History

Third Reich

The Third Reich refers to the Nazi regime in Germany from 1933 to 1945, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. It was characterized by totalitarian control, aggressive expansionism, and the implementation of racist policies, including the Holocaust. The term "Third Reich" reflects the Nazi ideology of creating a new, powerful German empire, following the First Reich (the Holy Roman Empire) and the Second Reich (the German Empire).

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Third Reich"

- eBook - PDF

The Fourth Reich

The Specter of Nazism from World War II to the Present

- Gavriel D. Rosenfeld(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Avoiding the phrase in the hope of demythologizing it, moreover, may also reduce our capacity to understand its original propagandistic function. To be sure, referring to the Third Reich naively, without any awareness of its fraught history, is also inadvisable. But employing it in a scholarly sense does not mean endorsing it. Given the politics of usage that surrounds the concept, the Third Reich is best understood by historicizing it within the larger context of German history. The easiest place to begin is with the term “Reich” 20 / The Fourth Reich itself. Translated into English, the German word “Reich” broadly means “realm,” but it is most often translated as “empire” or “king- dom.” The term is thus both a spatial designation and a signifier for a political formation. In the context of German history, the term “Reich” has been applied to several states that have existed over the span of a thousand years. The first was the Holy Roman Empire, usually dated as lasting from its founding by the Frankish king, Charlemagne, in the year 800 (or, in other accounts, by his Saxon successor, Otto I, in 962) until its dissolution by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806. The second was the Wilhelmine Empire, known as the Kaiserreich, which lasted from 1871 until its collapse in 1918. The third was the Nazi regime. This tripartite definition regularly appears in surveys of German history. However, the definition is incomplete, as it reduces the term “Reich” to a mere political designation. In truth, the idea of the Reich also has profound spiritual – indeed mystical – connotations. These connotations are deeply rooted in Christian theology, particularly in the chiliastic idea of God’s even- tual Kingdom (Reich) on Earth. According to the latter chapters of the Book of Revelation, this kingdom would take the form of a thousand- year period of peace (known as the “millennium”) that would both precede and follow Jesus’s battle with Satan. - eBook - ePub

West Germany

A Contemporary History

- Michael Balfour(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

4 The Third Reich, 1933–1945The Totalitarian State

Part of the Nazi technique lay in never allowing their competitors a letup or the German people a dull moment. No sooner was Hitler installed as Chancellor than another election was announced – the third in eight months. The propaganda machine, which now had full access to the radio system, was turned on in full strength (subject only to the discovery that Hitler was a poor speaker in the studio). The storm-troopers, 40,000 of whom were taken on as auxiliaries by the Prussian police, were let loose in the streets. We are unlikely ever to know for certain how the Reichstag building was set on fire on the night of 27 February; it is perfectly possible that the half-witted Dutchman found inside really did the job on his own. What is beyond dispute is the energy with which the Nazis exploited the supposed Communist conspiracy. On the following day, Hindenburg was induced to sign an emergency decree suspending many of the vital personal liberties, authorising the Reich Government to interfere in the Länder and making death the penalty for a number of crimes.But when the Election came on 5 March, the result was far from being the triumph which was represented. 13 million out of 32 million voted for democratic parties and the Communists lost no more than 19 seats; the Nazis only won 43.7 per cent of the poll and were left relying on the Nationalists for a majority in the Reichstag. When it met, the Deputies were presented with an Enabling Bill which would for five years authorise the Chancellor, without reference to the President and irrespective of what might be said in the Constitution, to issue laws on any subject he chose. Only one Deputy (a Social Democrat) spoke against it and only Social Democrats voted against it (the Communists having already been proscribed). Hitler thus made himself dictator by legal methods while the Reichstag abdicated its functions and henceforward only met at intervals to be harangued. - eBook - ePub

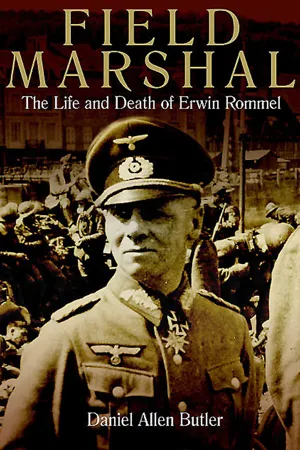

Field Marshal

The Life and Death of Erwin Rommel

- Daniel Allen Butler(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Casemate(Publisher)

CHAPTER FOUR THE Third ReichPower resides only where men believe it resides. . . a shadow on the wall, yet shadows can kill. And ofttimes a very small man can cast a very large shadow.—GEORGE R.R. MARTINT he rise of the Nazi Party, its leader and his apostles from wide-eyed fanatical splinter party to the absolute masters of Germany is the most thoroughly chronicled political phenomenon of the twentieth century. Explanations of and apologists for how it came about are rife, and there is hardly room, let alone need, for yet another accounting of those events, although it should always be borne in mind that the phenomenon which was Adolf Hitler came about not through a coincidence and confluence of exceptional economic, social, and political circumstances which will likely never again recur, but rather because a sufficiently ruthless individual possessing a genuine will to power—a true Nitzschean Wille zur Macht—can always exploit a people who, feeling betrayed by their institutions and bereft of leadership, will be willing to embrace a demogogue who offers what appear to be answers and solutions to their fears and problems.For Erwin Rommel, the Nazis were fundamentally irrelevant to him, personally and professionally, until January 30, 1933; at noon that day, Adolf Hitler took the oath of office as chancellor of the German Republic. Prior to that moment, the irrelevance of both Hitler and the Nazis to Rommel was not due to any postured disdain for or inherent disapproval of the National Socialists or their leader; instead it was the product of Rommel’s dedication to being the perfect non-political Reichswehr officer, as conceived of by von Seeckt.This is not to say that Rommel was unaware of Hitler, or that he held no political views or opinions whatsoever; either idea is patently absurd. But until Hitler became chancellor, he was only the leader of a political party, one that was, admittedly, rising and which was, month by month, exercising greater and greater influence over the German people as well as the government’s policies; but Hitler remained a party leader without office nonetheless. Elevation to the chancellorship meant that, at whatever remove it might be, Adolf Hitler would now be an influence on Erwin Rommel’s career and life. If the rumors were true, and Hitler was prepared to combine the office of the Reichskanzler with that of the Reichspräsident - eBook - ePub

- Michael Balfour(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

4 THE Third Reich: 1933–1945

THE TOTALITARIAN STATE

Part of the Nazi technique lay in never allowing their competitors a let-up or the German people a dull moment. No sooner was Hitler installed as Chancellor than another election was announced—the third in eight months. The propaganda machine, which now had full access to the radio system, was turned on in full strength (subject only to the discovery that Hitler was a poor speaker in the studio). The Storm-Troopers, 40,000 of whom were taken on as auxiliaries by the Prussian police, were let loose in the streets. We are unlikely ever to know for certain how the Reichstag building was set on fire on the night of 27 February; it is perfectly possible that the half-witted Dutchman found inside really did the job on his own. What is beyond dispute is the energy with which the Nazis exploited the supposed Communist conspiracy. On the following day, Hindenburg was induced to sign an emergency decree suspending many of the vital personal liberties, authorizing the Reich Government to interfere in the Länder and making death the penalty for a number of crimes.But when the election came on 5 March, the result was far from being the triumph which was represented: 13 million out of 32 million voted for democratic parties and the Communists lost no more than nineteen seats; the Nazis won only 43.7 per cent of the poll and were left relying on the Nationalists for a majority in the Reichstag. When it met, the Deputies were presented with an Enabling Bill which would for five years authorize the Chancellor, without reference to the President and irrespective of what might be said in the Constitution, to issue laws on any subject he chose. Only one Deputy (a Social Democrat) spoke against it and only Social Democrats voted against it (the Communists having already been proscribed). Hitler thus made himself dictator by legal methods while the Reichstag abdicated its functions and henceforward met only at intervals to be harangued. - eBook - PDF

- D. Stone(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Large, Where Ghosts Walked: Munich’s Road to the Third Reich (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997). 39 A. Tyrell, Führer befiehl . . . Selbstzeugnisse aus der ‘Kampfzeit’ der NSDAP (Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag, 1969) and W. Horn, Führerideologie und Parteiorganisation in der NSDAP (1919–1933) (Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag, 1972). See also J. Nyomarkay, Charisma and Factionalism in the Nazi Party (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1967) and D. Orlow, The History of the Nazi Party Vol. 1: 1919–1933 (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1969). 40 The classic work remains K.D. Bracher, Die Auflösung der Weimarer Republik: Eine Studie zum Problem des Machtverfalls in der Demokratie (Stuttgart: Ring Verlag, 1955). The most outstanding recent studies are G. Schulz, Zwischen Demokratie und Diktatur: Verfassungspolitik und Reichsreform in der Weimarer Republik. Vol. 3: Von Brüning zu Hitler. Der Wandel des politischen Systems in Deutschland (Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1992); H.A. Winkler, Weimar 1918–1933: Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Demokratie (Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck, 1993); H. Mommsen, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). 41 J. Falter, Hitlers Wähler (Munich: C.H. Beck, 1991). 42 On this period see, in addition to those works mentioned in note 40 above, H.A. Winkler, ed., Die deutsche Staatskrise 1930–1933: Handlungsspielräume und Alternativen (Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1992). 43 H.A. Turner, Hitler’s Thirty Days to Power: January 1933 (London: Bloomsbury, 1996). 44 Among the most useful general works on the Third Reich are K.D. Bracher, The German Dictatorship (London: Penguin Books, 1973); M. Broszat, The Hitler State: the Foundation and Development of the Internal Structure (London: Longman, 1981); K. Hildebrand, The Third Reich (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1984); H.-U. Thamer, Verführung und Gewalt: Deutschland 1933–1945 (Berlin: Siedler, 1986); N. - eBook - ePub

Hitler and Nazi Germany

A History

- Jackson J. Spielvogel, David Redles(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In our survey of the Nazis’ attempt to establish a total state from 1933 to 1939, we have repeatedly witnessed the mixture of old and new that prevailed in the Nazi system, whether in the organization of the government, the judiciary, the military, or the economic sphere. The new Nazi structure was characterized by a dualism that often created considerable confusion about lines of authority. But Hitler and the Nazi leadership were clear about the underlying goal of establishing a national community that would be unified and mobilized for war so that Hitler could pursue his expansionary aims. In 1937 and 1938, Hitler made changes in the domestic sphere that corresponded to his more radical foreign policy shift to possible military adventures. Until then, the government had been based on cooperation with old-line conservatives such as Schacht in the Ministry of Economics and von Neurath in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In November 1937, Schacht resigned over differences with Göring’s handling of the war economy and was replaced by the ardent Nazi Walther Funk. Early in 1938 the conservative Neurath was replaced by Joachim von Ribbentrop, ill-qualified but totally dedicated to Hitler’s grandiose plans. Military leadership was also shifted to give Hitler more control. One is left with the strong impression that the goal of these changes was to make it easier for Hitler to realize his dreams in the foreign-policy and military spheres. Before we examine these goals and their results, though, we need to look in more detail at the man whose ideas and actions have dominated this story.Suggestions for Further Reading

The basic study of Nazi rule is Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (New York, 2005). See also Thomas Childers, The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (New York, 2017); and Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New Histor y (New York, 2000); The Nazi administration of the state is examined in Martin Broszat, The Hitler State: The Foundations and Development of the Internal Structure of the Third Reich (New York, 1981); and Ernst Fraenkel, The Dual State (New York, 1941). An interesting reappraisal of Fraenkel’s notion of the dual state is Jens Meierhenrich, The Remnants of the Rechtsstaat: An Ethnography of Nazi Law (Oxford, 2018). Other studies include Norbert Frei, National Socialist Rule in Germany: The Führer State 1933–1945 , trans. Simon B. Steyne (Oxford, 1993); Edward N. Peterson, The Limits of Hitler’s Power (Princeton, NJ, 1970); Peter Hoffmann, Hitler’s Personal Security (London, 1979); and a collection of essays edited by Jeremy Noakes, Government, Party and People in Nazi Germany (Exeter, 1980). Jane Caplan’s Government Without Administration. State and Civil Service in Weimar and Nazi Germany (Oxford, 1988) analyzes the effect of the Nazis on the bureaucracy. The charismatic base of Hitler’s power is examined in Ian Kershaw, Hitler (London and New York, 1991); and Martin Kitchen, The Third Reich: Charisma and Community - Casey Anderson, Joshua Horowitz(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of Michigan Press(Publisher)

This promoted an ethnic de‹nition of nationhood which could easily slide over (though it by no means always did so) into forms of racism.” In the 1912 Reichstag elections, the Social Democratic Party, devoted to a Marxist agenda, was the largest party. In its path stood the collective forces of “a highly aggressive integral nationalism aiming to destroy Marxist socialism.” After the war, Hitler harnessed this nation-alism to exploit “the belief that pluralism was somehow unnatural or unhealthy in a society” and destroyed his enemies, including Jews and Social Democrats. 15 Germany entered World War I following the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, with wide-spread support from most sectors of society. 16 The war caused severe hardship for the German people. About 2,000,000 German soldiers were killed, and 5,000,000 more were wounded. By 1917, food shortages in Germany caused malnutrition on a large scale, killing 750,000 people. Coal shortages left people cold all winter. These developments led to in-creased social tension and worker strikes. 17 War efforts in the spring of 1918 had gone well, but disastrous reversals, hidden from the people and even from the Reichstag, forced the German government to seek a peace treaty in October. At the armistice, the army was outside German territory, but the situation was hopeless. In replying to the German request for peace in October, President Woodrow Wilson noted that autocratic monarchs and military rulers posed an impediment to negotiations. By November 7, the Bavarian monarchy had crumbled, and the kaiser abdicated two days later, forced out by a “groundswell of popular demand for radical change.” 18 The the rise of the Third Reich 143 masses wanted democracy, yet there was no agreement on what that meant in practice.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.