Politics & International Relations

Pan Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a movement that advocates for the unity and solidarity of African people worldwide. It seeks to promote the political, social, and economic empowerment of African nations and people, and to combat colonialism, racism, and inequality. Pan-Africanism aims to foster a sense of shared identity and purpose among people of African descent, and to advance the interests of the African continent as a whole.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

Related key terms

1 of 4

Related key terms

1 of 3

10 Key excerpts on "Pan Africanism"

- Toyin Falola, Kwame Essien(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Pan-Africanism could be described as the movement for the unity of the Africans at home and abroad, within Africa and its diaspora. The diaspora, in this sense, includes the Western Diaspora in the Americas and Caribbean and the Eastern Diaspora in Arabia, North Africa, and other parts of the world where people of African descent are dispersed. For Charles Andrain, Pan-Africanism as an ideology was employed to signify “the underlying unity of the African continent and the vision of an independent, united Africa.” 1 From the foregoing, Pan-Africanism can be described as a sociocultural movement for Black consciousness. It is a philosophy that represents the aggregation of the historical, cultural, artistic, scientific, and ethical legacies of Africans from the past to the present with the aims of unifying Africans and protecting them as a people of collective identity struggling to evolve a more positive image of themselves. This is against the bastardization and degradation they suffered from historical experiences such as slavery and colonialism. This presupposes the general acceptance and use of Pan-Africanism as a social psyche, which emphasizes the rights and aspirations of Africans to self-determination and self-government as opposed to being subjects to colonialist authority in whatever form and/or objectives. The evolution of Pan-Africanism lies in the progressive development and amalgamation of various trajectories of African nationalism into the all-encompassing and all-involving (African) continental ideological sameness and political unity in the emerging and future eras. 2 It includes an avalanche of struggles and gradual attainment of the Black man’s (the African and the American Negro) right to self-assertion as a member of humanity and on an equal pedestal with other humans- eBook - ePub

Contemporary African Social and Political Philosophy

Trends, Debates and Challenges

- Albert Kasanda(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

5The pan-African movement

From race-based solidarity to political unity and beyond 1Introduction

Pan-Africanism originated in African diasporas in the late nineteenth century, and it spread to Africa in the middle of the twentieth century. Originally, this movement relied on the idea that black people all over the world constitute a single nation and that they have a common destiny. Therefore, they must unite to fight the discrimination and exploitation that they endure from white people (Outlaw 1996, 88). This thought developed through various theories, and it dominated the debate on black people’s destiny for almost a century. The awareness of new configurations and interdependencies2 taking shape in the world calls for a new consideration of pan-Africanist discourses. This call has become even more urgent due to the emergence of new and proliferating self-representations of black people through movements and theories such as Afropolitanism, cosmopolitanism, postcolonial theories, and globalization theories. Most critiques denounce the institutionalization and the ossification of traditional pan-Africanist discourse, which is viewed by some as disconnected from black people’s reality and aspirations.This chapter argues that pan-Africanism is neither outdated nor incongruous concerning contemporary black people’s realities because its fundamental purpose is not reducible to the defence of black people and black identity as an end in itself. This movement aims at supporting the struggle for human dignity and freedom which was embodied in categories of race and black people’s identity. Both these categories are strongly questioned today, as already mentioned, while the issue of human dignity is more than ever a burning debate that calls for the achievement of global justice and human rights. Therefore, this chapter suggests going beyond all kinds of Afrocentrism to instead define black people’s solidarity as part of the struggle against social inequalities and exclusion affecting human dignity regardless of African emancipation. - eBook - ePub

Back to Black

Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century

- Kehinde Andrews(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Zed Books(Publisher)

We have one destiny’. 4 Pan-Africanism was seen to represent the revolutionary overthrow of imperialism on the African continent. Pan-Africanism has become synonymous with movements such as Garveyism, which spread across the globe in the early twentieth century aiming to liberate ‘Africa for the Africans’. 5 Pan-Africanism, however, has a far more complicated history than being the revolutionary antidote to global racism. 6 In much of the literature on the topic the consensus is that, rather than representing a clear set of politics, the movement has ‘no founder, or particular set of political tenets’ and so ‘almost defies definition’. 7 So broad is the realm of the Pan-African that it has been defined as including ‘the liberation of Africa; the economic, social and cultural regeneration of Africa; and the promotion of African unity and of African influence in world affairs’. 8 These may all seem like worthwhile goals but Fanon warned that the main problem facing Africa in regard to independence was the lack of a coherent ideology. 9 It is not enough to want to liberate Africa, the question is how we go about doing so. In order to begin to distinguish between the varying forms, Shepperson marked the difference between capital and small ‘p’ Africanism. 10 Pan-Africanism with a capital letter marks the series of conferences and congresses that were started in London in 1900, while pan-Africanism captures the array of political movements that have put the unity of Africa and the Diaspora at their core. We must reject this orthodoxy of seeing Pan-Africanism as a wide range of different viewpoints and competing ideas. One of the most infuriating things about the way Black intellectual and political thought is understood is that we lump everything together as though it were one united history. The differences in how Africa is placed at the heart of Black politics are so diverse and contradictory it is an insult to think of them as being part of a whole - eBook - ePub

- Reiland Rabaka(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Ohadike, Pan-African Culture of Resistance: A History of Liberation Struggles in Africa and the Diaspora (Binghamton: Global Academic Publishing, 2002); George Padmore, ed., Colonial and Coloured Unity: A Programme of Action—History of the Pan-African Congress (London: Hammersmith, 1963); Thomas E. Smith, Emancipation Without Equality: Pan-African Activism and the Global Color-Line (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018); Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism (London: Longman, 1977); Ronald W. Walters, Pan-Africanism in the African Diaspora: An Analysis of Modern Afrocentric Political Movements (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000); Njoki Nathani Wane and Akena Francis Adyanga, eds., Historical and Contemporary Pan-Africanism and the Quest for African Renaissance (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019); Justin Williams, Pan-Africanism in Ghana: African Socialism, Neoliberalism, and Globalization (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2016); Rodney Worrell, Pan-Africanism in Barbados: An Analysis of the Activities of the Major 20th-century Pan-African Formations in Barbados (Washington, D.C.: New Academia Publishing, 2005); Josiah U. Young, Pan-African Theology: Providence and the Legacies of the Ancestors (Trenton: Africa World Press, 1992). 3 Peter Olisanwuche Esedebe, Pan-Africanism: The Idea and Movement, 1776–1991 (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1994), 7–8. 4 For further discussion of black internationalism, see Charisse Burden-Stelly and Gerald Horne’s brilliant elaborative essay in Part I of this volume. 5 For further discussion of black internationalism, as well as its relationship to Pan-Africanism, see Keisha N - Thierno Thiam, Gilbert Rochon(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

states , African unity became an imperative. The link between unity and independence could not, therefore, be any clearer.3 Conclusion

The essence of Pan -Africanism can be described more as a process toward the building of an identity than as a static and fixed symbol of Africanness . Thus, while the process which initiated the break had to originate in Africa , the process which would start the healing had undoubtedly to originate with the lost sons and daughters of Africa in the Caribbean and North America. After all, the story of Pan-Africanism is indeed the story of pioneers in the African Diaspora who, in their quest to find their own identity, found the Pan-African ideal. Pan-Africanism in this sense is deeply rooted and intrinsically linked to African-American and African-Caribbean identity politics . The story of Africans in Africa, in the same vein, will never be a distinct and separate story from that of Africans in the Western Hemisphere . Like two ends of a broken bone, the movement toward unity is a natural characteristic.It is also important to note that the process has been anything but an easy project. This was to be expected. What might not have been expected, however, is the depth and level of the conflict in conceptualizing unity in Africa between key drivers and intellectual architects of Pan -Africanism . The case of the two most influential theoreticians of African Unity in the Diaspora , notably Du Bois and Garvey, was mirrored by the profound ideological opposition between the two key theoreticians of African Unity in Africa: Nkrumah and Nyerere.Such opposition gave rise to indirect confrontations as well as direct verbal confrontations. Nowhere was this more obvious than during the 1964 Cairo Summit, where Nyerere argued that, beneath the veneer of African unity, Nkrumah was obsessed with how he would be viewed by posterity and that if that meant wrecking any chance of unity he would do it. Such opposition contributed a great deal to the paralysis of the project of continental unification during a time which represented arguably the best opportunity for Africa- Julian Kunnie(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Noted historical Black thinkers and leaders from the Caribbean, Africa, and the United States such as George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey were all vigorous Pan-Africanist advocates, the concept of Pan-Africanism originating with Henry Sylvester-Williams, a lawyer born in the West Indies who organized the first African conference in London in 1900. 1 Unfortunately, not many women were featured as prominent leaders within this historical movement, owing to the patriarchal contexts within which these figures functioned, even though recent womanist scholarship has demonstrated that Amy Jacques-Garvey, Garvey's last wife, did in fact exert considerable influence on the development of Pan-Africanist and Black nationalist thought. 2 A very positive development issuing from the Seventh Pan-African Congress in Kampala, Uganda, in April 1994, was the formation of the Pan-African Women's Liberation Organization, which had its first meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, in August 1995, and has begun to launch chapters throughout Africa and the African Diaspora. 3 One of the cardinal premises of Pan-Africanist philosophy is the mutualistic, reciprocal, and inclusive concern for Africa's descendants globally, an "African nationalism to replace the tribalism of the past: a concept of African loyalty wider than the 'nation' to transcend tribal and territorial boundaries." 4 George Padmore, a leading Pan-Africanist theoretician of the 1950s, viewed Pan-Africanism as offering an "ideological alternative to Communism on the one side and Tribalism on the other" and embracing "the federation of regional self-governing countries and their ultimate amalgamation into a United States of Africa." 5 "An injury to an African anywhere, is an injury to Africans everywhere" is one aphorism that derives from- eBook - ePub

African peace

Regional norms from the Organization of African Unity to the African Union

- Kathryn Nash(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

3 African leaders shared common experiences during the World Wars and in fighting for independence, and they also shared a common theoretical frame through pan-Africanism. As such, they shared a common belief in the need to ensure the total independence of the continent. However, they also had vastly different experiences in different colonial systems, and leaders differed on how to best achieve their goals. These commonalities and divergences shaped how individual leaders perceived the interests of the region and the most important tenets of pan-Africanism. Ultimately, they shaped the debates of the OAU founding conference and help to explain why certain norms were chosen over others.The influence of pan-AfricanismThe independence era leaders who created the OAU came from diverse backgrounds with varying educational and colonial experiences. However, there were common philosophical themes that emerged during the discussions that led to the OAU. Chief among these themes was pan-Africanism and what this concept meant in practice not just in theory for new African states. Pan-Africanism is complex idea that emerged over decades and continues to evolve today. In a very broad sense, pan-Africanism is about black race consciousness, self-determination of the black race, unity of the African people, economic development of Africa, and finding a dignified niche for Africans within the international system.4 However, within this encompassing philosophy there are deliberate points of vagueness. Unity, in particular, is a fluid concept and the degree of desired cohesiveness and cooperation has been continually debated.5 In a political sense, pan-Africanism manifested in African regional policies that valued cooperation among states over integration, demanded self-government for all Africans, condemned colonial and racial regimes that continued in some parts of Africa even after the initial wave of independence, and facilitated initiatives to forge a new role for Africa in world affairs.6In this chapter, I first trace the evolution of pan-Africanism and the events that influenced its evolution. From there, this book will demonstrate how the common experiences of the region and the diverging experiences of some independence African leaders shaped understandings of pan-Africanism. I will show the interaction between pan-Africanist ideas, the influence of key leaders and events, and regional interests that culminated in the OAU choosing non-intervention, state sovereignty, and territorial integrity norms. This conception of the creation of regional norms at the advent of the OAU will be shown to conform in many ways to Acharya’s theory of subsidiarity. African states did not simply adopt the prevailing norms of the international system. They adopted norms the vast majority of leaders believed would best defend Africa against domination and interference. OAU norms drew on international norms but were altered in ways that shored up African independent states whilst diminishing the legitimacy of white-minority regimes and outside interference, showing that regional institutions can craft norms to protect their regional interests and further their values. - eBook - ePub

Anarchism and the Black Revolution

The Definitive Edition

- Lorenzo Komboa Ervin(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Pluto Press(Publisher)

4

Pan-Africanism or Intercommunalism?

AFRICAN INTERCOMMUNALISM

The Anarchist ideals lead logically to internationalism or more precisely transnationalism, which means beyond the nation-state as an institution. Anarchists foresee a time when the nation-state will cease to have any positive value at all for most people and will in fact be junked by a social revolution. But that time is not yet here and until it is, we must organize for intercommunalism, or world relations between African/POC in America and other communities, tribes, neighborhoods and their revolutionary social movements around the world, instead of building unity with their governments and heads of state.The Black Panther Party first put forward the concept of intercommunalism in the 1960s and, although slightly different than what I am referring to with autonomous politics, the original Panther concept is very much a libertarian ideal at its core. Holding that as long as capitalist imperialism exists, there is no possibility of creating sovereign nations, intercommunalism seeks to unite oppressed Blacks in the United States with other oppressed peoples all over the world. All those fighting capitalist-colonialism and for a new world should be part of an international revolutionary liberation front.This is contrasted to “Pan-Africanism,” that is supposed to recognize all Africans as part of the Diaspora, but does not recognize the contradictions of neo-colonialism, so that corrupt dictators like Haile Selassie, Jomo Kenyatta and Tom Mboya are held up as legitimate leadership of the struggle, along with “revolutionary” governments and anti-colonial or independence movements. This was similar to the simplistic belief that all Blacks “are the same people” which dominated the 1960s during the Black Power phase. So any sell-out, CIA or FBI pig, politicians, or corrupt elements in our community were not exposed or eliminated by the masses just because they were Black. Some of these Black nationalists believe that any of these African politicians are champions of the freedom of African peoples, no matter how corrupt they are. This is dangerously naive and irresponsible. - eBook - ePub

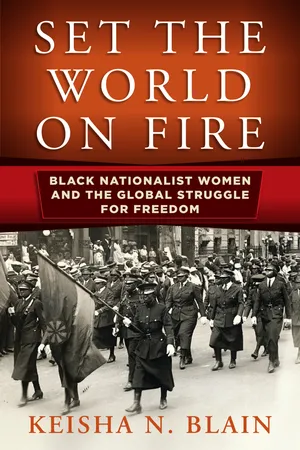

Set the World on Fire

Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

- Keisha N. Blain(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 5Pan-Africanism and Anticolonial Politics

WRITING IN 1944 to A. Balfour Linton, editor of The African newspaper, the Pan-Africanist leader Amy Jacques Garvey laid out a strategic plan for securing the political, social, and economic freedom of black men and women across the globe. “The Redemption of Africa,” she insisted, “is a solution for the ills of all Africans, those at home and those abroad, and all people of African descent, the world over.” “The nerve center is Africa,” she continued, “and unless, and until, this spinal column is put into working order, the limbs cannot function properly; for it is the nerve center—Africa—that we must get our motivating power.” “Strengthen that, and you automatically strengthen even the far-flung fingers and toes,” she added.1 Jacques Garvey’s statements, which came during a global economic and political crisis of World War II, reflected her unwavering commitment to anticolonialism and Pan-Africanism—the political belief that African peoples, on the continent and in the diaspora, share a common past and destiny.2 As colonial rule spread throughout Africa, Jacques Garvey emerged as part of a vanguard of black nationalist women leaders at the forefront of black liberatory movements. In the 1940s, she launched an international Pan-Africanist movement from her base in Jamaica, aimed at challenging global white supremacy and securing universal black liberation.As Jacques Garvey fought to eradicate the global color line from her base in Jamaica, a vast diasporic community of black women from all walks of life, many of them involved in black nationalist organizations, were also engaged in anticolonial and Pan-Africanist politics. Amid the sociopolitical upheavals of World War II, Amy Bailey, Ethel M. Collins, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Una Marson, and many other black women activists and intellectuals of the period challenged global white supremacy through various mediums, including journalism, media, and overseas travel. Recognizing that the challenges facing people of African descent in the United States or any other nation-state were deeply intertwined with the experiences of black people throughout the diaspora, these black nationalist women promoted a global black liberationist vision and added distinctive voices to discourses surrounding Pan-Africanism. Through an array of writings and speeches during the 1940s, they exercised their political agency, affirmed their humanity, and demanded equal recognition and participation in global civil society. - eBook - ePub

African Culture and Global Politics

Language, Philosophies, and Expressive Culture in Africa and the Diaspora

- Toyin Falola, Danielle Sanchez(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Ultimately, the purpose of this volume is to provide a greater understanding of some of the unique ways Africans participate in world politics, and, perhaps, the ways that African world-views and philosophies may provide an interesting way of examining international and domestic politics in the past, present, and future. African agency is at the forefront of this text and is a continuous thread throughout each of the contributors’ chapters. It is only through such a reclamation of African voices (especially those that are often heard in unlikely places) that one can understand the complexity of the African and diasporic experience. However, it is important to note that this volume is just a beginning. These are merely case studies or glimpses into a much larger phenomenon that deserves greater, in-depth attention. It is this volume’s goal to expand discussions of uniquely African insertions in global politics and inspire future works.***This volume is divided into three parts that center on the topic of the intersection of global politics and expressive culture in Africa and the African diaspora. The volume begins with Part I: African Philosophies and Philosophies for Africa. The chapters within this section primarily focus on culture and philosophy in Africa and the African diaspora and the ways in which philosophies for and from Africa shaped understandings of politics both inside and outside the African continent. This broad theme envelops a variety of chapters that include discussions of developmental ideologies for French colonialism in northern Africa; issues of assimilation and Islam in the colonization of Algeria; the importance of African philosophies in world politics and how uniquely African ideologies can help us reconsider the meaning of international politics; the political, cultural, and social implications of religious missions emerging from the African continent; the precarious position of Somalia and what can be learned from what has, perhaps, too quickly been labeled a “failed state”; and finally, the parallel evolution of civil rights and anti-apartheid movements in the United States and South Africa.The second part of the volume focuses on literature, language, rhetoric, and politics in Africa and the African diaspora. Linguistics, rhetoric, and expressive culture are immensely important, especially in world politics. Thus, this section seeks to address Africa’s unique position in both spoken word and written texts, and how these spaces served as forums for upholding African identities and ideologies, especially as Africans were participating in larger exchanges that extended beyond the continent of Africa. Therefore, Part II includes a variety of chapters that center on this topic and expand our understandings of expressive culture and politics through discussions of language issues in international forums, world memory and the role of African literary works, conflict resolution in African literature, and literary works on religion and political protest in the African diaspora. Such a wide array of chapters allows us to conceptualize the importance of rhetoric on both micro and macro levels when considering Africa’s role in international politics in addition to what these literary and rhetorical expressive devices mean for the creation of diasporic communities.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

Explore more topic indexes

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 6

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 4