History

Decolonization

Decolonization refers to the process by which colonized nations gained independence from their colonial rulers. This often involved political, social, and economic transformations as former colonies sought to assert their sovereignty and establish self-governance. Decolonization movements were significant in reshaping global power dynamics and challenging the legacies of imperialism.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Decolonization"

- eBook - ePub

Decolonization

A Short History

- Jan C. Jansen, Jürgen Osterhammel, Jeremiah Riemer(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

1Decolonization AS MOMENT AND PROCESS“Decolonization” is a technical and rather undramatic term for one of the most dramatic processes in modern history: the disappearance of empire as a political form, and the end of racial hierarchy as a widely accepted political ideology and structuring principle of world order. One can pin down this historical process by using a dual definition that, instead of keeping the process chronologically vague, anchors it unequivocally in the history of the twentieth century. Accordingly, Decolonization is(1) the simultaneous dissolution of several intercontinental empires and the creation of nation-states throughout the global South within a short time span of roughly three postwar decades (1945–75), linked with(2) the historically unique and, in all likelihood, irreversible delegitimization of any kind of political rule that is experienced as a relationship of subjugation to a power elite considered by a broad majority of the population as alien occupants.1Decolonization designates a specific world-historical moment, yet it also stands for a many-faceted process that played out in each region and country shaking off colonial rule. Alternative attempts at a definition accentuate this second dimension. The historian and sinologist Prasenjit Duara, for example, puts less emphasis on the breakdown of empires and more on local power shifts in specific colonies when he defines Decolonization as “the process whereby colonial powers transferred institutional and legal control over their territories and dependencies to indigenously based, formally sovereign, nation-states.” He, too, adds a normative aspect: the replacement of political orders was embedded in a global shift in values. This dissolution signifies a counterproject to imperialism in the name of “moral justice and political solidarity.”2It is equally possible to ask, quite concretely and pragmatically, when the Decolonization of a specific territory was completed. A simple answer would be: when a locally formed government assumed official duties, when formalities under international law and of a symbolic nature were carried out, and when the new state was admitted (usually within a matter of months) into the United Nations. A more complex (and less easily generalizable) answer would weave these trajectories toward state independence into more comprehensive and intricate processes of ending colonial rule and extending political, economic, and cultural sovereignty. - eBook - PDF

Unreconciled

From Racial Reconciliation to Racial Justice in Christian Evangelicalism

- Andrea Smith(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

6 Decolonization IN UNEXPECTED PLACES Decolonization is intelligent, calculated, and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuate the subjugation and/or exploitation of your minds, bodies, and lands, and it is engaged for the ultimate purpose of overturning the colonial structure and realizing Indigenous liberation. . . . But make no mistake: Decolonization ultimately requires the overturning of the colonial structure. It is not about tweaking the existing colonial system to make it more Indigenous-friendly or a little less oppressive. The existing system is fundamentally and irreparably flawed. —Waziyatawin Angela Wilson and Michael Yellow Bird (2005, 5) Colonization is violence and violation of the most extreme sort. Colonization is theft and rape and murder and cannibalism on the grandest scale. Colonization is genocide. We should understand that there are indeed people with a heart for Decolonization in the churches, in business, even in the military as well as in schools, colleges and seminaries, even if . . . the systems themselves are . . . malignant, delivered over to the enemy as tools or weapons of colonization. Even so, it is not for us to somehow share power with the colonizers.—Robert Francis, Keynote Address, naiits Confer-ence, Rapid City, South Dakota (November 29, 2007) I n Native studies, many scholars propose “Decolonization” as a guiding principle for Native scholarship and activism. In the first epigraph above, from For Indigenous Eyes Only: A Decolo-nization Handbook , Waziyatawin Angela Wilson and Michael Yel-low Bird outline their understanding of Decolonization. They call DECOLONIZ ATION IN UNE XPEC TED PL ACES | 193 on community members and scholars to go beyond a politics of inclusion in order to build a world in which Native peoples are not governed under a settler colonial state. - eBook - PDF

The End of Empires and a World Remade

A Global History of Decolonization

- Martin Thomas(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Ideas of Decolonization Before grappling with the finality or incompleteness of empire collapse, it’s worth thinking about the specialist vocabulary to hand. Specialists may use ‘Decolonization’ as shorthand for the disintegration of modern overseas empires and transitions from colony to statehood. In the public Decolonization and the end of empires [ 15 ] sphere, though, Decolonization is more readily identifiable with something else: the crying need for an overhaul of public culture, from place names and statues to museum holdings, media, academic curricula, and political language.22 Within countries implicated in empire, slavery, and their legacies of racial discrimination, public calls to decolonize are bound up with the contemporary condition of those societies.23 Demands for Decolonization in this context turn on attitudinal change toward histories that societies, as refracted through their public institutions, laws, and police practices, their museums, monuments, and heritage sectors, find difficult to con- front.24 In shining a spotlight on police brutality and the cultural blind- ness of some public institutions to structural racism, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall have galvanized antiracist opposition to what they decry as colonialist behavior.25 People striving for ‘decoloniality’ empha- size the enduring tendency to construct social and societal differences— of ethnicity, of gender, of language and power—according to colonialist standards of modernity.26 The primary focus is not on what postcolonial scholarship situates as ‘historical colonialism’ but on hegemonic forms of colonialist thinking that inhibit the achievement of genuine postcolonial freedom.27 For others, studying empire is resonant because it speaks to the observed reality of persistent inequalities between rich world and poor.28 Often drawing on Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s ideas of biopoli- tics, in which colonized peoples were denied the freedoms necessary to more than a ‘bare life’ of subjugation, both perspectives read the immi- nence of colonialism in terms of contemporary injustice.29 Where do imperial and global historians fit in? For imperial historians, Decolonization is - eBook - PDF

Children and Young People's Participation and Its Transformative Potential

Learning from across Countries

- E.K.M. Tisdall, Andressa M. Gadda, Udi Mandel Butler, E.K.M. Tisdall, Andressa M. Gadda, Udi Mandel Butler(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Decolonizing then is also the complex process of disentangling coloni- alism’s consequences in the aftermath of national independence; even whilst the political governance of territories has been changed, colonial- ism has left deeply changed communities, particularly in their ways of speaking, knowing, relating and being in the world. 3 Decolonizing the Notion of Participation of Children and Young People Savyasaachi and Udi Mandel Butler Decolonizing Participation 45 How does children and young people’s participation relate to pro- cesses of colonialism (or post-colonialism) and Decolonization? As described in Chapter 2, children and young people’s participation has often been part of a broader field of international development. Over the last few decades a range of participation activities have been initi- ated by grassroots, national or international non-governmental organi- zations (NGOs) or government agencies across the world. Such projects have sought to encourage children and young people’s involvement in the area of education, health, environment, sports, arts and media. The most commonly mentioned spaces of children and young people’s participation are documented in the report for UNICEF The Participation Rights of Adolescents (Rajani, 2001). The report includes a table on ‘Common activities, roles and settings of young people’s par- ticipation’. The ‘institutional settings’ column includes: family, school, workplace, the street, media, youth organizations, international agen- cies, cultural or religious organizations, internet chat rooms, amongst others. In the ‘roles’ column the activities that children and young peo- ple practice within these various settings, which can be considered as different forms of participating, are listed: discussing and deliberating, speaking, culture-making, representing, advocating, planning, reason- ing, evaluating voting and so forth. - eBook - ePub

Decolonising the Study of Religion

Who Owns Buddhism?

- Jørn Borup(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Since then, the process of bringing transformations in international politics and values has been a major concern for engaged thinkers and actors, sometimes under the term ‘decolonisation’, a term still semantically evolving. That colonisation does not end by flag independence is a truism. Colonisation has lasting effects long after the end of empires with continuing structural inequalities and dependency on relations with the former colonial powers. In that way, the term decolonisation can be historicised as “a bundle of processes encompassing post-colonialism, second wave Decolonization, re-colonization 7 and decolonialization” (Thomas and Thomson 2018, 7). Frederick Cooper and Roger Brubaker identify a renewed interest in colonialism from 1980s with a” growing awareness that colonial societies could not be seen as ‘out there’ [and] a large portion of the world’s population via colonization profoundly shaped European as well as Afro-Asian history” (Cooper 2005, 34). The growing dissatisfaction amongst intellectuals’ own lack of possibilities of making social change further sparked interests in postcolonial orientation, not least in academia (ibid, 34–35). With the turn of the millennium, the accelerated communication networks with the internet spread globally, and the global village became more than a metaphor relativising the West as the centre of the world. The globalising effects related to transnational and -cultural circulation after the Fall of the Berlin Wall furthermore have triggered renewed discussions of decolonisation, as “globalization conditioned decolonisation, just as decolonisation shaped globalization” (ibid, 4). The experienced inequalities of lasting colonial effects – sometimes termed ‘coloniality’ – and lacking persuasions of the globalised world’s seductive narratives have been met with both glocal adjustments and post-global resistance, questioning the universality of global imaginaries. Figure 2.1 Imperial division - eBook - ePub

Trajectories

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies

- Kuan-Hsing Chen(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

To reformulate Hage's theoretical articulation at a general level: if the cultural basis of colonialism is racism, and its cultural strategy, assimilation, which generates an identification with the aggressor/colonizer, then can one say that the cultural basis of neocolonialism is multiculturalism (which recognizes differences but covers its dominant ethnic position as the nodal point of divide), and its cultural strategy, peaceful coexistence, and which generates an identification with the self in the form of nativism, civilizationalism and identity politics. The direction of an incomplete project of Decolonization is then to interiorize others in a highly self-conscious manner; here ‘others’ are not simply racial, ethnic and national categories, but also class, sex/gender and geographical positionings; the highly structured hierarchy of differences has to be transcended through interaction, understanding and changes of objective conditions.Colonialism is an imposed structure. From 1492 onward for four centuries, it radically transformed the world. The political epistemology of colonialism builds itself on a rigid ‘inside/outside’ distinction, and the main axes have been race and ethnicity: color, language, accent, religion, etc., mark the divide between the colonizer and the colonized; these are also cultural categories which mark hierarchies and unequal power relations. Sex, age and class in colonial relations were often metaphorized: colonizers are male adults with higher class positions, while the colonized were seen as women, and/or children with lower class status. Decolonization movements have deepened the understanding that an inversion of colonialism, a continuation of imposed colonial modes of thinking and categories turned upside down, would not answer. The political epistemology of Decolonization could no longer put priority on race and ethnicity under which sexual, age and class differences are subsumed. Recognition of differences, erasing the hierarchical structure of differences, and interiorizing differences are the principle of its political ethics. To put it simply, Decolonization is a permanent struggle against any form of domination.Ghassan Hage's insight pushes us to question the structural enunciative positions of the state apparatus, the power bloc, and the dominant culture in their handling of the problems of identity crisis: one might have good intentions but still generate the next wave of (neo)colonial domination. If that is the case, where can subaltern subjects go? - eBook - PDF

Africa since Decolonization

The History and Politics of a Diverse Continent

- Martin Welz(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2 | Decolonization and Liberation The Decolonization of Africa – a process, a strategy, and a political goal of the colonial powers that led the colonies and protectorates to become nominally independent and internationally recognized 1 – was not a straightforward matter, and is still not completed. When France at the outset of the twentieth century was bringing Morocco under its control, the end of the colonial era was already commencing at the southern end of the continent. We can speak of three stages of decol- onization. In the early phase of 1910–1922, only South Africa and Egypt had become independent; in the main phase (1951–1974), the vast majority of African countries gained their independence; and the late phase from 1975 was mainly characterized by the end of the Portuguese colonial empire and of the white minority governments in southern Africa. By the end of the twentieth century, all that was left of the once global empires of the European powers was “confetti.” 2 There are three perspectives from which we can look at decoloniza- tion: that of the colonial power, that of the colonial state, in other words the colony itself, and that of the international system. This chapter moves along these perspectives, identifies forces in the colonial powers, in the colonies, and beyond that played a role in making African states nominally independent, and shows that the decoloniza- tion was not a monocausal process. Independence here does not mean an all-encompassing liberation. For example, one can hardly speak of there being economic independence after Decolonization (see Chapter 3). The Perspective of the Colonial Power The perspective of the colonial power emphasizes the role of the colonial powers in the Decolonization and is thus Eurocentric. Proponents of this perspective argue that the rationally operating colonial powers liberated their colonies and their populations – after 23 they had been properly educated – into a self-determined modernity. - eBook - ePub

Political Geography

A Critical Introduction

- Sara Smith(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Chapter 8 Decolonizing Political Geography?- Power/Knowledge and Imperial Ruination

- World-as-System, Radical Dependency Theory, and Critical Development Studies

- Decolonization Begins With Thought – On Being Ethnographically Detained

- What Now? How Do We Decolonize?

- How Do We Decolonize? Abya Yala and Standing Rock

- What Have We Learned and Where Do We Go From Here?

Decolonization is a recognition that “a ghost is alive so to speak. We are in relation to it and it has designs on us such that we must reckon with graciously.”(Ramírez, in Naylor et al. 2018 , p.6; citing Tuck and Ree 2013 ; and Gordon 2008 )Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools. The metaphorization of Decolonization makes possible a set of evasions, or “settler moves to innocence”, that problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity.(Tuck and Yang 2012 , p.1)On the night of November 20, 2016, the US North Dakota Police used water cannons, teargas, and rubber bullets against Indigenous and allied protestors at one of the encampments near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation (Wong 2016 ). Several camps had been in operation since the summer of 2016, with citizens of more than 300 Native nations as well as other non‐Native allies holding this space in order to preserve Native sovereignty and defend the land against the potential environmental impacts of the Dakota Access Pipeline (Estes 2017 ). On the icy night that the water cannons were used, at least 300 people were injured, many by hypothermia, and 26 water defenders were hospitalized, with injuries including bone fractures and compromised vision due to rubber bullets (Wong 2016 - eBook - PDF

- Tatah Mentan(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Langaa RPCIG(Publisher)

In this regard, the nationalist revolution in China has this in common with all the struggles for Decolonization in Asia and Africa since 1945: all Decolonization struggles since the nineteenth century were made in the name of nationalism, which Fanon theorized in his classical The Wretched of the Earth (1961). Mao Zedong’s efforts attempted to turn 194 the nationalist revolution into the internationalization of communism. However, contrary to the Russian Revolution, Mao never left behind the millenarian history of China while the Russian Revolution made a drastic cut with the past and came empty handed: Russians were not Europeans and the Soviets, who enacted European theories of emancipation, did not have a history to back up their revolution. The history of the formation since the fifteenth century was cut and denied by the Soviets. Today’s Russia, with Vladimir Putin, turned the legacies of the Soviets into a State controlled capitalism but devoid of historical foundations while China has the legacies of Confucius and Mencius to refurbish national and moral values to confront the aggression of Western neo-liberalism and to detach themselves from Mao’s legacies. In a nutshell, coloniality (short hand for colonial matrix of power) was formed, transformed and controlled by Western imperial countries from 1500 to 2000. Today, dewesternization maintains the colonial matrix, but disputes its control, while decoloniality aims at transcending it. Hence, decoloniality means to undo and to overcome coloniality. In other words, decoloniality is epistemological focusing on decolonizing knowledge rather than territory. It is therefore the analytical task of unveiling the logic of coloniality and the prospective task of contributing to a world in which many worlds will coexist That is the most important difference with the way Decolonization was conceived during the Cold War. - eBook - PDF

Asia as Method

Toward Deimperialization

- Kuan-Hsing Chen(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

What distinguishes his work from that of his contemporaries is that he moved beyond unqualified celebration and gave a critical depth to the analysis of third-world national independence movements. After the withdrawal of the colonial master, is the psychoanalysis of Decolonization still useful? If Decolonization 1 so, what new problems are encountered? In this section, our analysis will focus on three different effects that have emerged during the decoloniza-tion process: nationalism, nativism, and civilizationalism. I want first to clarify my position. As historical products of Decolonization, these three responses and challenges to colonialism are widely spread throughout formerly colonized spaces. We, as critical intellectuals living in former colonies, have to recognize the power and legitimacy of these forms of Decolonization, each of which have had their respective moments in his-tory. Nationalism had an active, unifying function during the anticolonial struggles. Nativism brought people’s focus from the imperial centers back to their own living environments; in the process of reclaiming tradition, it tilted the balance away from the previous, sometimes worshipful em-brace of the modern. Civilizationalism, in providing a cultural-psychic cure for the colonized, challenged the superiority of Western-centrism and produced the ideal of mutual respect in a multicultural world. At the same time, we cannot afford to ignore the problems these decoloniza-tion effects have caused. Unlike those living in the imperial centers, our own existence is internal to the Decolonization movement. We do have to take analytical note—and have a sympathetic understanding—of the huge power exercised by third-world nationalism, nativism, and civiliza-tionalism. We also have to keep a critical distance from these effects in order to go on thinking reflexively, resist the temptation of resentment, and thereby arrive at a more balanced subjectivity. - eBook - PDF

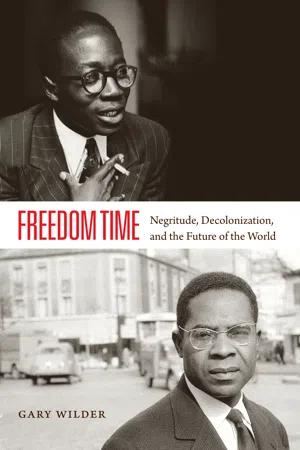

Freedom Time

Negritude, Decolonization, and the Future of the World

- Gary Wilder(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

NINE Decolonization and Postnational Democracy The pluralistic world is thus more like a federal republic than like an empire or a king-dom. However much may be collected, however much may report itself as present at any effective center of consciousness or action, something else is self-governed and absent and unreduced to unity. —William James The world-historical transformation known as “Decolonization” was simulta-neously an emancipatory awakening of peoples and a heteronomous process of imperial restructuring. Most actors and agencies on both sides, however, believed that territorial national states would be the elemental units of the post-war order. Former imperial powers, the United States, the UN, and the major-ity of non-European peoples whose social worlds had been brutally deformed by imperialism shared the assumption that self-determination meant state sovereignty. I have argued that Senghor’s and Césaire’s refusals to reduce decoloniza-tion to national independence derived from their convictions about the dif-ference between formal liberation and substantive freedom. Each proposed plans to reorganize his society, reconstitute France, and remake the global order. But neither adequately tethered his transformational vision to a dynamic social movement through which it could be realized. Both supervised political par-ties that, although seeking to channel popular demands, failed to express a people’s will, except in narrowly electoral terms. They each led massively popular political organizations whose constituencies felt little commitment to their lead-ers’ most cherished aims. This disconnect between constitutional initiatives and direct action was rooted equally in strategic blindness and untimely insight. Césaire and Senghor 242 · chapter Nine were canny political actors. Yet each gradually lost touch with the growing conviction among the global dispossessed that political independence was a necessary prerequisite for emancipation from colonial rule.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.