Politics & International Relations

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism refers to the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on marginalized communities, particularly those of color. It encompasses the siting of polluting industries, waste facilities, and other environmental burdens in these communities, leading to health disparities and economic injustices. This concept highlights the intersection of environmental issues and social inequality, calling for equitable environmental policies and protections.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

9 Key excerpts on "Environmental Racism"

- eBook - ePub

Environmental Justice

International Discourses in Political Economy

- Paul Thompson, Paul Thompson(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

A key insight of this work has been to show that the patterns of inequality that marked economic and social relations in industrialized nations carried forward an expression in environmental conditions as well. Studies of race, class, and gender characteristics of atrisk communities have revealed undeniably unequal environmental threats of those most marginalized by the American political economy. Although limited in scope, studies by U.S. government agencies (notably EPA, 1992; GAO, 1983) have confirmed the general association of communities of color with contaminated areas. Failure to enforce existing antidiscriminatory policies has further added to the evidence of Environmental Racism. As Bullard has commented: “There is a growing movement to turn the current model of environmental protection on its head. It just does not work for many vulnerable populations … Government has been too slow in adopting a prevention framework for these groups.” (1994b: xvi).One of the more damaging revelations from investigations into U.S. environmental injustice was the widespread non-enforcement of laws and regulations (e.g., GAO, 1983; Kratch et al, 1995; and Lavelle and Coyle, 1992). This failure of governance amounted to a political sanctioning of environmental injustice. Race was shown to be a particularly accurate indicator of enforcement failure; with communities of color found to endure disproportionately higher non-enforcement of laws intended to control industrial pollution. Clearly, the explanation lay within the routine practice of social institutions: “Racism plays a key factor in environmental planning and decisionmaking. Indeed, Environmental Racism is reinforced by government, legal, economic, political, and military institutions.” (Bullard, 1993: 17). As Bullard (1993) described, Environmental Racism is a consequence of people of color being excluded from decisionmaking by a system of statecorporate relations that extends from boardrooms of multinational corporations to local zoning boards. Accordingly, the affected communities who responded to these problems were motivated to seek political solutions: “What do grassroots leaders want? These leaders are demanding a shared role in the decisionmaking processes that affect their communities. They want participatory democracy to work for them” (Bullard, 1994b: xvii). - eBook - ePub

Race and Ethnicity in America

From Pre-contact to the Present [4 volumes]

- Russell M. Lawson, Benjamin A. Lawson, Russell M. Lawson, Benjamin A. Lawson, Russell M. Lawson, Benjamin A. Lawson(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Environment 47 (6): 10–23.Bullard, Robert D., ed. 2007. Growing Smarter: Achieving Livable Communities, Environmental Justice, and Regional Equity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Camacho, David E., ed. 1998. Environmental Injustices, Political Struggles: Race, Class, and the Environment. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.Holifield, Ryan. 2001. “Defining Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism.” Urban Geography 22 (1): 78–90.Kirk, Gwyn. 1997. “Ecofeminism and Environmental Justice: Bridges across Gender, Race, and Class.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 18 (2): 2–20.McGurty, Eileen Maura. 1997. “From NIMBY to Civil Rights: The Origins of the Environmental Justice Movement.” Environmental History 2 (3): 301–323.Newkirk, Vann. 2018. “Puerto Rico’s Environmental Catastrophe.” The Atlantic, October 18. Accessed April 28, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/10/an-unsustainable-island/543207/Sandler, Ronald, and Phaedra Pezzullo, eds. 2007. Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: The Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Schlosberg, David. 2013. “Theorising Environmental Justice: The Expanding Sphere of a Discourse.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 37–55.Environmental RacismEnvironmental Racism generally refers to unjust environmental practices that differentially and negatively affect racial minority communities. These practices may include unjustly exposing communities to more environmental and health risks because of disproportionate contact with pollutants, denying access to procedures and processes aimed at preventing exposure to environmental contaminants, or preventing communities of color from obtaining access to environmentally unpolluted spaces and resources. Dismantling practices and policies associated with Environmental Racism is often seen as a specific goal of the environmental justice movement. - eBook - ePub

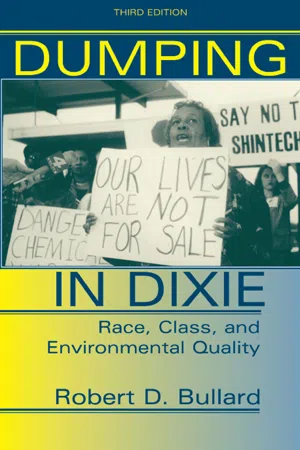

Dumping In Dixie

Race, Class, And Environmental Quality, Third Edition

- Robert D. Bullard(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6Environmental Racism is real; it is not merely an invention of wild-eyed sociologists or radical environmental justice activists. It is just as real as the racism found in the housing industry, educational institutions, the employment arena, and the judicial system. What is Environmental Racism, and how does one recognize it? Environmental Racism refers to any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color. Environmental Racism combines with public policies and industry practices to provide benefits for whites while shifting industry costs to people of color.7 It is reinforced by governmental, legal, economic, political, and military institutions. In a sense, “Every state institution is a racial institution.”8Environmental decision making and policies often mirror the power arrangements of the dominant society and its institutions. A form of illegal “exaction” forces people of color to pay the costs of environmental benefits for the public at large. The question of who pays for and who benefits from the current environmental and industrial policies is central to this analysis of Environmental Racism and other systems of domination and exploitation.Racism influences the likelihood of exposure to environmental and health risks as well as of less access to health care.9 Many U.S. environmental policies distribute the costs in a regressive pattern and provide disproportionate benefits for whites and individuals at the upper end of the education and income scales.10 Numerous studies, dating back to the 1970s, reveal that people-of-color communities have borne greater health and environmental risk burdens than the society at large.11 - eBook - ePub

Polluted Earth

The Science of the Earth's Environment

- Alexander Gates(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

There has been some effort to address this situation. On 5 December 2008, the Asian Development Bank granted a $500 million loan to Indonesia to clean up the river. In November 2011, a river revitalization project began, with an estimated cost of $4 billion over 15 years. The project covers a distance of 112 miles (180 km) along the most polluted part of the river but it barely made a dent in the pollution. In February 2018, the President of Indonesia began a seven‐year project to clean the entire river vowing to achieve clean drinking‐water status. He ordered 7000 soldiers to clean up several sections of the river. However, the lack of money, lack of responsibility coordination, bribes from factory owners to avoid change, and upstream soil erosion from deforestation made this effort ineffective as well. With internet publicity and government enforcement, foreign consultants are joining the effort by helping with upstream changes and launching local awareness and anti‐plastics campaigns. New efforts to remove and recycle plastics appear to be having some success, but the Citarum River is still regarded as the most polluted in the world and has a long way to go to be even marginally acceptable.2.3 Environmental Racism

The environmental justice movement evolved from the concept of Environmental Racism but it expanded to embrace broader issues on an international level. However, the environmental justice movement has retained the original roots of racism in its definition. This makes discerning the two more complicated. Born in the civil rights movement, the concept of environmental justice evolved throughout the 1970s and 1980s, primarily in the United States. The term “Environmental Racism” was first proposed in 1982 by Benjamin Chavis, former director of the United Church of Christ (UCC ) Commission for Racial Justice during the North Carolina PCB dumping and protest incident. As used, it described racial discrimination in environmental policies, enforcement of laws and regulations, targeting of African American communities for toxic waste disposal, sanctioning of poisons and pollutants in African American communities, and the exclusion of African Americans from leadership roles in the environmental and ecology movements.The main factors leading to Environmental Racism are poverty and the lack of affordable land, political power, and mobility for the residents. These factors are largely related to economics making it difficult to absolutely determine whether actions are truly racial or because of economic limitations. Environmental Racism is facilitated by practices that might not seem racist outwardly like suburbanization, gentrification, and decentralization. In suburbanization, however, wealthy and primarily non‐minority residents flee industrially impacted areas for safer, cleaner, and less expensive areas in suburban locations. Gentrification is the opposite process, where wealthy people purchase urban properties and renovate them, gradually converting the area to affluence and thereby forcing out the original residents by driving up property taxes and other costs. - eBook - ePub

From the Ground Up

Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement

- Luke W. Cole, Sheila R. Foster(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

As we have written elsewhere, and as illustrated by the Chester case study, the struggle for environmental justice is primarily a political and economic struggle, with law one facet of that struggle. 30 Understanding Environmental Racism thus requires a conceptual framework that (1) retains a structural view of economic and social forces as they influence discriminatory outcomes, (2) isolates the dynamics within environmental decision-making processes that further contribute to such outcomes, and (3) normatively evaluates social forces and environmental decision-making processes which contribute to disparities in environmental hazard distribution. 31 The Social Structure of Environmental Racism: The Role of Race and Space Let us assume that the current physical distribution of hazardous waste facilities could be attributed to the location of older facilities in neighborhoods that subsequently became populated by poor people of color—that “market dynamics” produced the racially disparate outcomes found in some communities. Even accepting that the siting process is not responsible for all racially disparate outcomes in environmental hazard distribution and that instead the demographics of a given community with a waste facility have changed over time, it is not easy to dismiss the notion that racism or injustice produced the results. If existing racially discriminatory processes in the housing market, for example, contribute to the distribution of environmental hazards, or of people of color, then it is entirely appropriate to call such outcomes unjust, and even racist. 32 In this sense, “Environmental Racism” is not a separate phenomenon at all - eBook - ePub

Polluted Promises

Environmental Racism and the Search for Justice in a Southern Town

- Melissa Checker(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

5This book argues that these startling numbers tell only part of the Environmental Racism story. Going beyond statistics, I look at how Environmental Racism affects real people, every day, on the ground, and how those people struggle against this situation, in part by calling attention to the links between environmental pollution and race. In addition, I show how, while race inflects countless aspects of people’s lives, living in a poor black neighborhood does not necessarily mean all that popular ideology would have it imply—although such ideas can lead to the polluted situations that surround neighborhoods like Hyde Park. Throughout this book, I show just how important definitions are, both for the institutions that use them to assert and maintain privilege and power and for those who work to disrupt such institutions.Defining the Terms of Debate

“Environmental Racism” describes the process that leads to the disproportionate siting of hazardous waste facilities in communities of color. The Reverend Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., a former executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), coined the phrase in his foreword to the United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice’s landmark study, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. In Chavis’s words, Environmental Racism includesracial discrimination in environmental policy-making, enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste disposal and the siting of polluting industries. It is racial discrimination in the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in communities of color. And, it is racial discrimination in the history of excluding people of color from the mainstream environmental groups, decision-making boards, commission, and regulatory bodies.6 - Michael Redclift, Delyse Springett, Michael Redclift, Delyse Springett(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 ). Destabilization is a reality reflected in the environment. The consequences of unstable and collapsing ecosystems are also famines, wars, droughts and floods, lost lives and livelihoods. The combination of economic deprivation and environmental degradation creates increasing poverty and environmental devastation. These downward spirals will transcend gender, class, and race.Environmental justice and sustainability: reshaping economies for equity and ecosystem health

Environmental justice refers to the movement to redress disproportionate adverse impacts on vulnerable populations. Environmental Racism refers to the constellation of public policies that intentionally imposed the risks and harms of development, including waste and toxic pollution, disproportionately on people of color, poor communities, working people, women and children. These policies used these communities as sinks and buffers for the hazardous wastes and pollution by-products of development without allowing them to partake of the wealth generated.The environmental justice movement challenges these policies and practices and the contemporary disparities that are now etched into the landscape of our environment and communities. Environmental justice also challenges the lack of equal access to the benefits of nature and environmental experiences on the part of poor communities and communities of color. These benefits include physical and psychological health, the ability to support one’s life and family, the ability to practice spirituality, human autonomy including family planning, dignity and virtue.Justice and the environment

Sustainability will require us to confront the damage to our ecosystems caused by our choice of development modality. Slavery, genocide, colonialism, industrialism, and exploitation of limited natural resources are part of those development choices. Sustainability will require us to address disparities that exist because of this development model and its history, and revisit deliberate public policy decisions to sacrifice certain groups and communities for development in the quest for a better life for the majority.- eBook - ePub

Environmental Justice

Key Issues

- Brendan Coolsaet, Brendan Coolsaet(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Justice and social policy, 128. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.Blais, Lynn E. 1996. Environmental Racism reconsidered. North Carolina Law Review 75: 75–148.Bravo, Mercedes A., Rebecca Anthopolos, Michelle L. Bell, and Marie Lynn Miranda. 2016. Racial isolation and exposure to airborne particulate matter and ozone in understudied US populations: Environmental justice applications of downscaled numerical model output. Environment International 92–93: 247–255.Cagle, Susie. 2019. Richmond v Chevron: The California city taking on its most powerful polluter. The Guardian, Oct. 9. www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/09/richmond-chevron-california-city-polluter-fossil-fuelCivil Rights Act, Title VI, 42. 1964. U.S.C. §§ 2001e-1 to -17.Cole, Luke W. and Sheila R. Foster. 2001. From the ground up: Environmental Racism and the rise of the environmental justice movement. New York: New York University Press.Davenport, Coral. 2016. Senate approves funding for flint water crisis. The New York Times, Sept. 15.DeFur, P.L., G.W. Evans, E.A. Hubal, A.D. Kyle, R. Morello-Frosch, and D.A. Williams. 2007. Vulnerability as a function of individual and group resources in cumulative risk assessment. Environmental Health Perspectives 115: 817–824.Del Real, Jose A. 2019. The grow the nation’s food, but they can’t drink the water. The New York Times, May 21.Environmental Protection Agency. 1996. Nondiscrimination in programs receiving federal Assistance from the environmental protection agency. Code of Federal Regulations 40: §7.35(b)-(c).Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. EJ 2020 action agenda: The U.S. EPA’s environmental justice strategic plan for 2016–2020. www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/052216_ej_2020_strategic_plan_final_0.pdfEnvironmental Protection Agency. n.d. EJ screen: Environmental justice screening and mapping tool. www.epa.gov/ejscreen .Fahsbender, John J. 1996. An analytical approach to defining the affected neighborhood in the environmental justice context. NYU Environmental Law Journal - eBook - ePub

Traditions and Trends in Global Environmental Politics

International Relations and the Earth

- Olaf Corry, Hayley Stevenson, Olaf Corry, Hayley Stevenson(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

However, in recent times, the political assumptions and ethical foundations upon which such institutions are built have been heavily criticised. Not least for insufficiently challenging global power inequalities (procedural justice) and for producing governance arrangements that do not protect – let alone improve the position of – already vulnerable people and natural environments (Gardiner 2011; Okereke 2007). For example, in the case of international biodiversity conservation and the protected land disputes it gives rise to, local livelihoods and non-economic valuations of nature have frequently been shown to come second to global capitalist priorities and logics (Holmes 2011; Okereke 2007; Sullivan 2013; Swyngedouw 2013). By adopting such discourses and endorsing biased institutional arrangements, these approaches to environmental justice risk depoliticising and disempowering their subjects. Where power imbalances are explicitly invoked, it is primarily through the lens of mainstream state-centric IR theory. As a general rule, scholarship on global environmental governance and global environmental politics more widely, fails to take account of inequalities in social power relations, within and between various levels of analysis (for example, Breitmeier et al. 2006; Mitchell et al. 2006). Within IR, power is operationalised as the ability to set rules (explicitly through formal channels but also implicitly through social interactions and defining the terms of debate), thereby making other actors do what they may not have done otherwise (Lukes 1974)

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.