History

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Born into slavery, she escaped to freedom and became a powerful advocate for the rights of both African Americans and women. She is best known for her powerful speech "Ain't I a Woman?" delivered at the Women's Rights Convention in 1851, which highlighted the intersectionality of race and gender in the fight for equality.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Sojourner Truth"

- eBook - ePub

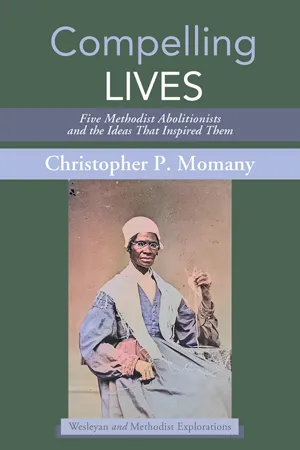

Compelling Lives

Five Methodist Abolitionists and the Ideas That Inspired Them

- Christopher P. Momany(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

1851 “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech has been contested by commentators for years. Newspaper accounts of that address, along with several attempts at transcribing what was heard, have left generations unsatisfied. Whose recollection captured the essence of Sojourner Truth? How did cultural assumptions of the time distort the speech? If one peeled back the layers of memory, could one get to her exact words?Such questions have a way of backfiring on us. Those who deconstruct various printed versions of this speech typically claim to be unleashing the real Sojourner Truth. But even these efforts manipulate more than they liberate. Attempts to reach the pure message presume that she requires someone else to free her. We should always remember that, even though state law released Truth in 1828 , she walked away from slavery on her own terms before then, and the only one who ever really freed her was the God who loved her.121On April 26 , 1850, the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator carried the following announcement: “JUST PUBLISHED, And for Sale at the Anti-Slavery Office, 21 Cornhill, NARRATIVE OF Sojourner Truth, a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York in 1828 . With a Portrait.”122 This very paper also contained blistering commentary aimed at the pending legislation in Washington that would nationalize the recapture of people leaving slavery. April 1850 was a critical month for Sojourner Truth. It marked the agency and self-determination that comes with being a homeowner, the premiere of her autobiography, and the ominous foreshadowing of so-called Fugitive Slave legislation. As her personal life became better established, the nation stumbled toward even more systematic oppression.Frederick Douglass feared that any law mandating the nationwide pursuit of those escaping bondage would drive thousands on to Canada. He labeled the legislation the “Bloodhound Bill.” When enacted in September of 1850 , the new law served as an accelerant for the fire consuming America.123 Many abolitionists referred to the act with disdain; they continued to call it the “Fugitive Slave Bill,” even after it was signed. Nothing so contrary to the divine will could ever be termed a legitimate law.124 - eBook - ePub

Preaching God's Transforming Justice

A Lectionary Commentary, Year B

- Ronald J. Allen, Dale P. Andrews, Dawn Ottoni-Wilhelm, Ronald J. Allen, Dale P. Andrews, Dawn Ottoni-Wilhelm(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Westminster John Knox Press(Publisher)

Sojourner Truth Day (August 18)JoAnne Marie Terrell

JEREMIAH 3:19–25PSALM 106:1–5, 40–482 CORINTHIANS 3:12–4:2LUKE 1:26–38Born into slavery about 1797 in Ulster County, New York, Isabella Baumfree experienced a religious conversion and call to public ministry in 1843.1 New York, like other northern states, had “gradual” emancipation laws, but Isabella knew in her heart that God had already set her free. So she “told Jesus it would be all right if he changed [her] name” because when she left the state of bondage she wanted “nothin’ of Egypt” left on her account. According to her story, the name Sojourner was given to her in a vision, for she understood that she was to walk about the country preaching and doing God’s will. To this name she added Truth, becoming a great advocate in the cause of freedom from oppression for African Americans and women.An extraordinary orator, Sojourner followed her call to lecture and preach for the rights of women and the abolition of slavery. Her work included advocating for black soldiers during the Civil War, opposing the death penalty, and calling for other civic liberties. Her speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” addressed to the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in 1851, is among the most persuasive, moving, and timeless testimonies to the God-given rights of women. On this Holy Day for Justice, when we celebrate women’s suffrage in the United States, we remember Sojourner Truth’s powerful and enduring civil rights ministry on behalf of women, African Americans, and all God’s people.Then that little man … says, “Women can’t have as much rights as men, because Christ was not a woman.” Where did your Christ come from? … From God and a woman. Man had nothing to do with him.2 - eBook - PDF

Women Public Speakers in the United States, 1800-1925

A Bio-Critical Sourcebook

- Karlyn Kohrs Campbell(Author)

- 1993(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Sojourner Truth (1797?-1883). legendary anti-slavery and woman's rights agitator SUZANNE PULLON FITCH Sojourner Truth was an advocate for anti-slavery and woman's rights. As a freed Black woman, she epitomized both causes and from this position gained much of her influence as spokesperson for both reforms. As a slave, Truth was denied any opportunity for an education, and even after gaining her freedom, she never learned to read or write. Thus, extant texts of her speeches were transcribed by others as she spoke; probably none is accurate. Because they were transcribed, most of the content is fragmentary at best, and often the only records are reports of what she said that quote a phrase or two to show her ability to make a point. A further problem in quoted fragments of her speeches concerns the language that she used. Because her first language was Dutch, and she did not learn English until she was nine or so, it is difficult to judge her language and accent. She may have spoken with a Germanic accent, but she may also have acquired some southern Black dialect from fellow slaves. However, there is little or no proof of this background in reports of her speaking. Truth did not approve of those who transcribed her speeches in a thick dialect. In her only remaining scrapbook, a fragment of an article in the Kalamazoo Telegraph that she kept states: Sojoumer also prides herself on a fairly correct English, which is in all senses a foreign tongue to her, she having spent her early years among people speaking "Low Dutch." People who report her often exaggerate her expressions, putting into her mouth the most marked southern dialect, which Sojoumer feels is rather taking an unfair advantage of her. (1) Given such strong indications of her unusual language background, the most extreme "negroisms" attributed to her have been removed in this chapter. - eBook - PDF

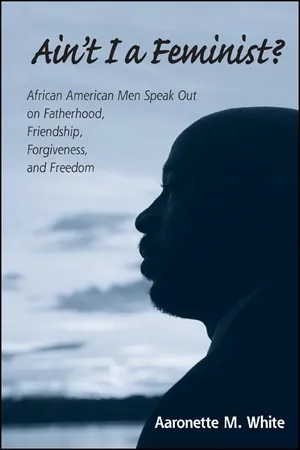

Ain't I a Feminist?

African American Men Speak Out on Fatherhood, Friendship, Forgiveness, and Freedom

- Aaronette M. White(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- SUNY Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 2 Biographical Sketches The Sons of Sojourner Truth S ojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” speech was a response to jeers from White men, who often yelled during her antislavery public speeches, “We don’t believe you’re really a woman!” Those insults also came from some White women’s rights activists, who felt it was beneath them to listen to a Black woman speak publicly about the rights of Black women to vote and to be free. 1 Isabella Baumfree, as she was called before she took the name Sojourner Truth, through her famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech shared her personal “truth” about slavery and chal- lenged White men, White women, and Black men to beware of exclu- sionary practices in the name of social justice regarding Black women’s right to vote. I consider feminist Black men her sons, continuing her legacy. Just as Sojourner Truth argued that she was a woman, even though she was not White, I argue that each man in this study is a femi- nist, although he is not female. Most important, Sojourner refused to pri- oritize race over gender when she stated in one of her speeches: There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad. 2 Sojourner Truth aptly understood that most Black men and White women of her day were insensitive to the plight of Black women, who also desper- ately needed the right to vote. “An acute observer, Truth recognized the 12 patriarchal insistence of black male abolitionists to assert their right to vote over women of either race and the separate resolve of white women suffragists to assert their right to vote over black people of either sex,” 3 notes African American feminist political scientist Evelyn Simien. - Carolyn M. Jones Medine, Ibigbolade S. Aderibigbe, Carolyn M. Jones Medine, Ibigbolade S. Aderibigbe, Kenneth A. Loparo, Hans D Seibel(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

One can follow the Trail of Sojourner Truth in Ulster County, New York, where she was a slave and claimed her freedom, walking away from her master; that location also houses a library. Truth emerges as a key figure in African American thought, but her most famous texts, her Narrative and her “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” speech, because she was unable to read or write, are collaboratively written, seeming to give over her agency to other, white women writers. Indeed, her Narrative is in two parts—the narrative proper, written with Olive Gilbert, and a Book of Life, assembled by Frances Titus, a collec- tion of letters to and articles about Sojourner Truth, as well as her autograph book. While we might worry that Truth’s identity may be misrepresented, at least, and appropriated, at best—her voice is so determined that we never can find a “real” Sojourner Truth. I want to suggest that the choral, collaborative, and multi-vocal voice serves the purpose of integrating the singular voice into community—and, for Truth, those communities were multiple—and preserving voices that would be oth- erwise lost, as we see in the opposite example of W. E. B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk. If DuBois is the controlling narrative voice, Truth seems to be the controlled narrative voice. While some of her biographers suggest that this means that the “real” Sojourner Truth, finally, was erased in the service of others, I want to suggest that she emerges as a curious, moving center, an outsider—a true sojourner—whose call elicited and still elicits creative response. To examine this positionality, we will look at two key pieces of Sojourner Truth’s life: her “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” speech and her conversion from the Narrative. Women in the African Diaspora 137 “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” Sojourner Truth’s “Ar’n’t I a Woman” speech has a complex transmission history.- eBook - PDF

Sojourner Truth as Orator

Wit, Story, and Song

- Suzanne P. Fitch, Roseann Mandziuk(Authors)

- 1997(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

79. "Sojourner Truth on Dress," New York Tribune 4 Nov. 1870: 4. 80. "Sojoumer Truth: The Fashions," Narrative 243-45. 81. Stanton 927. 82. Stone 252. 83. "Sojourner Truth,"(James Dugdale Report) National Anti-Slavery Standard 4 July 1863: 3. 84. "Sojourner Truth," (James Dugdale Report) National Anti-Slavery Standard 4 July 1863: 3. This page intentionally left blank 4 Storyteller and Songstress Any understanding of the rhetorical power of Sojourner Truth must begin with an appreciation of her tremendous appeal and the hold that she commanded over audiences. For example, the report in the National Anti-Slavery Standard of her 1863 speech to the State Sabbath School Convention in Battle Creek, Michigan, provided an impressive indication of her power and popularity: Rev. T. W. Jones arose, and addressing the moderator, said that the speaker was "Sojourner Truth". This was enough: five hundred persons were instantly on their feet, prepared to give the most earnest and respectful attention to her who was once but a slave. Had Henry Ward Beecher, or any other such renowned man's name been men- tioned, it is doubtful whether it would have produced the electrical effect on the audience that her name did. 1 Most accounts of Truth's speaking indicated similar reactions. Her rhetoric commanded the attention of audiences and the respect of her contemporaries, primarily because it was so accessible and simple, yet clever and insightful. Truth's personal style was marked by an interweaving of small anecdotes, tales from her personal experiences, familiar biblical references, and homespun, commonsense arguments. These basic aspects of her rhetoric combined to form a substantial, persuasive framework. From such varied sources she intertwined the tale of her life with the tale of her people. Coupled with her powerful physi- cal presence and simple, Quaker-like dress, the result was a rhetorical narrative that both entertained and persuaded. - eBook - PDF

Turn the Pulpit Loose

Two Centuries of American Women Evangelists

- P. Pope-Levison(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

But they found they were mistaken, and that their fears were groundless; for, before they could well recover from their surprise, every rioter was gone, and not one was left on the grounds, or seen there again during the meeting. Sojourner was informed that as her audience reached the main road, some distance from the tents, a few of the rebellious spirits refused to go on, and proposed returning; but their leaders said, “No—we have promised to leave—all promised, and we must go, all go, and you shall none of you return again.” 25 Several months after she went east, as the weather turned colder, Sojourner settled into a utopian community, the Northampton Association for Education and Industry, whose purpose was to transcend class, race, and gender distinctions. The community lasted less than five years because the manufacture of silk, its sole economic base, was not profitable. Nevertheless, many reform-minded, influential people visited Northampton, such as abolitionist leaders, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, and through these connections, Sojourner began speaking on the antislavery lecture circuit. On Women Sojourner also met women’s rights activists at Northampton, and in 1851, she attended the Ohio Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, where she gave her infamous “Ain’t I A Woman” speech. The speech has survived in several versions, the most popular and well known of which was written twelve years after the event by Frances Dana Gage, chair of the Akron Convention. Gage undoubtedly embellished and exaggerated the speech, but it is her version Sojourner Truth 55 that has survived for posterity. 26 Recent historians convincingly argue that the most reliable account was written immediately after the event by Marius Robinson, who was the secretary of the convention and a friend of Sojourner’s. Sojourner frequently stayed with Robinson and his wife for sev- eral weeks at a time, and Robinson knew well her manner of talking. - eBook - PDF

The Strange Career of the Black Athlete

African Americans and Sports

- Russell T. Wigginton(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

5 R “SHE’S DONE MORE FOR HER COUNTRY THAN WHAT THE U.S. COULD HAVE PAID HER FOR”: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AND SPORTS In 1851, in the small town of Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth took her turn on the stage to give her speech at the Women’s Rights convention. Although she was greeted rather unpleasantly with boos and hisses, Truth seemed undisturbed and quite focused on making the points that she had come to deliver. In fact, this illiterate, itinerant ex-slave demonstrated unwavering poise as she began by saying: Well, chilern, whar dar is so much racket der must be something out of kilter. I tink dat ‘twixt de niggers of de Souf and de women at de Norf all a talking’ ‘bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. 1 Truth went on in her speech to share a few personal experiences that captured the disrespect and disdain that was protocol for how African Americans women experienced life. In each example, Truth, in her improper but articulate speak, asked the question, “and ar’n’t I a woman?” 2 Truth’s genius, courage, and pioneering spirit made her the first recognized African American woman suffragist. As well, Truth’s speech publicized the nonsensical and hypocritical norms of the United States’ white, male- dominated culture. As has been demonstrated, American culture has had tremendous impact on the mores in the sporting world. Thus, looking through the lens of sports at how such simple words spoken by Sojourner Truth in the mid-nineteenth century rang true then and continue to have relevance today is the focus of this particular chapter. 88 The Strange Career of the Black Athlete Although there has been a significant increase in the amount and quality of scholarship on black women athletes in the last 10 to 15 years, it is still described most accurately as a trickle rather than an outpouring. - eBook - PDF

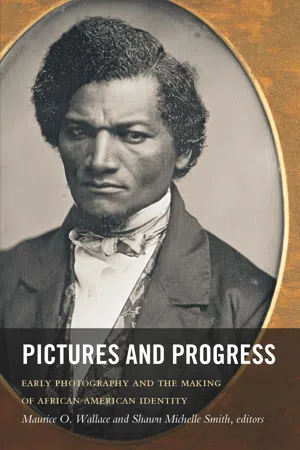

Pictures and Progress

Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity

- Maurice O. Wallace, Shawn Michelle Smith, Maurice O. Wallace, Shawn Michelle Smith(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

THREE Shadow and Substance Sojourner Truth in Black and whitE Augusta Rohrbach An illiterate former slave, Sojourner Truth left no written record of her own according to standard definitions of authorship. Yet, during her life-time and beyond, Truth forged an iconic identity in a print-laden world through various “publications.” Chief among them were the cartes de visite she sold, in various forms. Emblazoned with the slogan, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” Truth’s photographs remain the most stable records of her efforts to intervene in a culture shifting from speech to writ-ing and from image to text. Reading those pictures—and the variety of uses she put them to—offers us a glimpse into Truth’s self-fashioning unlike any other record associated with her. The examples of what might seem to be ephemeral photographic evidence expose the hand of the “author” and re-veal the deliberately unwritten story of Truth’s greatest accomplishment: establishing herself as a historical entity and an international icon. Before undertaking the careful construction of her image, however, Truth had already intervened in the conventions of print culture through another means. Though she published her own narrative in 1850, with the help of Olive Gilbert as amanuensis, her fame stems from a speech she made in 1851 at an Akron, Ohio, women’s rights rally. Popularly known as the “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” speech, the print history of this address epitomizes the difficulty scholars have had pinning down its charismatic speaker. Two versions of the speech exist, bearing little resemblance to each other, cast-ing doubt on the record of this defining oration.1 In the case of both the speech in 1851 and the cartes de visite of 1864, 84 AUGUSTA ROHRBACH timing is everything. Set into the context of her developing reputation, these acts function as reactions against and interventions in a dominant white culture’s production of her image. - eBook - ePub

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. (Susan Brownell) Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, (Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

Gage said: I have but little to say because it is almost two o'clock, and hungry and weary people are not good listeners to speeches. I shall confine my remarks therefore to one special point brought up this morning and not fully discussed. Sojourner Truth gave us the whole truth in about fifteen words: "If I am responsible for the deeds done in my body, the same as the white male citizen is, I have a right to all the rights he has to help him through the world." I shall speak for the slave woman at the South. I have always lifted my voice for her when I have spoken at all. I will not give up the slave woman into the hands of man, to do with her as he pleases hereafter. I know the plea that was made to me in South Carolina, and down in the Mississippi valley. They said, "You give us a nominal freedom, but you leave us under the heel of our husbands, who are tyrants almost equal to our masters." The former slave man of the South has learned his lesson of oppression and wrong of his old master; and they think the wife has no right to her earnings. I was often asked, "Why don't the Government pay my wife's earnings to me?" When acting for the Freedman's Aid Society, the orders came to us to compel marriage, or to separate families. I issued the order as I was bound to do, as General Superintendent of the Fourth Division under General Saxton. The men came to me and wanted to be married, because they said if they were married in the church, they could manage the women, and take care of their money, but if they were not married in the church the women took their own wages and did just as they had a mind to. But the women came to me and said, "We don't want to be married in the church, because if we are our husbands will whip the children and whip us if they want to; they are no better than old masters." The biggest quarrel I had with the colored people down there, was with a plantation man because I would not furnish a nurse for his child

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.