History

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was a U.S. initiative to aid Western Europe's economic recovery after World War II. Proposed by Secretary of State George Marshall in 1947, it provided financial assistance to help rebuild war-torn countries, stabilize their economies, and prevent the spread of communism. The plan was instrumental in fostering post-war reconstruction and fostering economic cooperation among European nations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Marshall Plan"

- eBook - ePub

The Marshall Plan Today

Model and Metaphor

- John Agnew, J. Nicholas Entrikin(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In particular, the spirit of integration represented by the European Union can be traced to the immediate postwar years when a group of western European political leaders, such as Monnet, Schuman, De Gasperi, and Adenauer, combined a vision of an integrating Europe with support for an American plan of economic recovery and institutional reform. This initiative was directed as much at preventing a recurrence of the Depression of the 1930s as at minimizing the likelihood of a return of the national animosities that had produced the two world wars. As such it closely matched contemporary American imperatives. Along with the military commitments of the United States to western Europe in the form of NATO, designed to frustrate Soviet ambitions beyond the sphere of influence agreed to by the Allies (the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union) at the Yalta conference in 1945, the most important material and symbolic economic commitment of the US government took the form of the Marshall Plan, designed to limit the political success of indigenous Communist parties by pointing to American financial support and the absence of any Soviet equivalent, stimulating European economic growth to help American exports, and creating (in conjunction with the Bretton Woods Agreement on currencies of 1944) a world economy in which the competitive protectionism of the 1930s would be a thing of the past.The Marshall Plan has become the centerpiece of claims about what distinguished the aftermath of World War II in Europe from that of World War I, particularly the limited emphasis on reparations from a ‘guilty’ Germany and the necessary role in this played by the United States government, and the specific American contribution to western European economic growth and prosperity in the 1950s and 1960s. It has also become a model or rhetorical device for exhorting planned external intervention elsewhere, more recently for eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, and most recently for Afghanistan and Iraq, to do what the Marshall Plan is alleged to have done so successfully for western Europe after World War II. More than fifty years after the introduction of the Marshall Plan, therefore, the plan still lives on but now as a model for organizing the transition from state socialism to open market economies. As Barry Eichengreen (2001, 141) has noted, the Marshall Plan was a unique response to a particular historical circumstance, but ‘Marshall’s key insight, that a market economy needs institutional and policy support to function effectively, is as timely today as 50 years ago.’ - eBook - PDF

Manipulating Hegemony

State Power, Labour and the Marshall Plan in Britain

- R. Vickers(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

2 The Marshall Plan 19 As so much has been written about the Marshall Plan, it is easy to lose sight of some of the basic events in its evolution. Because of this, this chapter places the Marshall Plan in its historical context, while consider- ing the purpose and significance of the Marshall Plan. It discusses the content of Marshall’s speech that launched the aid programme, and ana- lyzes the economic, political and strategic reasons for the Marshall Plan, arguing that it is helpful to see the Marshall Plan as the result of a multi- tude of foreign policy goals. It then goes on to describe in some detail the response of Western Europe and the Soviet Union to the Marshall Plan. The split between Western Europe and the Soviet Union over their atti- tudes towards Marshall Aid was to lay the foundations of the split within the left in Britain.The chapter then places the Marshall Plan in the frame- work of the developing cold war, and addresses the nature of the relation- ships between Britain and the US, and Britain and the Soviet Union. 2.1 Marshall’s speech George Marshall, who had played the crucial role of US Army Chief of Staff during the Second World War, was appointed Secretary of State on 21 January 1947. Having assessed the extent of the devastation in Europe, he went on to make his famous speech in which he outlined what came to be known as the Marshall Plan, or, more properly, the European Recovery Programme (ERP), at Harvard University on 5 June 1947. According to Marshall, the remedy to Europe’s problems lay in restoring the economic confidence of the European people. This was a necessity for the well-being of America as well as Europe, as, Aside from the demoralizing effect on the world at large and the possibilities of disturbances arising as a result of the desperation of R. Vickers, Manipulating Hegemony © Rhiannon M. Vickers 2000 the people concerned, the consequences to the economy of the United States should be apparent to all. - eBook - ePub

- Günter Bischof(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Studien Verlag(Publisher)

First of all, the “dollar gap” of the European balance-of-trade deficit had to be filled. In order to stimulate the European economy, the USA provided coal, cotton, food, fertilizer and machines. The economic exchange between town and country had to improve. The Americans made it a condition that the European nations should cooperate more closely in order to speed up the integration and recovery of their national economies, which would enable them to finance necessary imports in the future. The U.S. authorities were not interested in resolving emergency situations in different European countries any longer but stipulated definite conditions for a future economic cooperation. An additional motive for this concept was the decision to contain Communist influence in Europe.All these ideas inspired Marshall’s iconic address at Harvard on 5 June 1947, which is regarded as the starting point for the European Recovery Program.31 Marshall told the President of Harvard only on May 28 that he would attend the commencement and accept an honorary doctorate. He promised to make a few informal remarks “in appreciation of the honor and perhaps a little more.”32 The Marshall Plan, as it was to be called soon, had a lot of fathers in the USA.33The Europeans did not take long to respond to the Americans’ offer. The British and the French Foreign Ministers convened a European conference in Paris. Scheduled to take place in late June, the meeting provided an opportunity to consider the offer and to calculate the total European demand for economic aid. Molotov, the Soviet foreign minister, came to Paris because Marshall had emphasized that the Europe he had in mind “extended to the Urals.” Molotov banked on a form of economic aid that was not subject to any stipulations such as the Lend-Lease Program during World War II. Stalin’s conditions for the Soviet delegation were clear: Moscow insisted on national aid programs that would not limit the individual states’ sovereignty. Eastern Europe should not be considered as a mere supplier of raw materials for Western Europe. And the resources in Western Germany should not be touched before a reparation balance had been achieved that would grant the Soviet Union access to the Ruhr.Bevin and Bidault supported the Americans, who were not willing to accept shopping lists from the various European states. The European countries’ mutual trade with resources including German Ruhr coal was vital for the recovery of all of Europe. The U.S. authorities expected the disclosure of the national European budgets to calculate the amount of resources that would be needed, which Moscow regarded as an infringement on the countries’ national sovereignty. In truth, Stalin did not want to divulge the massive problems of the Soviet economy and reveal his government’s failings. In addition, the Soviet secret service had informed the Kremlin that secret consultations had taken place between the British and the French before the conference in Paris; these talks aimed at the recovery of Western Europe and an integration of Western Germany—and did not include any reparations for the Soviet Union.34 - eBook - ePub

Paul G. Hoffman

Architect of Foreign Aid

- Alan R. Raucher(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

5 TheMarshall Plan,1948-50Scholars have usually portrayed the Marshall Plan as a policy of enlightened national self-interest. Within the framework of the containment of Communism, the United States pursued peace and prosperity by unprecedented generosity toward potential economic competitors. During a period of domestic shortages and inflation, it gave the countries of Western Europe billions of dollars so that they could reconstruct their economies and reestablish normal trading patterns.Recently, some scholars have charged that the policies of the Economic Cooperation Administration differed significantly from its own rhetoric and the conventional view. According to one leading revisionist work, the ECA actually pursued a hidden agenda of shoring up American capitalism against a postwar depression. It defined successful economic recovery not by improvements in the living standard of the European masses but by the control of inflation and the narrowing of the dollar gap so that Americans could find markets for the surpluses they could not absorb domestically.1Much can be learned by looking beneath the surface of events and of the rhetoric churned out by the government’s publicity apparatus. However, the revisionist exposé compares the ECA with a standard to which the American policy-makers did not aspire. In a sense, revisionists have created a straw man of altruism and have then proved that reality fell short.For two and a half years, ending 30 September 1950, Paul Hoffman occupied a key position and made major contributions within the complex process of government policy-making. He liked to say that no man did another a greater favor than President Truman did for him by drafting him to head the Marshall Plan. “It opened my eyes to many things of which I was totally unaware,” he told one interviewer, “and it was the beginning of my real education.”2 - eBook - ePub

Harry S Truman: The Economics Of A Populist President

The Economics of a Populist President

- E Ray Canterbery(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

8 The Marshall PlanM uch was going on during the Campaign of 1948, including the laying of the groundwork for what would be called “The Marshall Plan.” Next, we focus on the forces that led to the Plan as well as re-visiting a famous speech. As already noted, Secretary of State George C. Marshall (1880–1959) was the key player, though there were others. Still, a good place to begin is with Marshall’s speech at Harvard in which he said, “Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine, but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a worldwide working economy promoting the survival of free institutions.” The Soviets and their Eastern European satellites were not to be to be excluded from the program but rather, were invited to participate. While the Communist bloc countries could opt out of the plan, the burden of dividing the continent would fall exclusively on them. In short, it was going to be virtually a global plan, with ripple effects throughout the world community.The goal was European self-sufficiency. The US had already provided $6 billion in postwar aid to Europe. The Marshall Plan was scheduled to cost $16.5 billion over four years, a huge amount of aid in 1947 dollars. Among the promises greatly expanded US-European trade, with a recovered Europe prosperous enough to finance purchases of American goods. The positive effect on the trade balance with its multiplier consequences was irresistible to Congress and to the country. It was a plan that would guard an unstable Western Europe from Communist subversion while also promoting the prosperity of both Europe and the United States.The speech was delivered at 2:00pm in Harvard Yard at a luncheon given for alumni, parents of alumni and select guests. No one at the time had anticipated its import. Marshall had told Harvard President James Conant that he would simply make a few remarks — and perhaps “a little more.” No one had seen the final draft of the speech, not even President Truman. It nonetheless was an address that would transform Europe, dramatically change the international political landscape, and launch America as a modem superpower with global reach. Of course, it was not simply the speech, but everything that had taken place before and after it that would be transforming. The “before” picture included the influence of Hoover’s reports. - Wilson D. Miscamble, C.S.C.(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER TWO Launching the Marshall PlanA CRISIS SITUATION ?Kennan's first major entry as director of the Policy Planning Staff into the arena of foreign policy formulation saw him contribute in an important manner to the development of what became known as the Marshall Plan. This Plan, known officially as the European Recovery Program (ERP), has long held an exalted place on the list of postwar American foreign policy achievements. The dramatic (and flattering) picture of a wholehearted and generous American effort reviving a dispirited and prostrate Europe was the staple of the early and somewhat hagiographic accounts of the Marshall Plan and lives on as evident in the celebratory comments of public figures at the time of its fortieth anniversary in 1987.1 Whatever its impact on Europe, unquestionably the Marshall Plan marked a turning point in American diplomacy. It injected the United States into the midst of European affairs and marked a level of peacetime involvement there notably greater than in any preceding period. But recent scholarship has raised questions about the necessity of this American involvement, its origins, and its real purposes.2 Illuminating Kennan's key participation in the making of the Marshall Plan affords the opportunity to address these questions and allows a richer appreciation for how the eventual policy emerged.Alan S. Milward, an economic historian at the London School of Economics, has sought to slaughter a sacred cow of conventional interpretations of the Marshall Plan by disputing the very reality of the situation that supposedly called it forth. After amassing assorted statistical evidence he argued that Europe was not on the verge of economic collapse in the spring and summer of 1947. For him "the alleged economic crisis of the summer of 1947 in Western Europe did not exist, except as a shortage of foreign exchange caused by the vigor of the European investment and production boom."3 His argument, while noteworthy for its originality, goes completely against the grain of what everyone thought at the time.4 Perhaps Theodore White, a reporter in Paris in 1947 and 1948, engaged in retrospective hyperbole in describing Europe as a bankrupt civilization—whose condition was "that of a beached whale that has somehow been stranded high beyond the normal tides and which, if not rescued, will die, stink and pollute everything around it."5 But such views, even if more soberly expressed, were widely shared on both sides of the Atlantic. The influential Walter Lippmann publicly called attention to Europe's plight in March and April but officials within Truman's administration hardly needed to be briefed by him.6 Secretary Marshall's sincerely held conclusions about Europe's dire prospects and the resultant opportunities they presented the Soviet Union were derived from his discussions in Moscow with Ernest Bevin and Georges Bidault and from reports from American representatives in Europe.7- eBook - ePub

The First Cold Warrior

Harry Truman, Containment, and the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism

- Elizabeth Edwards Spalding(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

To be sure, the ERP addressed the economic devastation that defined the early postwar period of the Cold War. But as Truman later explained, “the world now realizes that without the Marshall Plan it would have been difficult for western Europe to remain free from the tyranny of communism.” 37 Marshall connected the idea of recovery to containment. At Harvard, he said of the plan precisely what critics overlook: “Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist. . . . Furthermore, governments, political parties, or groups which seek to perpetuate human misery in order to profit therefrom politically or otherwise will encounter the opposition of the United States.” 38 According to the Truman Doctrine, as elaborated here by Marshall, free nations require a concomitant infrastructure of free institutions in order to prosper. Some have argued that the Marshall Plan constituted a New Deal for Western Europe. In terms of being a massive national response to an immediate and continuing economic crisis, this is correct. But in the Marshall Plan, the American government was not only investing outside its borders in an economically devastated Western Europe but also acting within the extraordinary—and ongoing—circumstances of the Cold War. There were always clear objectives, in terms of goals and time, to the program. Priming the pump through the ERP meant using every possible opportunity for aid, but concentrating it at points where it would cause immediate recovery, with the final aim of establishing a self-sufficient European economy. And as Truman had stressed at Baylor University, the European Recovery Program would not be simply a series of government programs: “Freedom has flourished where power has been dispersed - eBook - ePub

Lincoln Gordon

Architect of Cold War Foreign Policy

- Bruce L.R. Smith(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

8

Birth of the Marshall Plan,1947–1948

It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine, but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.—George C. Marshall, June 5, 1947The essential function of the Marshall Plan was to make it politically and administratively possible for the Europeans to do in four years what otherwise couldn’t possibly be done in so short a period.—Milton Katz, 1975A fourth lesson [of the Marshall Plan] involves the interweaving of market forces and institutional factors, and the need to be wary of purist dogmatisms. . . . There were many novel experiments during those years. . . . Some succeeded, and others failed, but all involved mixtures of private enterprise and governmental framework-building; none were at the extremes of pure planning or pure market forces.—Lincoln Gordon, 1984Gordon did not attend the June 5, 1947, Harvard commencement exercises. He was busy with end-of-term activities. After resuming his teaching duties in January 1947, and with additional research and consulting responsibilities, he found it an effort to catch up with the scholarly literature, prepare his lectures, meet with students, and attend to myriad other academic tasks. The events in Europe were on his mind, however, and he also continued to follow closely what was happening at the UN with atomic energy. The Baruch Plan on atomic energy was clearly dead, due to a combination of Soviet intransigence and Pentagon opposition. President Truman and his congressional allies had won an important victory with the McMahon bill, establishing civilian control of atomic energy, but the military services were big winners, too, by keeping nearly everything connected with nuclear energy highly classified. - eBook - ePub

- Fernando Guirao, Frances Lynch, Sigfrido M. Ramirez Perez(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

This was the key American perception and understanding of the roots of the world wars, of the Great Depression, of totalitarianism, which fed the determination of that nation’s government to place the peace of the world on a different, non-European footing, after the Second World War provoked by Europeans in twenty-five years. This chapter will argue that the thinking which eventually produced the European Recovery Program (ERP, the Marshall Plan’s formal title) came from a lineage of American reflection about the relationship between prosperity and democratic progress which stemmed from that nation’s experience in World War I and at the Versailles peace conference. It was further developed as totalitarianism took hold in Europe in the context of the wars, threats of wars, and the Great Depression of the 1930s.These ways of looking at Europe then went into the great debate about the United States’ role in the postwar world which started across that country even before the war broke out, informed the planning effort which started in and around the State Department from 1940, could be seen in the long series of economic conferences organized by the Roosevelt administration during the war, and then profoundly colored attitudes toward the spread of Communism in the Old World, in the ruins left by the war.None of this explains the precise form which the Marshall Plan eventually took or its fairly chaotic and contradictory evolution in reality. Nor does it explain why the Plan emerged exactly when it did. As we shall see, the origins of the Plan were at the same time philosophical, political, and psychological. The gathering cold war was its immediate context and gave the operation an urgency which intensified over time, to the point where, after the Korean War emergency, military priorities took over entirely, and the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA, the agency running the Marshall Plan) gave way to the Mutual Security Agency. The East-West confrontation was not an affair of numbers, and its pressures were far more important in determining that something like the Plan happened than the dire balance of payments situation of Western Europe, which was the short-term, formal prompt for Congressional action. In the end it was politicians, technocrats, businessmen, and journalists who thought up the Plan and made it happen, not treasury people or central bankers, not the staff of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank or the Export-Import Bank, and certainly not the kind of public-private financier like Dawes and Young who had been so inventive in finding ways to save Germany in the 1920s. The most extraordinary thing about the Marshall Plan was not how key élite elements in the United States and Europe decided it was necessary—on that the political consensus at the. time was strong—but that it did in fact happen.2 - eBook - PDF

The Occupation of Iraq

Winning the War, Losing the Peace

- Ali A. Allawi(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

‘It would be neither fitting nor efficacious for this Government to undertake to draw up unilaterally a program designed to place Europe on its feet economically. This is the business of the Europeans. The initiative, I think, must come from Europe. The role of this country should consist of friendly aid in the drafting of a European program so far as it may be practical for us to do so. The program should be a joint one, agreed to by a number, if not all European nations.’ – George C. Marshall, addressing the commencement class of Harvard University, 5 June, 1947 ‘Our strategy in Iraq will require new resources . . . I will soon submit to Congress a request for $87 billion. This budget request will also support our commitment to helping the Iraqi and Afghan people rebuild their own nations, after decades of oppression and mismanagement. We will provide funds to help them improve security. And we will help them to restore basic services, such as electricity and water, and to build new schools, roads, and medical clinics. This effort is essential to the stability of those nations, and therefore, to our own security.’ – George W. Bush, addressing the American people, 3 September, 2003 ‘[The CPA] didn’t have [monitoring] systems set up. They were very dismis-sive of these processes . . . . The CPA didn’t hire the best people . . . . We were just watching it unfold. They [the CPA] were constantly hitting at our people, screaming at them. They were abusive.’ – Andrew Natsios, former administrator of USAID, in an interview with Newsweek , 22 March, 2006 14 A Marshall Plan for Iraq? The Marshall Plan, officially the ‘European Recovery Program’, was one the most important foreign policy successes of the United States after World War II. - eBook - ePub

The Laws That Shaped America

Fifteen Acts of Congress and Their Lasting Impact

- Dennis W. Johnson(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

59Crafting the Marshall Plan

A number of individuals have made paternity claims on the Marshall Plan. At the public level, Walter Lippmann, the influential columnist who was read widely at the highest levels of government decision-making, wrote a series of articles in March 1947 on the necessity of European recovery. In his “Today and Tomorrow” column, Lippmann warned of the imminent collapse of European economies: “The danger of a European economic collapse is the threat which hangs over us and all the world.” He argued that “the truth is that political and economic measures on a scale, which no responsible statesman has yet ventured to hint at, will be needed in the next year or so.” Lippmann warned that “our own officials shrink from the ordeal of explaining it to Senator Taft and those who see things as he does.”60 Ronald Steel, Lippmann’s biographer, asserted that Lippmann first suggested that the United States invite the Europeans to create their own plan for recovery.61In government circles, Forrestal, John J. McCloy, Henry L. Stimson, Harriman, John Foster Dulles, Paul Nitze, Bohlen, Kennan, Acheson, and others had been thinking and writing about aid to Europe since the end of the war. Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas argue that Harriman may have been the first to reduce his thoughts to paper. In one of his last cables from Moscow to President Roosevelt, Harriman urged a massive reconstruction aid program. Acheson, too, in drafting the Truman Doctrine, argued for a larger reconstruction program.62However, in the United States government itself, there was no inter-agency coordination, and no comprehensive plan that addressed the challenges of European recovery.63 The planning that occurred came primarily from the State Department. On March 11, Acheson established the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC), which a month later produced a report calling for a comprehensive recovery plan, with economic integration of Europe and reintegration of German as essential features.64 - eBook - ePub

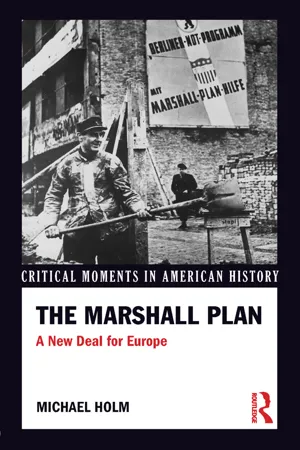

The Marshall Plan

A New Deal For Europe

- Michael Holm(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The nations that the Marshall Plan sought to uplift, in contrast, had a recent history of extensive bureaucratic structures, modern economic productivity, and political organization that mirrored the American experience to a far greater extent. In terms of intellectual rationale, however, the similarities between these programs were considerable. Both connected the traditional American mission to improve the weak and to stimulate democracy with the goal of saving countries from both Communism and their own economic and political quagmires. Both served ideological, economic, and national security purposes, and both were overwhelmingly inspired by a belief in the superiority of American methods and principles. 10 In Europe, the ECA took the lead role in institutionalizing this expansion of American socio-economic ways and means. During the summer and fall of 1948, the key executive body of the ERP began to channel grants for commodity assistance and program financing. In the first year of recovery support alone, $1 billion of the total amount authorized was meant to be available only through loans, usually bearing an interest rate of 2.5 percent. As it became apparent that loans forced Marshall Plan recipients to accept further dollar obligations, thereby increasing the dollar gap the ERP aimed to close, a growing proportion of aid shifted to grants. By year two, only $150 million came through loans, while some $3.6 billion arrived in the form of grants. Like modernization programs in the 1960s, technical assistance programs supplemented these grants. In a manner reflective of many of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, Hoffman’s technical assistance programs relied on top-down administrative procedures and training, and spanned a wide variety of sectors. The idea was that superior American business and production methods could be exported to Europe

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.