History

Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo was a powerful state located in west-central Africa during the 14th to 19th centuries. It was known for its sophisticated political structure, trade networks, and the early adoption of Christianity. The kingdom's economy was based on agriculture, mining, and trade, and it played a significant role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

9 Key excerpts on "Kingdom of Kongo"

- eBook - ePub

- John Parker(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

6 Yet Kongo’s wealth of written and oral sources have raised complex problems of interpretation, for example as its historians have sought to understand and to reach beyond Afonso’s efforts to recast the past and to shape the future. How and what can we know, then, of the kingdom over which Afonso and his brother fought in 1506?KONGO BEFORE 1500

The origins and early history of Kongo have been the subject of much debate. One point of contention has been the narrative of Lukeni lua Nimi’s founding of the kingdom, a process that historians tend to date to some point in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. This is a debate that extends beyond the region and even beyond Africa, as at its core is the issue of the relationship between ‘myth’ and ‘history’. Kongo was one of many Bantu-speaking kingdoms in Central Africa of which the traditions of origin turned on the arrival of a noble stranger from across a river, who seizes power from an older, often despotic, dynasty and inaugurates a new civilized social order based on sacred kingship. Vansina’s pioneering efforts to mobilize these accounts tended to take them quite literally, assuming that culture heroes like Lukeni lua Nimi, Kalala Ilunga of the Luba and Cibinda Ilunga of the Lunda were historic state-builders whose conquests could be dated by counting the generations of remembered kings back from verifiable successors.7 Subsequent interpretations, however, rejected the idea that these were historical figures. The anthropologist Luc de Heusch, most prominently, argued that traditions of origin were mythical charters, albeit ones with profound and deeply rooted meanings for local societies.8 - eBook - ePub

Angola

Struggle For Peace And Reconstruction

- Inge Tvedten(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The last step in this political development was the creation of kingdoms. A kingdom was more complex than a chiefdom in that the ideology of authority was more developed and territorial organization, through structures of chiefs and subchiefs, was larger. In Angola, there were many kingdoms of different sizes, of which the most important was the Kongo kingdom (Hilton 1985). According to traditional history, the Kongo state was established by the son of a chief from the area of present-day Boma in Zaïre in the fourteenth century, who moved south of the Zaïre River into northern Angola and established M’banza Congo as his base. One reason for his success in conquering other peoples and chiefdoms was his strategy of absorbing the population into Kongo political and economic structures rather than trying to remain their overlords. The economic basis for the maintenance of the kingdom as a political structure was the collection of taxes and the extraction of tribute in the form of labor on royal land. The king also eventually monopolized ownership of the shells found in the royal fishery, used as the means of exchange. By the middle of the fifteenth century, the Kongo king ruled over large parts of northern Angola and the northern bank of the Zaïre River, and by the early sixteenth century (i.e., at the beginning of the colonial period), the kingdom was large enough to be divided into six provinces under separate subchiefs. It covered over one-eighth of present-day Angola.Other important kingdoms were the Loango kingdom of the Vili, in presentday Cabinda; the Mbundu kingdom of Ndongo, located to the south of Kongo; Matamba and Kasanje, located east of Ndonga; and Lunda, which was east of Matamba and was later to be heavily infiltrated by the Luba of central Katanga and later still absorbed by the Chokwe. The Ovimbundu, who today constitute the largest ethnolinguistic group in Angola, moved into Angola in waves between 1400 and 1600 but were never consolidated as one kingdom. Rather, they consisted of some twenty-two individual entities, of which around thirteen emerged as coherent and strong political units. Of these, the Bié, Bailundu, and Ciyaka were the most important. Finally, the Kwanyama established a strong kingdom near what is now the border between Angola and Namibia. In all these kingdoms, a three-tier social structure of commoners, and slaves developed.8Thus, the kingdoms largely coincided with the main ethnolinguistic groups. The economic power and influence of the kingdoms were later enhanced with the coming of the Portuguese, particularly through the slave trade, and through this process, the kingdoms also came into more frequent contact with each other. The increased importance of the accumulation of wealth would, however, also initiate degeneration among these same kingdoms as their religious and cultural bases were undermined.Angola Under the Portuguese

For most of the Portuguese colonial period of nearly 500 years, Portugal exerted only tenuous control over Angola. Northern Angola was not formally part of the colony until 1880 and was not really controlled before 1920; the Portuguese colonial authorities did not thoroughly penetrate the heavily populated areas of the high plateau until the end of the nineteenth century, and they never developed any coherent system of rule similar to that of the French or the English in their colonies. In fact, for most of the colonial period, their presence was restricted to a few ports along the Angolan coast. As late as 1845, there were only around 2,000 Portuguese in the colony, and the number had risen to only 40,000 by 1940. The main influx of Portuguese, who numbered around 340,000 at the time of independence in 1975, took place during the last twenty years of the colonial era. - eBook - ePub

Real Lives in the Sixteenth Century

A Global Perspective

- Rebecca Ard Boone(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

From 1506 to 1543 Afonso I ruled Kongo, one of the most powerful kingdoms of its time in Africa. Inspired and strengthened by Portuguese churchmen and soldiers, he made Christianity the state religion throughout his domains. Remembered by some as the “Apostle of the Kongo,” Afonso blended Catholicism with elements of African religion to establish Kongo as a powerful Christian kingdom. His openness to aspects of a new and radically different culture combined with a sophisticated understanding of how to preserve the interests of his people allowed this African king to modernize his lands on his own terms. His political and religious legacy impacted millions of Africans dispersed throughout the Americas during the years of the Atlantic slave trade.The origins of the Kingdom of Kongo

The domains of the sixteenth-century Kingdom of Kongo now lie divided between present day Angola, The Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo in Central West Africa. An enormous continent, Africa is large enough to hold the entire United States, China, and most of Europe within its land mass. Throughout its long history, Africa had seen the rise and fall of numerous kingdoms and empires. In the far north and northeast, the states of Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Sudan boasted cities that belonged to the cultures of classical antiquity. By 700 CE, the peoples of these regions had converted to Islam and were integrated into growing Islamic empires. South of the Sahara, camel caravans full of luxury goods began to make their way across the desert to the West African states of Mali and Benin around 1000 CE. Another empire, Zimbabwe, flourished in Central East Africa in the fourteenth century. Nearly two thousand miles from any other African kingdom or empire, the Kongo had little if any contact with other states and developed independently.Figure 3.1 Olfert Dapper, Alvaro I of Kongo receiving the Dutch ambassadors, 1668. No contemporary image of Afonso I survives. This seventeenth-century woodcut portrays his grandson and heir, Alvaro I.Source: Private collection/Bridgeman ImagesThe people of Kongo spoke Kikongo, one of around 500 Bantu languages spoken south of the Equator in Africa. Over the course of millennia, the people of this language group had come from the northwest to form settlements in the savannah region below the Congo River. Skilled in agriculture and ironworking, the ancestors of the Kongolese people grew prosperous by controlling trade between the coastal, plateau, and forest areas in the region. By 1350, six independent states had united to form the Kingdom of Kongo. - eBook - ePub

Blacksmiths of Ilamba

A Social History of Labor at the Nova Oeiras Iron Foundry (Angola, 18th Century)

- Crislayne Alfagali(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Oldenbourg(Publisher)

6 In Map 1, these divisions are clearer. It was published in Paris in 1764, and was drawn by Jacques Nicolas Bellin, an important cartographer from the French Navy.Map 1: Map of the Kingdoms of Loango, Kongo, Angola, and Benguela, 1764.Source: Jacques Nicolas Bellin, “Carte des Royaumes de Congo, Angola et Benguela avec les pays Voisins, Tire de l’Anglois,” 1764, National Maritime Museum, Paris, available athttp://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~233286~5509680:Carte-des-Royaumes-de-Congo,-Angola?sort=Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No?&qvq=q:angola;sort:Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=16&trs=25, accessed July 1, 2016.In this map, the rivers that cut through the territory are highlighted: the Zaire River as a natural border between the Kingdom of Loango and the Kingdom of Kongo; the Kwanza River, the main waterway of the Kingdom of Angola; the Kunene River in Benguela, which until the late-eighteenth century marked the limits of the territory to the south of Angola known to the Portuguese—the lands beyond the Kunene River were unexplored territory.Given the precarious nature of the Portuguese presence in African territory, many historians consider that it is erroneous to call the Kingdom of Angola a colony, or even to call colonial times the period of Portuguese occupation from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The first endeavors of Portuguese expansion are seen by these authors as attempts at colonial administration, especially after the appointment of the Governor General Francisco d’Almeida in 1592. For some, it was only after 1915, with a population of 20,000 white people, that a colonial administration was possible, with a fiscal administration only in place in the 1950s.7 - eBook - ePub

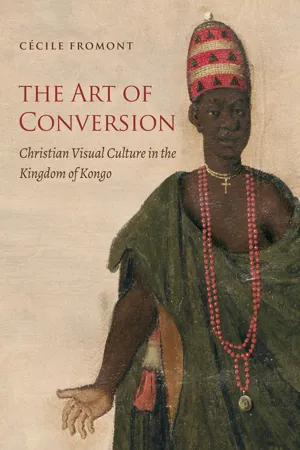

The Art of Conversion

Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo

- Cécile Fromont(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Omohundro Institute and UNC Press(Publisher)

The idea of fetishism, which would eventually become the prominent European descriptive and analytical term for African culture in the nineteenth century, encapsulated the perceived inability of the inhabitants of the region to produce elaborate forms of social organization, conduct rational economic transactions, or develop sophisticated religions. If European accounts of the Kongo could be very stark and critical, the objections they raised were not those encompassed by the newly developed term fetishism. Far from these prejudiced views, the numerous descriptions of the Kongo as an eminent realm of ancient wisdom testify to the success of Afonso’s cross-cultural invention. 25 Iron Kingdom and Iron King The Kongo Christian discourse that Afonso created functioned equally well in both European and African contexts owing in large part to the two visual and symbolic hinges that anchored it: the motif of iron and the image of the cross. Kongo myths of creation recorded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries associated the foundation of the kingdom with the arrival of a civilizing hero and founding king who brought with him knowledge of iron technology. Since ironworking had been practiced in the region for at least several centuries before the emergence of the kingdom, the association was not grounded in historical fact; rather, it reflected the fundamental significance of the link between kingship and the metal in the political worldview that the myths expressed. The mythical and ritual pairing of iron and leadership is a shared feature of many central African polities both in the past as well as in recent times. Twentieth-century Bakongo consultants from the region that once formed the core of the Kongo kingdom expressed the connection with the term ngangula a kongo, or “smith of the Kongo,” which they used as a royal title - eBook - ePub

The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa

Fighting Their Way Home

- Erik Kennes, Miles Larmer(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Indiana University Press(Publisher)

made the state structures in Katanga—made it possible to practically envisage an independent Katanga, created the conditions for hostility toward Kasaian labor migration, and yet placed identifiable limits on the ultimate success of the secessionist project. While Katanga’s alliance with Belgian advisers and capital had the effect of preserving Katanga’s comparatively developed infrastructure development—and, ironically, making possible subsequent Zairianization measures—the practical impact of colonialism on Katanga made it impossible to effectively integrate the territory’s diverse population into a cohesive national project.“Katanga” before the Congo Free State

The social and political formations present in the area of central Africa that ultimately formed Katanga had for centuries been significantly shaped by their trade-based interactions with the wider world. Metalworking, in iron but also in copper, was central to the growing economies of the region. The area around Lake Kisale was an important center for metalworking, and its prosperous inhabitants produced a food surplus, including dried fish, which they traded for, among other goods, copper mined to the south in the modern Copperbelt. In the fourteenth century a centralized kingdom, under the Kongolo dynasty, developed among a people known as the Luba. The origins of the Luba political aristocracy can be traced back to three clans: one Songye, one Kanyoka, and one Lunda. The oral tradition clearly refers to a link between the Lunda and the Luba: around 1400, the female ruler of the Lunda, the Lueji/Ruej, married Tshibinda Ilunga/Cibind Irung, a member of the Luba aristocracy. Luba political principles were incorporated into the Lunda political system, thereby creating an element of unity between what was later southern and northern Katanga.4Several waves of westerly out-migration from the core Luba area (located, according to oral tradition, in a place called Nsanga a Lubangu) took place during the early stages of Luba consolidation, commonly associated with intra-aristocratic conflict and the need to address population concentration at a time of famine, probably around the fifteenth century. This led to the distinction between the Luba Katanga (or Lubakat, also known as Luba Shankadi, probably meaning “faithful”) and the Luba Lubilanji in Kasai, a distinction which became increasingly rigid in the subsequent period and which has direct relevance for this history.5 - eBook - ePub

How Societies Are Born

Governance in West Central Africa before 1600

- Jan Vansina(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of Virginia Press(Publisher)

Its name is a straightforward derivation from *- kóda “to become strong.” 96 Local oral traditions associate it with the rise of the Kingdom of Ndongo and imply that it is as old as that kingdom was, i.e., the late fifteenth century. The kings of Ndongo were called ngola, after the charm, and the Portuguese derived Angola from the title. The ngola 9/10 was a piece of iron, in the shape of a hammer, a bell, a hoe, or a knife, kept in a shrine with a guardian, as is still the case among the Holo. 97 Once invented, this charm was adopted not just in Ndongo but spread far into the western corridor southwest of the Cuanza basin, as well as on the planalto, and even as far as Huila. 98 Here, as on the planalto, the essential glue holding principalities or kingdoms together was the notion of a common ruler rendered concrete in the shape of a person. The existence of a ruler created the consciousness among the subjects of belonging to a common realm. 99 The larger the realm, the more exalted the king had to be. Thus the Portuguese considered the ruler of Ndongo to be a divine king, for did not the inhabitants of the realm declare that what God was to the Portuguese, their king was to them? 100 And the idea that their king was imbued with the highest supernatural spirit remained common even after a century of Christianization. It was the ruler who was held responsible for the very life of his subjects through his or her power over rain and all forms of fertility, and government consisted in managing the supernatural in such a way that prosperity reigned. Rulers rarely appeared in public, but when they did, it usually was to be shown to promote fertility and prosperity. They solemnly presided over sowing and first-fruit rituals, they initiated the rituals to obtain rain, to end an epidemic, and they declared war. In these essentially spiritual tasks, the most exalted rulers, such as those of Ndongo, were assisted by a special group of diviners, the shingila 1n/2 - Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba, Toyin Falola, Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba, Toyin Falola(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

48The Luba kingdom of West Central Africa had emerged by about 1500, and according to oral traditions achieved its political structure during the reign of Kalala Ilungu who overthrew his uncle, the purported founding king Kongolo. The Luba king held absolute authority over subordinate chiefs and titleholders. The basic administrative structure of the kingdom was hierarchical and rested on lineage -based homesteads, villages under headmen, chiefdoms each under a territorial chief (kilolo ), and provinces. The central government comprised the king and titleholders; territorial and provincial chiefs had titles, as did counselors and officials at the capital, such as the war leader, the head of the officer corps , and the keeper of the sacred emblems. Usually titleholders were relatives of the king, and when the king died they were replaced by relatives of the new king . The only legitimate claimants to the kingship were those who were believed to have a sacred quality, bulopwe , believed to be vested in the blood and transmissible only through males. Bulopwe gave kings the right and the supernatural means to rule; all bulopwe stemmed from Kongolo or Kalala Ilunga, hence the king ruled by divine right and had supernatural powers, and challenges to the king could only come from other descendants from these two rulers . The organization of the kingdom was perpetuated by two devices: perpetual succession and positional kinship. Each successor to any given office took the title and name of the original holder of the office, hence all rulers had the same name even though they were not necessarily father and son; anyone who took over a position also took the earlier titleholder’s name, even if they were unrelated. If the original titleholder was a relative of another titleholder, then that relationship between the two positions became permanent in a fictitious relationship. The relations between different offices were made permanent based on fictional, positional kinship. Earth priests were usually the head of the original family lineage which founded their village, and because of this connection with the ancestral founders they had highly respected religious powers. The priests had the authority to regulate land use and they allocated land for settlement indirectly by supervising lineage heads, who regulated access to hunting land , fishing streams, and fruit trees in the forest. Sometimes the priests took on direct political roles of leadership; usually, however, they worked with a chief who needed the earth priest’s approval in order to have legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The chief would recognize the powers of the earth priest through gifts and tribute , and political rituals such as the investiture of a new chief involved sacred symbols and the participation of the priest.49- eBook - ePub

Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition

Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives

- Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.(Publisher)

Maroon communities in both Palmares in Brazil and Limón in Colombia conducted wars of resistance against the Portuguese, Dutch, and Spanish that resembled Njinga’s wars against the Portuguese in Angola.Njinga was the head of an independent African kingdom with its own army and the ability to engage in diplomacy, wage wars, or do business with Europeans. The states she ruled—Ndongo and later Matamba—had subjects loyal to her but also contained various groups of dependents, some of whom were slaves. Njinga was an independent monarch fighting to uphold her right to be the queen of Ndongo. Most of the peoples of African descent in the Ibero-Atlantic world never found ways to sustain years of wars against Europeans or live in autonomous communities.In order to interpret Njinga’s engagement with European writing as an instrument of negotiation, one needs familiarity with the history of European literacy in Central Africa. Exposure to Catholic Christianity and Portuguese customs made rulers like Njinga more familiar with European forms of governance and lifestyle than their counterparts in other areas of Atlantic Africa, whose states supplied slaves to the Portuguese or with whom they conducted diplomatic relations. The earliest European-style school for Kongos was established in 1491 by a literate member of the Kongo elite who had returned to the kingdom with the first Portuguese cultural mission.From 1491 onward, the Kongo elite had access to European-style education. In 1625, for example, Jesuits in the capital of Kongo, São Salvador, had established a college for children of the Kongo nobility. Literate Kongos went as ambassadors to Portugal, the Vatican, the Portuguese in the Kingdom of Angola, and Njinga’s court. Furthermore, some Kimbundus who had been integrated into Portuguese Angola were also educated by Jesuit missionaries in Luanda, and many joined Njinga’s cause.

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.