Geography

Population Control

Population control refers to the measures and policies implemented to regulate the size, distribution, and growth of a population. These measures can include family planning, birth control, immigration restrictions, and incentives for smaller families. The goal of population control is often to manage resources, reduce environmental impact, and improve quality of life.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

8 Key excerpts on "Population Control"

- eBook - PDF

- R. Knowles, J. Wareing(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Made Simple(Publisher)

PART TWO : POPULATION GEOGRAPHY CHAPTER FIVE POPULATION DISTRIBUTION Until quite recently the systematic study of population had been largely neglected by geographers, in contrast with other fields of human geography such as agriculture, industry and settlement which have a long-established tradition of systematic analysis. However, in recent years there has been a growing awareness of the importance of population studies within the broad framework of human geography. Population geography has rapidly advanced from a peripheral position within the discipline to the stage where it has been claimed that 'numbers, densities and qualities of the population provide an essential background for all geography. Population is the point of reference from which all the other elements are observed and from which they all, singly and collectively, derive significance and meaning. It is population which furnishes the focus.* (G. T. Trewartha) Population geography is concerned with the study of demographic processes and their consequences in an environmental context. It may thus be distin-guished from demography by its emphasis on the spatial variations in the growth, movement and composition of populations, and its concern with the social and economic implications of these variations. The development of the subject has been severely limited by a lack of demographic data for many parts of the world, but, like other branches of geography, it is concerned with description, analysis and explanation, although a large part of the work to date has been concerned with population mapping and descriptive studies, simply in order to establish the data base which must precede analysis. Sources of Population Data One of the most difficult problems facing the population geographer is the varied quality of population data available for different countries and regions of the world. - eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Population Geographies

Lives Across Space

- Holly R. Barcus, Keith Halfacree(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

There is a clear prima facie case for the discipline of Demography : “the scientific study of the size, composition, and distribution of human populations and their changes resulting from fertility, mortality, and migration” (Poston and Bouvier 2010: 3). Births, deaths and human migrations between locations across the globe certainly require measurement, presentation and discussion, and future trends predicted. But whilst Demography also involves itself with the causes of the patterns, trends and magnitudes it identifies—“the factors that affect these components” (Poston and Bouvier 2010: 3)—a more dedicated emphasis on their contextualized spatial expression has become the focus of Population Geography. 1.2.2 … across real places Population Geography can be defined initially as the study of “the geographical organization of population and how and why this matters to society” (Bailey 2005: 1). An immediate illustration of how such a spatial lens is both significant and important comes, once again, via some simple demographic facts about the state of the world today (developed more fully in Chapter 3). Consider infant mortality rates (10.3.1) in a small selection of countries in Asia and Europe, shown in Table 1.1. First, even across these ten countries there is a considerable range of values. This is true even within the same continent, such as the contrast between Romania and Norway in Europe. Second, although there is a general trend towards declining infant mortality, countries such as Mongolia and India retain extremely high rates. Furthermore, many countries affected by civil strife, such as Afghanistan, Congo or Iraq, are understandably unable to provide data. Thus, Table 1.1 is biased in favor of countries experiencing relative political stability - eBook - PDF

- Rodolfo B. Valdenarro(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

Population Geographies 6 CONTENTS 6.1. Introduction .................................................................................... 116 6.2. Development of Population Geography .......................................... 118 6.3. Different Variations of Population Geography ................................. 122 6.4. The Importance of Density And Composition .................................. 124 6.5. Recent Developments In Population Geography ............................. 126 6.6. Scope of Population Geography ...................................................... 128 6.7. Important Aspects of Population Geography ................................... 129 6.8. Contemporary Population Geography ............................................. 132 Applied Human Geography 116 Population geographies have explained the concepts that had led to the improper population division all over the world. The field of Population Geography primarily lays its focus on the researches and studies of the allocation, dispersal and density of the population in any specific area all over the world. In addition to the allocation and density of the people all over the world, the discipline of population geography aims on observing the factors that affect the variations in that have been observed in the size of the population all over the world, fluctuations and attributes such as the structures, human activity, human migration and a number of activities that have been registered in the modern times. Population geography studies the aspects of the geography that has been linked with the human beings. Population geography helps the experts in understanding how the geography has changed with the sudden increase on the population all over the world and how these changes will return back to the human beings. - eBook - ePub

- Diana Coole(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Polity(Publisher)

1Should Population be Controlled?Given the impact of population change, is it in societies’ interests to control it? This chapter concentrates on the broader question of demographic ends. Demographic ends, or goals, concern policies that address a population’s growth rate, size and density. Economists, demographers and environmentalists are the principal players in this ‘numbers game’, in which natural resources, economic development/ growth and technological capabilities are especially salient elements. Normative judgements about the quality of life (the wider existential purpose served by managing numbers) are important, too, albeit often dismissed on the grounds that they are difficult to measure or quantify.Because Population Control is usually associated with (‘neo-Malthusian’) efforts to limit fertility in order to reduce growth rates, the chapter mainly focuses on consequentialist arguments for anti-natalist initiatives. It is important to bear in mind, however, that even among advocates of population policies there are disagreements about their direction: that is, whether the aim should be fewer or more people, and thus whether national governments should pursue anti- or pro-natalist policies. This partly reflects the context-sensitive nature of changing demographic impacts, which vary as economic and environmental conditions alter. But it also expresses deeper disagreements about sustained versus limited growth, competing models of wealth creation and development, disputes over how best to achieve environmental sustainability and intergenerational justice, and conflicts over anthropocentric versus biocentric ontologies.Contrary to some popular misconceptions, Population Control does not mean culling superfluous people. The aim is to reduce current birth rates in order that smaller future generations might live better. This was essentially Malthus’s point in his Essay on the Principle of Population - eBook - ePub

Global Population Policy

From Population Control to Reproductive Rights

- Paige Whaley Eager(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 2 Population Control as Global PolicyIntroduction

This chapter will explore how Population Control, as the dominant norm guiding global population policy, was diffused internationally from 1965 to 1973. The United States, as an actor with agency, effectively propagated the norm of Population Control as critical to third world development from the period of 1965 to 1973. Through the Population Control establishment, which was largely based in the United States and a few other developed countries, the United States worked bilaterally and multilaterally to socialize other countries into accepting the need for Population Control measures. During this time, both the executive and legislative branches were in support of generously funding international Population Control programs. Moreover, domestic consensus within the United States supported the idea that development for the world’s poor would occur only when fertility rates began to decrease. Demographers, politicians, and the donor community supported Population Control measures without giving much thought as to how these policies affected women’s health and rights. Although resistance from the developing world was apparent in regard to implementing Population Control measures, the developing world had few avenues through which to express its views. For example, the 1965 gathering on world population in Belgrade, Yugoslavia was primarily attended by demographers and not governments. Only in 1974 would the international community have the opportunity to convene in a global forum to discuss world population and effectively challenge the norms the United States sought to disseminate, internationalize, and institutionalize regarding the causal relationship posited between population and development.Throughout human history, it was generally accepted that a growing population was vital to a society’s military and economic strength. However, by the mid-1960s, the ‘problem’ of rapid population growth, especially in the developing world, began to affect the institutions of the international system. The heretofore common stock of knowledge that a growing population is consistent with state strength began to be questioned. Moreover, the new ‘ideational structure’ that population growth can be negative, especially in the developing world, affected the interests and identity of the United States. The United States prior to the mid-1960s was adamantly opposed to becoming involved in the business of birth control within the United States, let alone in the developing world. However, by 1968 with the publication of the Ehrlichs’ The Population Bomb - eBook - ePub

- Manoj Sharma, Paul W. Branscum, Ashutosh Atri(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Jossey-Bass(Publisher)

Chapter 10 Population Dynamics and ControlThis chapter has been designed to give an overview of the field of population dynamics and control.Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to- Define basic terms pertaining to population dynamics and control.

- Explain basic nomenclature relating to family planning and contraceptive planning.

- Explain the four phases of the demographic cycle.

- Identify and explain the basic global population trends.

- Enumerate the different contraceptive options available, and comment on the comparable efficacy of each.

- Define fertility indicators and be able to enumerate and explain the different indicators covered in this chapter.

Demographic Cycle

The demographic cycle is the temporal evolution of the population of a geographically defined area (also known as the population cycle or the demographic transition). The socioeconomic history of industrialized nations closely informs the demographic cycle. Even though the name demographic cycle implies universality, it is essentially an idealized, composite picture of demographic changes in the industrialized world over the past few centuries. Whether or not these stages hold true, partially or fully, for the developing world remains to be seen. Four stages of population change have been identified in the demographic cycle (Figure 10.1 ).demographic cycle

The temporal evolution of the population of a geographically defined area (also known as the population cycle or the demographic transition ).demographic cycle

The temporal evolution of the population of a geographically defined area (also known as the population cycle or the demographic transition ).Demographic TransitionFigure 10.1Source: Photo downloaded from Wikimedia Commons, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8c/Stage5.jpgThe first phase of the demographic cycle is defined by high birth and death rates and a relatively low population. It has sometimes been called the high stationary - eBook - PDF

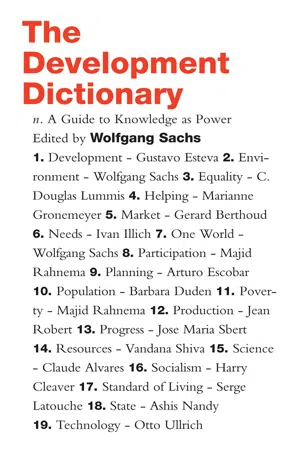

The Development Dictionary

A Guide to Knowledge as Power

- Wolfgang Sachs(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Zed Books(Publisher)

The new stress was on world population as a whole. A new logic moved to the fore. Paul Ehrlich argued, for example, that the earth’s ‘carrying capacity’ was endangered by population growth. Not the hope of development but the fear of global disaster gave a new motivation to the attempts at Population Control. Paul Ehrlich began his book: The battle to feed all humanity is over. In the /75. s the world will undergo famines – hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash program embarked upon.… These programs will only provide a stay of execution unless they are accompanied by determined and successful efforts at Population Control. The birth rate must be brought into balance with the death rate or mankind will breed itself into oblivion … Population Control is the only answer. 11 During the /75. s the people-versus-resources perspective took a hold of political reasoning. This perspective pits people against finite resources, and population comes to be seen as a factor that threatens the earth’s capacity to support human life. The United Nations Fund for Population Activities was created as a specialized agency in /747 and quickly its budget soared to $ / billion. The agency defined its task as exploring The complex ways in which population variables interact, reciprocally, with socio-economic development variables and to show how action programmes can be mounted to integrate population activities with health care, educational, rural development organization of agriculture, industrial development and other … programmes. 12 UNFPA prided itself on the ‘maturation and sophistication of population thinking [that] put an end to simplistic models’. 13 By the late /75. s popula-tion appears in policy statements as a variable in the algorithm to which the whole immensely complicated development process had been reduced. Population had become a variable analogous to capital, labour, technology or infrastructure in a ‘world system’. - eBook - PDF

The Environment

Science, Issues, and Solutions

- Mohan K. Wali, Fatih Evrendilek, M. Siobhan Fennessy(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

(From Vitousek, P. M. et al. 1997. Science 277:494–499). Human Population Growth 227 2005). A serious decline in food self-sufficiency already exists in developing countries. Cereal imports of 20 million tons in 1969–1971 by developing countries as a whole increased to about 112 million tons in 2000 (Sadik 1991). The overwhelming bulk of these deficits has so far been met by surpluses in North America, thus making world food security highly sus-ceptible to any variation in the performance of farmers and climatic conditions in that single region or to the use of crops for nonfood prod-ucts such as ethanol. Biophysical Controls over Population Growth Generally, demographic projections for coun-tries do not consider the controls over them imposed by local and global biophysical limi-tations. Exponential growth generated by positive feedbacks in a system cannot con-tinue indefinitely. In other words, there are always limiting factors and negative feed-backs to prevent the exponential growth of a system from going on forever; these are also known as limits to growth or the carrying capacity. For example, the presence of lim-ited food, water, energy, and land will eventu-ally constrain the well-being of social, natural, economic, and political systems so as to limit the human population. The size of a popula-tion takes the shape of “ S ” ( logistic growth ) over a longer period of time when the biotic potential (a maximum growth rate under ideal conditions) of that population is regu-lated by the limiting factors and the carrying capacity in a given area. Natural capital (resources) contains all the stocks of ecosystem goods and all the flows of ecosystem services upon which the survival and health of plants, animals, and humans depend (Table 11.3). Ecosystem goods and ser-vices provide productive, regulative, protec-tive, and cognitive functions for the well-being of humans and their surrounding natural and managed ecosystems.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.