Geography

Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami

The Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami occurred on March 11, 2011, off the coast of Japan. It was a powerful undersea megathrust earthquake that triggered a devastating tsunami, causing widespread destruction and loss of life. The event had significant geographical impacts, including coastal landform changes and the release of radioactive materials from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

Related key terms

1 of 4

Related key terms

1 of 3

10 Key excerpts on "Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami"

- eBook - ePub

Natural Hazards

Earth's Processes as Hazards, Disasters, and Catastrophes

- Edward Keller, Duane DeVecchio, John Clague(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

tsunamis . These destructive waves are commonly called “tidal waves,” but they are not tidal; the name is misleading. Tsunamis are common in some coastal regions and very rare in others. For years, scientists attempted to get public officials to expand tsunami warning systems outside the Pacific Ocean basin, but it took the catastrophe of the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 for governments and communities to take the tsunami hazard seriously. However, as often occurs after such catastrophes, translating increased awareness of a hazard into improved warning, preparedness, and mitigation is proceeding at a slow pace. This problem came into sharp focus on March 11, 2011, when a giant earthquake occurred beneath the seafloor off northern Honshu, Japan. The earthquake triggered a tsunami that reached elevations of up to 40 m above sea level along the northern Honshu coast and claimed more than 16 000 lives. It also caused meltdowns at three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant. This chapter explains tsunamis and assesses the hazard they pose to people. Your goals in reading this chapter should be to- ■ Know what a tsunami is

- ■ Understand the process of tsunami formation and propagation

- ■ Understand the effects of tsunamis and the hazards they pose to coastal regions

- ■ Know what geographic regions are at risk from tsunamis

- ■ Recognize the links between tsunamis and other natural hazards

- ■ Know what national, regional, and local governments, and individuals can do to reduce the tsunami risk

Giant Earthquake and Tsunami in Japan

The March 2011 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Honshu in Japan, also known as the 2011 Tõhoku earthquake, had a magnitude of 9.0.1 , 2 It is fourth largest earthquake in the world since modern record keeping began in the late nineteenth century. The earthquake triggered a powerful tsunami that reached heights of up to 40 m above sea level in Iwate Prefecture and travelled up to 10 km inland in the Sendai area (Figures 4.1 and 4.2 ).3The Japanese National Police Agency reported that the tsunami claimed nearly 16 000 lives, although this is likely an underestimate as 2800 people were still missing at the time this book was written.1 , 2 The economic toll was huge: more than 380 000 buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged and another 690 000 buildings were partially damaged. The World Bank estimated the direct damage from the earthquake and tsunami to be U.S.$235 billion, making it the most expensive natural disaster in history. Shortly after the catastrophe, Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan said, “In the 65 years after the end of World War II, this is the toughest and the most difficult crisis for Japan.”1 - eBook - ePub

Law and Disaster

Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Meltdown in Japan

- Shigenori Matsui(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 Tohoku Earthquake, tsunami, and aftermath2.1 The Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami 2.1.1 The Tohoku EarthquakeThe Tohoku Earthquake and the subsequent tsunami inflicted tremendous loss and damage. The government engaged in rescue and assistance operations for all victims. Various legal questions have been raised in the aftermath of the earthquake. They include questions on how to dispose of the remains of such a huge number of disaster victims, how to dispose of post-disaster debris, and how to dispose of automobiles and home electronic devices damaged by the tsunami. The aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami have also raised various questions relating to how assistance should be provided and what types of exceptional treatments can and should be extended to disaster victims. This chapter examines governmental response to these legal questions. It also examines why such devastating loss and damage had to happen and what was wrong with the preparation for the powerful earthquake and tsunami in Japan. This examination will show the serious failures of law in the preparation for and in response to the disaster and the deep-rooted failures of politics behind these failures of law.At 2:46 pm on 11 March 2011, an extraordinarily powerful earthquake rocked the Tohoku Region. The epicenter was 130 km off the Sanriku Coast, 24 km below the ocean’s surface.1 Its strength was unprecedented. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) initially reported the magnitude of the earthquake at 8.4 on the Richter scale but then upgraded it to 8.8 and, ultimately, to 9.0.2 Western research institutions now believe that the earthquake’s magnitude was 9.1.3 Many buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged. The earthquake was very powerful and was felt in many parts of Japan, even at great distances from the epicenter. Earthquake-triggered deaths even incurred in distant Tokyo and Kanagawa as well.4 - eBook - ePub

Asia in the New Millennium

Global Perspectives on the Earthquake, Tsunami, and Fukushima Meltdown

- Pradyumna P. Karan, Unryu Suganuma, Pradyumna P. Karan, Unryu Suganuma(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

Part 1Earthquake and Tsunami Damage

Passage contains an image

1

Historical Geography of the Japanese Tsunami

Unryu SuganumaJapan, one of the most advanced nations in the world and especially known for its high technology, has one of the best tsunami warning systems on earth (Oki and Koketsu 2011). The nation is famous worldwide for its ability to prepare against, train for, and mitigate damage from natural disasters. Nevertheless, Japan was not able to save lives during the ongoing triple disaster of earthquakes, tsunami, and nuclear radiation caused by the Sanriku Coast tsunami earthquake (named the Great East Japan Earthquake by the Japanese government) that took place on March 11, 2011. Some media and so-called experts in the Japanese media suggest that the 2011 Sanriku Coast tsunami earthquake was soteigai [unexpected], but this paper hints otherwise. Already two scientists (Tsuji 2011; Shimazaki 2011) have acknowledged their mistakes in predicting the tsunami earthquake in the Sanriku Coastal Region. Certainly, the experts cannot foresee everything in nature; however, the miscalculation by experts created additional human disaster on top of the natural disaster that occurred within the 2011 Sanriku tsunami. As a result of these miscalculations, the higher tsunami wall at Fukushima Daiichi that was originally planned was not built, and those living in the coastal area became careless about the tsunami warning systems. Almost no one expected this huge tsunami. If residents in the Sanriku region had known that an almost forty-meter-high tsunami was about to hit their area, they might have had a different mind-set and have been able to survive the catastrophic tsunami. Given these facts, the local residents have begun to learn lessons from the recent tsunami. In fact, five months after the 2011 disaster, the government of Miyagi Prefecture decided to launch 342 major recovery projects, including moving houses, schools, and hospitals to higher ground and constructing double-defense tsunami walls over the next ten years (Jiji News - eBook - ePub

Plate Tectonics and Great Earthquakes

50 Years of Earth-Shaking Events

- Lynn R. Sykes(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

I spent two months in Japan in late 1974 after visiting China for five weeks. I did much scientific and regular tourism throughout the country because it was my first visit. I took the train to Sendai in northeastern Honshu, which was struck later by a tsunami during the giant earthquake of 2011. Seismologists at Tohoku University were doing outstanding work locating earthquakes along their subduction zone. I visited Kyoto and Nagoya Universities on the bullet train from Tokyo. I was exhausted after many long days of visits to scientific labs and universities and long evenings of drinking with Japanese colleagues, all males. I took a long trip to the southern tip of the island of Kyushu to visit a very active volcano, Sakurajima. It welcomed me with several small explosions, a common occurrence. On my way back by train to Tokyo, I stopped for a day at Hiroshima. I returned to Japan two more times for meetings on earthquake prediction.Giant Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011While vacationing in Key West, Florida, on March 11, 2011, I awakened to scenes on TV of a tsunami (seawave) inundating the airport and city of Sendai along the Pacific coast of Japan. Japan’s largest-known earthquake in its long history of destructive shocks had generated this huge tsunami. The giant earthquake of magnitude 9.0 ruptured the subduction zone off northeastern Honshu, the main island of Japan. The maximum tsunami height was 133 feet (40.5 meters) with a wave that traveled up to 6 miles (10 kilometers) inland near Sendai, the major city of the region.More than 18,000 lives were lost in the earthquake and tsunami. The World Bank estimated the economic costs as U.S.$235 billion, the costliest natural disaster in world history. More than 127,000 buildings totally collapsed, and an additional one million were partially damaged. Longer-term financial losses have yet to be tallied from radioactive leakage, evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people, and ongoing attempts at cleanup from major explosions and meltdowns - eBook - ePub

- David Smawfield, Colin Brock(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan: The Immediate Aftermath Fumiaki EmaIntroductionChapter Outline Introduction Characteristics of the Great East Japan Earthquake The Disaster Culture of Tsunamis and the Role of Education Reports from Teachers in Ishinomaki Mental Care Issues The Nuclear Power Plant Disaster and Education Conclusion Questions for Further Consideration Suggestions for Further Reading ReferencesOn 11 March 2011, a 9.0 Magnitude earthquake struck eastern Japan. As of 16 November 2011, the official death toll has reached 15,839, with a further 3,467 people still missing. The mortality figure exceeds the 6,434 people that died in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, making what occurred in March 2011 the most devastating disaster in Japan since the end of World War II. The massive natural disaster completely transformed the landscape in affected areas. In the nine months that have since passed, the disaster has already led to the beginnings of a major review of previously accepted approaches to disaster preparation, response and recovery that had long been regarded as the norm in Japanese society. Among other things, the Great East Japan Earthquake has exposed problems regarding disaster prevention and energy use in post-war Japanese society. The contribution of this chapter will be to identify and examine some of the conditions faced by schools after the earthquake, based on interviews with teachers and other stakeholders who were affected by the earthquake. An attempt will then be made to identify educational issues for future disaster prevention and disaster mitigation at this time.To achieve all of the above, the following structure will be adopted. The chapter will consider in turn: key characteristics of the Great East Japan Earthquake; the disaster culture of tsunamis and the role of education; the school context, with particular reference to reports from teachers in Ishinomaki; mental care issues; and the nuclear power plant disaster and implications for the role of disaster education. An attempt will then be made to draw some key conclusions. - David Rothery(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Teach Yourself(Publisher)

On 9 March 2011 a M 7.2 earthquake occurred at a depth of 32 km in the subduction zone off the east coast of northern Honshu. It caused intensity V shaking in Sendai, but no real concern because it was not strong enough to cause a significant tsunami. For the next two days there was a declining series of aftershocks, and some relief was felt among seismologists because there was known to be an accumulation of strain on this part of the plate boundary, and it was possible that it had now been released in a non-damaging way.Then at 05:46 UT (14:46 local time) there was a bigger earthquake, at a depth of 32 km. It was initially reported at MW 7.9 but soon upgraded to MW 9.0 (Figure 11.10 ). This caused shaking of intensity VII in Tokyo and VIII in Sendai. Liquefaction was notable, but there were no casualties and little structural damage to modern buildings thanks to high engineering standards, though an oil refinery did catch fire. This became known as the Tohoku earthquake, taking its name from the northern region of Honshu that was the worst affected. Slip occurred on a 300 km length of the subduction zone, extending 150 km down dip. The maximum slip near the epicentre was 30–40 m, and Honshu’s location, as measured by global positioning (GPS) instruments shifted to the east by 2.4m. Figure 11.11 shows its epicentre, and the locations of the first aftershocks, which coincide roughly with the area of the thrust that moved.Figure 11.10 Magnitude plotted against time showing foreshocks (grey) and the main Tohoku earthquake and its aftershocks (white).Figure 11.11 Epicentres of the 11 March 2011 M 9.0 Tohoku earthquake (grey circle) and aftershocks exceeding M 6.0 over the next 24 hours. Sea-floor bathymetry is grey-shaded. The boundary between the Pacific plate and the plate carrying Japan is the grey line running along the trench.Even before these details were known, it was apparent that a megathrust earthquake of this sort of size would trigger a tsunami, and warnings were flashed over Japanese TV and social media (Figure 11.12- eBook - ePub

Everyday Life-Environmentalism

Community Sustainability and Resilience in Asia

- Daisaku Yamamoto, Hiroyuki Torigoe(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1Located in the Tōhoku region (in the north-eastern part of Japan), the Sanriku region stretches along the Pacific Ocean coast. Embracing a sea rich region with a large variety and rich catch of fish, its coastline, named the Rias coast, maintains a geographic vulnerability, which induces tsunami and amplifies their force of it. This geographic character of the coastline provides both rich fishing ground and tsunami, historically. Hence, not a small number of villages along the Sanriku coast have already lived through the devastating damages of tsunami repeatedly.In order to examine why people who have just experienced a tsunami may try to go back to the Sanriku coast, this chapter focuses on the case of one small community which lost 44 out of 52 homes, and more traumatically four villagers, to this most recent and utterly devastating tsunami of 11 March. An attempt will be made to understand the strategies of the inhabitants of coastal villages who, assumingly, somehow find the means to, or manners for, culturally interpreting and “domesticating” marine catastrophes into their community history. Upon this premise, this chapter starts with the “unusual day” the tsunami arrived and follows this damaged community’s decision-making process, leading toward a return to their “home.” Simultaneously, their “usual” days, which were suddenly disrupted, will be inevitably referred to in pursuing their reasoning to return to their native home.Sociological (and Anthropological) Approaches to Natural Disasters

In describing a community that tries to return to its original place near the sea despite having been devastated by a tsunami, a series of works by Yaichirō Yamaguchi cannot be ignored. Yamaguchi, while listening to every detail of the people’s ordinary days, walked through the villages of the Sanriku coast to research the damage, the evacuation process, and the resettlement patterns. In exploring the reasoning for their return to the coast, he describes the process of a community’s resettlement back to the seashore as follows. Although the villagers have at first resettled on higher ground after suffering the destructive force of a tsunami, people gradually start to move back to the original places one by one. For example, newcomers begin to settle back down in the formerly populated areas, which are much closer to the sea than the newly settled village areas that have been created in order to avoid future tsunami. However, when newcomers, who historically have a relatively higher mobility and lower income (Yamaguchi 2011 , 208), start to yield a richer catch of fish because of their close proximity to the sea, then tsunami victims, who were older inhabitants, once again start to move down to the coast, feeling that they are being deprived of the resources of their livelihoods (Yamaguchi 2011 - eBook - ePub

Geomorphology and Natural Hazards

Understanding Landscape Change for Disaster Mitigation

- Timothy R. Davies, Oliver Korup, John J. Clague(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- American Geophysical Union(Publisher)

9 Tsunami Hazards‘Tsunami’ is a Japanese word meaning ‘harbour wave’. This word entered the common lexicon following the catastrophic tsunami in the Indian Ocean that killed more than 250 000 people on 26 December 2004. Since this catastrophe, scientific attention to the phenomenon has skyrocketed, bolstering appraisals of tsunami hazard and risk (Løvholt et al. 2012 ). The tsunami triggered by the 2011 Great Tohoku earthquake, Japan, further spurred these research efforts and also prompted refinements to tsunami risk projections for Japan's coastlines (Cyranoski 2012 ). Tsunamis are trains of transient impulse waves in oceans or lakes that result from the sudden displacement of the water column by submarine earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, or meteorite impacts. The process is never a stand-alone one; tsunamis are always triggered by another process. Meteotsunamis are oceanic waves that form because of rapidly propagating changes in air pressure. They are surface waves, whereas ‘real’ tsunamis are body waves and thus are fundamentally different. They are rarely as destructive as their geologically triggered counterparts, but may cause water-level fluctuations in harbours of up to several metres (Renault et al. 2011 ).9.1 Frequency and Magnitude of Tsunamis

For most natural hazards, the amount of detail available for documented events decreases rapidly as we go back in time, and this holds particularly for tsunamis. One of the largest databases on past tsunamis is maintained by the NOAA National Center for Environmental Information and features more than 26 000 run-up measurements that were recorded for nearly 2600 tsunamis throughout the world, ranging from Paatuut, Greenland, to Scott Base, Antarctica, and going back some 4000 years (ngdc.noaa.gov/hazard/hazards.shtml,). Yet half of these records relate to tsunamis that occurred after 1996, and 24% of all entries (more than 6000) were on the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. Japan is prominently represented in this database, featuring 44% of all data locations, closely followed by the United States, Chile, and Indonesia. Hence the censoring of older events is accompanied by a strong geographic bias of past tsunamis. - eBook - ePub

- Chennat Gopalakrishnan, Norio Okada(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Table 1 , which documents the deadliest Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Pacific tsunami events in recorded history. Tsunamis are very common over the Pacific Ocean because it is surrounded on all sides by a seismically active belt. For example, the 1868 tsunami that occurred in northern Chile led to over 25 000 deaths. Devastating tsunamis have affected all the main Japanese islands, destroying hundreds of villages. In the 20th century alone, at least six major earthquake-generated tsunamis have occurred in Japan, including the 1896 event on the main island of Honshu (killing over 27 000) and the March 1933 tsunami in Sanriku (approximately 3000 deaths). Additional destructive tsunami events in Japan occurred in 1944, 1946, 1960, and 1983. The Hawaiian islands have also been repeatedly affected by tsunami events, such as the April 1946 event that inundated the city of Hilo and led to 171 deaths.Table 2 provides a listing of all major tsunami events in the Indian Ocean since 1850. The first three columns in Table 2 provide data relevant to the date of the tsunami event. The fourth and fifth columns provide information about the Indian Ocean country, state, province, or island where the tsunami source occurred. The sixth column provides the earthquake magnitude (valid values range from 0.0 to 9.9) while the seventh column provides information on the focal earthquake depth (in km). The eighth column (deaths) provides information on the numbers of deaths resulting from the tsunami. This figureTable 1 Deadliest tsunami events by regionSource : Tsunami Laboratory of Novosibirsk (2005) and USGS (2005).may also include deaths from the earthquake that triggered the tsunami. Table 2 shows that Indonesia is particularly vulnerable to tsunamis (generated by earthquakes and volcanoes): sitting on a Ring of Fire, the islands in the archipelago lie so close to colliding tectonic plates that waves may hit land before information arrives from deepwater buoys. For example, the August 1883 eruption of the Krakatau (Krakatoa) volcano in the Sunda Straits (between Sumatra and Java) generated a massive tsunami wave that killed over 36 000 Indonesians, causing an entire island to virtually disappear.The historical record of tsunami events dates back to antiquity, including the 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius (the oldest recorded tsunami in Italy). Following the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, systematic efforts to catalogue the locations of earthquakes (and the resulting tsunami events) were undertaken. Tsunamis leave their mark in historical, archaeological, and geological records in the form of features such as tsunami sand sheets in coastal marshes and turbidite deposits (a sand, silt, and mud sheet with highly distinctive characteristics). However, tsunami records face problems of completeness (significant areas such as Australasia were sparsely populated), distortion, and ambiguity, with respect to both the magnitudes of the tsunamis and their exact sources. However, recent advances in sea-bed mapping and the dating of tsunami deposits are enhancing the historical record. - eBook - ePub

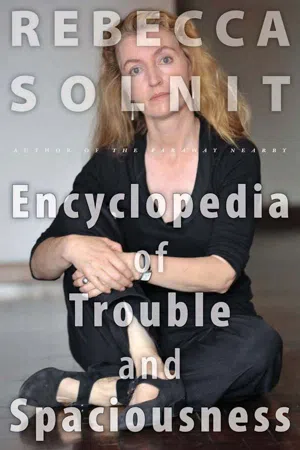

- Rebecca Solnit(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Trinity University Press(Publisher)

THE GREAT TŌHOKU EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMIAftermaths in JapanWhen I met him, Otsuchi city administrator Kozo Hirani, a substantial, balding man in a brown pinstripe suit, was on the upper floor of a warren of small-scale temporary buildings that now house the town’s administration. To reach him I had flown to Tokyo, taken a train more than three hundred miles north to Morioka, the capital of Iwate Prefecture, then got into a van with seven people from Tokyo’s International University who’d decided to see the disaster zone for themselves and help me while they were at it. Two were continental Europeans, five were Japanese, including one young man with the face of a warrior in a nineteenth-century Japanese print. His only job was to hand over exquisitely wrapped boxes—almost certainly containing some kind of sweet—in pretty shopping bags to everyone we visited, starting with Hirani. A huge cardboard carton of these items had been loaded into the van in which we traveled through the disaster zone.When the city administrator first saw the wall of black water coming at him, it was so vast and incongruous that he didn’t recognize it for what it was. Hirani survived the tsunami that swept the mayor and most of the small town’s higher-ranking officials away in the middle of the afternoon on March 11, 2011, leaving him with the burden of responsibility for the recovery of his town. “I lost five of my subordinates. One sank in front of me. It was twenty-four hours before the helicopters came,” he told me through an interpreter. “I was rescued by helicopter and when I saw the city from the sky I thought everything was at an end. It is very tough. My subordinates were in their twenties and thirties—I am fifty-five. Why did I survive?” Almost 10 percent of the town’s population of about 15,000 died in the tsunami, one of the highest per capita death tolls in the affected area along the northeast coastal prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima (which is the name of the prefecture as well as the inland city).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

Explore more topic indexes

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 6

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 4