History

Gordon Brown

Gordon Brown is a British politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2007 to 2010. He was a key figure during the global financial crisis and implemented various economic policies to address the challenges. Brown's tenure was marked by his focus on international development and efforts to reform global financial institutions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Gordon Brown"

- eBook - ePub

The Brown Government

A Policy Evaluation

- Matt Beech, Simon Lee(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

A puzzle of ideas and policy: Gordon Brown as prime minister1 Matt BeechI don't recall all the sermons my father preached Sunday after Sunday. But I will never forget these words he left me with: ‘we must be givers as well as getters’. Put something back. And by doing so make a difference. And this is my moral compass. This is who I am. I am a conviction politician. I stand for a Britain where everyone should rise as far as their talents can take them and then the talents of each of us should contribute to the well being of all. (Brown 2007b, p. 4)And just as those who supported the dogma of big government were proved wrong, so to those who argue for the dogma of unbridled free market forces have been proved wrong. (Brown 2008, p. 2)Introduction

Gordon Brown as prime minister is a puzzle. Within his generation of Labour politicians he has arguably the keenest mind. He is an academic by training, and has written and edited a selection of books and essays on various aspects of Labour politics and history.2 This prime minister is by far the most intellectually literate of Labour leaders. However, since becoming prime minister Brown has failed to produce and expound a statement of his ideas and values. Moreover, he has not fully given a restatement of New Labour principles. Why is this the case? His tenure in office has been one of enormous pressure and is generally regarded as a poor start. Are these two factors in any way connected? This article argues that the connection between Brown's unconvincing leadership in the office of prime minister and the absence of a declaration of ideological intent is both real and of significant import, especially for a leader of the Labour Party.The problem

Tony Blair was the most electorally successful Labour prime minister but he was not renowned for his grasp of, or desire for, a robust understanding of Labour ideology. Yet in the following extract Blair appears to be making a statement of intent based upon certain ideas and describing a political mission for his government, something that Brown has strangely not provided: - eBook - PDF

Trio

Inside the Blair, Brown, Mandelson Project

- Giles Radice(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

Brown survived partly because there was no obvious successor. Brown told a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party the following Monday that he had his strengths and his weak-nesses – and that he would try to address his weaknesses. Mandelson’s speech to the 2009 Labour Party conference at Brighton in September was a tour de force and, for the first time, he was given a standing ovation. It was witty, moving and rousing. Accepting that Labour was the underdog in the coming election, he said to the cheering dele-gates, ‘If I can come back . . . we can come back.’ Afterwards Blair exchanged text messages with him about finally being loved by the party. It had taken a political and economic crisis to turn the former ‘Prince of Darkness’ into a conference hero. The question was was it too late? Brown in Trouble – Mandelson Returns 217 17 CREDIT CRUNCH – BROWN HELPS ‘SAVE THE WORLD’ O n 21 March 2007, Gordon Brown delivered his last budget as Chancellor before becoming Prime Minister. In it, he repeated, with more than a touch of hubris, the words he had spoken, to the intense irritation of the Tory opposition, more than a hundred times in the Commons between 1997 and 2007: ‘We will never return to the old boom and bust.’ 1 On the face of it, he was justified in being proud of the record of the economy under his stewardship. ‘I can report the British economy is today growing faster than all the other G7 economies – growth stronger this year than the euro area, stronger than Japan and stronger even than America,’ he proclaimed. For more than a decade, the British economy had grown with national output increasing by a third. What was equally remarkable was that inflation, in the past the UK economy’s Achilles heel, had gone up annually by only 1.5 per cent. Living standards rose steadily. Public spending had increased by 4 per cent in real terms between 1999/2000 and 2007/08 (with much of it going into health and education), faster than the long-run growth rate 218 - eBook - PDF

Welfare Policy Under New Labour

The Politics of Social Security Reform

- Andrew Connell(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

The position of Gordon Brown in the Labour Party, 1994–97 The development of Brown’s influence in the Labour Party in the 1980s and 1990s has been well documented by his biographers (see, for example, Bower 2004; Routledge 1998; Naughtie 2001). After building a position in the Scottish Labour Party in his 20s and standing unsuccessfully at the 1979 General Election (ibid.: 230), Brown entered Parliament in 1983 and shortly afterwards began to share an office with Tony Blair. From very early in their parliamentary careers, Brown and Blair were bracketed together (for example, Clark 1994: 54), with Brown being generally seen as the senior of the two until about 1993 (Naughtie 2001: 49–53). In 1985 Brown was appointed to the Opposition front bench as a junior Trade and Industry spokesman (ibid.: 320), having earlier refused an appointment to the shadow Scottish Office team in order to have a wider sphere of activity (ibid.: 33). In 1987 he was elected to the Shadow Cabinet, and appointed Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury under John Smith, the then Shadow Chancellor (ibid.: 38). During Smith’s absence from Parliament after his first heart attack in 1988 Brown deputised for him, and made a name for himself as a particularly formidable opponent of Nigel Lawson, the then Conservative Chancellor. He returned to the Trade and Industry team as Shadow Secretary Welfare Reform and the Thinking of Gordon Brown 93 of State in 1989 (ibid.: 321) and, after Smith’s election to the leadership, became Shadow Chancellor in 1992, continuing to hold that post until he entered the Treasury in 1997. He had thus, by 1997, spent his entire front-bench career shadowing the two key economic departments. This would be an important factor in the development of his thinking on welfare policy. - eBook - ePub

The imperial premiership

The role of the modern Prime Minister in foreign policy making, 1964–2015

- Sam Goodman(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

8 Gordon Brown, 2007–10 On 27 June 2007 Gordon Brown fulfilled his lifelong ambition and ascended to the premiership. After ten years of coveting the job and at least five spent actively pursuing his predecessor to step down, he had reached the threshold of No. 10. Effectively elected unopposed as Labour Party leader he was at the height of power. As Andrew Rawnsley in his book The End of the Party: the Rise and Fall of New Labour 1 rightly points out, on paper no Prime Minister in modern times entered No. 10 better qualified or prepared for the role. Brown had had a decade to think about what he wanted to do as Prime Minister, nearly a year's notice that there would be a vacancy with Tony Blair's departure, and six weeks of a formal transition to plan for his arrival. He would be the first person since Anthony Eden to become prime minister without any competition. 2 This was ultimately down to the belief amongst many backbenchers, who were strong supporters of Brown, and even Blair himself, that Brown was somehow owed the premiership. Blair still held a level of guilt over the perception that in 1994 when he ran for the leadership he supplanted Brown, his senior partner. This belief among supporters of Brown's claim was matched by a sense of inevitability about a Brown premiership. Many of those floated as potential rivals ruled themselves out, fearing that to run against Brown would surely end in failure and be political suicide. Brown's new dominance was not confined to the Labour Party. As Prime Minister he quickly set about culling the Cabinet he inherited from his predecessor. No less than nine members of Blair's final Cabinet resigned or were sacked or demoted. 3 In their place he promoted loyalists with relatively little Cabinet experience. Jack Straw and Alistair Darling were the only 1997 veterans, who like Brown, had served in Cabinet for ten years - eBook - ePub

The Prime Ministers

Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to Johnson

- Steve Richards(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Atlantic Books(Publisher)

At the other end of the scale, Gordon Brown was deeply unlucky in terms of the background against which he made his moves. Indeed, he faced profoundly challenging dilemmas throughout his career. There was no junction where he, or an objective observer, could look up at the wider political scenery and fully enjoy the view. Instead the view tended to be dark, with immense, complex political or economic challenges, even when he inherited a partially benevolent economy as chancellor in 1997. Part of the darkness was formed by Brown’s internal critics, who tended to ignore the challenging background in which he made his cautious, calculating and sometimes daring moves. His angry Labour opponents often surfaced to comment anonymously on how useless Brown was, without suggesting how they would apply their apparently masterful skills to the intimidating tasks at hand. This pattern applied when Brown was shadow chancellor, chancellor and then prime minister.The fate of leaders is determined partly by how they rose to the top: Wilson bringing together a Labour Party deeply divided in the vote-losing 1950s; Heath’s successful ministerial career giving him a misplaced confidence; Callaghan’s close relationship with the trade unions; Thatcher’s speedy ascent as she pledged to abolish the local property tax; Major’s equivocal positioning in the Conservative Party; Blair’s conviction that Labour wins only by being ‘new’. Both Blair and Brown were defined by their early years as MPs in the party’s vote-losing years of the 1980s and early 1990s. All leaders are also shaped by their less overtly political early years, from Thatcher’s upbringing in Grantham, to Major’s in Brixton. Of all the modern prime ministers, Brown surfaced from his early years most fully formed, with his qualities and deep flaws. His father was a minister in the Church of Scotland, a figure that Brown cited as often as Thatcher referred to Alderman Roberts. Brown suggested that his father gave him his moral compass. His father sought to do good in the Church. Brown saw politics as the vocation in which he could make a difference to people’s lives. At the same time, he became a youthful star in the Scottish Labour Party, once described by another sparkling figure from Scotland, Robin Cook, as a ‘nest of vipers’. Cook, who became Foreign Secretary in the New Labour era, was one of several figures Brown fell out with. Brown learned that politics could be brutal, and sometimes should be brutal. For Brown, the ends justified the means, whether the end was his own ascent to the top of the Labour Party or prevailing with colleagues in order to pursue causes related to his interpretation of social justice. - eBook - PDF

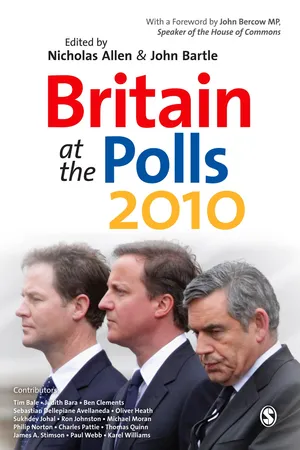

- Nicholas Allen, John Bartle, Nicholas Allen, John Bartle(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

Great expectations In 2005, many disillusioned supporters had held their nose and voted Labour, comfortable in the knowledge that they would ‘vote Blair, get Brown’. 23 There was widespread hope in the party that Gordon Brown, when he became prime minister, would provide the government with a renewed and improved sense of direction. This hope rested on three foundations. The first was Brown’s immense reputation as chancellor of the exchequer. Brown had presided over a booming economy since May 1997. Unusu-ally for a Labour chancellor, Brown had also won the confidence of the City and the financial markets. But his reputation did not extend solely 7 Labour’s Third Term: A Tale of Two Prime Ministers to macro-economic management. As chancellor, he had initially reined in public spending before rapidly increasing the money available to pay for schools and hospitals in the 2000 comprehensive spending review. He had also used his position in the Treasury to determine large measures of domes-tic policy, especially in the field of social security, through his tax-credit schemes. In a 2006 survey of British political scientists, Brown was judged to be the most successful post-war chancellor by a country mile. 24 The second foundation of Labour’s optimism was the expectation that Brown’s leadership would be more in tune with the party’s traditions and ethos than Blair’s. Even though Brown had been Blair’s co-architect in the creation of New Labour, and even though the policy differences between them were difficult to discern, Brown was thought to be closer to Labour’s ideological heart. Labour party members tended to regard Blair as a centrist or even right-of-centre politician and Brown as a left-of-centre politician whose views were much closer to their own. Such perceptions were partly a consequence of many in the party wanting or needing to believe that this was the case. They were also a consequence of what Brown said and did. - eBook - PDF

A Century of Premiers

Salisbury to Blair

- D. Leonard(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The most controversial of these was the abolition of tax relief on the investment income of company pension schemes. Brown used the yield from these taxes to increase benefits skewed towards people on low incomes, and the redistributive effect was probably as great as it would have been if he had been in a position to raise the maximum income tax rate. Although he was criticised for attempting too much ‘fine tuning’ in his Budgets and welfare policy changes, few would question that Gordon Brown was one of the most, if not the most, successful post-war Chancellors of the Exchequer. His record was summarised in the follow- ing terms by the authors of the 2001 Nuffield Election Survey, normally regarded as impartial observers: Inflation stayed below 3 per cent, GDP grew annually by about 2.5 per cent over the next four years. Opposition prophecies of doom were refuted regularly by the monthly economic statistics. Unemployment fell from 1.9 million in 1997 to under 1 million in 2001. Gordon Brown was able to boast of his achievement in paying off a sizeable proportion of the national debt, helped by buoyant tax A Century of Premiers 356 revenues and by £22bn from the sale of digital channels in 2000. £34 bn of government borrowing was paid off and debt servicing fell from 44 per cent to 32 per cent of government expenditure. (Butler and Kavanagh 2002, p.2) In addition, and for the first time ever, Britain’s economic performance, as measured by the usual indicators, was better than that of the European Union as a whole. If economic and social policy had largely been subcontracted to Brown, Blair himself certainly kept close control over the various con- stitutional changes which figured prominently in his first term. Devolution to Scotland and Wales was quickly legislated and was approved by a large majority in a referendum in Scotland, but by only a slender one in Wales.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.