History

Plantagenet Dynasty

The Plantagenet Dynasty was a royal house that ruled England from the 12th to the 15th centuries. It is known for producing influential monarchs such as Richard the Lionheart and King John, as well as for its role in the Hundred Years' War. The dynasty's reign was marked by significant political and military developments, shaping the course of English history.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

5 Key excerpts on "Plantagenet Dynasty"

- eBook - ePub

Crown & Sceptre

A New History of the British Monarchy, from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II

- Tracy Borman(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Atlantic Monthly Press(Publisher)

Part 2 The Plantagenets (1154–1399)‘From the Devil they came and to the Devil they will return’The name Plantagenet applies to the three related ruling dynasties of Anjou, Lancaster and York: fourteen monarchs in total, their reigns spanning more than three hundred years.1 The most dynamic and energetic dynasty in British royal history, they fostered the legend that they were descended from Melusine, the daughter of Satan, who married an early Count of Anjou, then vanished in a puff of smoke when he forced her to attend Mass. The yellow broom flower that inspired their sobriquet was later embodied in the family arms. Henry II was the first and is generally agreed to be the greatest of the Plantagenet kings. His vast empire stretched from the Scottish border almost to the Mediterranean, and from the Somme in the north of France to the Pyrenees in the south. For much of the period, England waged costly wars with France and Scotland, with mighty warrior kings such as Edward I and III and Henry V achieving celebrated victories. Among the greatest contributions of the Plantagenets was the development of English law and their magnificent architectural legacy. The monarchy also evolved to become much more closely aligned with the interests of the people, while the rise of Parliament prescribed new limits on royal power.Passage contains an image

Henry II (1154–89)

‘A human chariot dragging all after him’WITH THE PEACEFUL accession of Henry II to the English throne in October 1154, the dynastic ambitions of his grandfather and namesake were not merely realised, but spectacularly superseded. England’s new king reunited Henry I’s Anglo-Norman inheritance, but also brought the lands and riches of Anjou and Aquitaine with him. He was compared to ‘a cornerstone joining the two peoples’ and, rather less accurately, as ‘a king of the English race’.1Like his great-grandfather, William the Conqueror, Henry II had already been chiselled into a fearsome warrior by the time he took the throne. Years of campaigning to protect his Duchy of Normandy had given him vital skills of diplomacy, too. Above all, he had youth on his side. He was twenty-one years old when he became King of England, and his restless energy and exuberance seemed boundless. The twelfth-century scholar Herbert of Bosham compared him to a ‘human chariot dragging all after him’.2 - eBook - ePub

Armies of Plantagenet England, 1135–1337

The Scottish and Welsh Wars and Continental Campaigns

- Gabriele Esposito(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Pen and Sword Military(Publisher)

Nevertheless, the first three exponents of the new dynasty are still commonly known as Angevin kings because they had important political interests and territorial possessions in France, and thus were still strongly linked to their home region of Anjou. Their successors were, however, definitely more ‘English’ in their outlook. The term Plantagenet, introduced by Richard of York, derived from the French nickname Plante Genest that was attributed to Geoffrey of Anjou. Genest was the French version of the Latin word Genista, which was used to indicate the flowering plant that we know as Scotch Broom. The nickname Plante Genest actually meant ‘the man who plants a Scotch Broom’. We don’t know if Geoffrey of Anjou really had a passion for this plant, but whatever the case, Richard of York decided to create a new name for his family from the nickname of his ancestor. Knight with falchion sword and kite shield. (Photo and copyright by Confraternita del Leone/Historia Viva) Knight with mace and sword. (Photo and copyright by Confraternita del Leone/Historia Viva) - eBook - ePub

- W M Ormrod, The British Library(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- The History Press(Publisher)

- 4 -

The House of Plantagenet 1272-1399

W.M. Ormrod

I t was the Angevin symbol of the sprig of broom, planta genista, that gave the House of Plantagenet its name; but while in origin the title might be supposed to date back to Henry II’s assumption of the throne in 1154, it was not in fact used by the English royal family until the fifteenth century. To call the kings of England from 1272 to 1399 ‘Plantagenets’ is therefore something of a fiction. There is, however, some justification for treating the rulers from Edward I to Richard II as a distinct group. First, although most of these kings attempted, in one way or another, to regain the French territories lost under King John and Henry III, they also gave much attention to the British Isles: this was the period in which the English monarchy not only clung tenaciously to its claims to the lordship of Ireland but also conquered Wales and attempted (and failed) to subdue the independent kingdom of Scots.It was during the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries that the English monarchy therefore gave its first indications of a coherent ambition for the unification of the British Isles. Secondly, the loss of the overseas territories meant that, to pursue their wars, rulers were dependent on the resources of the kingdom of England, and had to enter into tax negotiations with their subjects through the newly evolving institution of Parliament. Finally, this was a period during which two kings – Edward II and Richard II – were forced to give up their thrones through their incompetence and tyranny. The latter of these depositions brought to an end the direct line of descent of the English crown and heralded the arrival of a new dynasty, the House of Lancaster.EDWARD I (1272-1307)

The first king since the Norman Conquest to bear the Old English name of Edward was born on 17 June 1239, the first child of Henry III and Queen Eleanor of Provence. Edward and his younger brother, Edmund ‘Crouchback’, were both named in honour of Anglo-Saxon royal saints: Henry III’s devotion to Edward the Confessor is well known, but he also had a strong attachment to the cult of St Edmund of East Anglia, centred at Bury St Edmunds. Edward was trained in the school of hard knocks: his emergence to manhood and public life coincided with Henry III’s quarrel with the English barons, and Edward early earned himself a reputation not merely for the vigour and ruthlessness that would be a hallmark of his kingship but also for a tendency to shift his loyalties: he moved from being a supporter of Simon de Montfort’s reform programme to being his bitterest enemy; and after the Battle of Evesham, in which the prince decisively defeated the opponents of the Crown, he was commemorated in verse as one who changed his allegiance in the same way that the leopard was then believed to change its spots. - eBook - ePub

Kings & Queens of Great Britain

Every Question Answered

- David Soud(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Thunder Bay Press(Publisher)

The House of PlantagenetW ith the arrival on the English throne of Henry II, member of the House of Plantagenet, England entered the glittering age of its first imperial splendor. The Plantagenets were the most deeply and colorfully French of the British monarchs, and they brought to the English court the sumptuous pageantry, chivalric ideals, and dynastic intrigues of the southern realms of Anjou and Aquitaine. While some Plantagenet kings, such as Richard I, the Lionheart, regarded England as something of a backwater, Edward I and Edward III surely number among Britain’s greatest monarchs, and the tragically self-destructive reign of Richard II brought to an end a truly extraordinary dynasty.HENRY II The First Imperial King of England

W hen Henry Plantagenet, of the House of Anjou, was crowned King of England at the age of twenty-one, he already possessed vast holdings in France through inheritance and marriage. Those resources, and the force of his character, made him the strongest English monarch in generations—until his sons began to maneuver against him.House PlantagenetBorn March 5, 1133Died July 6, 1189Reigned 1154–1189Consort Eleanor of AquitaineChildren Eight, including Richard I and JohnSuccessor Richard IDuring the civil war, barons had built unauthorized castles throughout England. One of Henry’s first priorities was to raze them in a show of authority. He was an expert in siegecraft.HE IS A GREAT, INDEED THE GREATEST OF MONARCHS, FOR HE HAS NO SUPERIOR OF WHOM HE STANDS IN AWE, NOR SUBJECT WHO MAY RESIST HIMARNULF OF LISIEUXWhen Henry took the throne, he faced the twofold challenge of restoring order and stability in England and retaining control of his many lands on the continent. He embarked on both enterprises with a dynamism that astonished friends and enemies alike. Henry’s tireless traveling throughout his lands—he was known to wear out horses with hard riding—reinforced the sense that he was very much the master of his realms. - eBook - ePub

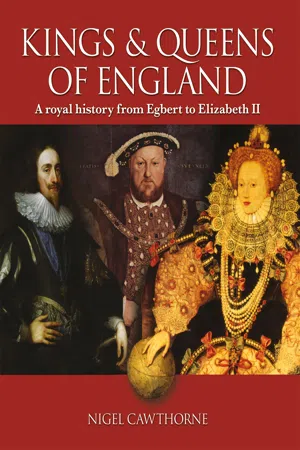

Kings & Queens of England

A royal history from Egbert to Elizabeth II

- Nigel Cawthorne(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Arcturus(Publisher)

Henry II came to the English throne in 1154 – he was the first in a line of fourteen Plantagenet kings. The dynasty would last for more than 300 years. He was short and stocky with legs slightly bowed from endless days on horseback and his hair was reddish, although he kept his head closely shaved. But his blue-grey eyes were his most distinctive feature. They were said to be ‘dove-like when he was at peace’ but ‘gleaming like fire when his temper was aroused’.Henry spent his life travelling around his possessions, which stretched from the Solway Firth to the Pyrenees. Although he reigned for 34 years he spent just 14 of them in England. The marriages of Henry’s three daughters had also given him influence in Germany, Sicily and Castile. In addition to that, Pope Adrian IV (in office 1154–9), the only English pope, gave Henry the right to rule Ireland. He obtained the homage of the Scottish kings, took Northumberland back from them and invaded Wales. However, all of his achievements were overshadowed by his quarrel with Thomas Becket, known to history as Thomas à Becket.THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

H enry II and his royal descendants are referred to as the House of Anjou or the Angevin dynasty. Plantagenet was not the surname of Henry’s father, Geoffrey V, count of Anjou, but it was instead a nickname. Some say he was dubbed Plantagenet because he liked to wear a sprig of broom (or Planta genista in Latin), others suggest that he planted broom to improve his hunting covers. However, the nickname did not become a hereditary surname. His descendants in England remained without a surname for over 250 years, even though surnames became universal for non-royals.Some historians suggest that only Henry II and his sons Richard I and John I should be known as the Angevin kings while their descendants, particularly Edward I, Edward II and Edward III, should be called Plantagenets. But the only occasion on which the name Plantagenet was used officially was in 1460, when Richard, duke of York, claimed the throne as ‘Richard Plantaginet’.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.