History

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought from 1853 to 1856 between Russia and an alliance of France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia. It was sparked by religious and territorial disputes in the Middle East and the Black Sea region. The war resulted in significant loss of life and had long-term implications for European power dynamics and military tactics.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Crimean War"

- eBook - ePub

Messenger of Death

Captain Nolan & The Charge of the Light Brigade

- David Buttery(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

Chapter 5The Crimean War

The Crimean War was an unusual conflict and should have been avoided by diplomatic means. It was known more appropriately during the 1850s as the ‘Russian War’ since the Crimea was only one theatre of operations with important naval and land actions taking place in the Balkans, the Baltic Sea, White Sea and Pacific Ocean. However, the famous events that took place there and common usage have ensured that the conflict will always be known by this name. British involvement in the Crimea lasted for only two years, but the harsh lessons learned in the fight against Russia forced the government to reevaluate the organization of the armed forces. Following a long period of relative peace in Europe, a jingoistic public greeted the outbreak of war with unseemly enthusiasm. The Crimean campaign began with a series of dramatic actions that included three major battles in the latter half of 1854. Journalists, photographers and artists who travelled out to see things at first hand, recorded how the war subsequently became bogged down in the ruinous siege of Sevastopol, noted for the squalid conditions endured by both sides and for huge loss of life. They brought the sober reality of war back home to the public in a way it had not experienced before and this, along with innovations in weaponry, steamships and the use of railways, made it a transitional conflict between old and new. In many ways it was the first truly modern war.The origins of the war included a dispute over religious rights in the Holy Land. Much of the Middle East was under the sway of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, which allowed Christians access to the holy sites in Jerusalem. For many years custody of the Holy Sepulchre and other shrines had been disputed between the Roman Catholic and the Greek Orthodox Churches. Citing an old agreement, the French persuaded the Sublime Porte (the Turkish government) to give control of the holy sites to the Roman Catholics; Orthodox Russia was outraged. In 1852 Tsar Nicholas I of Russia applied diplomatic pressure on Sultan Abd-el-Mejid to return the keys of the Sepulchre to the Greek Church. Russian ambassadors used this issue as a pretext to champion the rights of Christian subjects in the Balkans, demanding concessions such as the withdrawal of Turkish troops from Montenegro. At an informal meeting at Tsarskoe Seloe, Nicholas made his views on Turkey very plain: - eBook - PDF

An Age of Neutrals

Great Power Politics, 1815–1914

- Maartje Abbenhuis(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

In this sense, for the British, the Crimean War was clearly about curbing Russian global power and protecting their own. The steps to war, however, were complex. At one level, they developed out of a dispute between the French, the Russians and the Ottoman sultan over the protection of Christian holy sites in the Ottoman Empire. As Orlando Figes argues, we should not underestimate the power of religion in explaining the context of the war. 13 At another level, the war grew out of Russian interference in the fate of the two Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. These were part of the Ottoman Empire bordering the Austrian Habsburg Empire, but their Christian of free trade Britain and fortress France: tariffs and trade in the nineteenth century’. Working Paper #142, Department of Economics, Washington University, January 1990. 10 D. R. Headrick, The tools of empire. Technology and European imperialism in the nineteenth century. Oxford University Press, 1981, pp. 174–5. For the implications of the geographic spread of empire on the peace-time responsibilities of the Royal Navy: C. J. Bartlett, Great Britain and sea power. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1963. 11 W. Baumgart, The peace of Paris 1856. Studies in war, diplomacy and peacemaking. Santa Barbara, CA, ABC Clio, 1981, p. xv. 12 P. W. Schroeder, Austria, Great Britain and the Crimean War. The destruction of the Euro- pean concert. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 1972, p. xii; Hamilton, ‘European wars’, p. 67. For more on the origins of the Crimean War: N. Rich, Why the Crimean War? A cautionary tale. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1991 (1985). Cf M. S. Anderson, The eastern question 1774–1923. New York, St Martin’s Press, 1966, p. 132. 13 O. Figes, Crimea. The last crusade. London, Allen Lane, 2010. 70 An Age of Neutrals subjects were under the protection of the Russian tsar. - eBook - ePub

The Victoria Cross Wars

Battles, Campaigns and Conflicts of All the VC Heroes

- Brian Best(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Frontline Books(Publisher)

Chapter 1

Crimean War, 1854–56

Number of VCs awarded 111 Number of VCs awarded to officers 41 Number of VCs awarded to other ranks 70 Total awarded to Royal Navy 24 Total awarded to Royal Marines 3 Total awarded to British Army 84 Origins of the War

The Crimean War was caused by long-term tensions that had developed in Europe since the signing of the Treaty of Vienna in 1814 after Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo. The objective of the Treaty was to restore old boundaries and preserve the status quo by upholding stable and orderly monarchies. The new Czar, Nicholas 1, reverted to an autocratic rule and an expansion of her empire.Russia began nibbling away at the Ottoman Empire and fought a series of wars on her borders beginning with Georgia, Chechnya, Armenia and Azerbaijan. She also cast her eyes to the east, and had reached the northern borders of Persia and Afghanistan, something that unsettled British India.In 1848, Europe was rocked by a series of revolutions which in the main affected France, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Poland and Italy. Britain and Russia were unaffected by this upheaval, although they were considerably uneasy about any spread over their borders. It did little to alter Russia’s ambitions to further expand to the south into Europe. Czar Nicholas was again casting covetous eyes at the ‘sick man of Europe’, Turkey, and the declining power of the Ottoman Empire. His ambition was to gain control of the Straits – the Bosphorus, Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles – to allow his Black Sea naval fleet access into the Mediterranean Sea. The most direct route was to advance through the Ottoman-ruled countries on the west of the Black Sea; Moldova, Rumania and Bulgaria.One of the beneficiaries of the 1848 uprising in France was Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who was elected President of the Second Republic. Within four years he felt strong enough to suspend the assembly and establish the Second French Empire, with himself as the new emperor, Napoleon III. As a usurper, he sought swift prestige to uphold his new ‘Second Empire’. - eBook - ePub

Why Wars Widen

A Theory of Predation and Balancing

- Stacy Bergstrom Haldi(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

not occur are taken into account, the Crimean War reasonably supports the thesis. Moreover, the Crimean War clearly undermines the alternative arguments.NOTES

1 . L.Thouvenel, Nicholas I et Napoléon III: Les Préliminaires de la Guerre de Crimée 1852–1854 d’après les Papiers Inédits de M. Thouvenel (Paris: Ancienne Maison Michel Levy Frères, 1891), p. 215.2 . Sweden joined the coalition too late to enter the fighting and is not considered a combatant in the war.3 . See Paul M.Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London: The Ashfield Press, 1983), pp. 171–2.4 . Members of the Russian Orthodox Church. Orthodoxy was the official religion of Russia and was even a state department.5 . The Convention of Balta Liman was signed in 1838; under it Britain won extensive tariff concessions and opened up the Ottoman Empire to British trade. See Ann Pottinger Saab, The Origins of the Crimean Alliance (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1977), p. 3. Turkey was Britain’s best trading partner in the region. See Andrew D.Lambert, The Crimean War: British Grand Strategy, 1853–56 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), p. 3; David Wetzel, The Crimean War: A Diplomatic History (Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, distributed by Columbia University Press, New York, 1985), p. 15.6 . A customs union of north German states. See Paul W.Schroeder, Austria, Great Britain, and the Crimean War: The Destruction of the European Concert (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), p. 4.7 . See ibid., p. 23.8 . For all of the details, especially regarding Austrian mediation attempts, see ibid. For the Ottoman perspective, see Saab, The Origins of the Crimean Alliance.9 . Saab, The Origins of the Crimean Alliance, p. 96.10 - eBook - ePub

Beyond Nightingale

Nursing on the Crimean War battlefields

- Carol Helmstadter(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

1The wider context of military nursing in the Crimean War

IntroductionIn many ways the Crimean War was the first of the new industrial wars, but it also retained many characteristics of the old ‘gentlemanly war.’ Diplomacy played a major role and prevented it from becoming a more generalized European war. ‘In contrast to the wars of the twentieth century, but in common with most European wars in modern history up to the nineteenth century,’ diplomatic historian Winfried Baumgart wrote, ‘the outbreak of the Crimean War did not stop the frantic and continuous diplomatic activities of the belligerent powers.’ The concept of unconditional surrender demanded in World War II, which leaves little room for compromise and makes diplomacy irrelevant, did not exist in the 1850s. Diplomats continued trying to find a means of making peace throughout the war. Moreover, all of the armies involved respected some of the old rules of warfare, and a certain sense of chivalry still remained.There are numerous examples of this kind of gentlemanly war. Truces to clear the wounded and dead from the field were frequent. Count Osten-Sacken, latterly the commanding general in Sevastopol, expressed in the most flattering terms his great admiration for the courage of the French troops. He had French prisoners buried with all the honors which he said were owed to their exemplary bravery. The Baron de Bazancourt, the official French historian of the war, deemed Osten-Sacken ‘a true and knightly gentleman.’1 The Russians treated prisoners well. A British colonel taken prisoner lived comfortably in a Russian general’s home,2 and from time to time a British aide-de-camp went into Sevastopol under a flag of truce taking letters from Russian officers who were British prisoners and bringing money, letters, and baggage to British officers who were Russian prisoners.3 The French also took a chivalrous attitude toward the enemy. Major Jean François Herbé, a ten-year veteran and St. Cyr trained officer, admired the courage and valor of the Russian officers who led sorties into the French trenches. They fought ‘with a vigour and intrepidity to which we must render homage,’ he said. Two days after a major sortie, when an armistice was declared to collect the dead and those wounded who were still alive, French and Russian soldiers, subalterns, and officers all shook hands, congratulated each other on their fighting prowess, and exchanged tobacco and cigars. Herbé thought that no one would ever have guessed that these men, only a few minutes earlier, had been trying to kill each other.4 - eBook - PDF

Russia and the West from Alexander to Putin

Honor in International Relations

- Andrei P. Tsygankov(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Nesselrode called the defeat a national humiliation of the first order. 45 Russia was no longer viewed as a major European power, because it now “carried less weight in European affairs than any time since the end of the Great Northern war in 1721.” 46 In addition, as a Russian historian wrote, “the entire southern border Russia in the Black Sea area was revealed as defenseless.” 47 202 Honor and Assertiveness The Crimean War, 1853–1856: Timeline 1852 December Sultan grants France special privileges to the Holy Places 1853 January Nicholas’s conversation with the English ambas- sador March-May Menshikov’s mission to the Sultan June British and French fleets arrive at Besika Bay July Russia moves to occupy the Romanian principalities August Proposal of the Austrian foreign minister Count Buol September Britain rejects Buol’s proposal British and French fleets pass through the Dard- anelles October Sultan declares war on Russia and sends troops across the Danube November Nakhimov destroys Turkish fleet in Sinop 1854 January Nicholas sends Count Orlov to Vienna February Britain and France give the Tsar an ultimatum to leave the principalities March Britain and France formally declare war on Russia April Austria and Prussia sign an alliance of neutrality June Austria negotiates with Turkey on the occupation of Wallachia and Moldavia July Russia defeats Turkey in the Caucasus August Russia withdraws from the principalities September Russia loses the Battle of Alma and begins fortifica- tion of Sevastopol 1855 March Russia breaks off negotiations in Vienna September Russia orders destruction of ships and ammunition in Sevastopol December Austria gives Russia an ultimatum to stop fighting 1856 January Russia accepts the Austrian ultimatum February-April Paris congress imposes conditions on Russia Explaining the War Europe’s opposition to Russia’s policies in the Balkans, combined with Nicholas’s firm sense of moral confidence in his actions, produced the conditions for a political conflict that was ultimately resolved through the use of force. - eBook - ePub

Beacon Lights of History, Volume 10

European Leaders

- John Lord(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The object, therefore, for which England and France went to war--the destruction of Russian power on the Black Sea--was only temporarily gained. From three to four hundred thousand men had been sacrificed among the different combatants, and probably not less than a thousand million dollars in treasure had been wasted,--perhaps double that sum. France gained nothing of value, while England lost military prestige. Russia undoubtedly was weakened, and her encroachments toward the East were delayed; but to-day that warlike empire is in the same relative position that it was when the Czar sent forth his mandate for the invasion of the Danubian principalities. In fact, all parties were the losers, and none were the gainers, by this needless and wicked war,--except perhaps the wily Napoleon III., who was now firmly seated on his throne.The Eastern question still remains unsettled, and will remain unsettled until new complications, which no genius can predict, shall re-enkindle the martial passions of Europe. These are not and never will be extinguished until Christian civilization shall beat swords into ploughshares. When shall be this consummation of the victories of peace?AUTHORITIES.A. W. Kinglake's Invasion of the Crimea; C. de Bazancourt's Crimean Expedition; G. B. McClellan's Reports on the Art of War in Europe in 1855-1856; R. C. McCormick's Visit to the Camp before Sebastopol; J. D. Morell's Neighbors of Russia, and History of the War to the Siege of Sebastopol; Pictorial History of the Russian War; Russell's British Expedition to the Crimea; General Todleben's History of the Defence of Sebastopol; H. Tyrrell's History of the War with Russia; Fyffe's History of Modern Europe; Life of Lord Palmerston; Life of Louis Napoleon.LOUIS NAPOLEON.

1808-1873. THE SECOND EMPIRE.Prince Louis Napoleon, or, as he afterward became, Emperor Napoleon III., is too important a personage to be omitted in the sketch of European history during the nineteenth century. It is not yet time to form a true estimate of his character and deeds, since no impartial biographies of him have yet appeared, and since he died less than thirty years ago. The discrepancy of opinion respecting him is even greater than that concerning his illustrious uncle. - eBook - ePub

A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Collection

A One-Volume Abridgment by Christopher Lee

- Winston S. Churchill(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- RosettaBooks(Publisher)

The Treaty of Paris, signed at the end of March, removed the immediate causes of the conflict, but provided no permanent settlement of the Eastern Question. Russia surrendered her grip on the mouths of the Danube by abandoning Southern Bessarabia; her claims to a protectorate over the Turkish Christians were set aside; the Dardanelles were closed to foreign ships of war during peace, as they had been before the war; and Turkey’s independence was guaranteed by the Powers, in return for a promise of reforms which was not worth the paper it was written on. Russia accepted the demilitarisation of the Black Sea, but repudiated her undertaking when Europe was absorbed by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. For the time being her expansion was checked, but she remained unappeased. Within twenty years Europe was nearly at war again over Russian ambitions in the Near East. The fundamental situation was unaltered: so long as Turkey was weak so long would her empire remain a temptation to Russian Imperialists and an embarrassment to Western Europe.With one exception few of the leading figures emerged from the Crimean War with enhanced reputations. Miss Florence Nightingale had been sent out in an official capacity by the Secretary at War, Sidney Herbert. She arrived at Scutari on the day before the Battle of Inkerman, and there organised the first base hospital of modern times. With few nurses and scanty equipment she reduced the death-rate at Scutari from 42 per hundred to 22 per thousand men. Her influence and example were far-reaching. The Red Cross movement, which started with the Geneva Convention of 1864,1 was the outcome of her work, as were great administrative reforms in civilian hospitals. In an age of proud and domineering men she gave the women of the nineteenth century a new status, which revolutionised the social life of the country, and even made them want to vote. Miss Nightingale herself felt that “there are evils which press much more hardly on women than the want of the suffrage”. Lack of education was one, and she favoured better girls’ schools and the founding of women’s colleges. To these objects she devoted her attention, and by her efforts half the Queen’s subjects were encouraged to enter the realms of higher thought.Palmerston, though now in his seventies, presided over the English scene. With one short interval of Tory government, he was Prime Minister throughout the decade that began in 1855. Not long after the signing of peace with Russia he was confronted with another emergency which also arose in the East, but this time in Asia. India had been basking under the administration of the East India Company, with only a moderate degree of supervision from London. The Company had its critics in Parliament and elsewhere, but their words had little effect upon its practices. Suddenly there occurred a disturbing outbreak against British rule. - eBook - ePub

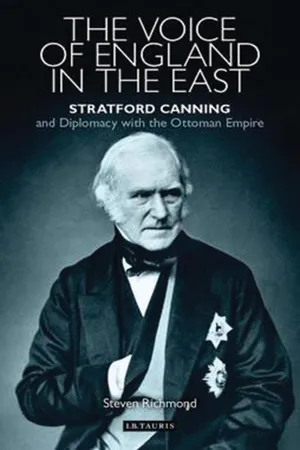

The Voice of England in the East

Stratford Canning and Diplomacy with the Ottoman Empire

- Steven Richmond(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

PART V THE Crimean War, 1853–56Passage contains an image CHAPTER 14 ‘HEAVEN HELP ME!’ 1

Believing or hoping he was ‘perhaps never to return’,1 Stratford Canning began a leave from his post and quit Constantinople for home on HM Steam Sloop Scourge on 22 June 1852.2 He was already planning to resign the embassy and this he achieved in London a few months later, in January 1853. He was now 66 years old and had arrived at retirement from diplomacy and a relaxed secondary career in the House of Lords. The previous year he had been raised to the peerage as Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe after having nearly been appointed Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the new government of the Earl of Derby.3 He seemed at this point to have finally realised his dream of settling at home. But suddenly world events intervened, his diplomatic career was reactivated, he was returned to Constantinople and his journey was back on.The Crimean War is renowned for beginning with the ‘Holy Places dispute’ between the French and the Russians over the maintenance of Christian religious sites in Ottoman Palestine. The dispute had actually begun in 1842 and ran perennially as a problem no one thought would ever be solved or would ever cause major trouble. While it was indeed important in contributing to the explosion of tensions in 1853, the real spark came not from Palestine but from Montenegro. In early 1852 the armies of the Ottoman general Omer Paşa had occupied this region in response to a nationalist uprising there. These troops remained through the year and there was talk of war between the Ottoman and Austrian empires. Tsar Nicholas wrote to the Austrian emperor, Franz Joseph, that: ‘If war by Turkey against Thee should result, Thou mayest be assured in advance that it will be precisely the same as though Turkey had declared war on myself.’ On 30 December 1852 the Russians mobilised two army corps in the Danubian Principalities along its border with the Ottoman Empire. And on 13 January 1853, the Russians undertook naval operations in the Black Sea and mobilised two more army corps in the region.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.