History

Post Classical Era

The Post Classical Era, also known as the Medieval Period, refers to the time between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. It was characterized by the spread of Islam, the rise of feudalism in Europe, and the flourishing of trade along the Silk Road. This era saw the development of new political, economic, and cultural systems that laid the foundation for the modern world.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Post Classical Era"

- eBook - PDF

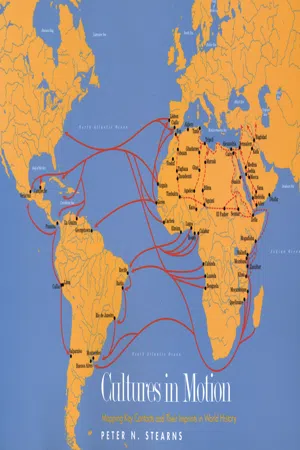

Cultures in Motion

Mapping Key Contacts and Their Imprints in World History

- Peter N. Stearns(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

Part II Postclassical and Early Modern Periods, 450–1750 CE The great classical empires fell or readjusted between 200 and 500 CE. Unity in the Mediterranean was shattered permanently with the collapse of Rome; China went through a long period of political disor-der; India returned to more regional political patterns with the end of the Gupta empire. These developments set the stage for a new wave of cultural contacts. Precisely because political arrangements began to misfire, people were open to new belief systems, particularly through religion, that would provide different kinds of assurances. Revision of political boundaries also opened the way for new travels by merchants, missionaries, and migrant peoples. The postclassical period (450–1450) saw the establishment of much more regular trading contact between Asia, Africa, and Europe. The principal routes ran east–west, from China and southeast Asia to the Middle East and East Africa, and from the Middle East to Europe. But subsidiary routes connected sub-Saharan Africa with the Middle East, both northwestern and northeastern Europe with the Middle East and Africa, and Japan with China. This intricate network obviously accel-erated cultural exchange. The new religion of Islam was most elabo-rately involved in this process, as both a cause and a consequence of expanded patterns of contact, but there were other results as well. The spread of world religions, launched earlier, accelerated, establish-ing much of the new framework for world history in the postclassical centuries. Chapters 3 and 5 outlined ongoing contacts resulting from Christianity and Buddhism. The development of Islam, beginning in about 600 CE, added a tremendous spur to cultural outreach, as this religion outpaced all others for several centuries. - eBook - ePub

- Mark S. Johnson, Peter N. Stearns(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part II The Postclassical Centuries

DOI: 10.4324/9781315817354-6The postclassical centuries, following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West and the Han dynasty in China, were defined by a complex combination of continuity and change. Key features of the Roman Empire and classical Mediterranean civilization were carried forward in the Byzantine Empire, while the imperial and Confucian tradition revived strongly in China. Hinduism consolidated its hold in much of India. But major missionary religions expanded their territories and gained a greater role in several societies – and this included the new religion of Islam, founded shortly after 600 CE. Trade expanded, with new commercial links among key parts of Asia, Europe and Africa. And new civilization centers emerged in Northern Europe, West Africa, Japan and the Americas.Educational developments in the centuries after the fall of the great classical empires, from about 500 CE to about 1450 CE, reflect a similar combination of established features and major innovations. As some societies recovered from the collapse of the empires, leaders often sought to restore school systems that had worked well in the past: this was most obviously true in China, but it also applied to the Byzantine Empire and to India. Restoration often extended some of the classical achievements in new ways, as in the more formal implementation of examinations in China, but they built on a solid base.But the postclassical centuries also introduced the three significant changes that greatly altered the framework of the classical era and directly affected education. In the first place, the role of organized religion in schooling surged forward once again (though in India and also in Judaism this built on established traditions). The new religion of Islam, rising and rapidly expanding after 600 CE, particularly contributed to educational development, but Christian schools gained additional importance as well. The expansion of Buddhism affected education too, particularly in East Asia. In several regions, religion furthered a striking surge in advanced educational institutions. Schooling and religion had been linked before of course, in the need to train religious officials (as with Hinduism). Now, however, religious motivations expanded, to fill growing ranks of priests and imams but also to satisfy the needs of many students to expand their understanding. - eBook - ePub

A History of Science

From Agriculture to Artificial Intelligence

- Mary Cruse(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Arcturus(Publisher)

PART TWOTHE POST-CLASSICAL ERA

5TH–15TH CENTURIESTHE POST-CLASSICAL ERA – which roughly corresponds to the Middle Ages – is often thought of as a dark time in human history, a time when science gave way to ignorance and superstition. There is some truth in this; after the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, scientific progress slowed and much knowledge was lost. But this period also saw genuine scientific innovation and advancement. This was particularly true in the Islamic world – here, classical scientific knowledge from Greece and Rome was preserved and eventually transported to Western Europe through booming trade networks and war. In Song dynasty China, a spike in industry coincided with a spate of groundbreaking engineering projects and inventions, including moveable type printing, gunpowder and paper money.Scientific endeavour in Eurasia was set back by the outbreak of the Black Death in the 14th century – a fearsome pandemic which killed millions of people and decimated the populations of Europe and the Middle East. But the end of the post-classical period saw an upsurge in cultural activity, culminating in the European Renaissance from the 15th century. To dismiss the post-classical era as a quiet, backwards period between two eras of enlightenment is to overlook the many scientific and technological advancements made during this portion of human history. Far from its characterisation as a ‘dark age’, the post-classical era saw thinkers and innovators continue the pursuit of scientific truth and enlightenment.Passage contains an image

CHAPTER 4 GEOGRAPHY

‘Geography is an earthly subject, but a heavenly science.’ – EDMUND BURKE, IRISH POLITICIAN AND PHILOSOPHERGeography – which translates from the Greek for ‘earth description’ – is the study of places, their physical features and the interactions between people and the environment. Although the word originates in Ancient Greece, people have been practising geography in some form all over the world for centuries. Geography flourished in Ancient Greece, but it became its own profession in Ancient Rome. In the post-classical era, the study of geography made great strides in the Islamic world, supported by Middle Eastern scholars’ profound knowledge of mathematics, eventually returning to Europe during the Renaissance. These events set the stage for the great explosion in geographic study that took place in the 18th and 19th centuries. - eBook - ePub

- Peter N. Stearns(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The classical civilizations did not introduce massive changes into their systems of punishment. They clearly retained many of the innovations already generated by the early governments that had operated in their regions. But they did modify, and the results, as well as the motivations for change, are worth attention. At the same time, the classical period also featured a variety of philosophers who began to ponder the nature and purpose of punishment; they may not have been the first to do so, but they are the first for whom records exist. The results did not necessarily alter the actual systems in effect—this was an interesting issue in China, for example—but they could generate new debate, both at the time and subsequently.The major classical systems collapsed between 200 and 600 CE, victim to internal disarray and external invasion. Their collapse was not complete or necessarily permanent; both in India and China, major classical features survived or were ultimately restored. But the unity of the Mediterranean was broken, opening the way to new forces, such as the religion of Islam, and in much of Europe to a prolonged period of political disunity.This in turn set the stage for what many world historians call the postclassical period, running from about 500 CE until the 15th century. The postclassical period was itself was marked by several key features:- Organized civilizations spread to new regions, including new parts of sub-Saharan Africa, northern Europe, Japan, and additional areas in the Americas. Governments in most of these regions were characteristically rather weak, but they did work to establish basic political systems including some of the apparatus of punishment.

- Transregional trade increased among much of Asia, key parts of Africa, and Europe. This led to a variety of other exchanges, including new technologies such as the compass, but the impact on approaches to crime and punishment was limited at best.

- The importance of religion increased. This was not a new factor in human affairs, and Chapter 3

- eBook - ePub

- Stephen Gosch, Peter Stearns(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Part IIThe post-classical periodTravel in the centuries after about 500 CE took on new dimensions, compared to its counterpart in the classical period. The most heroic individual travelers now covered longer distances, contacting even more diverse societies. The rate of travel increased. Travel also began to generate more significant consequences, particularly in supporting new trade contacts and the spread of world religions. Travel indeed became an integral part of an accelerating network of contacts among Asia, Africa, and Europe.Several factors account for the changing dimensions of travel. The advent of new religions, notably Islam, or growing interest in other religions such as Christianity and Buddhism was crucial. As religion became less localized, travelers could gain a sense of divine support even as they penetrated far-flung lands. They could also find fellow believers, even in very different cultural and political settings, who would help them in their journeys and provide some familiarity amid strangeness. Religion also provided a new motivation for travel, to promote conversion or to seek contact with the wellsprings of faith in distant places.Political change could be crucial. New or revived empires—the Arab caliphate, the reestablishment of empire in China—provided political protection for travelers across considerable geographic space. The interlocking Mongol empires, toward the end of the post-classical period, promoted security and offered explicit invitation to travelers over an unprecedented range of territory.Technology would enter in as well, though partly as a result of travel and trade. New ship designs, particularly by the Arabs, encouraged wider use of the Indian Ocean. New navigational devices would enter in toward the end of the period, headed by the compass. Travel and trade, particularly initially from Islamic lands, provided maps of unprecedented accuracy as well, another result of travel that could promote further travel in turn. Finally, as we will see, the increased output of travelers’ accounts provided both motivation and knowledge for other ventures, as travel began to feed on itself. - eBook - ePub

Global History

A Short Overview

- Noel Cowen(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Polity(Publisher)

The belief patterns now became the dominant factor, drawing into their own ambit the surviving political processes and using for their promotion whatever advances in economic processes were available and appropriate. Outstanding among these were materials and methods to increase the reach and permanence of written records and to provide impressive structures where the approved doctrines could be expounded and approved rituals consecrated. Surviving political elites manoeuvred to participate in the content and the control of the now dominant ideological factor. As their rivalries came to be mirrored in the competing sects and schisms of the aspiring religious organizations, a mood of profound searching became endemic across the regions of fading imperial rule.In the centuries following the crisis of belief the religious movements reorganized and regrouped under their own authority, strengthened by their core commitments as they assumed the care of their congregations and provided guidance and intellectual resources across the abandoned territories of the classical empires.Passage contains an image From Classical to Modern

This survey of the classical era has been constructed around the successive experiences of regional civilized societies, expanding political empires and would-be universalist churches. But how much justification is there for seeing the classical era as a part of global history? And what value is there in the grid of phases and factors in ordering the historical data? Part of the answer to the first question lies in the way the penetration of the global habitat set the scene for developments on a worldwide scale. Sedentism appeared independently at numerous sites, and villages became the norm of settled habitation. From this point the sequences of the settlements began to appear. In terms of the answer to the second question, the understanding of history in terms of the framework of phases and factors, it is apparent that from the beginning of the settlements the human experience centred around three basic community requirements: getting a living, working together and sharing ideas. All of these were always in play, sometimes one and sometimes another taking the lead. - Simon Samuel(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- T&T Clark(Publisher)

15 In both cases these postclassical writers of the ancient world and the postcolonial writers of the modern and postmodern world appear to be creative, imaginative writers of postcolonial fictions who write back to the respective empires of their time. 2. The colonial/postcolonial world of postclassical creative writings There is a general consensus among classicists that a new type of creative (nov-elistic) literature emerged in the postclassical middle or late Hellenistic and early Roman imperial times in regions around the eastern Mediterranean. This appears to be in association with a new phase in the political and cultural life of die peoples in the Hellenistic and Roman world. This new phase of political reality began with the extension of the power of Macedon in what is now northern Greece, by Philip and Alexander over the old cities of Greece from the mid-fourth century BCE. Before Alexander, Greece consisted of a number of small city-states around the Aegean, bound together by a common language and culture but politically divided into varying constellations. 16 After Alexander, Greek civilization spread over large parts of the east, and political power passed to big new monarchies with their centres in Macedonia/Asia Minor, Syria/Mesopotamia, and Egypt. During Hellenistic times (330-30 BCE) as the Hellenistic empires (of the Seleucids and Ptolemies) extended their borders to India and Egypt new Greek cites (in the form of colonies) were also founded at certain key centres of the empire. Indigenous peoples lived around, outside, and sometimes inside these Greek cities and had some cultural impact on them. At the same time it is self-evident that the majority of the peoples in the new kingdoms, especially in the countryside, kept their own culture and language.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.