Physics

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner was an Austrian physicist who made significant contributions to the field of nuclear physics. She was part of the team that discovered nuclear fission, which led to the development of nuclear energy and the atomic bomb. Despite facing discrimination as a woman in a male-dominated field, Meitner's work paved the way for future generations of female scientists.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

4 Key excerpts on "Lise Meitner"

- eBook - ePub

- Arne Hessenbruch(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1878–1968 Austrian physicistBerninger, E.H., “Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann in Berlin wird die Kernspaltung entdeckt”, in Berlinische Lebensbilder: Naturwissenschaftler, edited by W. Treue and G. Hildebrandt, Berlin: Colloquium, 1987Ernst, Sabine (ed.), Lise Meitner an Otto Hahn: Briefe aus den ]ahren 1912 bis 1924, Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1992Feyl, Renate, “Lise Meitner”, in her Der lautlose Aufbruch: Frauen in der Wissenschaft, Berlin: Neues Leben, 1981Frisch, O.R., “Lise Meitner”, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 16 (1970): 405–420Herneck, Friedrich, “Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner” in his Bahnbrecher des Atomzeitalters. Grosse Naturforscher von Maxwell bis Heisenberg, Berlin: Morgen, 1965Kerner, Charlotte, Lise: Atomphysikerin: Die Lebensgeschichte der Lise Meitner, Weinheim and Basel: Beltz, 1986Krafft, Fritz, Im Schatten der Sensation: Leben und Wirken von Fritz Strassman, Weinheim: Chemie, 1981, 165ffRife, Patricia, Lise Meitner, Düsseldorf: Claassen, 1990Sime, Ruth Lewin, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996Stolz, Werner, Otto Hahn/Lise Meitner, Leipzig: Teubner, 1983The biographical literature on the outstanding 20th-century physicist, Lise Meitner, can be divided roughly into two parts. The first part consists of mainly older studies that treat her life and work, in a more or less hagiographic manner, in relation to that of her colleague, Otto Hahn. The second part consists of the more recent representations that, strongly influenced by the rise of the feminist movement, try to present Lise Meitner’s biography within the context of women in science. Neither approach does full justice to Meitner, since she was neither a mere “co-worker” of Otto Hahn, nor was she an ambitious suffragette, or even a feminist. - eBook - ePub

- Michael F. L'Annunziata(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

I believe that all young people think about how they would like their lives to develop. When I did so, I always arrived at the conclusion that life need not be easy; what is important is that it not be empty. And this wish I have been granted.Lise Meitner retired in 1960 in Cambridge, England. She continued to lecture and visit friends up to 1964 when she suffered a heart attack after a strenuous trip to the United States. She recovered from the heart attack and the following year was awarded the Enrico Fermi Prize with Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann for contributions to nuclear chemistry and the discovery of nuclear fission. Glenn T. Seaborg, then Chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission went to Cambridge to present her share of the award (Frisch, 1978 ). Lise Meitner died on October 27, 1968. Otto Hahn, after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1945, continued his research on the identification and separation of many radioactive isotopes that arise through fission. He died a few months before Lise Meitner on July 28, 1968 (Nobel Lectures, Chemistry, 1901–1970).LEO SZILARD (1898–1964)

Leo Szilard was born Leo Spitz on February 11, 1898 to an affluent Jewish family in Budapest, Austro-Hungary. The family name was changed to Szilard in 1900. He was one of the world’s greatest thinkers among the physicists of the 20th century. His mind was never idle and was always conceiving new scientific theories and inventions. He is recognized mostly for his pioneering thought and contributions to nuclear physics, his numerous patents of instruments that have revolutionized 20th century nuclear physics, his patent for the atomic bomb and his spearheading of the formation of a program for its development, the design of the first nuclear reactor (with Enrico Fermi), and his efforts to prevent the nuclear arms race after the Second World War. Szilard did not win the Nobel Prize for any of his achievements; however, two of his patents, which were for the design and operation of the cyclotron (Rhodes, 1986 - eBook - ePub

The Madame Curie Complex

The Hidden History of Women in Science

- Julie Des Jardins(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- The Feminist Press at CUNY(Publisher)

Of course none of this explains what happened to Lise Meitner, the theoretical physicist who did indeed come up with the concept of fission. She had been one-half of a thirty-year partnership with chemist Otto Hahn, but she was a Jew and forced to flee Berlin in 1938, leaving her uranium experiments behind for Hahn and his assistant, Fritz Strassman, to run. She settled in Stockholm and, from a distance, remained the “intellectual head” of the group, at least as Strassman described it. That winter Hahn sent her a letter about the results of his latest experiments. He had bombarded uranium with neutrons and produced barium fragments that he couldn’t explain. Meitner figured that the barium was a product of an unknown process and stewed over the problem until she conceived what’s known as fission. Hahn won the Nobel Prize for the discovery in 1944.In dismissing Meitner’s intellectual contributions to his Nobel-winning work, Hahn also dismissed her part in all the knowledge he had acquired to that point. Together they had discovered thorium in 1908 and protactinium in 1917, and together they had conducted studies on nuclear isomerism. When Hahn was conscripted into the German army during World War I, Meitner was left to isolate protactinium on her own, yet she listed him as first author when she reported the discovery. In the case of fission, he did not return the same courtesy, despite the fact that she had been running uranium experiments for four years before fleeing to Sweden. When peers raised the question of her Nobel-deservedness, Hahn called fission a problem of experimental chemistry, not theoretical physics. His scientific arguments were flimsy, but other factors probably contributed to his minimizing her work. Hahn was an iconic figure, a former war hero, whose successful science improved the collective psyche of Germans during World War II. To credit Meitner for his discovery not only would have tarnished his mythic status, but also would have necessitated confronting the persecution of a Jewish woman, thus opening a political Pandora’s box. A recent biographer believes that Hahn and the German establishment thus colluded to keep the box closed.9 - eBook - PDF

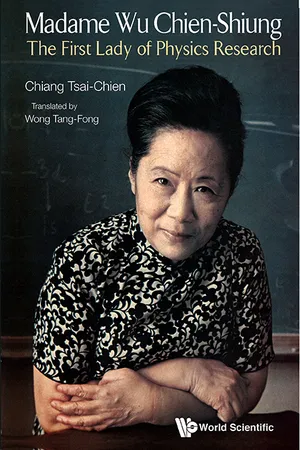

Madame Wu Chien-shiung: The First Lady Of Physics Research

The First Lady of Physics Research

- Tsai-chien Chiang(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

She learned then to drink little water, and avoid using the restroom. She said: “I am well trained.” 14 As another woman physicist, and being in the same research area, Wu praised Meitner highly. She felt that Meitner was a real expert in radioac-tivity, perhaps even more so than Madame Curie. 15 But, in terms of fame, Meitner was far behind. She was a female, and a Jew to boot, and never won the Nobel Prize with its associated glory. Wu felt sorry for Meitner, but she was sort of in the same boat. She still had the feeling that her profound achievements in physics were not fully appreciated according to common gauges. It was clear that three women physicists had made tremendous, and representative, contributions in the 20th century. They were Madame Curie, Meitner, and Wu. In the early 20th century, Madame Curie discovered radium, and greatly advanced the understanding of radioactivity. She and her husband shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Becquerel in 1903. Marie Curie also won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911, for the discovery of radium. With two Nobel Prizes, she was naturally world-famous. Meitner continued with radioactivity research. Her most important work was the identification and understanding of nuclear fission. Although Hahn and his collaborator Strassmann had observed in Berlin in 1938 the strange phenomenon produced by uranium bombarded with neutrons, it was Meitner who correctly identified that it was nuclear fission — the 176 Madame Wu Chien-Shiung Wu in the Rainbow Room. She entertained the famous physicist Lise Meitner there in 1957. splitting of a large nucleus into two. The identification was a result of her many years of research in radioactivity. Before Meitner was exiled to Sweden in 1938, she had been working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Research Institute for more than twenty years. Her contemporaries, such as Einstein, Planck, Bohr, Born, Schrödinger, and M.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.