History

Square Deal

The Square Deal was a domestic program introduced by President Theodore Roosevelt in the early 20th century. It aimed to strike a balance between the interests of labor, business, and the public by promoting fair treatment, conservation of natural resources, and regulation of big business. The Square Deal sought to address social and economic inequalities through progressive reforms.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

4 Key excerpts on "Square Deal"

- eBook - ePub

America in the Age of the Titans

The Progressive Era and World War I

- Sean Dennis Cashman(Author)

- 1988(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER TWO Bear Necessities: Theodore Roosevelt and the Square DealTHEODORE ROOSEVELT’S accession to the presidency, albeit in tragic circumstances, signaled the end of the Gilded Age of 1865-1901 and the opening of the Progressive Era of 1901-17. It seemed that progress, whether in inventions, industry, or democratic government, was the key to modern America. It was an insistence on progress that underlay the reform movement we call Progressivism and that was at its zenith in the early twentieth century. Reformers tried to bring rational order to politics, industry, and cities as the United States was being transformed from a rural to an urban and industrial economy. Progressives thought that they could correct such dislocations and evils as: excessive concentration of economic power in a few monopolies; wasteful consumption of the nation’s resources; corrupt party machines; sweatshops, child labor, and overcrowded slums.The first centers of the progressive movement in the 1890s were the large cities of the Northeast and Midwest and the mainly agrarian communities of the Midwest and parts of the South. After what novelist Theodore Dreiser called “the furnace stage” in the making of major cities, an optimistic and energetic middle class first moved to improve facilities, remodel government, and enhance its social status. The Progressive movement then moved to state government with the election of reform governors like Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin (1901-6), and gained a national voice during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency (1901-9), scoring legislation in his second administration. It concentrated its reform ideas during the disappointing presidency of William Howard Taft (1909-13), formed a third political party in 1912, and achieved several fundamental federal reforms during the first administration of Woodrow Wilson (1913-17). It was divided by Wilson’s policies during World War I and resurfaced briefly in the elections of 1924 when La Follette stood as a third party presidential candidate. - eBook - PDF

Progressive Challenges to the American Constitution

A New Republic

- Bradley C. S. Watson(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

As president, Roosevelt had put his “New Nationalism” into action, first, by giving to “men of special ability, train- ing, and eminence a better opportunity to serve the public,” and second, by restoring the Republican Party to the high moral purpose it had pursued under Lincoln. 7 Still, not even TR was immune to criticism. The “Square Deal,” the phrase Roosevelt had employed as president to describe his program, was nothing more than an updated version of the Jeffersonian principle of “equal rights for all, special privileges for none.” As such, it denied to American democracy any more constructive purpose than eliminat- ing unfair privileges and as such, turned the district attorney into the model citizen. In Croly’s view, it was not enough to enforce the rules of the game; the game itself had to be changed. Even so, Roosevelt “builded better than he knew.” His program was both “more novel and more radical” in two respects: first, it implied a view of democracy that departed from the Jeffersonian principle of equal rights, and second, despite his insistence on playing by the rules, Roosevelt’s policies seemed to point toward a revision of those very rules. However, since “candid and consistent thinking” was not Roosevelt’s strong suit, Croly doubted that Roosevelt fathomed the full implica- tions of his actions. The “prophet of the Strenuous Life” had allowed his will to dominate his intellect, destroying the fine balance between these two faculties by his “sheer exuberance of moral energy.” As Croly portrayed him, Roosevelt was more than a manly man; he was Thor, “wielding with power and effect a sledge-hammer in the cause of national righteousness.” 8 Although the hammer blows were instinctively well-aimed, they cried out for a superintending intelligence that would give direction to his mighty efforts. - eBook - PDF

The Brief American Pageant

A History of the Republic

- David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl, , David Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, Mel Piehl(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Starry-eyed Socialists dreamed of being in the White House within eight years. Taft went on to a fruitful old age. He taught law for eight pleasant years at Yale University and in 1921 became chief justice of the Supreme Court—a job for which he was far more happily suited than the presidency. The progressive movement of the early twentieth century became the greatest American reform crusade since aboli-tionism. Inaugurated by Populists, socialists, social gospelers, female reformers, and muckraking journalists, progressivism became a widely popular effort to strengthen government’s power to correct the many social and economic problems associated with industrialization and urbanization. Progressivism began at the city and state level, where it initially focused on “good government” political reforms to corral corrupt bosses. It then turned to correcting a host of social and economic evils that seemed to require national action by the federal government. Women played an espe-cially critical role in galvanizing progressive social concern. Seeing involvement in such issues as reforming child labor, poor tenement housing, and consumer causes as a natural extension of their traditional roles as wives and mothers, female activists brought significant changes in both law and public attitudes in these areas. At the national level, Roosevelt’s Square Deal vigorously deployed the federal government to promote the public inter-est and mediate conflicts between labor interests on the one hand and the corporate trusts on the other. Rooseveltian pro-gressivism also inspired attention to consumer and environ-mental concerns. Conservation became an important public crusade under Roosevelt, although sharp disagreements divided wilderness “preservationists” from moderate conser-vationists such as Roosevelt who favored the “multiple use” of nature. CHAPTER SUMMARY Copyright 201 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. - No longer available |Learn more

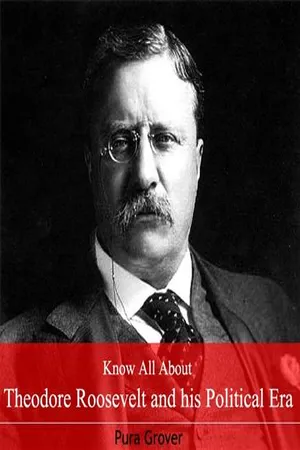

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

Domestic policy Progressivism Determined to create what he called a Square Deal between business and labor, Roosevelt pushed several pieces of progressive legislation through Congress. Progressivism in the United States was the most powerful political force of the day, and in the first dozen years of the century Roosevelt was its most articulate spokesman. Progressivism meant expertise, and the use of science, engineering, technology and the new social sciences to identify the nation's problems, and identify ways to eliminate waste and inefficiency and to promote modernization. Roosevelt, trained as a biologist, identified himself and his programs with the mystique of science. The other side of Progressivism was a burning hatred of corruption and a fear of powerful and dangerous forces, such as political machines, the corrupt segment of labor unions and especially the new large corporations — called trusts — which seemed to have emerged overnight. Roosevelt, the former deputy sheriff on the Dakota frontier, and police commissioner of New York City, knew evil when he saw it and was dedicated to destroying it. Roosevelt's moralistic determination set the tone of national politics. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902 Coal miners in Hazleton, PA. 1905 The Coal Strike of 1902 was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania. The strike threatened to shut down the winter fuel supply to all major cities (homes and apartments were heated with anthracite or hard coal because it had higher heat value and less smoke than soft or bituminous coal). President Theodore Roosevelt became involved and set up a fact-finding commission that suspended the strike. The strike never resumed, as the miners received more pay for fewer hours; the owners got a higher price for coal, and did not recognize

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.