History

Salt Route

The Salt Route was a historical trade route used for transporting salt from production centers to areas where it was in high demand. This route played a crucial role in the economic and cultural exchange between regions, as salt was a valuable commodity for preserving food and enhancing flavors. The Salt Route facilitated trade and contributed to the development of various civilizations along its path.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

3 Key excerpts on "Salt Route"

- eBook - ePub

Religious Pilgrimage Routes and Trails

Sustainable Development and Management

- Daniel H Olsen, Anna Trono, Daniel H Olsen, Anna Trono(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- CAB International(Publisher)

Among the most famous are the Silk Road, the Spice Routes, the Tea Route, the Frankincense Route, the Trans-Saharan Trade Route, the European Salt Roads, and countless others of lesser acclaim (Timothy and Boyd, 2015). The Silk Road is perhaps the best-known and documented ancient trade route, extending its several branches from eastern China, through Central Asia and into Europe. This nearly 7000-km route was used for trading silk from China for gold, silver and wool from Europe during the Roman Empire until the fifteenth century. It also became a corridor for disseminating technology, art, religion and culture (Foltz 1999 ; Whitfield 2004). Salt-based trade routes developed throughout Europe, Africa and Asia, with salt being one of the rarest and most valuable exchange commodities in antiquity. The Salt Routes of Europe were important commercial pathways anciently, and today several of the salt trails have been mapped and delineated as important heritage resources with potential for tourism development (Cianga et al., 2010 ; Rybár et al., 2010). The majority of global trade routes cannot be easily traversed, as they include land and sea routes, cover vast distances, would require the crossing of many international borders, and traverse many insecure regions. The logistics of operationalizing these as tourist routes are difficult at best. Nonetheless, several international organizations, such as UNESCO, are working to evaluate, delimit, map, demarcate and, in some cases, promote, these ancient trade trails, or at least portions of them, for tourism (Boyd et al., 2016) and as a mechanism to encourage cross-border cooperation between countries as a tool for regional development. Explorer, settler and migration routes In common with trade corridors, long-distances, crisscrossing political boundaries, and negotiating a wide range of natural and cultural landscapes typify explorer and migration routes (Lemke, 2017 ; Timothy and Boyd, 2015) - eBook - ePub

Tourism and Trails

Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues

- Dallen J. Timothy, Stephen W. Boyd(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Channel View Publications(Publisher)

For millennia, humans have traveled away from home for commerce. Buying and selling agricultural produce, manufactured items or the products of hunting and fishing, people have long traveled great distances by foot, horse, carriage and watercraft for trade. Many trade routes became famous and provided the fodder of great literary works and worldwide legends. Some ancient channels of commerce functioned for centuries until modern transportation methods replaced traditional corridors, while some still function today. Several historic and well-known market routes have garnered the attention of supranational alliances. These organizations (e.g. the World Tourism Organization or UNESCO) aim to establish long-distance cultural routes based upon the commercial activities that once defined them.Perhaps one of the longest and most complicated trade routes (gold, ivory, silk and bronze) to have existed in recorded history was the Silk Road, which operated between 300 BC and the 14th century AD. Spanning nearly 7000 km from China in the east to southern Europe in the west, the Silk Road comprised many interconnected branches and sub-routes (Misra, 2011; Tang, 1991). The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (1996) and UNESCO (Shackley, 2003) have since the early 1990s had an interest in developing the Silk Road as a viable tourism product through Asia and the Middle East to afford modern travelers the opportunity to walk in the footsteps of Marco Polo and the trade routes that connected Asia and Europe in the past. The Silk Road has been a longstanding project of the UNWTO since 1994, today involving 24 countries all linked by a special promotional logo. There have been three circles of involvement as to how the project has been promoted and developed over time. The first circle of involvement focused on encouraging the Central Asian countries to open their borders to tourism. The UNWTO has been able to help these countries prepare for tourism through the development of action plans, assisting with tourism workforce training, as well as working with government bodies to write legislation that affords ease of movement across borders. The second circle involved working with countries that have relatively open borders with respect to tourism, including in particular China, Pakistan and to some extent Iran. The focus here on sections of the Silk Road that traverse these countries is to strengthen tourism development. The last circle of involvement focused on countries at the start and end of the ‘road’, namely Japan, the Koreas and Southeast Asian countries at one end, and the Arab and European countries at the other. Here the UNWTO has focused on creating greater awareness of the Silk Road in the main and emerging tourism-generating markets. Efforts have been made by the UNWTO to market various sections of the route, particularly through China and the countries of Central Asia, using package tours, flight connections, train services and automobile travel on major roadways. China and Uzbekistan are the two countries most dependent on Silk Road-based tourism (Shackley, 2003; Tang, 1991). - eBook - ePub

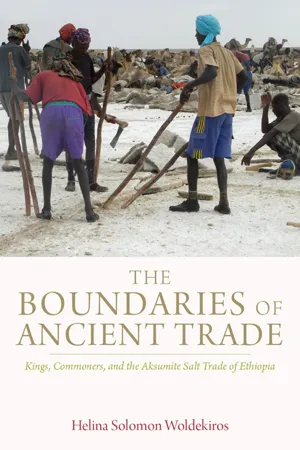

The Boundaries of Ancient Trade

Kings, Commoners, and the Aksumite Salt Trade of Ethiopia

- Helina Solomon Woldekiros(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University Press of Colorado(Publisher)

4The Historical, Physical, and Cultural Landscapes of the Afar Salt Trade

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781646424733.c004When I undertook fieldwork between 2009 and 2012, I did not assume that the nature and parameters of salt production and trade had remained constant throughout history. Indeed, political institutions, labor organization, ideologies, market systems, land tenure systems, and environmental conditions have all shifted since the pre-Aksumite period. I was aware that I needed to account for these changes. At the same time, certain aspects of the traditional salt industry have remained consistent since the Aksumite and medieval periods: the use of donkeys, mules, and camels; block salt mining technology; the landscape; the climate; and the location of rivers and mountain passes. These unchanging aspects of the industry allowed me to create ethnographic analogies that I use as comparative models (rather than as literal representations of the past) (following Stahl 2001). A study of contemporary practices in modern salt production and trade along the Afar route, approached relationally (sensu Wylie 2002), helps refine which questions about the distant past I pursue. With such queries in mind, I examine the source-side (ethnographic) data and the subject-side (archaeological) data separately, looking for similar and dissimilar patterns. I expand on the analogies by examining additional sources, such as historical documents and inscriptions.For example, to understand the ancient salt trade and its role in the Aksumite economy, it is useful to explore the modern locations of salt resources, the scale and intensity of production, the locations of processing areas (i.e., whether they are near salt sources or in central urban or rural towns), the categories of participants (both elite and non-elite), the relationships among participants, and the relationships between the state and salt producers and traders. This information about the contemporary salt trade may indicate areas for further archaeological inquiry into the Aksumite salt trade, such as how people shared resources and negotiated social relationships. This further inquiry could deepen our understanding of the Aksumite state’s growth, reach, and sustainable income sources, including alliances the Aksumites established with local and long-distance trading partners to acquire state goods.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.