History

Freikorps

The Freikorps were paramilitary units composed of disaffected soldiers and right-wing nationalists in Germany after World War I. They were formed to suppress communist uprisings and maintain order, but they also engaged in political violence and played a role in the destabilization of the Weimar Republic. The Freikorps were eventually disbanded, but their legacy contributed to the political turmoil of the interwar period in Germany.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Freikorps"

- eBook - ePub

Hitler's Stormtroopers

The SA, The Nazis' Brownshirts, 1922–1945

- Jean-Denis Lepage(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Frontline Books(Publisher)

Part 2 Origins and Growth of the SturmabteilungPassage contains an image Chapter 7

The FreikorpsTHE MEN OF THE FREIKORPSAfter the collapse of the Second Reich in 1918, a national assembly was elected in January 1919 and met in Weimar the following month to draw up a new constitution, resulting in the creation of a democratic regime called the Weimar Republic. The black red and gold colours of 1848 were adopted for the new regime. By that time Germany was in the grip of social turmoil and near civil war, with Communists and Socialist parties clashing with various nationalist and conservative movements and militias.The Freikorps (Free Corps) were an important feature of German political life in the immediate aftermath of the war. Their history is little known but formed a major episode in the development of the nascent Nazi Party. The term Freikorps itself came from the ‘free corps’, irregular regiments of volunteer skirmishers created in Prussia during the Seven Years War (1756–63). They became famous for the part they took in the Battle of Freiberg against Austria in 1762. The Freikorps von Kleist was so successful that it was incorporated into the Prussian Army and consisted of jäger (light infantry), dragoons and hussars. The term was later re-used to designate the voluntary paramilitary formations organised by Major Lützow in 1813 as the kernel of an army to liberate Prussia from Napoléon. Continuing the tradition, the post-First World War Freikorps were right-wing paramilitary units recruited from ‘reliable’ officers and soldiers from the demobilised Imperial Army. The German troops returning home after the Armistice found their country torn apart by internal unrest and its eastern borders threatened by the Poles. Right-wing, nationalist and revanchist, the Freikorps became the available ‘force in being’ for the defence of the newly-created Weimar Republic. Though reluctant to support the new Republic, the Freikorps - eBook - ePub

The Devil's General

The Life of Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz, "The Panzer Graf"

- Raymond Bagdonas(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Casemate(Publisher)

Groener pledged the army’s support if Ebert was prepared to restore order. This the new Chancellor willingly agreed to do, asserting his bitter enmity towards the revolutionaries, regardless that many of them were socialists and former allies. Thus reassured, Ebert settled back to wait for the army to suppress the rebellion, saving both his government and Germany.The problem was, however, that the army was fast disintegrating. Only well-liked and popular officers had any control over their troops, and this was solely based upon shared front-line service and mutual respect. The vast bulk of the army could simply not be counted on. The answer was to gather whatever troops remained loyal into special units. So the Freikorps was born. Many of the first soldiers of the Freikorps were former members of the stormtroopers, specialised assault troops used to clear enemy trenches to pave the way for main attacks. They had a freebooting spirit and a singular loyalty to their officers, who shared with them a camaraderie born of great personal danger. Later, less disciplined troops and thugs attracted to violence would also join, giving the whole concept an unsavoury character.The Freikorps became a collection of unofficial military units varying in size from division to, more often, battalion or company strength, which supported the government temporarily to crush communists and other left-wing malcontents, and restore order. They were commanded by army officers ranging in rank from generals to captains, and it was to these officers that the men gave their first loyalty. Some were merely a collection of thugs and adventurers, although most were staunchly anti-communist, nationalistic, and a few perhaps even idealistic. However no matter what their composition or motivation, most disliked the socialist government but hated communism more. They were very often all the government had to ensure its survival.Although the revolution had spread to various parts of Germany, Berlin was the first priority of all sides. The Spartacists under Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg could bring the masses out on the streets, but thereafter often lost control. Unlike Lenin and his murderous cohorts in Russia, the German communists were badly organised, lacked clear aims, detailed plans and discipline. Nevertheless they remained a real threat to Ebert’s stumbling socialist government. - eBook - ePub

The Impossible Border

Germany and the East, 1914–1922

- Annemarie H. Sammartino(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cornell University Press(Publisher)

June and July 1919 marked a turning point for the Freikorps. Allied pressure increased after the capture of Riga in May and the retreat of the Bolsheviks shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, Latvian and Estonian forces combined to defeat Freikorps forces. Most devastating of all, however, the Ebert government agreed to the punitive terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Furthermore, when the Latvian government withdrew its promise of citizenship for Freikorps troops who wished to settle in Germany, Berlin did not force Latvia to accept the Freikorps as Latvian citizens. Faced with these betrayals, the Freikorps felt ever more distant from Germany. The radical nature of this break was revealed in the August mutiny of Freikorps forces under the command of Bischoff. These forces abandoned German control altogether to fight with White Russian General Avalov-Bermondt. But without access to fresh troops or supplies and facing a reinforced enemy, the alliance with Avalov-Bermondt quickly collapsed and the remnants of the Freikorps returned to Germany in late fall 1919.Resituating the Freikorps within its 1919 context makes the radical nature of the Baltic campaign more evident, along with the combination of hope, desperation, and violence it embodied. An almost postmodern disregard for the idea of the nation-state was accompanied by a shocking degree of violence. The Freikorps represented a particularly extreme version of the disarticulation of nation, state, and territory in postwar Germany, and the dual meaning of boundary and edge contained in von Salomon’s image of the border is apt not only as a metaphor for the Freikorps themselves but also for German society at that time more generally.What did it mean to be German after defeat, revolution, and territorial revisions? What shape would the borders of Germany have in the postwar and postrevolutionary era? The Freikorps’ proposed solution to the problem of the impossible border was not shared by most other Germans; however, in postwar Germany, not only the Freikorps were asking these questions.1. On the (relative success) of demobilization, see Richard Bessel, Germany after the First World War (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993). On the quick return to “normal” gender roles after the upheaval of war, see Ute Daniel, The War from Within: German Working-Class Women in the First World War, trans. Margaret Ries (New York: Berg, 1997). Dirk Schumann, Politische Gewalt in der Weimarer Republik 1918–1933: Kampf um die Strasse und Furcht vor dem Bürgerkrieg - eBook - ePub

- Peter Karsten(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

9Conditions in postwar Austria were ideal for the growth of paramilitary bands. The country was deeply divided politically and in danger of economic collapse. Furthermore, “the return of soldiers hardened by their experiences at the front … added to the population several hundred thousand uprooted and reckless men habituated to hatred and violence.”10 Consequently, the Austrian free corps movement was large and active.Soon after the end of hostilities, demobilized soldiers in rural districts formed local self-defense units. Led by former imperial officers and N.C.O.’s, Heimwehr formations either obtained arms from the government or stole them from depots. A similar group arose in Vienna. The Frontkämpfer Association, founded by an ex-officer, attracted not only war veterans, but also many students who could see no place for themselves in postwar Austria. At first neither the Heimivehr nor the Frontkämpfer Association had a clear political program beyond the desire to preserve wartime comradeship, attack Marxism, and perpetrate violence.11In 1919 and the early 1920’s the Frontkämpfer group engaged in numerous clashes with socialist defense units in Vienna and Lower Austria, while the Heimwehr developed extensive contacts with paramilitary leagues in Germany. Bavarian Free Corps groups supplied several Austrian formations with weapons, and Colonel Walde- mer Pabst, a participant in the Kapp putsch, fled to Austria and became chief-of-staff of the Tyrolean Heimwehr. Before becoming an important Heimivehr leader, Prince Starhemberg had served in the Bavarian Free Corps and had volunteered to fight in Silesia.12 Like German Free Corps leaders, Heimwehr - eBook - ePub

Night of the Long Knives

Hitler's Excision of Rohm's SA Brownshirts, 30 June – 2 July 1934

- Phil Carradice(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

The Nazis were not unique in developing paramilitary units. The Freikorps that seemed to proliferate at this time—the brainchild of ex-general Kurt von Schleicher, later chancellor of Germany—were just the tip of a very large iceberg. Free-standing gangs of men who could be put to any task, the Freikorps were right-wing units, violently and bitterly opposed to the communists, with whom they battled on a regular basis. Some Freikorps units, invariably made up of rootless ex-soldiers, were under government control and if so they were paid, usually through army sources. Others were affiliated to organizations like the Nazi Party. These were unpaid, unless the party managed to find funds to reward them, and ran the risk of being banned by the authorities if their activities became too violent.Hitler’s SA fell into this trap and they duly found themselves outlawed at one stage. It was only by the intervention of Franz von Papen who was attempting to curry favour with Hitler that the ban was eventually lifted.For sheer size, if nothing else, the Sturmabteilung, the SA or Brownshirts as its members were popularly known, was the most important paramilitary organization within Hitler’s Germany. Formed in the early days of the Party, the SA grew out of the strong-arm squads led by the ex-convict Emil Maurice. Their purpose, to begin with at least, was to protect Hitler and other Party members but, increasingly, they were used to disrupt the meetings of other political parties and to create a presence on the streets.Opernplatz, where the Nazis burned over 20,000 books on 10 May 1933. (Photo Jorge Láscar)Disguised for a time as the Gymnastic and Sports Division of the Party, on 5 October 1921 they formally became the Sturmabteilung. Out in the open now, the SA wore brown uniforms—in a direct ‘lift’ from Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirts in Fascist Italy—and, placed under the command of Johannn Ulrich Klintzich, began to contest and, eventually, claim power on the streets.These men happily carried out Hitler’s orders. Only once did he personally lead them in an attack on a rival political group when the speaker, a Bavarian by the name of Otto Ballerstedt, was administered a severe beating and Hitler found himself in prison again. Sentenced to three months, he served just one and emerged from his first experience of ‘common jail’ more popular than ever. As he told the police, the sentence had been worth it as the SA got what they wanted: Ballerstedt did not speak. - No longer available |Learn more

Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hitler

Germany's Generals and the Rise of the Nazis

- Alexander Clifford(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Pen & Sword Military(Publisher)

This resulted in the rapid recruitment of large Bavarian Freikorps units, as well as the deployment of Freikorps and Reichswehr troops from elsewhere, in order to crush the Munich Soviet. As we have seen, this they did, quickly and with much brutality in May 1919. The result of all this turmoil was that the political atmosphere in Bavaria, and Munich specifically, was super-charged, even in the context of the turbulent Weimar Republic. 126 Although the Freikorps’ triumph had allowed Hoffmann and the SPD to return to the state capital, the prime minister found that the army and security forces in Bavaria were infested with far-right Freikorps figures, who, in the chaos of the collapse of the Soviet, had established themselves in positions of power. Unlike Captain Ehrhardt in the north, the Bavarian Freikorps generalissimo, Franz Ritter von Epp, ensured he and his brigade were not disbanded but instead integrated into the local Reichswehr. His chief of staff Ernst Röhm became one of the most influential army officers in the region and one of Röhm’s main roles was procuring arms for right-wing militia units. 127 A prison governor who had sided with the counter-revolution, Ernst Pöhner, became Munich chief of police and he quickly set up a political department under Wilhelm Frick, one of the earliest members of the Nazi Party. The head of the Bavarian Reichswehr, General von Möhl, approved the controversial creation of an Einwohnerwehr, or Civil Guard. Headed by the monarchist Georg Escherich, ably assisted by Röhm, the Civil Guard was a civilian militia which had been recruited to help defeat the Munich Soviet. Its stated purpose was to defend Bavaria against any future uprising. Given that known leftists Conspirator: Ludendorff as Public Enemy Number One 55 were expelled from its ranks, it could hardly claim to be a genuine citizens’ defence organisation; evidently, the Civil Guard would not intervene against a rightist putsch. - eBook - ePub

Transnational Soldiers

Foreign Military Enlistment in the Modern Era

- N. Arielli, B. Collins, N. Arielli, B. Collins(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The German army was also heavily affected both by the outcome of the Great War and the Russian revolution. In the Baltic region its almost complete disintegration in late 1918 led to the replacement of regular units with volunteers. Their arrival was critical in stopping the Bolshevik advance into the Baltics, but also created a security problem for the Lithuanian and Latvian governments. Disheartened by Germany’s defeat in the Great War, weak economic prospects in post-war Germany and driven by their deep anti-Bolshevism, colonial desires and the need to reconstitute the fallen military prestige of Germany, the Freikorps turned out to be valuable military allies for the Baltic governments and hated foreign mercenaries for the local populations. Their unruly, adventurous nature, brutality, harsh treatment of civilians and, finally, their military defeat by the Baltic armies contributed to their controversial legacy. Their relationship with the Lithuanians went from an expedient military alliance and mutual suspicion to open hatred as their failure to achieve their military and political ambitions became evident.There is little doubt that in the post-World War I period various volunteer troops played a significant part in the course of the subsequent military conflict, constitution of new political entities and the formation of new identities in Europe. For Lithuanians the post-World War I episode of volunteering became a constitutive factor in building their nation-state. The military exploits of the Lithuanian volunteers swiftly entered a canon of national mythology of the interwar state, even if the volunteer troops were quickly replaced by regular conscripts. Today the Lithuanian volunteers are commemorated in the War Museum of the Grand Vytautas in Kaunas and their names can be found in history textbooks. The legacy of German Freikorps was extolled during the Nazi period in Germany and was happily invoked by the Nazis during Hitler’s invasion of the East in 1939. Today it remains a largely forgotten page in Germany’s history that warns about the dubious legacy of military volunteerism in the modern world.Notes1 . A new comparative approach to various post-World War I European conflicts was recently proposed by: Robert Gerwarth, ‘The Central European Counter-Revolution: Paramilitary Violence in Germany, Austria and Hungary after the Great War’ Past & Present, 200 (2008), pp. 175–209. See also: Alexander V. Prusin, The Lands Between: Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 1870–1992 - eBook - PDF

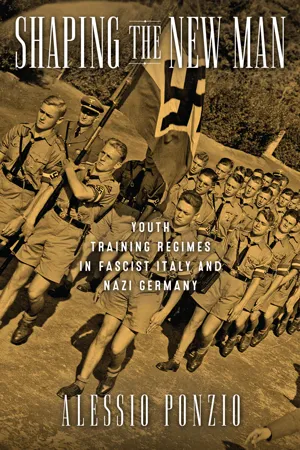

Shaping the New Man

Youth Training Regimes in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany

- Alessio Ponzio(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

76 4 And They Will Never Be Free Again, for the Rest of Their Lives I n Germany, as in Italy, the end of World War I meant the beginning of an inter- necine conflict among political enemies. Wartime attitudes continued brutalizing politics and heightening indifference to human life. The Freikorps—paramilitary units spontaneously formed after the war to put down Communist uprisings— symbolized the continuation of wartime camaraderie in peacetime. The “myth of war” shaped the identity of several radical groups that arose in postwar Germany. One of these groups, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, would change the course of history. 1 Both Fascists and Nazis glorified the war and considered it the beginning of the Italian and German national rebirth. More- over, both Mussolini and Hitler entrusted the task of guaranteeing the full realization of their revolutions to the younger generation. And in Germany, as in Italy, to fulfil this task the youth had to be educated. In general, the Nazi youth organization had a trajectory not unlike that of the Fascists. But the Hitler- jugend (HJ) in Germany and its Italian counterpart, the ONB, followed some- what distinct paths. Just as the history of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Partei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party, NSDAP) differed from that of the PNF, so too were there variations in the traditions of Italian and German youth associationalism, leading to diverse policies of youth train- ing under the totalitarian dictatorships. The Origins of the National Socialist Youth Movement: The Jugendbund der NSDAP When in 1920 Hitler announced at the Hofbräuhaus in Munich the program of the German Labor Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei), predecessor of the And They Will Never Be Free Again 77 NSDAP, leftist protesters tried to shout him down. - eBook - PDF

Hitler's Armed SS

The Waffen-SS at War, 1939–1945

- Anthony Tucker-Jones(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Pen and Sword Military(Publisher)

They told me there were 2,000 men waiting to join the corps, and Brig-General Patterson [acting Brigadier Parrington] of Crete, was waiting to take over. Hughes was sent to a Britische Freikorps billet where there were ten or twelve other men, including Eric Wilson of 3 Commando and a Canadian called Corporal Martin. In total 300 ‘volunteers’ were despatched to a Berlin ‘Holiday Camp’ for two or three weeks of indoctrination and education in 1943. However, only about fifty men were eventually deemed suitable to be granted full membership of the Britische Freikorps, including John Amery, Thomas Heller Cooper, Eric Durin (Duran), John Galaher, Edward Jordan, John White and an American called Lieutenant Tyndall. The Freikorps was run by the ‘Big Six’, who included Sergeant MacLardy of the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was a member of the BUF from 1934 to 1938 and was subsequently taken prisoner in 1940. In September 1943 he applied to join the Waffen-SS and it was allegedly on his proposal that the Britische Freikorps was set up. After preparing propaganda leaflets, he then applied to join the SS medical services. Eric Wilson was also alleged to have been at one time in control of the Britische Freikorps. Lance Corporal Nicholas Courlander, a Londoner serving with Hitler’s British Nazis 171 the New Zealanders, also claimed he had interested the Germans in the formation of the Freikorps. In early 1944 he set out on a recruiting tour, visiting some nine prisoner of war camps. After the allied invasion of France, he left the Britische Freikorps and joined the SS as a propagandist and war reporter. According to Courlander’s testimony, in 1945 the Nazis proposed setting up a provisional government in Britain and the Channel Islands. Arrangements had been made by the German Foreign Office for Amery to be a leading member. However, the plan was conditional on the Freikorps raising 1,500 men.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.