History

Grenville Acts

The Grenville Acts were a series of laws passed by the British Parliament in the 1760s, including the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts. These acts were designed to raise revenue from the American colonies to help pay for the costs of the French and Indian War. They were met with strong resistance from the colonists and contributed to the growing tensions that led to the American Revolution.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Grenville Acts"

- eBook - PDF

The Intellectual Life of Edmund Burke

From the Sublime and Beautiful to American Independence

- David Bromwich(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Belknap Press(Publisher)

The house of Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of Massachusetts, was sacked and his library burned. The peace of the colonies was broken by a summer of riots; and the Stamp Act was a dead letter by November. No-body could be found to enforce the law, and nullification spoke louder than any reply. The American War 191 Had this been an isolated measure, the crisis might have passed, but the Stamp Act was part of a strategy by Grenville to assert greater power in the western empire through control of the colonial trade. In the back-ground lay the Sugar Act, passed on April 5, 1764, which cut in half an older tax on molasses and set more rigorous conditions of enforcement in order to raise revenue. Smuggling of molasses was thereby discouraged, and the colonists saw a decrease in the profits on rum. In general, the bookkeeper’s sobriety of the Grenville strategy brought more resentment than cooperation, and yet his stand was firm—smuggling, writes P. J. Marshall, “was an almost obsessive concern of Grenville’s”—and an un-friendly watchfulness was pushed into areas of policy that had lain unat-tended. 1 By the Currency Act, passed on September 1, 1764, colonial bills were abolished, the reissue of existing currency prohibited, and the cur-rency of the colonies placed under the regulation of Parliament. The Quartering Act of 1765 required that British offi cers and soldiers be bil-leted and quartered in colonial barracks and public houses and, if their numbers ran over, that they be accommodated at inns, ale houses, livery stables, and other such civilian commercial establishments, their expenses of food and lodging to be paid by the colonies. Looked at in all its parts, from the point of view of British settlers under a new imposition from British rule, the imperial policy of Grenville could seem to present a comprehensive design with a long future. - Hon. Sir John William Fortescue(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Normanby Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER II — AMERICA – 1763-1774

Political Changes in England; George Grenville succeeds Bute — He determines to enforce the Acts of Trade and impose Stamp Duties on the American Colonies for Support of the British Garrison — The Institution of this Garrison a reasonable Measure — Grenville consults the American Colonies as to a voluntary Contribution from them towards Imperial Defence — Negotiations fail; the Stamp Act passed — Organised Agitation and Riot in Massachusetts — Rockingham’s Ministry replaces that of Grenville — Pitt’s reckless Encouragement of the Agitation — Repeal of the Stamp Act — Fall of Rockingham’s Ministry; Pitt, created Earl of Chatham, forms an Administration — His Failure to form an Alliance of the Northern Powers of Europe — His Incapacity to deal with the American Difficulty — Agitation and Hostility of the Americans against British Troops — Inconsistency and Insincerity of this Agitation — Charles Townsend carries a Measure to levy Duties in the American Colonies — Renewal of the Agitation; two Regiments sent to Boston — Traditions of Rebellion in Boston — The Troops placed at the Mercy of the Mob of Boston — Patience of the Troops exhausted; the “Boston Massacre”. — Resignation of Chatham and Grafton; Lord North becomes Chief Minister — He repeals all the Duties except that on Tea — Weak State of the Army — The Pay of the Men insufficient — National Danger owing to the Difficulty of Recruiting The Carib War in St. Vincent — Improvement of the Situation in America — Trouble revived by the Acts of Trade and Navigation — Agitation renewed in Massachusetts; the Committees of Correspondence — The landing of Tea in American Ports prevented — Coercive Measures against Massachusetts — The Quebec Act — Meeting of the American Congress at Philadelphia — Failure of Coercion at Boston owing to the Insufficiency of the Force — Rapid Advance of the Revolution in New England.

- eBook - PDF

Eighteenth-Century British Premiers

Walpole to the Younger Pitt

- D. Leonard(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Grenville considered alternative methods of raising money, but concluded that the levying of stamp duties, which had been in force in Britain since 1671, would be the most efficacious. It would be ‘the least exceptionable means of taxation’, he told the Commons in his budget speech on 9 March 1764, ‘because it requires few officers and even collects itself’ (Lawson, 1984, p.200). Under the proposal, which met little opposition in the Commons, stamp duty would be imposed on all colonial commercial and legal papers, newspapers, pamphlets, cards, almanacs and dice. Grenville allowed for a year’s delay in applying the Act, in order that the views of the colonists on the actual implementation could be heard, but he did not at all anticipate the barrage of complaints that soon materialized. Indeed, he believed that his Act was an extremely moderate measure, calculated to raise only one-third of the cost of the British garrison, whereas many MPs felt that the colonists should contribute the full amount. Grenville had lost office by the time that the effects of the American boycott of the Act were felt, and the new Rockingham administration hastened 106 Eighteenth-Century British Premiers to repeal it (See Chapter 8). But the damage had been done, and the cry of ‘No taxation without representation’ was heard throughout the length and breadth of the 13 colonies. None of Grenville’s four succes- sors over the next decade were able or willing to accept the full con- sequences of the new American militancy, and it was probably only a matter of time before open conflict broke out between the colonists and their ‘motherland’. Grenville was supreme in the Commons, but his relations with the King continued to deteriorate, exacerbated by Grenville’s stubborn insistence on controlling official appointments, even those – like Keeper of the Privy Purse – which had previously been regarded as personal appointments by the monarch. - eBook - PDF

- Maria Montoya, Laura Belmonte, Carl J. Guarneri, Steven Hackel(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

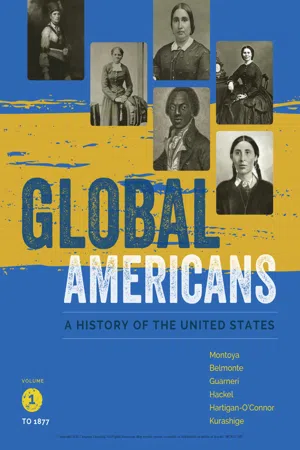

▲ Table 6.1 The Escalating Crisis Between 1764 and 1774, the British government sought tighter economic and political control over its American colonies from Quebec south to the West Indies. People in the coastal mainland colonies responded with increasingly coordinated resistance. Twice, Britain had to back down, repealing the Stamp Act and most of the Townshend Duties. Act Provisions Reactions Sugar Act 1764 Reduced tax on molasses and added tax on sugar, coffee, calico, etc.; established vice-admiralty court Individual colonies petition for repeal Currency Act 1764 Outlawed colonial paper money Scattered protests; circulation of pamphlets Stamp Act 1765 Placed tax on printed materials to be purchased with specie Street protests; nonimportation movement; formation of Sons of Liberty; Stamp Act Congress; repealed in 1766 Declaratory Act 1766 Asserted Parliament’s authority to tax American colonies Scattered protests Townshend Acts 1767 Placed tax on imported paper, lead, glass, paint, tea; revenues to pay British administrators Nonconsumption movement; formation of Daughters of Liberty; repealed in 1770 except for tax on tea Tea Act 1773 Permitted East India Company to sell tea in colonies with lower tax Protests dumping and confiscating tea Coercive (Intolerable) Acts 1774 Closed Boston port, cut powers of Massachusetts elected officials, permitted troop quartering in private buildings First Continental Congress, 1774 Quebec Act 1774 Acknowledged large British colony with protected Catholicism and French civil law First Continental Congress, 1774 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division [Robert Sayer and John Bennett/LC-DIG-ppmsca-19468] Copyright 2018 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. WCN 02-300 167 6-3 FROM RESISTANCE TO REVOLUTION from a standing army imposed with-out consent. - eBook - ePub

Routledge Library of British Political History

Volume 1: Labour and Radical Politics 1762-1937

- S. Maccoby(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

“The advices received from America”, it writes, “are full of the bad effects of the late act of parliament for regulating the trade of the plantations, and for laying a duty on their exports and imports, in order to defray the expences of their own government. The prohibitions laid upon their trade by this act, are grievously complained of, and the rigour with which these prohibitions are enforced by the men of war stationed on their coasts for that purpose, are by no means relished by the Americans, who subsist in a manner by their clandestine commerce with the French and Spaniards, and which must be connived at, if any advantage is to be expected from them by their mother country. On the other hand, the West Indians complain of this indulgence, and are preparing memorials to be presented to parliament, to put a stop to the North American distilleries, from French materials.”In face of this discontent and the protests that came in later from Colonial Assemblies both against the Act of 1764 and the further Stamp legislation he had proposed, Grenville resolved to go on unmoved.2 In February he brought forward a Stamp Bill, and in March it was placed on the Statute Book without serious opposition.3 Just when one American pamphleteer, who contrived to reach British ears, was affecting to look forward hopefully to the withdrawal of British troops and the end of the justification that had been suggested for the port-duties of 1764,1 the unprecedented Stamp taxes of 1765 were being imposed, the first ever ordered by Westminster to be collected beyond the harbours and inside the Colonies.It must, of course, be assumed that Grenville completely misjudged the explosiveness of the American situation and was probably unaware that he was facing anything more serious than the inevitable grumbling of a favourably placed class of taxpayers, asked at length to assume the full weight of their proper burdens. Such grumbling was apparently being overcome in the case of the Cider Counties and, on any Whitehall estimate, American grumbling could hardly cause greater trouble. Grenville, moreover, could not have given the American situation more than a fraction of his attention, for in the opening months of 1765 much else of seemingly greater urgency pressed upon him. Minority pamphleteering against the Government’s boastful financial claims was not yet ended;2 the reassembly of Parliament permitted the planning of more troublesome Minority manceuvre on General Warrants and the Seizure of Papers;3 and, weightier possibly than all else, was the problem of the King’s physical and mental condition. Only two days after he had opened Parliament on January 10, 1765 the King was seized with an alarming illness that brought some mental trouble and was hardly fully surmounted before the beginning of April.1 No Regency provision had yet been made to meet the possibility of a Royal demise though the heir was an infant not three years old, while the constitutional problems opened up by the similar lack of provision for a Royal incapacity of any duration were even more intricate. If the Court, in fact, endeavoured to conceal from Grenville the full extent of the King’s mental troubles,2 - eBook - PDF

Revolution Against Empire

Taxes, Politics, and the Origins of American Independence

- Justin du Rivage(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

142 t h e r i s e an d fa l l o f t h e s ta m p ac t the laws by constraint, and by open rebellion of the colonists, can’t be wished off by the power of any words whatsoever.” 124 Yet despite these complaints, the Declaratory Act was a powerful political weapon. By asserting the supremacy of Parliament over the colonies, a supremacy few in either America or Britain denied, the act gave wavering members of Parliament a way of rejecting both American rioting and the failures of authoritarian reform. Despite the “many ill natured things flung out against America,” by February 1766 the Rockingham ministry’s efforts were rapidly turning Parliament against the Stamp Act. Grenville ’s motion to enforce his tax went down by a two to one margin. Grateful merchants and the colonial agents crammed the lobby of the House of Commons, and the ministry delayed the mail packet ships bound for the colonies to relay the exciting news of the Stamp Act’s repeal. 125 For a majority in Parliament, the combination of government support, popular activism, and the threat of losing a great part of the empire was enough to convince them that the status quo antebellum was far preferable to the Grenville administration’s ambitious efforts to remake the empire. Finally, on March 4 , 1766 , the Stamp Act’s repeal passed the House of Commons, 250 to 122 . Passage in the House of Lords was more difficult, requiring Rockingham to convince the king of “how strong the torrent of opinion in favor of the repeal was.” 126 Yet, with George III’s blessing, thirteen days later the House of Lords ended the Stamp Act without a division. - eBook - ePub

George III

King and politicians 1760–1770

- Peter Thomas(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

The ministry, however, came to regard the Stamp Act as of great significance, because of the American response to Grenville’s announcement. Far from taking up his offer to suggest alternative modes of Parliamentary taxation, the colonies protested against that whole concept. 61 The Grenville ministry perceived the challenge to Parliamentary sovereignty. After a Treasury Board meeting in December 1764 James Harris made this note: ‘colonies would reject all taxes of ours, both internal and external – would be represented’. 62 By early 1765 the assertion of Parliamentary sovereignty over America had become for the ministry more important than the prospective revenue. That, in the final draft of the Stamp Bill, would be derived from stamp duties on newspapers, most legal documents, cargo lists for ships, and numerous other less recurrent items like liquor licenses, calendars, cards and dice. The chief burden would fall on printers, lawyers, merchants, and publicans. It was expected to yield £100,000, and, even with £50,000 from the molasses duty, American taxes would bring in less than half the £350,000 now estimated as the cost of the American army. 63 Parliamentary discussion of the subject began on 6 February, when Grenville introduced the appropriate resolutions after a carefully constructed speech. The colonial claim to be taxed only by their own representative bodies would apply equally to all other legislation, he said. The colonies were subject to the mother country, and none had been given exemption, by charter or otherwise, from Parliamentary taxation. All taxes were unpopular, like the one on cider, and fairness demanded that everybody should contribute, including the colonists, who were defended by Britain’s army and navy. The stamp duties would be efficient and equitably spread, and the colonists had not responded to the invitation to make alternative suggestions - eBook - PDF

George III

An Essay in Monarchy

- G. Ditchfield(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

52 But he had thoroughly approved of the principle of the Stamp Act in that year. It was mainly his dislike for Grenville, which was not eased by the latter's move to opposition after 1765, that led him in February 1767 to express a critical view of the manner of the Act's introduction. Scorning Grenville's predicted sup- port for a reduction in the land tax, against the wishes of the ministry, George III wrote to Grafton, with whom he was then upon very friendly terms: Mr Greenville's [sic] conduct is on this occasion as abundant in absurdities as in the affair of the Stamp Act; for there he first deprived the Americans by restraining their Trade, from the means of acquir- ing Wealth, & Taxed them, now he objects to the Public's availing itself of the only adequate means of restoring its Finances. 53 This was the wisdom of hindsight. It seems a shade fanciful to suggest that one reason why the King was determined never to employ Grenville again was a royal anxiety to promote harmonious relations with the colonies. 54 George III made no objection in 1767 either to the Revenue Act, which imposed the Townshend duties on the import of tea, paper, glass and lead to the colonies, nor to its purpose of raising a revenue in America to provide financial support for the governors and their admin- istrations which would render them financially independent of the colonial assemblies. Much later he was to describe his consent to the repeal of the Stamp Act as a major mistake. 55 During the divided ministries of Chatham and Grafton, the King's role in the endorsement of, or qualifications to, proposals of policy took on an added importance. In May 1767 he supported his ministers when the opposition in the House of Lords sought to push the administration into a firmer line over its response to the Massachusetts Assembly's amnesty for those involved in the agitation against the Stamp Act. - Paul Frame(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- University of Wales Press(Publisher)

This came in the form of the Declaratory Act, emphatically declaring Parliament’s right to legislate for the colonies ‘in all cases whatsoever’. 4 As a result parliamentary opposition largely evaporated and on the day that the Declaratory Act passed into law the Stamp Act was repealed. In America a degree of normality returned and a colonial boycott of goods imported from Britain ended shortly afterwards. In July 1766 the British government changed again when the king dismissed Rockingham and persuaded the elder Pitt to form an administration. This also brought into Government the earl of Shelburne who became Southern Secretary, a post that bore responsibility for the American colonies at this time but not in financial matters, which remained the prerogative of the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Charles Townshend. Rather surprisingly in view of colonial reaction to the Stamp Act, Townshend now returned to a policy of reasserting Parliament’s supremacy in colonial matters via yet another doomed flirtation with colonial taxation. The Townshend Duties, as the new taxes quickly became known, were to be imposed on such imported goods as tea, paint, paper, glass and china. Although initially devised to fund the army in America, their purpose later changed to one of helping to offset the cost of government in the colonies, by paying the salaries of colonial governors, judges and other officials. This the colonists saw as an attempt by the Westminster government to undermine the traditional responsibilities of their own state assemblies, making them ever more reliant on Britain and setting another new and dangerous precedent. Townshend did not live to see the consequences of his duties for he died on 4 September. Lord North, who succeeded him as Chancellor, at first enjoyed a period of relative quiet in the colonies, where opposition to the ON A PERILOUS EDGE 97 new duties developed only slowly.- eBook - PDF

- P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, Sylvie Waskiewicz(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

Figure 5.13 Lord North, seen here in Portrait of Frederick North, Lord North (1773–1774), painted by Nathaniel Dance, was prime minister at the time of the destruction of the tea and insisted that Massachusetts make good on the loss. In early 1774, leaders in Parliament responded with a set of four measures designed to punish Massachusetts, commonly known at the Coercive Acts. The Boston Port Bill shut down Boston Harbor until the East India Company was repaid. The Massachusetts Government Act placed the colonial government under the direct control of crown officials and made traditional town meetings subject to the governor’s approval. The Administration of Justice Act allowed the royal governor to unilaterally move any trial of a crown officer out of Massachusetts, a change designed to prevent hostile Massachusetts juries from deciding these cases. This act was especially infuriating to John Adams and others who emphasized the time-honored rule of law. They saw this part of the Coercive Acts as striking at the heart of fair and equitable justice. Finally, the Quartering Act encompassed all the colonies and allowed British troops to be housed in occupied buildings. At the same time, Parliament also passed the Quebec Act, which expanded the boundaries of Quebec westward and extended religious tolerance to Roman Catholics in the province. For many Protestant colonists, especially Congregationalists in New England, this forced tolerance of Catholicism was the most objectionable provision of the act. Additionally, expanding the boundaries of Quebec raised troubling questions for many colonists who eyed the West, hoping to expand the boundaries of their provinces. The Quebec Act appeared gratuitous, a slap in the face to colonists already angered by the Coercive Acts. American Patriots renamed the Coercive and Quebec measures the Intolerable Acts. - eBook - PDF

The Brief American Pageant

A History of the Republic

- David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl, , David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

While flags flapped at half-mast, the law was openly and flagrantly defied—or rather, nullified. Britain was hard hit. Merchants, manufacturers, and shippers suffered from the colo-nial nonimportation agreements, and hundreds of laborers were thrown out of work. Loud demands converged on Parliament for repeal of the Stamp Act. But many of the members could not understand why 7.5 million Britons had to pay heavy taxes to protect the colonies, whereas some 2 million colonists refused to pay for only one-third of the cost of their own defense. After a stormy debate, Parliament, in 1766, grudgingly repealed the Stamp Act. But in virtually the same breath, it provocatively passed the Declaratory Act , reaffirming Par-liament’s right “to bind” the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” The British government thereby drew its line in the sand. It defined the constitutional principle it would not yield: absolute and unqualified sovereignty over its North American colonies. The colonists had already drawn their own battle line by making it clear that they wanted a measure of sovereignty of their own and they would undertake drastic action to secure it. The stage was set for a continuing confrontation. The Townshend Tea Tax and the Boston “Massacre” Control of the British ministry was now seized by the gifted but erratic Charles (“Cham-pagne Charley”) Townshend, a man who could deliver brilliant speeches in Parliament even while drunk. Rashly promising to pluck feathers from the colonial goose with a minimum of squawking, he persuaded Parliament in 1767 to pass the Townshend Acts . The most important of these new regulations was a light import duty on glass, white lead, paper, paint, and tea. Townshend made this tax, unlike the Stamp Act, an indirect customs duty payable at American ports. Flushed with their recent victory over the stamp tax, the colonists were in a rebellious mood. - eBook - ePub

Narrative and Critical History of America, Vol. 6 (of 8)

The United States of North America, Part I

- Justin Winsor, (Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The difficulty arose from a misconception of the relations of the colonies to the mother country. They were not a part of the realm, and could neither equally share its privileges nor justly bear its burdens. The attempt to bring them within imperial legislation failed, and could only fail. They were colonies; and the chief benefit the parent state could legitimately derive from them was the trade which would flow naturally to Great Britain by reason of the political connection, and would increase with the prosperity of the colonies.Early in 1763 the Bute ministry, of which George Grenville and Charles Townshend were members, entered upon the new policy. To enforce the navigation laws, armed cutters cruised about the British coast and along the American shores; their officers, for the first time, and much to their disgust, being required to act as revenue officers. To give unity to their efforts, an admiral was stationed on the coast. To adjudicate upon seizures of contraband goods, and other offences against the revenue, a vice-admiralty court, with enlarged jurisdiction, and sitting without juries, was set up.[45] Royal governors, hitherto chiefly occupied with domestic administration, were now obliged to watch the commerce of an empire. It was seen long before this time that the successful administration of the new system would require some modification of the provincial charters; but the difficulties were so serious that the matter was deferred.Such was the new order of things. The student who reflects upon the complete and radical change effected or threatened by these new measures, so much at variance with the habits and customary rights of the colonists, breaking up without notice not only illicit but legitimate trade, and sweeping away their commercial prosperity, is no longer at loss to account for the outburst of wrath which followed the Stamp Act, a year later.[46]

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.