and violently. - eBook - PDF

- Larry W. Mays(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

This ozone absorbs ultraviolet radiation, playing an essential role in the stratosphere’s radiation balance, and, at the same time, it filters out this potentially damaging form of radiation. The Hydrosphere comprises all liquid surface water and subterranean water, both freshwater, includ- ing rivers, lakes, and aquifers, and saline water of the oceans and seas. The cryosphere, which includes the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctia, continental glaciers and snow fields, sea ice, and permafrost, derives its importance to the climate system from its reflectivity (albedo) for solar radiation, its low thermal conductivity, and its large thermal inertia. The cryosphere has a critical role in driving the deep-water circulation. Ice sheets store a large volume of water so that variations in their volume are a potential source of sea-level variations. Marine and terrestrial biospheres have major impacts on the atmosphere’s composition through biota, influencing the uptake and release of greenhouse gases, and through the photosynthetic process, in which both marine and terrestrial plants (especially forests) store significant amounts of carbon from carbon dioxide. Interaction processes (physical, chemical, and biological) occur among the various components of the climate system on a wide range of space and time scales. This makes the climate system, as shown in Figure 1.2.1, extremely complex. The mean energy balance for the earth is illustrated in Figure 1.2.2, which shows on the left- hand side what happens with the incoming solar radiation and on the right-hand side how the atmosphere emits the outgoing infrared radiation. A stable climate must have a balance between the incoming radiation and the outgoing radiation emitted by the climate system. On average the climate system must radiate 235 W/m 2 back into space.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.