History

Pat McCarran

Pat McCarran was a US Senator from Nevada who served from 1933 to 1954. He was known for his controversial views on immigration and his role in the creation of the McCarran Internal Security Act, which allowed for the investigation and detention of suspected communists during the Cold War.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

3 Key excerpts on "Pat McCarran"

- eBook - ePub

Unwanted

Italian and Jewish Mobilization against Restrictive Immigration Laws, 1882–1965

- Maddalena Marinari(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

79 Lastly, while diffidence lingered, many activists realized the value of interethnic and interreligious collaboration. American Jews were at the forefront of promoting cooperation as an effective strategy to neutralize anti-Communist hysteria and advocate for immigrant rights for all. Many Jewish activists felt that this was a natural progression, but they also realized that the creation of the State of Israel gave Jewish refugees a new destination and the Cold War made it hard for them to help Jews behind the Iron Curtain. Although much less active than American Jews in the 1940s, Italian Americans too learned that collaboration, especially with the Catholic Church, helped them advance the cause of Italian migration more effectively because it legitimized their professed anti-Communism and cast their ties with Italy in a positive light. These coalitions soon faced their hardest test yet.Between Restriction and Inclusion: The McCarran-Walter Act 1952

McCarran’s push for the Internal Security Act represented only the beginning of his larger plan to wrestle the reform process away from liberal immigration reform advocates. In January 1951, McCarran resurrected the immigration bill he had proposed a year earlier to protect U.S. democracy “in this black era of fifth column infiltration and cold warfare,” a not-so-veiled reference to what he elsewhere referred to as “Jewish interests.”80 With its combination of restrictive, anti-Communist, and Cold War civil rights measures, McCarran’s bill incarnated the political atmosphere of the early 1950s. While it retained the national origins quota system, introduced more screening measures, and tightened exclusion, deportation, and naturalization procedures, it also included a small quota for refugees, ended Asian exclusion altogether, and removed all remaining racial, gender, and nationality barriers to citizenship. Many of the civil rights measures revealed a continued preoccupation with maintaining the existing racial makeup of the United States, however. Although it abolished Asian exclusion, the bill granted only a minimal quota of 100 to each of the countries in the Asia-Pacific Triangle to remove, in McCarran’s words, “the present racial discriminations in a realistic manner,” and calculated Asian quotas on the basis of ancestral origin rather than place of birth. To restrict the growing flow of nonwhite immigrants from Jamaica, the bill introduced the first yearly quota (of 100) on immigration from the Caribbean islands under British rule, previously included in the generous British quota. At the same time, it continued to exempt the Western Hemisphere from the quota system to allow the importation of returnable and cheap Mexican workers.81 Lastly, the bill systematized and proposed a preference system that explicitly favored immigrants with family ties, education, and economic potential.82 - eBook - ePub

- John S. W. Park(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Polity(Publisher)

4 . See DAVID GARROW, BEARING THE CROSS (2004), and TAYLOR BRANCH, AT CANAAN’S EDGE (2007).5 . For a biography of Senator Pat McCarran, including a discussion of his role in the Immigration Act of 1952, see JEROME EDWARDS, Pat McCarran (1982). McCarran’s remarks appear in CONG. REC. (Mar. 2, 1953), on 1518.6 . For a “prehistory” of the Immigration Act of 1965, including Harry Truman’s veto of the rule in 1952, see IMMIGRATION AND THE LEGACY OF HARRY S. TRUMAN (Roger Daniels, ed., 2010). For a discussion of the Immigration Act of 1965, see THE NEW AMERICANS (Mary Waters and Reed Ueda, eds., 2007), and THE IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT OF 1965 (Gabriel Chin and Rose Cuison Villazor, eds., 2015).7 . See, generally, Edward Kennedy, The Immigration Act of 1965, 367 ANN. AMER. ACAD. POL. & SOC. SCI. 137 (1966). Kennedy’s remarks appear in US SENATE, SUBCOMMITTEE ON IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION (Feb. 10, 1965), on 8.8 . For a discussion of Johnson’s strategy for immigration reform, see JOSEPH CALIFANO, THE TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY OF LYNDON JOHNSON (2015).9 . Lyndon Johnson, Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill (Oct. 3, 1965). The entire text of this speech can be found on-line, at the American Presidency Project based at University of California, Santa Barbara.10 . For an overview of the American military presence in Asia in the twentieth century, see MICHAEL HUNT and STEVEN LEVINE, ARC OF EMPIRE (2012). For a discussion of how racist attitudes toward Mexico and Latin America had shaped American foreign policy in that region, see LARS SCHOULTZ, BENEATH THE UNITED STATES (1998). We can see there how American policy-makers saw Mexican nationals primarily as racially inferior people and as cheap sources of labor.11 . DAVID REIMERS, STILL THE GOLDEN DOOR (1992), and Gabriel Chin, The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law, 75 N.C. L. REV. 273 (1996).12 - eBook - ePub

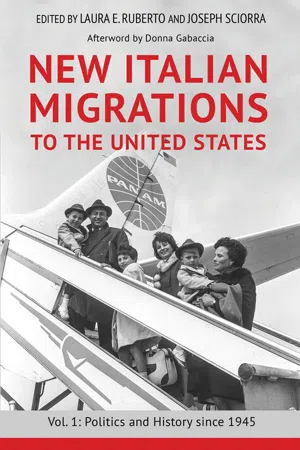

New Italian Migrations to the United States: Vol. 1

Politics and History since 1945

- Laura E Ruberto, Joseph Sciorra, Laura E Ruberto, Joseph Sciorra(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

Gazzetta del Massachusetts also played on the Cold War discourse to stigmatize the congressional decision. It argued that, by barring most prospective Italian immigrants from the United States the enforcement of the act meant erecting an “iron curtain” between two western countries (Felletti 1952). Likewise, on behalf of the Independent Order Sons of Italy, Peter C. Giambalvo (1952) maintained that the McCarran-Walter Act was out of synchrony “with our international policies and the battle or struggle we are engaged in together with many other democratic and friendly nations of Europe, against the tyranny of Moscow.”Representatives of the Italian American community also crowded the hearings of a commission that Truman appointed in the fall of 1952 to study U.S. immigration policy in the wake of the harsh debate on the McCarran-Walter Act, since the new legislation revealed its numerous shortcomings and inconsistencies with American political tradition. On this occasion, Luigi Scala of the OSIA and Nicola Gigante of the ACIM restated the connection between the Cold War and the provisions of U.S. immigration legislation concerning Italy. The former held that “the McCarran Act … has been resented by the people in Italy, who are bound to us as allies in the North Atlantic Pact … and is one of the reasons for the Communist strength in recent elections. … Our several forms of financial help to European countries have unquestionably been an antidote against communism; in the case of Italy it is equally important, if not more, to obtain outlets for its excessive manpower. By reducing unemployment there we shall stifle communism and shall help the long term economic stability of that country, thus making it a better ally.” The latter maintained that “UNRRA aid or Marshall Plan aid are not solutions to the problem of overpopulation. Financial help was necessary, but of temporary value. Nations such as Italy … can only be helped effectively by absorbing part, at least of their surplus manpower. Communism thrives where unemployment and poverty rule, and in unemployment and poverty lies the strength of the Italian Communist Party.” This was the leitmotif of several other testimonies by as many as twenty-two Italian American leaders in the field of politics, business, academic institutions, ethnic organizations, and the liberal professions, as well as editors and publishers of Italian-language newspapers. They criticized the recent reform for its biased contents and supported the repeal of the national-origin system so that the allotment of visas could reflect the actual needs of Italy and other Southern European countries that continued to be discriminated against under the existing rules to the benefit of northern nations whence mass emigration had long come to an end (U.S. House of Representatives 1952, 363–364, 613–614).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.