History

New England Colonies

The New England Colonies were a group of English colonies in North America, including Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire. These colonies were known for their Puritan religious beliefs, fishing and shipbuilding industries, and a focus on education. They played a significant role in the early history of the United States and were characterized by a strong emphasis on self-government and individual freedoms.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "New England Colonies"

- eBook - PDF

Colonial America

From Jamestown to Yorktown

- Mary Geiter, William Speck(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

Finding it unsuitable to use as a port, they moved 80 The American Context a few miles west to a better location they called New Haven. Unfor-tunately, they failed to get along with or to attract many settlers before becoming part of Connecticut. NEW HAMPSHIRE Another New England colony which initially failed to develop was New Hampshire. After acquiring land along the Merrimack and Piscataqua Rivers in 1622, Sir Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason sent out settlers to establish settlements there. These did not really take off until colonists from Massachusetts moved to them in the 1630s. Massachusetts then disputed the claim to the area, a dispute which was not finally resolved until 1679, when Charles II took it over as a Crown colony This rounded off the establishment of colonies in New England, for Maine remained part of Massachusetts during the colonial period. KING PHILIP’S WAR By the 1670s, New England had acquired a distinct identity. Puritanism was only one aspect of it, albeit one which stamped its mark on the character of Connecticut and Massachusetts. A story told by Cotton Mather early in the eighteenth century recounted how a preacher went from Boston to Cape Cod, where he met with indifference to his preaching from people who told him they had gone there ‘to catch fish’. Fishing, indeed, became a leading industry in a region where thin rocky soil and impenetrable forests made farming difficult. Although settlements spread quickly after the arrival of colonists from England, they expanded principally along the seacoast and up rivers rather than overland. Fish were consumed not just locally, but exchanged for goods from a surprisingly wide market, which included the Azores, the Canaries and Madeira. Above all, New England became closely tied to the West Indies once sugar began to be produced in Barbados and Jamaica. Fish, meat and wood were sold and molasses and sugar bought for use in the distillation of rum. - eBook - ePub

- John Bach McMaster(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

5. Other religious disputes led to the migration of people who settled (1635-36) in the Connecticut valley and founded (1639) Connecticut. 6. Between 1638 and 1640 other towns were planted on Long Island Sound, and four of them united (1643) and formed the New Haven Colony. 7. Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven joined in a league —the United Colonies of New England (1643-84).8. New Haven was united with Connecticut (1662), and Plymouth with Massachusetts (1691), while New Hampshire was made a separate province; so that after 1691 the New England Colonies were New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.9. The New England colonists lived largely in villages. They were engaged in farming, manufacturing, and commerce.10. For twenty years, during the Civil War and the Puritan rule in England, the colonies were left to themselves; but in 1660 Charles II became king of England, and a new era began in colonial affairs.[Illustration: THE CHARTER OAK, HARTFORD, CONN. From an old print.]FOOTNOTES

[1] On his map Smith gave to Cape Ann, Cape Elizabeth, Charles River, and Plymouth the names they still retain. Cape Cod he called Cape James.[2] The Puritans were important in history for many years. Most of the English people who quarreled and fought with King James and King Charles were Puritans. In Maryland it was a Puritan army that for a time overthrew Lord Baltimore's government (p. 52).[3] Read Fiske's Beginnings of New England, pp. 79-82.[4] The little boat or shallop in which they intended to sail along the coast needed to be repaired, and two weeks passed before it was ready. Meantime a party protected by steel caps and corselets went ashore to explore the country. A few Indians were seen in the distance, but they fled as the Pilgrims approached. In the ruins of a hut were found some corn and an iron kettle that had once belonged to a European ship. The corn they carried away in the kettle, to use as seed in the spring. Other exploring parties, after trips in the shallop, pushed on over hills and through valleys covered deep with snow, and found more deserted houses, corn, and many graves; for a pestilence had lately swept off the Indian population. On the last exploring voyage, the waves ran so high that the rudder was carried away and the explorers steered with an oar. As night came on, all sail was spread in hope of reaching shore before dark, but the mast broke and the sail went overboard. However, they floated to an island where they landed and spent the night. On the second day after, Monday, December 21, the explorers reached the mainland. On the beach, half in sand and half in water, was a large bowlder, and on this famous Plymouth Rock, it is said, the men stepped as they went ashore. - eBook - PDF

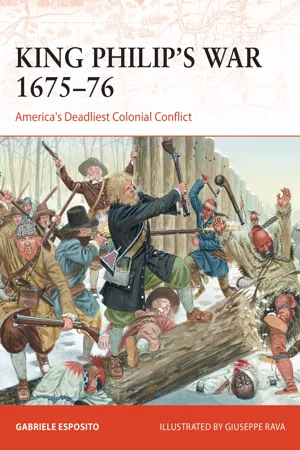

King Philip's War 1675–76

America's Deadliest Colonial Conflict

- Gabriele Esposito, Giuseppe Rava(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Osprey Publishing(Publisher)

These included smallpox, tuberculosis, cholera, and measles. Successive outbreaks had devastating impacts on the Native American populations in the 17th century. (Public domain) 18 the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. King Charles II sought to extend royal influence over New England, something that Massachusetts resisted with more determination than any other colony. The settlers repeatedly refused requests by Charles and his agents to allow the Church of England to become established on Massachusetts territory; in addition, they resisted adherence to any new law that could constrain colonial trade. For the Puritan colonists, the king had no authority to control the governance of the North American settlements. In order to resist the pressure coming from England, and to defend against possible attacks by the Dutch or Native Americans, Massachusetts concluded a formal military alliance with Plymouth and the other New England Colonies in 1634. As the New England Confederation, they would attempt to coordinate their militia forces for their common defense. The Puritans made no effort to include the other English colonies, Virginia and Maryland, which had been founded in 1632 by a group of Catholic refugees under a charter obtained by George Calvert from King Charles I. The New England Confederation, however, collapsed in 1654 when Massachusetts refused to join an expedition against New Netherland during the First Anglo-Dutch War. A map by Nicolaes Visscher of north-eastern America, showing New England (Nova Anglia, red) and New Netherland (Nova Belgica, yellow), originally published in Amsterdam in 1656. Green areas indicate those still under Native American control. The jurisdiction of Long Island (Lange Eylandt) was originally split between the Dutch and English, until 1664, when the English took over New Netherland, including Long Island. (Library of Congress; public domain) 19 By 1675, the number of English colonies in North America had grown to eight. - eBook - PDF

The Shaping of America

A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 1: Atlantic America 1492-1800

- D. W. Meinig(Author)

- 1986(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

The Piscataqua was an expression of an old and basic difference in English origins; Rhode Island was an American creation, a culturo-geographic manifestation of the social logic of certain Reformation ideas. Although an ema-nation from Puritanism and thus of the same British culture as its neighbors, Rhode Island, by establishing a different polity and a haven for religious dissenters of many kinds, attracted the sort of people who sustained a social divergence from the main New England pattern. That main pattern had been established by the remaining two nuclei, Mas-sachusetts and Connecticut. Fully Puritan in heritage, these two colonies con-stituted the core area of New England. Their continuance as separate political units would remain an important geopolitical feature, but they differed only in minor detail as to social and political character and thus constituted a solid culture area dominating the lowlands of New England. The basic character of New England was formed by the Puritans. The most distinguishing feature of Puritan colonization was its powerful emphasis upon the formation of Christian, Utopian, closed, corporate'* communities. The Bible provided the precepts; the New England wilderness, isolated from the corruptions and complexities of the Old World, provided the space for the practical adaptation of the model community, which would be accomplished by a people who explicitly agreed upon fundamental issues and covenanted to work together to build a new society. Those who dissented on basic matters could not be allowed to remain and jeopardize the common task. NEW ENGLAND 103 18. Two New England Settlements. New Haven and Wethersfield are two of the best known—and least typical—of New England settlement patterns. The famous nine squares of New Haven were surveyed in 1638 by the founding proprietors of the new colony on the Quinnipiac. - eBook - PDF

The Brief American Pageant

A History of the Republic

- David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl, , David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Left largely on their own, four colonies banded together to form the path-breaking New England Confederation . The confederation’s purpose was to provide Pequot War (1636–1638) Series of clashes between English settlers and Pequot Indians in the Connecticut River valley. Ended in the slaughter of the Pequots by the Puritans and their Narragansett Indian allies. King Philip’s War (1675–1676) Series of assaults by Metacom, King Philip, on English settlements in New England. The attacks slowed the westward migration of New England settlers for several decades. English Civil War (1642–1651) Armed conflict between royalists and parliamentarians, resulting in the victory of pro-Parliament forces and the execution of Charles I. New England Confederation (1643) Weak union of the colonies in Massachusetts and Connecticut led by Puritans for the purposes of defense and organization; an early attempt at self-government during the benign neglect of the English Civil War. H u d s o n R . C o n n e c t i c u t R . Long Island ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston Plymouth (Pilgrims) Salem Providence Springfield Hartford Cambridge New Haven Portsmouth 1679 Portsmouth CONNECTICUT 1635–1636 NEW HAVEN 1638 MASSACHUSETTS BAY 1630 RHODE ISLAND 1636 PLYMOUTH 1620 NEW HAMPSHIRE MAINE 1623 1 6 7 7 1 6 9 1 1 6 4 1 44°N 42°N 70°W 72°W N 0 0 50 100 Mi. 50 100 Km. Colonies absorbed by Massachusetts Bay Colony Colonies founded by migrants from Massachusetts Bay Colony Map 3.1 Seventeenth-Century New England Settlements The Massachusetts Bay Colony was the hub of New England. All earlier colonies grew into it; all later colonies grew out of it. Copyright 201 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. - eBook - PDF

The Long Process of Development

Building Markets and States in Pre-industrial England, Spain and their Colonies

- Jerry F. Hough, Robin Grier(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

243 7 The English Colonies It is difficult for modern Americans to develop a complex understanding of the English colonies. The first problem is generic to the history of all former colonies: historians naturally want to study the colonial antecedents of the independent country as it emerged from the empire. Yet the British did not even speak of the American colonies collectively until the 1730s, and then they had in mind all of their American colonies, not just those that became the United States. Indeed, in the 1600s the Caribbean colonies were economically and strategically far more valuable to England than the mainland colonies. Moreover, the Caribbean colonies were actually more integrated with the mainland colonies than the mainland colonies (or at least regions) were with each other. A free-market trade economy was created in New England and then in New York and Pennsylvania in order to supply food and materi- als to the slaves of Barbados and Jamaica. A second problem in understanding the colonies is that the elite of a post-independence country is naturally more interested in legitimating the new country than in exploring embarrassing aspects of the colonial past. Jamestown was the first permanent English settlement in the New World, 13 years before Plymouth, and it was vastly more important to London than Plymouth. Yet the Thanksgiving holiday focused on Plymouth because acknowledging, let alone celebrating, the real reason for colonization – the introduction of slave-produced tobacco –would have been awkward. Other distortions in colonial history were introduced for more specific political reasons. During the first half of the 20th century, the European Americans called themselves “races,” and they could feel as strongly about American policy toward their homelands as modern Cuban Americans feel about policy toward Cuba. This had a disastrous impact on American foreign policy and domestic politics in World War I, the interwar period, - eBook - ePub

- Ian Barnes, Charles Royster(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Such liberal developments in America were anathema to James II. The Navigation Acts were more vigorously enforced on the assumption that New England was a snakepit full of smugglers. To impose greater authority, James established the Dominion of New England, comprising NewYork, New England, and New Jersey. The assemblies were dissolved by Governor Andros, but he needed the consent of a nominated council to make laws and collect taxes. However, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 led by William of Orange and his wife, Mary, daughter of James, overthrew this autocratic Stuart who had incensed parliament by levying taxes without its sanction. New Englanders, New Yorkers, and Marylanders overthrew their hated government, but the new monarchs wanted to enforce strict authority. Massachusetts became a royal colony, like many other provinces, with a governor and court; legislation could be vetoed by the former, but the franchise was also extended. Pennsylvania’s 1701 Charter granted the lower house all legislative power, the council being appointive and advisory. Hence, despite royal interference, large measures of liberal and democratic development did exist with a strong legacy of self-rule and this situation was helped by the nature of British government. A whole range of institutions muddled and conflicted with each other, such as the Board of Trade and Plantations, which could evaluate colonial legislation and advise governments but had no real power. A variety of governors, assemblies, the customs service, and ministers for the colonies, together with army garrison commanders, all had their say. Thus, gentlemanly bedlam, decentralization, and calculated forgetfulness allowed the colonies to flourish. However, these soon faced the expense of costly Franco-British colonial wars in the Americas.The eighteenth century witnessed extensive settlement along the entire Atlantic seaboard with New England, the Middle Colonies, and the South being differentiated in economic and trade terms. Furthermore, a large measure of similar political representation and property enfranchisement existed with the bulk of the population being American-born or recently arrived non-English speaking immigrants. In the decades preceding the Revolution, certainly Massachusetts and its Puritan mentality distrusted British institutions and evolved a tradition of independence but also of intolerance towards others. The colony constantly re-examined its charter of 1629 and claimed that William and Mary’s version of 1691 had extinguished their rights and freedoms as English citizens, and this was discussed again in 1775. Massachusetts citizens looked back to the Cromwellian period of paternal neglect as a golden age of de facto independence and argued against the British view that colonists took no sovereign power with them to America, but Great Britain had seized sovereignty from Indian tribes and nations. Thus, parliament had acquired authority from the Native Americans by conquest, and local laws and assemblies could not alter this. By 1776, Massachusetts was demanding satisfaction of inalienable rights and government by contract. Thus, covenant theology theory became a construct through which colonials viewed British policy. Similarly, New York developed a non-conformist character as evidenced in artisan dissatisfaction and political assertion during the 1689 Leisler revolt against Andros, which led to Leisler’s later death by hanging. The growth of mob politics, and socioeconomic (class) cleavages became prevalent as colonial economies developed from semi-feudal, agricultural to capitalist ones during the early stages of modernization. American artisans also differed from the British variety in that labor was scarce and valuable and artisans used this as an economic and political lever to acquire higher wages, and they refused to accept a subordinate status or subscribe to British deference patterns. - eBook - PDF

A People and a Nation

A History of the United States

- Jane Kamensky, Carol Sheriff, David W. Blight, Howard Chudacoff(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

This must have made their lives in North America more comfortable and less lonely than those of their southern counterparts. 2-5b Contrasting Regional Demographic Patterns Puritan congregations quickly became key institutions in colonial New England. Anglican worship had less impact on the early development of the Chesapeake colonies, where 44°N 42°N 70°W 72°W H u d s o n R . C o n n e c t i c ut R. Long Island Cape Ann Cape Cod A T L A N T I C O C E A N ABENAKI POCUMTUCK POKANOKET MAHICAN MOHEGAN N A R R A G A N S E T T Boston Plymouth Salem Providence Springfield Hartford Wethersfield Newtown New Haven Portsmouth Newport CONNECTICUT NEW HAVEN MASSACHUSETTS BAY RHODE ISLAND PLYMOUTH NEW HAMPSHIRE MAINE (MASS.) NEW FRANCE N E W N E T H E R L A N D N 0 0 50 100 Mi. 50 100 Km. 44°N N 70°W W W W AKI 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Mi. Mi. Mi. Mi. Mi Mi Mi. Mi Mi Mi Mi. Mi. Mi. Mi. Mi. M Mi. Mi. M M Map 2.2 New England Colonies, 1650 The most densely settled region of the mainland was New England, where English settlements and the villages of the region’s indigenous Algonquian-speaking peoples existed side by side. Mayflower Compact Agreement signed by Mayflower passengers to establish order in their new settlement. Copyright 2019 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. CHAPTER 2 Europeans Colonize North America | 1600–1650 48 2-5f Governor John Winthrop In October 1629, the Massachusetts Bay Company elected John Winthrop, a member of the lesser English gentry, as its governor. Winthrop organized the initial segment of the Puritan migration to America. - Thomas N. Ingersoll(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

10 Historically minded New Englanders were guided by the past to be progressives, determined to pass on to their descendants relations of power that were contractual, based on natural and sacred rights, an order legitimated by common consent, to set an example for the human race. 11 They were outwardly loyal to the crown in 1763, even jubilantly so in the year of the Treaty of Paris, and they felt a Protestant affinity with the English and other British in a Christian world overwhelmingly dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. Despite all that, loyalty remained contingent for the majority of New Englanders, who remembered the republican promise of 1649 and the potential for royal tyranny. 12 They knew, however vaguely in many cases, that history showed time and again that popular sovereignty had to overtrump kingly power, if there were to be rights and social order. The Massachusetts founders had not fled from England as a persecuted minority with enthusiastic, separatist religious views, like the Pilgrims of Plymouth; nor had they sought to establish an independent “theocracy” cut off from the corrupt Mother Country. 13 They set out voluntarily to 18 The New England People in their Towns on December 16, 1773 create “a city on a hill” where there were no unconstitutional taxes, arbi- trary justice, established church, or standing army – where crown power remained under a dark cloud of suspicion and little exercised directly in New England. 14 They meant to create a true English nation and church in purified form, to set a standard for those back home to emulate. Their ministers prayed for the monarch on Sunday, and the crown could always veto any legislation coming out of any colonial legislature, but otherwise crown and Parliament were little in evidence in New England. Liberty was preserved by the virtuous politics of responsible citizens in their local governing institutions, not doled out by a monarch and ruling class.- eBook - ePub

- Daniel Webster, Andrew Jackson George, (Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

It would far exceed the limits of this discourse even to mention the principal events in the civil and political history of New England during the century; the more so, as for the last half of the period that history has, most happily, been closely interwoven with the general history of the United States. New England bore an honorable part in the wars which took place between England and France. The capture of Louisburg gave her a character for military achievement; and in the war which terminated with the peace of 1763, her exertions on the frontiers were of most essential service, as well to the mother country as to all the Colonies.In New England the war of the Revolution commenced. I address those who remember the memorable 19th of April, 1775; who shortly after saw the burning spires of Charlestown; who beheld the deeds of Prescott, and heard the voice of Putnam amidst the storm of war, and saw the generous Warren fall, the first distinguished victim in the cause of liberty. It would be superfluous to say, that no portion of the country did more than the States of New England to bring the Revolutionary struggle to a successful issue. It is scarcely less to her credit, that she saw early the necessity of a closer union of the States, and gave an efficient and indispensable aid to the establishment and organization of the Federal government.Perhaps we might safely say, that a new spirit and a new excitement began to exist here about the middle of the last century. To whatever causes it may be imputed, there seems then to have commenced a more rapid improvement. The Colonies had attracted more of the attention of the mother country, and some renown in arms had been acquired. Lord Chatham was the first English minister who attached high importance to these possessions of the crown, and who foresaw any thing of their future growth and extension. His opinion was, that the great rival of England was chiefly to be feared as a maritime and commercial power, and to drive her out of North America and deprive her of her West Indian possessions was a leading object in his policy. He dwelt often on the fisheries, as nurseries for British seamen, and the colonial trade, as furnishing them employment. The war, conducted by him with so much vigor, terminated in a peace, by which Canada was ceded to England. The effect of this was immediately visible in the New England Colonies; for, the fear of Indian hostilities on the frontiers being now happily removed, settlements went on with an activity before that time altogether unprecedented, and public affairs wore a new and encouraging aspect. Shortly after this fortunate termination of the French war, the interesting topics connected with the taxation of America by the British Parliament began to be discussed, and the attention and all the faculties of the people drawn towards them. There is perhaps no portion of our history more full of interest than the period from 1760 to the actual commencement of the war. The progress of opinion in this period, though less known, is not less important than the progress of arms afterwards. Nothing deserves more consideration than those events and discussions which affected the public sentiment and settled the Revolution in men's minds, before hostilities openly broke out. - eBook - ePub

- Jerome R Reich, Jerome Reich(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

7 The New England Colonies“So God brought me out of Plymouth and landed me at Nantassret. Blessed be God!” As may be inferred from this typical immigrant’s statement, religion was the primary—though not exclusive—motive for the settlement and expansion of New England. This chapter surveys the religious, political, and economic development of New England and its often clashing relationships with the Native American inhabitants.The Founding of the Plymouth Colony

In England, Separatists were punished by fines and imprisonment. The members of a small Separatist congregation at Scrooby in Yorkshire, tired of being “clapt up in prison,” left England in 1608 for Holland and religious freedom. It was this congregation of ordinary farm workers—led by William Bradford and their minister, John Robinson—whom we know as the Pilgrims. Although the Pilgrims found religious freedom in Holland, they faced difficult economic conditions, the assimilation of Dutch customs by their children and the possibility of involvement in a war between Holland and Spain that threatened to break out in 1621. Therefore, a group of them decided—in spite of the perils involved—to settle in the New World.In 1620, after much negotiation, the London Company gave the Pilgrims permission to settle on its territory. To help with finances, a merchant named Thomas Weston formed a joint stock company which raised the funds necessary to transport them to America. Each colonist was given one share in the company and was expected to work for the company for seven years. At the end of that period, all the land and profits were to be divided between the colonists and the other investors in the company. Thirty-five Pilgrims and sixty-seven other English men, women, and children boarded the Mayflower when it sailed for America in September 1620.The voyage lasted slightly over two months. Whether because storms blew them off course; or because the Pilgrims were attracted by John Smith’s account of the furs, fish, and timber in New England; or because they felt they would be freer to worship as they pleased outside the jurisdiction of the London Company, the Pilgrims landed on Cape Cod (not Plymouth Rock) instead of Virginia. This created a problem: How, and by whom, were they to be ruled? The solution to this problem was the famous Mayflower Compact, in which forty-one of the adult males agreed to - eBook - PDF

- David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Far to the north, enterprising fishermen and fur-traders had been active on the coast of Maine for a dozen or so years before the founding of Plymouth. After disheartening attempts at colonization in 1623 by Sir Ferdinando Gorges, this land of lakes and for-ests was absorbed by Massachusetts Bay after a formal purchase in 1677 from the Gorges heirs. It remained a part of Massachusetts for nearly a century and a half before becoming a separate state. H u d s o n R . C o n n e c t i c u t R . Long Island A T L A N T I C O C E A N Boston Plymouth (Pilgrims) Salem Providence Springfield Hartford Cambridge New Haven Portsmouth 1679 Portsmouth CONNECTICUT 1635–1636 NEW HAVEN 1638 MASSACHUSETTS BAY 1630 RHODE ISLAND 1636 PLYMOUTH 1620 NEW HAMPSHIRE MAINE 1623 1 6 7 7 1 6 9 1 1 6 4 1 44°N 42°N 70°W 72°W N 0 0 50 100 Mi. 50 100 Km. Colonies absorbed by Massachusetts Bay Colony Colonies founded by migrants from Massachusetts Bay Colony MAP 3.3 Seventeenth-Century New England Settlements The Massachusetts Bay Colony was the hub of New England. All earlier colonies grew into it; all later colonies grew out of it. Contending Voices Anne Hutchinson Accused and Defended In his opening remarks at the examination of Anne Hutchinson in 1637, Governor John Winthrop (1587–1649) declared: “ . . . you have spoken diverse things . . . very prejudicial to the honour of the churches . . . and you have maintained a meeting and an assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable . . . nor fitting for your sex. . . . ” Hutchinson (1591–1643) defended herself as follows: “ Will it please you to answer me this and to give me a rule for then I will willingly submit to any truth. If any come to my house to be instructed in the ways of God what rule have I to put them away? ” In what ways did the accusations against Anne Hutchinson go beyond doctrinal heresy? Copyright 2020 Cengage Learning.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.